Epistaxis, commonly known as a nosebleed, is a frequent clinical symptom that may result from nasal or sinus diseases, as well as certain systemic diseases. The former is more common. Bleeding may occur unilaterally or bilaterally, and it can manifest as recurrent intermittent bleeding or continuous bleeding.

In mild cases, blood may only appear in nasal discharge or in blood-stained mucus during backward suction. In severe cases, blood loss can exceed several hundred milliliters. A single episode of massive bleeding may lead to shock, while repeated small-volume bleeding over time can cause anemia. Most nosebleeds stop spontaneously or can be controlled by pinching the nasal ala. The bleeding site is often located in the anterior-inferior part of the nasal septum, known as the bleeding-prone area (Little's arterial plexus or Kiesselbach's venous plexus). In children and adolescents, nosebleeds commonly originate from this area. In middle-aged and elderly patients, bleeding frequently occurs in the posterior segment of the nasal cavity, such as Woodruff's nasopharyngeal venous plexus in the inferior meatus, or from arteries in the posterior part of the nasal septum (90% from the sphenopalatine artery). Bleeding from this region tends to be severe and difficult to control.

Etiology

Causes can be divided into local and systemic factors.

Local Causes

Trauma

Internal Nasal Trauma

Trauma to mucosal blood vessels caused by nose-picking, forceful nose blowing, vigorous sneezing, or improper use of intranasal medications can damage blood vessels. Nasal or sinus surgeries and nasal intubation can damage blood vessels or mucosa, and insufficient attention or improper management may result in nosebleeds.

External Nasal Trauma

Fractures of the nasal bone, septum, or sinus, as well as sudden changes in sinus pressure, may damage local blood vessels or mucosa. Severe nasal and sinus trauma may be accompanied by fractures of the anterior or middle skull base. Injury to the anterior ethmoidal artery often causes significant bleeding, while injury to the internal carotid artery poses a life-threatening risk.

Nasal Foreign Body

Nasal foreign bodies, frequently seen in children, often result in unilateral nasal bleeding or blood-stained nasal discharge.

Inflammation

Specific or nonspecific inflammation of the nasal cavity and sinuses can damage capillaries in the nasal mucosa, usually causing minor bleeding.

Tumors

Benign vascular tumors, such as nasal hemangiomas or juvenile nasopharyngeal angiofibromas, often lead to pronounced nosebleeds. Malignant tumors of the nasal cavity, sinuses, and nasopharynx may cause minor bleeding during their early stages, typically presenting as blood-streaked mucus or bloody nasal discharge that recurs intermittently. In advanced cases, destruction of large blood vessels can result in significant hemorrhage.

Other Causes

Nasal Septum Conditions

Common causes of epistaxis include a deviated septum, mucosal erosion of the nasal septum, and nasal septum perforation.

Atrophic Rhinitis

Thinned, dry nasal mucosa associated with atrophic rhinitis may cause capillaries to rupture and bleed.

Systemic Causes

Systemic diseases that lead to increased arterial or venous pressure, coagulation disorders, or changes in vascular tone can result in epistaxis.

Acute Febrile Infectious Diseases

Diseases such as influenza, hemorrhagic fever, measles, malaria, nasal diphtheria, and typhoid fever are associated with epistaxis. High fever, hyperemia, congestion, swelling, or dryness of the nasal mucosa from these conditions can lead to capillary rupture and bleeding, typically from the anterior nasal cavity, with minimal blood loss.

Cardiovascular Diseases

Conditions such as hypertension, arteriosclerosis, and congestive heart failure are often associated with epistaxis due to increased arterial pressure. This type of bleeding is often preceded by warning signs such as dizziness, headache, or a sensation of blood rushing in the nasal cavity. It is typically unilateral, arterial, pulsatile in nature, and rapid in onset, often originating from the posterior nasal cavity, such as the inferior meatus or olfactory groove.

