Osteoma

Osteomas are commonly found in young males and are relatively rare in females. They most frequently occur in the frontal sinus, followed by the ethmoid sinus, with the maxillary and sphenoid sinuses being less commonly affected.

Etiology

The exact cause of osteomas remains unclear. However, the possible mechanisms include the following:

Osteomas may arise from embryonic remnants of the periosteum, which is why they are frequently found at the junction of the frontal bone (intramembranous ossification) and the ethmoid bone (endochondral ossification).

Trauma and chronic inflammation, especially trauma, can lead to hyperplasia of the periosteum lining the paranasal sinuses or their bony walls. Approximately 50% of osteomas are associated with a history of frontal trauma. In some cases, single or multiple osteomas are associated with chronic sinusitis, suggesting that chronic inflammatory stimulation may be a contributing factor.

Pathology

Osteomas are well-differentiated, slow-growing tumors of variable size. They may be sessile or pedunculated, appearing round or oval with smooth, normal mucosal surfaces. Osteomas originating in the paranasal sinuses can grow large enough to compress the sinus walls, leading to facial swelling or protrusion into the nasal cavity, orbit, or intracranial space. This may result in facial deformities, dysfunction of affected organs, or complications such as brain compression in severe cases. Histologically, osteomas are classified into three types:

- Compact type (hard or ivory type): Dense and hard, often pedunculated, slow-growing, and commonly found in the frontal sinus.

- Cancellous type (soft or spongy type): Softer in texture and formed by ossified fibrous tissue. These osteomas have a broad base, tend to be larger, and grow more rapidly. In some cases, central liquefaction may lead to cyst formation, surrounded by a harder bony shell. This type is commonly seen in the ethmoid sinus.

- Mixed type: The most common type, characterized by a dense exterior and a spongy interior, typically occurring in the frontal and ethmoid sinuses.

Clinical Manifestations

Small osteomas are often asymptomatic and are incidentally discovered during X-ray or CT imaging of the sinuses or skull. Large frontal sinus osteomas may lead to nasal and facial deformities, frontal headaches, and sensory abnormalities.

Figure 1 Osteoma of the ethmoid sinus

Diagnosis

X-ray or CT imaging of the sinuses reveals round or oval areas of high bone density, which help determine the location, size, extent, and attachment site of the osteoma. Clinically, osteomas should be differentiated from exostosis, which is more commonly found in the maxillary sinus and results from excessive bone overgrowth that sometimes causes swelling and facial deformity.

Treatment

Surgical resection is considered the standard approach for treating osteomas. Small, asymptomatic osteomas that do not cause facial deformities are generally left untreated but require regular follow-up for observation. Larger osteomas that cause compressive symptoms, intracranial extension, or intracranial complications require surgical removal.

Surgical approaches can be classified into four main categories:

- External frontal sinusotomy.

- Lateral rhinotomy.

- Craniofacial approaches, including frontal bone remodelling with bicoronal incisions.

- Endonasal endoscopic surgery.

Small osteomas confined primarily to the paranasal sinuses can be removed endoscopically through a nasal approach, with care taken to preserve and protect the sinus mucosa and dura. For osteomas with intracranial involvement, a craniofacial resection via a bicoronal incision is required for complete removal.

Chondroma

Chondroma of the nose and paranasal sinuses is a rare occurrence. It most commonly arises in the ethmoid sinus, followed by the maxillary and sphenoid sinuses. Primary chondromas originating in the nasal cavity, nasal septum, or nasal wing cartilage are even less common. They predominantly affect males, with the peak age of incidence between 10 and 30 years, and often cease growing after puberty.

Etiology

The exact cause of chondromas remains unclear. They are thought to be associated with factors such as trauma, developmental defects, chronic inflammation, and conditions like rickets.

Pathology

Chondromas typically have a pale blue, yellow, or light blue appearance, with a smooth surface. They present as spherical, broad-based masses and may also exhibit nodular or lobulated forms. Most chondromas are encapsulated, well-demarcated, and elastic with cartilage-like hardness. When located in the paranasal sinuses, they can fill the sinus cavity and invade or destroy the bony walls, potentially extending into the orbit or oral cavity. Larger tumors may exhibit mucinous changes, cystic degeneration, softening, necrosis, calcification, or ossification in their central regions.

