Congenital laryngomalacia is a condition characterized by the collapse of supraglottic tissue during inspiration, leading to inspiratory stridor and symptoms of upper airway obstruction, such as choking, aspiration, and swallowing difficulties. It primarily manifests as inspiratory stridor in infants shortly after birth and may be accompanied by retraction signs. Stridor is a symptom caused by laryngeal obstruction, rather than an independent disease.

Laryngomalacia is the most common congenital laryngeal anomaly and is primarily marked by the prolapse of supraglottic tissue into the airway during inspiration, causing inspiratory stridor and upper airway obstruction.

Etiology

The exact cause of laryngomalacia remains unclear. Current theories suggest that it is associated with factors such as anatomical structure, neural innervation and function, as well as inflammatory processes.

Clinical Manifestations

The typical clinical presentation includes intermittent inspiratory stridor, which worsens during feeding, physical activity, crying, or upper respiratory tract infections. Retraction signs may also occur, though the infant's cry remains non-hoarse. Feeding difficulties represent another important feature of this condition and can result in growth and developmental delays.

Diagnosis

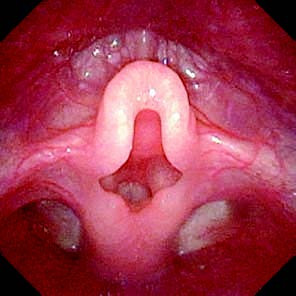

The diagnosis of laryngomalacia relies on the timing of symptom onset, the presence of characteristic symptoms, and laryngeal examination findings that reveal distinctive anatomical abnormalities. Fiberoptic or electronic nasopharyngolaryngoscopy typically shows shortened aryepiglottic fold membranes, as well as the collapse of arytenoid mucosa and epiglottis into the laryngeal inlet during inspiration.

Laryngoscopy findings are used to classify laryngomalacia into three subtypes:

- Type I: Prolapse of arytenoid mucosa.

- Type II: Shortening of the aryepiglottic folds.

- Type III: Posterior displacement of the epiglottis, with inward folding and collapse that obstructs the glottis during inspiration.

Mixed types involving both Type I and Type II are more common in clinical practice, while Type III laryngomalacia is relatively rare.

Figure 1 Mixed laryngomalacia

Treatment

No specific treatment may be required when the infant demonstrates normal growth and development.

Conservative Treatment

Improving balanced nutrition is a key approach. In some infants, laryngomalacia is associated with gastroesophageal reflux, and measures to prevent gastroesophageal reflux should be undertaken to potentially alleviate symptoms.

Surgical Treatment

Mild cases may gradually resolve spontaneously by the age of two.

For severe cases, surgical intervention is necessary, particularly in those experiencing respiratory distress, poor weight gain, growth and developmental delays, or life-threatening airway obstruction. Indications for surgery include inability to feed orally, difficulty gaining weight, growth stagnation, delayed neurodevelopment, life-threatening airway events, pulmonary hypertension or cor pulmonale, hypoxemia, or hypercapnia. The primary surgical approach is supraglottoplasty.