Blood Disorders

Diseases involving abnormal coagulation mechanisms, such as hemophilia, fibrinogen formation disorders, paraproteinemia (e.g., multiple myeloma), and connective tissue diseases, may cause epistaxis due to coagulation abnormalities. Frequent use of anticoagulant medications is also a common cause of nosebleeds.

Platelet disorders, including thrombocytopenic purpura, leukemia, and aplastic anemia, may also result in epistaxis. Bleeding in these conditions often involves bilateral, persistent oozing that may recur frequently and is often accompanied by bleeding in other parts of the body.

Chronic Liver, Kidney Diseases and Rheumatic Fever

Liver dysfunction often leads to coagulation disorders, uremia increases the likelihood of small blood vessel injury, and rheumatic fever, which is more common in children, can predispose to epistaxis.

Endocrine Disorders

Hormonal imbalances, primarily seen in women, may result in epistaxis. Adolescent females may experience nosebleeds during menstruation, while menopausal or pregnant women may also exhibit epistaxis, potentially related to increased capillary fragility.

Hereditary Hemorrhagic Telangiectasia (HHT)

This condition often has a family history and is an autosomal dominant genetic disorder involving structural abnormalities of blood vessels. The primary pathological changes include the lack of elastic fibers and smooth muscle in small blood vessels. Capillaries, small arteries, and small veins have thin walls that consist only of a single layer of endothelial cells, with no contractile ability, leading to localized vascular dilation, tortuosity, fragility, and bleeding. Clinical features include recurrent spontaneous or minor trauma-induced bleeding at fixed locations. The most common manifestations are epistaxis, gingival bleeding, and skin bleeding. In rare cases, there may also be repeated episodes of hematemesis, melena, hemoptysis, hematuria, menorrhagia, or bleeding in the fundus or intracranial regions.

Others

Nutritional Deficiency or Deficiency of Vitamins C, K, P, or Calcium

Vitamin C and P deficiencies increase capillary fragility and permeability. Vitamin K is essential for prothrombin formation, and calcium is indispensable in the coagulation process.

Poisoning

Exposure to chemicals such as phosphorus, mercury, arsenic, or benzene can disrupt the hematopoietic system. Long-term use of salicylates may lead to a reduction in plasma prothrombin levels.

Examinations

Anterior Rhinoscopy

This method can be used to detect bleeding in the anterior part of the nasal cavity, such as examining whether there are dilated blood vessels or mucosal erosions in the bleeding-prone area of the anterior-inferior nasal septum, or if there is nasal septal perforation.

Figure 1 Vascular dilation in Little's area on the left side of the nasal septum

Nasal Endoscopy

Nasal endoscopy offers a distinct advantage in locating areas of bleeding, particularly in the posterior nasal cavity and the olfactory cleft. Before performing the examination, adequate mucosal decongestion and surface anesthesia are required. The examination may focus on regions prone to nosebleeds, such as the anterior-inferior nasal septum, posterior inferior meatus (Woodruff's nasopharyngeal venous plexus), posterior-inferior nasal septum, posterior nasal choanae, and the olfactory cleft.

Laboratory Tests

Blood routine tests can determine the extent of blood loss and presence of anemia by assessing hemoglobin levels. Coagulation function and platelet count tests help identify the cause of epistaxis.

Imaging

Digital subtraction angiography (DSA) and CT angiography (CTA) are useful for locating the specific blood vessels responsible for persistent posterior nasal bleeding, particularly traumatic pseudoaneurysms. MRI can assist in identifying intracranial vascular malformations in patients with hereditary hemorrhagic telangiectasia, providing further diagnostic clarity.

Treatment

Treatment Principles

Patients with long-standing, recurrent, and minor nosebleeds require a comprehensive evaluation to identify the underlying cause. Those presenting with significant bleeding need immediate hemostasis before investigating the etiology. Unlike anterior nasal bleeding, posterior nasal bleeding often originates from arterial sources, with a larger volume of blood loss that is more challenging to control. Patients with severe bleeding may experience emotional tension and fear, and calming them is important to promote stability. Identifying which nostril the bleeding originates from, and performing a thorough nasal endoscopy, aids in selecting the appropriate method for hemostasis.