According to their site of origin, chondromas can be classified into two types:

- Enchondral (Central): These arise within bone tissue that does not normally contain cartilage. They can occur as solitary or multiple lesions and are found in locations such as the ethmoid bone, maxilla, sphenoid bone, nasal septum, and lateral nasal wall.

- Perichondral (Peripheral): These develop around cartilage and are commonly found in the anterior nasal septum, external auditory canal, and laryngeal cartilage.

Chondromas grow slowly, and although they are histologically benign, they possess significant growth potential. Over time, their gradual expansion can compress and erode adjacent soft tissues and bone, as well as invade neighboring structures, producing symptoms similar to those of malignant tumors.

Clinical Manifestations

Symptoms vary depending on the tumor's size, extent, and location. Common presentations include unilateral progressive nasal obstruction, excessive nasal discharge, a reduction in the sense of smell, dizziness, and headaches. Tumors that grow larger and invade the paranasal sinuses, orbit, or oral cavity may result in facial deformities, displacement of the eyeball, diplopia, and epiphora.

Nasal endoscopy typically reveals a smooth-surfaced mass with a broad base, normal mucosal covering, and a tendency to bleed easily upon contact.

Diagnosis

X-ray imaging or CT scanning of the paranasal sinuses provides clear visualization of the tumor boundaries and its invasion into surrounding structures. These imaging studies may show central radiolucency, while calcification or ossification within the tumor appears as characteristic spotty opacities. Histopathological examination confirms the diagnosis. Differential diagnoses include osteoma, localized overgrowth of cartilage in the nasal septum, and ectopic chondroid islands in the nasopharyngeal mucosa. Distinguishing chondroma from chondrosarcoma can occasionally be challenging.

Treatment

Surgical excision is the primary treatment modality, as chondromas are not responsive to radiotherapy. Given their clinical characteristics resembling malignant tumors, their tendency to recur after surgery, and their potential for malignant transformation into chondrosarcoma, surgery is recommended as early as possible. The surgical resection should be thorough. For well-localized lesions, endonasal endoscopic surgery is preferred. For more extensive lesions, an external approach is often required. Long-term postoperative follow-up and observation are necessary.

Neurilemmoma and Neurofibroma

Neurilemmoma (schwannoma) and neurofibroma are common peripheral nerve tumors. They usually arise from the sensory nerves or the sensory component of mixed nerves, but may also originate from the sympathetic or parasympathetic nerves. Approximately 90% of neurilemmomas are solitary, while about 10% are multiple. When multiple neurofibromas are accompanied by subcutaneous nodules throughout the body and skin pigmentation, the condition is referred to as neurofibromatosis (von Recklinghausen's disease). Nasal neurilemmomas are most commonly seen in the nasal septum, maxillary sinus, and ethmoid sinus, though they can also occur in the nasal root, nasal wing, nasal tip, columella, nasal vestibule, and cribriform plate, among other locations.

Pathology

Neurilemmomas, also known as Schwannomas, originate from Schwann cells in the nerve sheath. These tumors characteristically have a smooth surface, are encapsulated, grayish-white in color, and vary in consistency. They are usually round or oval and may be pedunculated, with the associated nerve located on the surface of the tumor. In contrast, neurofibromas lack a capsule and tend to have a lobulated structure. The originating nerve often passes through the center of the tumor, resulting in more pronounced nerve compression symptoms.

Clinical Features

Neurilemmomas and neurofibromas are slow-growing tumors with clinical courses that can span more than a decade. In the early stages, they are often asymptomatic. Over time, as the tumor enlarges, symptoms vary depending on its location and size. Lesions of the external nose might produce an elephantiasis-like appearance, while tumors in the nasal cavity or paranasal sinuses may cause nasal obstruction, minor epistaxis, localized deformity, and headaches. Large tumors can involve multiple paranasal sinuses and, in severe cases, erode the cribriform plate to extend intracranially, producing symptoms of brain compression.

