Fungal rhinosinusitis (FRS) is a specific infectious disease commonly seen in clinical settings. Conventional perspectives suggest that fungal rhinosinusitis often occurs in individuals who have been using antibiotics, corticosteroids, or immunosuppressants for prolonged periods, or in those undergoing radiation therapy. It may also develop in cases of chronic debilitating diseases such as diabetes or extensive burns, which lead to reduced immunity. However, in recent years, it has been observed that otherwise healthy individuals can also develop fungal rhinosinusitis, potentially due to localized reductions in the body's ability to resist fungal invasion. The incidence of fungal rhinosinusitis has shown an upward trend in recent years, possibly linked to the widespread inappropriate use of antibiotics, environmental pollution, or improved detection rates due to increased health awareness and advancements in imaging technologies.

Etiology

The common pathogenic fungi include Aspergillus, as well as other species such as Monilia, Rhinosporidium seeberi, Mucoraceae, and Sporothrix schenckii. Aspergillus, a type of ascomycete, is widely distributed in nature and is classified as an opportunistic pathogen, typically causing infections in individuals with weakened systemic immunity or reduced local resistance, such as in the sinuses. The primary pathogenic species of Aspergillus include A. fumigatus and A. nigrae, with the former being more common. Infections may involve a single Aspergillus species or multiple species simultaneously. Occupational exposure appears to be related to Aspergillus infections, which are more frequently observed in occupations such as bird handlers, grain storage workers, farmers, and brewery workers. Mucoraceae, another opportunistic pathogen, is known for its proclivity to invade blood vessels, particularly arteries, spreading along the vascular structures to cause arteritis, thrombosis, infarction, and tissue necrosis. Although less common, nasal and cerebral forms of Mucoraceae infections are extremely aggressive, with rapid progression and high mortality rates.

Clinical Types and Pathology

Based on pathological findings, fungal rhinosinusitis can be categorized into the following clinical types:

Noninvasive Fungal Rhinosinusitis (NIFRS)

Pathologically, the fungal infection remains confined to the sinus cavity, without invasion of the sinus mucosa or bony walls.

Fungus Ball (FB)

This is the most common subtype. The lesions in the sinus typically consist of cheese-like or necrotic retained material that appears as dark brown or gray-black masses. The growing lesions can compress the sinus walls, leading to thinning of the bone due to pressure resorption. Under microscopy, the sinus material reveals large amounts of fungal hyphae, spores, degenerated white blood cells, and epithelial cells. The sinus mucosa shows edema or hyperplasia but lacks fungal invasion.

Allergic Fungal Rhinosinusitis (AFRS)

The lesions exhibit viscous, jam-like material that appears yellow-green or brown. Microscopic features include:

- On HE staining, amorphous pale eosinophilic or basophilic allergic mucin is observed, which contains large numbers of eosinophils and Charcot-Leyden crystals.

- Gomori staining (hexamine silver staining) reveals abundant fungal hyphae, either singly or in clusters. The sinus mucosa displays edema or hyperplasia, but fungal invasion is absent.

Invasive Fungal Rhinosinusitis (IFRS)

Pathologically, the fungal infection is not confined to the sinus cavity but invades the sinus mucosa and bony walls, subsequently spreading beyond the sinuses to areas such as the orbit, anterior cranial base, or pterygopalatine fossa. The lesions in the sinuses often include necrotic tissue, cheese-like material, or granulomatous material, with abundant viscous or bloody secretions. Under microscopy, large amounts of fungi can be observed, with fungal invasion of the sinus mucosa, bone, and blood vessels, leading to vasculitis, vascular embolism, bone destruction, and tissue necrosis. Based on the onset and clinical features, IFRS can be further divided into the following types:

Acute Invasive Fungal Rhinosinusitis (AIFRS)

This type presents with rapid pathological progression and extension to surrounding structures and tissues. Early stages may involve the lateral nasal wall, anterior, superior, and inferior walls of the maxillary sinus, and spread to the face, orbit, and hard palate. Later stages may result in destruction of the nasal roof, ethmoid roof, or sphenoid walls, with potential intracranial invasion and hematogenous dissemination to organs such as the liver, spleen, and lungs.

Chronic Invasive Fungal Rhinosinusitis (CIFRS)

This type progresses more slowly, with fungal invasion initially confined to the sinus mucosa and bony walls. In advanced stages, it may spread to surrounding structures and tissues.