General Management

Patients should be seated or positioned in a semi-reclined posture and encouraged to avoid swallowing blood to prevent gastric irritation and vomiting. Those in shock should be positioned flat with the head low, following first-aid principles for hypovolemic shock.

Local Management

In most cases, the bleeding originates from the anterior-inferior nasal septum (bleeding-prone area) and involves minimal blood loss. Patients may manually compress the nasal ala bilaterally for 10 to 15 minutes to control bleeding, while cold compresses (e.g., ice packs or wet towels) are applied to the forehead and nape of the neck to promote vasoconstriction. In cases of more severe bleeding, vasoconstrictor-soaked cotton swabs may be inserted into the nasal cavity to temporarily stop bleeding by constricting nasal mucosal vessels, thereafter allowing exploration of the bleeding site. Under nasal endoscopy, suction devices may be used to aspirate blood while locating the bleeding source.

Common methods of hemostasis include:

Cauterization

This technique is suitable for recurrent minor bleeding where the bleeding site is clearly identified. It works by destroying the capillary network at the bleeding site, sealing or coagulating the vessels to achieve hemostasis. Conventional methods include chemical cauterization or electrocautery. Smaller cauterization areas are preferred to minimize tissue damage. Excessively deep cauterization should be avoided, and an ointment is usually applied to the area after the procedure. Electrocautery is less frequently used now due to its risks of mucosal ulceration or cartilage necrosis, which may exacerbate bleeding if improperly performed.

In recent years, YAG lasers, radiofrequency, microwave, cryoplasma, or bipolar electrocautery are increasingly utilized. These updated methods allow for better control, mild cauterization, and minimal tissue damage. When performed under the guidance of nasal endoscopy, the accuracy and effectiveness of the procedure improve significantly. Care must be taken to avoid simultaneous cauterization of symmetrical areas on both sides of the nasal septum or prolonged cauterization to prevent nasal septal perforation.

Packing Method

This method is suitable for cases with severe bleeding, a large oozing surface, or an unclear bleeding location. Common techniques include the following four methods:

Absorbable Material Packing for the Anterior Nasal Cavity

This approach is suitable for cases of diffuse nasal mucosal bleeding with minimal blood loss. Absorbable materials such as gelatin sponges may be used and are often combined with coagulant agents like thrombin powder. The advantage of this method is that the packing material can be partially absorbed by tissues, avoiding mucosal damage and re-bleeding when removing the packing materials.

Figure 2 Nasal cavity packing method

Gauze Packing for the Anterior Nasal Cavity

This is a commonly used and effective method for severe bleeding, especially when the source is unclear, in cases of nasal mucosal tears caused by trauma, or when other methods fail.