On examination, the tumors typically appear grayish-white, smooth-surfaced, and moderately firm. Neurofibromas, due to their lack of a distinct capsule, may present with pain on palpation, touch, or tension.

Diagnosis

The diagnosis is based on the patient's history, clinical manifestations, examination findings, and particularly imaging studies. Magnetic resonance imaging (MRI) is the preferred imaging modality, as it delineates the tumor's extent and its relationship with adjacent structures. The definitive diagnosis is confirmed through histopathological examination.

Treatment

Surgery is the only treatment option. Indications for surgery are determined by symptoms such as functional impairment (e.g., nasal obstruction) or deformities involving the nose or eyes.

Smaller tumors may be monitored with regular follow-up. For larger tumors involving the paranasal sinuses, orbit, pterygopalatine fossa, or infratemporal fossa, the surgical approach and incision design are tailored to the tumor's location. Neurilemmomas, due to their encapsulated nature and minimal adhesion to surrounding tissues, can often be completely excised with preservation of the origin nerve, resulting in a favorable prognosis. In contrast, neurofibromas are unencapsulated and more challenging to remove completely. As a result, residual nerve dysfunction is common postoperatively, and recurrence is more likely. Additionally, benign neurofibromas have a higher propensity than neurilemmomas to undergo malignant transformation, with a reported malignancy rate of 3%–12%.

Hemangioma

Hemangioma is one of the benign vascular tumors and is a common occurrence in the nose and paranasal sinuses. This condition can develop at any age but is more frequently observed in young and middle-aged individuals, with a recent trend of increasing incidence in children. Hemangiomas of the nose and paranasal sinuses can be classified into capillary hemangiomas and cavernous hemangiomas. Approximately 80% of cases are capillary hemangiomas, which are commonly located in the nasal septum, while cavernous hemangiomas typically arise in the inferior turbinate or within the maxillary sinus.

Etiology

The cause of hemangioma is unknown. It may be associated with residual embryonic tissue, trauma, or endocrine dysfunction.

Pathology

Capillary hemangiomas in the nasal cavity are composed of numerous well-differentiated capillaries. These tumors are generally small, pedunculated, brightly red or dark red, round or oval in shape, with a soft, elastic, mulberry-like consistency that bleeds easily. Cavernous hemangiomas consist of blood-filled sinusoids of varying sizes. These tumors tend to be larger and often arise at the natural opening of the maxillary sinus, where they may protrude into the middle meatus in the form of a bleeding polyp. As a cavernous hemangioma grows in the nasal sinuses, it may compress the sinus walls, destroy the surrounding bone, and invade adjacent structures. Tumor expansion toward the exterior can lead to facial deformities, ocular dislocation, diplopia, and headaches.

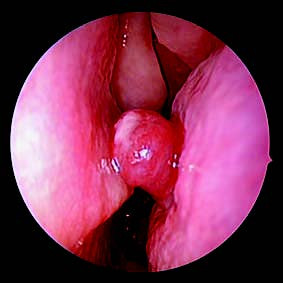

Figure 2 Hemangioma of the nasal septum

Clinical Manifestations

Recurrent episodes of epistaxis occur, with the amount of bleeding varying each time. Gradual nasal obstruction is noted on the affected side of the nasal cavity. Larger tumors may compress and cause deviation of the nasal septum to the opposite side, resulting in bilateral nasal obstruction. Secondary infections may produce a foul odor from the nasal cavity. Extensive bleeding can lead to secondary anemia; in severe cases, shock can occur, though death is rare. Posterior tumor extension into the nasopharynx might result in eustachian tube obstruction, presenting as tinnitus and hearing loss. Larger tumors can cause facial swelling, ocular displacement, and other symptoms that mimic clinical manifestations of malignant nasal or sinus tumors.

