Pediatric acute laryngitis is a condition that commonly occurs in children between 6 months and 3 years old, with higher incidence during winter and spring. Although the overall occurrence is low, the condition carries distinct characteristics, particularly its tendency to cause respiratory distress. The clinical manifestations in children differ from those in adults due to the loose submucosal tissues in the pediatric larynx, which are prone to swelling during inflammation. The smaller laryngeal cavity and glottis in children also increase the risk of laryngeal obstruction, leading to respiratory difficulty. Moreover, children's weaker cough strength and difficulty expelling secretions from the lower respiratory tract and larynx often result in more severe illness compared to adults. Untimely diagnosis and treatment can be life-threatening.

Etiology

Pediatric acute laryngitis is often secondary to common colds or other upper respiratory tract infections and may also accompany acute infectious diseases such as influenza, measles, and pertussis. Malnutrition, reduced immunity, allergic constitutions, or chronic upper respiratory diseases can act as inducing factors.

Clinical Manifestations

The onset of acute laryngitis in children is typically rapid, with primary symptoms including hoarseness, barking cough, inspiratory stridor, and inspiratory dyspnea. Since the condition often follows upper respiratory tract infections or acute infectious diseases, systemic symptoms such as fever and fatigue may also be present in addition to laryngeal symptoms.

Hoarseness is initially mild but progressively worsens as the condition advances. When inflammation extends to the subglottic region, barking cough develops. As subglottic mucosal edema worsens, inspiratory stridor occurs. In severe cases, inspiratory dyspnea may present along with nasal flaring and the presence of suprasternal, intercostal, and subcostal retractions (known as the "three-retraction sign"). Without timely intervention, symptoms can progress to pallor, cyanosis, altered consciousness, and ultimately respiratory and circulatory failure, resulting in death.

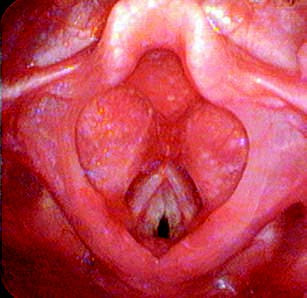

Flexible (electronic) nasopharyngolaryngoscopy reveals congested and swollen laryngeal mucosa. The vocal cords appear transformed from white to pink or red. In some cases, mucopurulent secretions or pseudomembranes are visible on the mucosal surface. Subglottic mucosal edema is observed protruding toward the midline.

Figure 1 Pediatric acute laryngitis

Diagnosis

The acute onset of the disease calls for immediate attention, as delays in diagnosis and treatment may threaten the child's life. Hoarseness and barking cough in a child should prompt suspicion of acute laryngitis. The presence of inspiratory stridor and dyspnea confirms the diagnosis.

Flexible (electronic) nasopharyngolaryngoscopy serves as a valuable diagnostic tool to clearly assess the condition of the vocal cords and subglottic region, allowing an accurate evaluation of inflammation and edema. Close monitoring of disease progression is essential in cases of vocal cord swelling or significant subglottic edema/narrowing that poses a risk of asphyxiation.

Differential Diagnosis

Tracheal or Bronchial Foreign Bodies

A clear history of foreign body aspiration, accompanied by severe coughing and respiratory distress, suggests this condition. Chest auscultation, X-rays, and bronchoscopy assist in differentiation. For patients with hoarseness, flexible (electronic) nasopharyngolaryngoscopy is required to rule out acute laryngeal obstruction caused by a foreign body.

Laryngeal Diphtheria

Although rare today, the presence of grayish-white pseudomembranes on examination of the pharynx or larynx in a child with clinical features of acute laryngitis warrants differentiation from laryngeal diphtheria. The latter can be confirmed by identifying Corynebacterium diphtheriae in smears or cultures of the pseudomembrane.

Laryngospasm

This condition presents with a sudden onset of inspiratory stridor and dyspnea but without hoarseness or barking cough. Laryngospasm episodes are typically brief, with full recovery once the spasm resolves.

Fungal Laryngitis

This condition is often associated with a history of recurrent upper respiratory infections or prolonged antibiotic use. Thrush in the oral cavity is commonly seen, and hoarseness persists for an extended period with little improvement despite symptomatic treatment. Flexible (electronic) nasopharyngolaryngoscopy reveals white pseudomembranous lesions on the laryngeal and vocal cord surfaces.

Congenital Laryngeal Anomalies

This condition is rare and often presents with stridor soon after birth, which worsens with respiratory infections. Flexible (electronic) nasopharyngolaryngoscopy helps exclude congenital anomalies. Patients with congenital subglottic stenosis require diagnostic confirmation through laryngoscopy under general anesthesia.

Treatment

This condition poses a potential threat to the child's life. Immediate and effective intervention to relieve respiratory distress is essential once the diagnosis of pediatric acute laryngitis is established.

Symptomatic Treatment

Nebulization, oxygen supplementation, antispasmodic medication, and expectorants are used to alleviate laryngeal edema symptoms. For children with dry crusts or thick sputum in the subglottic region, increased frequency of nebulization assists in sputum clearance. Corticosteroids, such as oral prednisone [1–2 mg/(kg·d)], may be administered.

Etiological Treatment

Antibiotics, such as penicillins or cephalosporins, effectively control bacterial infections. Early administration of corticosteroids can reduce and resolve laryngeal mucosal edema. Simultaneous use of adequate antibiotics is necessary to control infections.

In cases of severe respiratory distress where corticosteroids, antibiotics, and nebulization fail to improve symptoms, tracheotomy is performed based on the degree of dyspnea. For grade I respiratory distress, anti-inflammatory and anti-edema treatment is prioritized. Grade II respiratory distress requires active medical treatment under continuous ECG monitoring, while preparations for tracheotomy are made. Grade III and IV respiratory distress necessitate immediate tracheotomy.

Supportive Therapy

Fluid replacement and maintenance of water-electrolyte balance are required. Keeping the child calm and minimizing crying helps reduce physical exertion and alleviate respiratory distress.