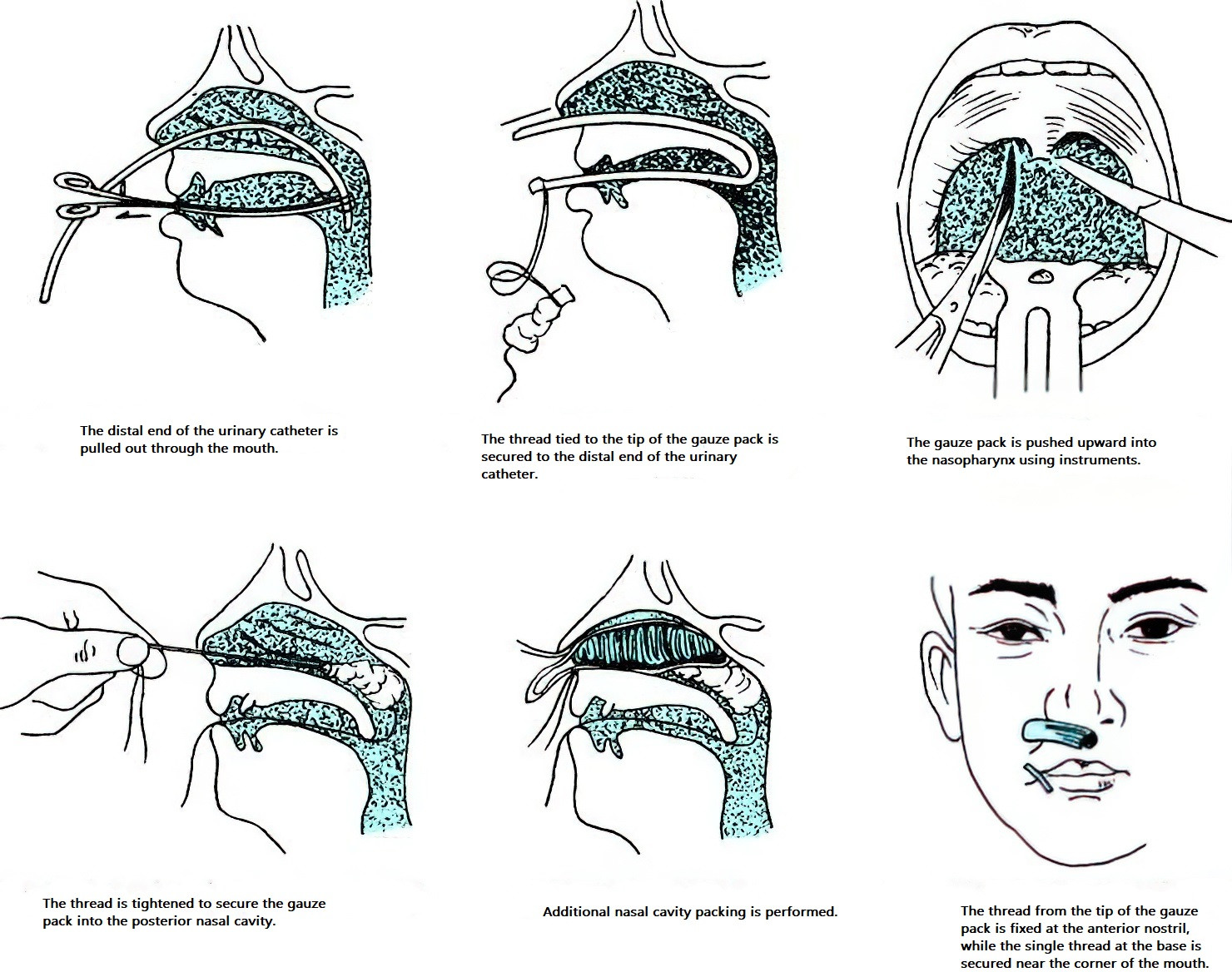

Figure 3 Posterior nasal packing method

Materials

Available options include petrolatum gauze, gauze coated with antibiotic ointment, or iodoform gauze.

Method

One end of the gauze is folded approximately 10 cm to create a strong double layer. The folded end is tightly placed in the posterior upper part of the nasal cavity. The two layers are then separated, with the shorter end pressed against the upper nasal cavity and the longer end laid across the nasal floor to form an outward-opening “pocket.” The remaining length of the gauze is inserted deep into the “pocket” in a layered manner, filling the nasal cavity from top to bottom and back to front with appropriate tension. If blood continues to flow into the oropharynx after packing, the gauze must be removed and repacked, or posterior nasal packing may be considered.

Precautions

Petrolatum gauze is generally left in place for 24–48 hours. If extended packing time is necessary, antibiotics are used to prevent infection, but the packing should not remain for more than 3–5 days to avoid pressure necrosis and infection. Antibiotic ointment gauze and iodoform gauze may be retained slightly longer if required.

Posterior Nasal Packing

If anterior gauze packing fails to stop the bleeding, posterior nasal packing is employed.