Diagnosis

The diagnosis is based on clinical presentation, nasal examination, and imaging studies. Diagnostic puncture is generally not recommended. CT or MRI imaging may reveal a unilateral soft tissue mass within the nasal cavity or sinuses, often accompanied by localized bone resorption with medial displacement of the lateral nasal wall. Contrast-enhanced imaging shows significant enhancement of the lesion. Cavernous hemangiomas may expand the affected maxillary sinus, leading to bone absorption and associated facial deformities, potentially creating diagnostic confusion with maxillary sinus malignancies. Maxillary sinus exploration may sometimes be necessary for a definitive diagnosis. Differentiating a hemorrhagic, necrotic polyp in the maxillary sinus from a hemangioma can be challenging, as histopathological examination may occasionally fail to clearly distinguish between the two.

Treatment

Surgical excision is the primary treatment. For small hemangiomas located at the anterior-inferior aspect of the nasal septum, excision should include the tumor and its base mucosa, followed by wound site electrocoagulation to prevent recurrence.

For tumors located in the sinuses, particularly the maxillary sinus, the selection of surgical methods depends on the size and location of the tumor. Endoscopic sinus surgery can be utilized to open the maxillary sinus for complete tumor removal. Other approaches include the Caldwell-Luc procedure, Denker's access, or lateral rhinotomy. For larger tumors, preoperative measures such as low-dose radiotherapy or injection of sclerosing agents may be used to reduce intraoperative bleeding. Selective maxillary artery embolization performed before surgery is also effective in minimizing intraoperative blood loss.

Meningioma

Meningioma, also known as arachnoid endothelial tumor, originates from arachnoid cells in the nerve sheath and is one of the more common benign intracranial tumors. Meningiomas localized to the nasal region are relatively rare. Most cases originate intracranially and, in rare instances, extend downward into the nasal cavity and paranasal sinuses. Primary extracranial meningiomas are uncommon and are more often found in locations such as the orbit, cranial bones, scalp, middle ear, and neck. Primary meningiomas of the nasal cavity and paranasal sinuses are extremely rare and may occur in sites such as the maxillary sinus, frontal sinus, ethmoid sinus, olfactory groove, or nasopharynx. The etiology remains unclear.

Pathology

Meningiomas can be classified based on histological morphology into the following types:

- Meningothelial Meningioma: Characterized by large tumor cells with clear boundaries, abundant and eosinophilic granular cytoplasm, arranged in nest-like patterns within stroma enriched with blood vessels.

- Psammomatous Meningioma: Spindle-shaped cells arranged in a whorled pattern, with central hyaline degeneration. The hyaline material may become calcified, forming concentric psammoma bodies.

- Fibroblastic Meningioma: Originating in the fibrocollagenous structures of the arachnoid.

- Angiomatous Meningioma: Tumor appearing spongy, with hypertrophic cells lining the abundant vasculature.

- Osteochondromatous Meningioma: Similar in structure to meningothelial meningioma.

Clinical Presentation

Meningiomas exhibit slow progression, often remaining asymptomatic for 2–3 years. As the tumor enlarges, compression of surrounding tissues leads to symptoms such as nasal obstruction, rhinorrhea, epistaxis, anosmia, and headaches. Meningiomas of the paranasal sinuses may erode the bony walls, extending into the nasal cavity, adjacent sinuses, and orbit, causing facial deformities, ocular displacement, and vision impairment.

Olfactory groove meningiomas can invade the cribriform plate and extend into the anterior cranial fossa, exerting pressure on the frontal lobe. These tumors are typically round, smooth, firm with a rubbery texture, and whitish or grayish in color. They resemble polyps, are encapsulated, and are relatively easy to dissect.

Diagnosis

The diagnosis is suggested based on the patient’s history, symptoms, and physical examination findings. Imaging studies, including CT and MRI with and without contrast enhancement, are routinely employed. Definitive diagnosis relies on pathological examination.

Treatment

Meningiomas show limited sensitivity to radiation therapy. The primary treatment approach involves surgical excision, as incomplete removal carries a high risk of recurrence. For tumors confined to the nasal cavity or paranasal sinuses, endoscopic resection or lateral rhinotomy can be used. For cases where the tumor invades the anterior cranial base or extends from cranial base meningiomas into the nasal cavity and paranasal sinuses, a combined craniofacial approach may be required to address both intracranial and nasal/paranasal components.

