Etiology

The development of nasopharyngeal carcinoma (NPC) is associated with a combination of genetic, viral, and environmental factors.

Genetic Factors

NPC demonstrates racial and familial clustering. Certain human leukocyte antigen (HLA)-related genetic factors are closely linked to the occurrence and progression of NPC.

Epstein-Barr Virus (EBV)

In NPC patients, high titers of anti-EBV antibodies are present, and antibody levels fluctuate with disease progression, highlighting EBV's significant role in NPC development. However, EBV infection is widespread globally, while NPC shows clear geographic localization. This suggests that EBV infection alone is not the sole causative factor for NPC.

Other Factors

Exposure to heavy metals such as cadmium and nickel may promote NPC development. Vitamin deficiencies and hormonal imbalances may also alter the sensitivity of mucosal tissues to carcinogens.

Pathology

NPC most frequently occurs on the roof and lateral walls of the nasopharynx. Lesions can appear as nodular, ulcerative, or submucosal infiltrative types. Pathological classifications include keratinizing squamous cell carcinoma, non-keratinizing carcinoma (differentiated and undifferentiated types), and basaloid squamous cell carcinoma, with non-keratinizing carcinoma being the most common.

Clinical Manifestations

Because the anatomical position of the nasopharynx is concealed, early symptoms of NPC are nonspecific, leading to delayed diagnoses in clinical practice. Common symptoms include:

Nasal Symptoms

Early signs include blood-streaked mucus when sniffing or blowing the nose, occurring intermittently and often overlooked. Enlargement of the tumor can block the posterior nasal foramen, causing nasal obstruction that begins unilaterally and later progresses to bilateral obstruction.

Ear Symptoms

Tumors in the fossa of Rosenmüller may compress or obstruct the opening of the Eustachian tube early on, leading to symptoms such as tinnitus, aural fullness, and hearing loss on the affected side. These symptoms may result in serous otitis media, with many cases of NPC being discovered during consultations for ear-related complaints.

Cervical Lymph Node Enlargement

This accounts for the initial symptom in approximately 60% of cases. Metastases are most commonly observed in the upper deep cervical lymph nodes, initially on one side and subsequently bilaterally.

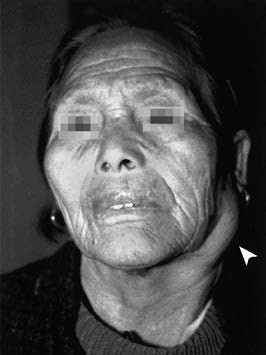

Figure 1 Enlarged upper deep cervical lymph node on the left side in a patient with nasopharyngeal carcinoma

Cranial Nerve Symptoms

Tumors in the fossa of Rosenmüller frequently invade the base of the skull, damaging cranial nerves through the foramen lacerum and carotid canal, with the petrous apex often affected. This leads to damage of the cranial nerves V and VI, potentially involving cranial nerves II, III, and IV, manifesting as symptoms such as unilateral headache, facial numbness, diplopia, ptosis, and vision loss. Tumors may also invade the parapharyngeal space directly or compress cranial nerves IX, X, and XII via metastatic lymph nodes, causing symptoms such as soft palate paralysis, dysphagia with choking, hoarseness, and tongue deviation.

Distant Metastasis

Advanced NPC may display distant metastases, commonly affecting the bones, lungs, and liver.

Examinations

Indirect Nasopharyngoscopy

The nasopharynx may reveal small nodular or granulomatous elevations with a rough and irregular surface prone to bleeding. In some cases, submucosal elevations with a smooth surface are observed. Early lesions appear nonspecific, potentially displaying mucosal congestion, disorganized vascular patterns, or fullness in one fossa of Rosenmüller. These subtle abnormalities require close attention to avoid misdiagnosis.

Cervical Palpation

Firm, poorly mobile or immobile, painless enlarged lymph nodes may be detected in the upper deep cervical region.

Fiberoptic/Electronic Nasopharyngoscopy or Nasopharyngeal Endoscopy

These provide a more direct view compared to indirect nasopharyngoscopy. The application of narrow-band imaging (NBI) endoscopy enhances detection of small early lesions.

Figure 2 Neoplasm located in the right nasopharyngeal region

Figure 3 The short arrow indicating the nasopharyngeal neoplasm observed in nasal endoscopy; the long arrow indicating the pharyngeal orifice of the Eustachian tube.

EBV Serology

Serological testing for EBV serves as an auxiliary diagnostic tool for NPC. Currently available tests include detection of anti-EBV capsid antigen (EBV VCA), anti-EBV early antigen (EBV EA), anti-EBV nuclear antigen (EBV NA), and EBV-specific DNAse antibodies.

Imaging Studies

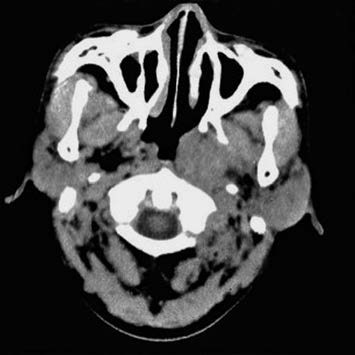

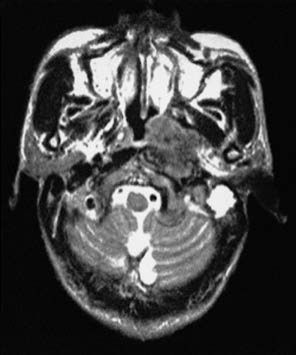

CT and MRI facilitate assessment of tumor extent and the degree of skull base involvement.

Figure 4 CT scan showing mucosal thickening and fullness in the left nasopharyngeal region

Figure 5 MRI scan showing a neoplasm in the left nasopharyngeal region

Diagnosis

The clinical presentation of nasopharyngeal carcinoma (NPC) is highly variable, making it prone to missed or incorrect diagnoses. Pathological diagnosis serves as the gold standard. Screening with fiberoptic nasopharyngoscopy or nasopharyngeal endoscopy plays an essential role. If a patient presents with unexplained symptoms such as blood-streaked mucus during nasal discharge or postnasal drip, unilateral nasal obstruction, tinnitus, aural fullness, hearing loss, headache, diplopia, or upper deep cervical lymphadenopathy, fiberoptic nasopharyngoscopy or nasopharyngeal endoscopy should be conducted promptly, along with a biopsy of the nasopharyngeal region. Additionally, serological testing for Epstein-Barr virus (EBV) and imaging studies may also be performed to confirm the diagnosis.

It must be noted that the primary lesion of NPC can sometimes invade intracranially without altering the appearance of the nasopharyngeal mucosa. A negative initial biopsy or normal nasopharyngeal mucosa appearance cannot entirely rule out NPC. Close follow-up is essential for suspected cases, with repeated biopsies when necessary. In early stages, cervical lymph node metastasis may occur, which often leads to NPC being misdiagnosed as lymph node tuberculosis or cervical lymphoma.

Treatment

Radiotherapy-based comprehensive treatment is the primary approach for NPC. Endoscopic surgery for early-stage cases remains under exploration. Surgical interventions may be considered in certain situations:

- Residual lesions, recurrence in the nasopharyngeal region, or skull base necrosis following radiotherapy.

- Persistent metastatic lesions in the retropharyngeal or cervical lymph nodes after radiotherapy, for which neck dissection may be performed.

- Recurrent tumors after radiotherapy, where treatment may involve endoscopic surgery or supplementary comprehensive treatment following re-irradiation.

The overall 5-year survival rate for NPC is approximately 74%–89%, with local recurrence and distant metastasis being the primary causes of mortality.