Procedure

A cone-shaped gauze pack or a pillow-shaped gauze pack slightly larger than the posterior nares is prepared. Two thick silk threads are tied to the tip of the gauze pack, and one thread is attached to the base.

A small-diameter urinary catheter is passed through the anterior nostril on the bleeding side, traveling through the nasal cavity and nasopharynx to the oropharynx. The distal end of the catheter is retrieved through the mouth using long curved forceps, while the proximal end remains outside the anterior nostril.

The silk threads tied to the tip of the gauze pack are securely attached to the catheter's distal end.

The catheter’s proximal end is pulled to draw the gauze pack into the oral cavity. The pack is positioned past the soft palate into the nasopharynx, while the silk threads are gently tightened to press the gauze firmly against the posterior nares.

Additional petrolatum gauze is used to pack the nasal cavity.

The silk thread exiting from the pack's tip is tied to a small piece of gauze and fixed at the anterior nostril.

The thread from the pack's base is drawn out of the oral cavity and loosely fixed near the corner of the mouth.

Precautions

This procedure must be performed under sterile conditions. Antibiotics should be used to prevent infection during the retention period, which generally does not exceed three days and should not last more than 5–6 days. In elderly patients, an assessment of cardiopulmonary function is essential before performing this procedure.

Removal

The nasal packing is removed first, followed by extraction of the gauze pack via the silk thread exiting the oral cavity, assisted by vascular forceps if necessary.

Balloon or Water-Bag Compression in the Nasal Cavity or Nasopharynx

A finger-glove or pre-manufactured balloon device is fastened to the distal end of a urinary catheter, inserted into the nasal cavity or nasopharynx, and inflated with air or water to compress the bleeding site. This method has been developed as an alternative to posterior nasal packing. Balloon devices specifically designed for nasal and posterior nares bleeding are now available in clinical practice. These devices are simple, convenient, and less painful for patients.

Vascular Ligation

This method may be employed for severe bleeding. For bleeding below the middle turbinate's plane, the maxillary artery or external carotid artery may be ligated. For bleeding above this plane, the anterior ethmoidal artery can be ligated. Bleeding in the anterior part of the nasal septum may require ligation of the superior labial artery. This technique is relatively rare in modern clinical practice.

Vascular Embolization

This method is used for refractory cases of epistaxis. Endovascular embolization involves catheterizing the femoral artery and advancing the catheter to the target blood vessel. Using digital subtraction angiography (DSA) and superselective embolization techniques, the responsible vessel is identified and embolized.

Common embolic agents include:

- Microparticles, such as polyvinyl alcohol foam, gelatin sponges, silk particles, or segments of thread.

- Coils, including tungsten-steel coils, mechanically detachable tungsten-steel microcoils, and electrolytically detachable platinum microcoils.

- Balloons.

- Liquid embolic agents.

This method is precise, efficient, safe, and reliable. However, it is costly and carries certain risks, including hemiplegia, aphasia, or transient vision loss.

Systemic Treatment

The causes and severity of epistaxis vary widely. Treatment should not focus solely on local hemostasis but should address underlying conditions when significant nasal or sinus pathology, systemic diseases, or substantial blood loss are present. Depending on the severity, measures may include oral, intramuscular, or intravenous use of hemostatic drugs, supplementation of essential vitamins, and correction of anemia or shock in relevant cases. Severe cases may require hospitalization for observation, monitoring of blood loss, and management of anemia or shock. Nasal packing may reduce arterial oxygen tension and increase carbon dioxide tension, necessitating careful monitoring of cardiac, pulmonary, and neurological function in elderly patients, with oxygen supplementation as needed.

Other Treatments

Recurrent bleeding in the anterior-inferior nasal septum may be managed with mucosal scratching or submucosal stripping of the nasal septum's mucoperiosteum.

In cases of hereditary hemorrhagic telangiectasia, full-thickness facial skin flaps may be transplanted to perform nasal septal reconstruction.

Cases due to systemic diseases require concurrent treatment of the underlying condition by the appropriate specialist.