Inverted Papilloma

Papilloma is a common benign tumor of the nasal cavity and sinuses, pathologically categorized into exophytic papilloma and inverted papilloma. Inverted papilloma of the nasal cavity and sinuses is prone to postoperative recurrence. Multiple surgeries and advanced age are associated with a higher risk of malignant transformation, with a malignant transformation rate of 7%. This condition is more common in males aged 50–60 years, with a male-to-female ratio of 3:1.

Etiology

The cause of inverted papilloma remains unclear. Research suggests a possible association with human papillomavirus (HPV) infection. The tumor exhibits local invasive behavior, tissue destruction, and a tendency for recurrence and malignancy, characteristics consistent with a true borderline or intermediate epithelial tumor.

Pathology

Inverted papillomas of the nasal cavity and sinuses commonly originate on the lateral wall of the nasal cavity, although they can also arise from the nasal septum, turbinates, or various sinuses. However, in most cases, the tumor extends from the nasal cavity into the sinuses, with primary sinus involvement being rare. Inverted papillomas exhibit distinct local invasiveness, making it challenging to determine the primary site when the tumor is widely invasive.

Inverted papillomas are generally large, soft, reddish, often multifocal, and grow diffusely. They appear lobulated or papilliform, with pedunculated or broad-based attachments. The tumor epithelium predominantly consists of transitional and columnar cells that grow inward into the stroma in a finger-like pattern, which gives this tumor its name. During clinical biopsy, superficial tissue often resembles a polyp, while the deeper tissue reveals the underlying inverted papilloma.

Clinical Manifestations

This condition typically presents unilaterally, with persistent nasal obstruction on one side that progressively worsens. Symptoms may include purulent nasal discharge, occasional blood-streaked mucus, or recurrent epistaxis. Some patients may also experience headaches or olfactory disturbances. The symptoms and signs vary depending on the size and location of the tumor. Tumor growth often causes impaired drainage of the nasal cavity and sinuses. Additionally, increased tumor size can compress nasal and sinus venous or lymphatic return, frequently leading to concurrent sinusitis and nasal polyps. Consequently, many patients undergo repeated surgeries for presumed "nasal polyps." On examination, the tumor appears polypoid or lobular, ranging in size and consistency, pink to grayish-red in color, with an irregular surface that bleeds easily upon touch.

Diagnosis

The diagnosis is relatively straightforward and relies on the patient's history and clinical findings. On imaging studies, X-rays may show reduced translucency of the affected sinus, sinus cavity enlargement, and, in some cases, bony destruction. CT scans of the paranasal sinuses assist in diagnosis, revealing unilateral soft tissue density in the sinus with possible bony destruction of the lateral nasal wall and indistinct sinus boundaries. The bone at the tumor’s origin may show hyperostosis. MRI provides greater clarity in determining tumor origin and extent. Enhanced T1-weighted imaging may reveal the characteristic "cerebriform pattern." Definitive diagnosis requires histopathological examination. Routine histopathology is recommended for any nasal or sinus "polyps," particularly unilateral ones, to prevent missed diagnoses.

Figure 3 MRI image of inverted papilloma in the nasal cavity and paranasal sinuses

Treatment

The primary treatment goal is complete surgical excision of the tumor. Common surgical methods include endoscopic sinus surgery, lateral rhinotomy, or a sublabial approach. Endoscopic tumor resection is the preferred choice. This entails full exposure of the tumor's base and complete removal of the tumor. For extensive tumors involving adjacent structures outside the sinuses or suspected malignancies, the choice of surgical method depends on the tumor's extent. Options include lateral rhinotomy or a craniofacial approach. Follow-up is critical and should include endoscopic examinations and imaging studies to allow for early detection and management of recurrent tumors. Radiotherapy is generally not recommended due to the potential for inducing malignant transformation.