Histopathological examination remains the definitive basis for distinguishing between noninvasive and invasive fungal rhinosinusitis by determining the presence of fungal invasion in the sinus mucosa or bone. Routine HE staining has a positive detection rate of approximately 60%, while Gomori staining achieves a positive rate exceeding 95%.

Clinical Manifestations and Diagnosis

The clinical manifestations of different types of fungal rhinosinusitis (FRS) vary significantly.

Fungus Ball

Fungus ball is more common in females than males, and patients are usually immunocompetent. The condition typically involves a single affected sinus, with the maxillary sinus being the most frequently involved, followed by the sphenoid and ethmoid sinuses, with the frontal sinus being rare. The clinical features are similar to those of chronic rhinosinusitis, such as unilateral nasal obstruction, purulent nasal discharge, nasal discharge mixed with blood, or a foul smell. In some cases, there may be no symptoms, with the condition being discovered incidentally during imaging studies of the sinuses. Large fungus balls may cause facial swelling and pain (related to compression of the infraorbital nerve), but involvement of surrounding structures such as the orbit is uncommon. Systemic symptoms are generally absent.

CT imaging of the sinuses typically shows unevenly increased density in the affected sinus, with calcified spots of high density observable in approximately 70% of cases. Expansive changes in the sinus walls or pressure-induced bone resorption may be present, along with evidence of bony hyperplasia. CT imaging serves as an important preoperative diagnostic reference, while definitive diagnosis relies on pathological examination.

Figure 1 CT imaging of fungal ball-type rhinosinusitis

Allergic Fungal Rhinosinusitis (AFRS)

AFRS commonly occurs in otherwise immunocompetent adults and young people, often with an atopic predisposition. It is characterized by recurrent chronic rhinosinusitis with nasal polyps and, in some cases, comorbid asthma. Many patients have a history of one or more prior surgeries for sinusitis and nasal polyps. The condition often has an insidious onset and progresses slowly, typically involving multiple bilateral sinuses. Clinical features resemble those of chronic rhinosinusitis with nasal polyps. In rare cases, AFRS may present as sinus masses, most commonly affecting the maxillary, ethmoid, and frontal sinuses.

Intranasal expansion of the disease can cause sinus enlargement and pressure-induced bone resorption of the sinus walls. Clinically, progressive swelling in the orbital or maxillofacial area may occur; this swelling is usually painless, immobile, firm, and irregularly shaped, resembling mucous retention cysts, mucopyoceles, or even malignant tumors. Further enlargement may lead to orbital compression, resulting in proptosis, displacement of the eyeball, restricted eye movement, diplopia, and ptosis. Severe cases may present with swelling and pain in the periorbital soft tissues, with invasion of the orbit and optic nerve causing vision loss or blindness.

CT imaging of the sinuses often reveals centrally high-density allergic mucin within the lesion (appearing homogeneously ground-glass-like or highly irregular with star-shaped calcifications), with findings being more prominent in bone window settings. MRI imaging typically shows centrally low signal intensity with surrounding high signal intensity.

Diagnostic criteria primarily include:

- A history of atopy or asthma, along with multiple nasal polyps or prior surgeries, most commonly in young individuals.

- Positive allergen test results indicating a type I hypersensitivity reaction.

- Characteristic findings on CT or MRI imaging of the sinuses.

- Typical histopathological findings.

- Gomori methenamine silver staining demonstrating the presence of fungal hyphae within the lesions, without fungal invasion of the sinus mucosa or bone, as confirmed by fungal culture.

Acute Invasive Fungal Rhinosinusitis (AIFRS)

This type is most frequently observed in individuals with impaired or deficient immune function, with the primary causative fungi being Aspergillus and Mucoraceae. The onset is abrupt, the progression is rapid, and the prognosis is poor, with high mortality rates. Clinical manifestations include fever, nasal cavity and sinus structural destruction, necrosis, extensive purulent crusts, swelling and pain in the periorbital and cheek areas, or symptoms such as proptosis, conjunctival congestion, ophthalmoplegia, visual impairment, and retrobulbar pain. Palatal defects, severe headache, intracranial hypertension, seizures, altered consciousness, or hemiplegia may occur. Some patients may present with orbital apex syndrome or cavernous sinus thrombophlebitis. Without timely intervention, death may result within a matter of days.

The acute onset, short disease course, and rapid progression, combined with a history of immune compromise or deficiency, suggest the diagnosis, particularly in the presence of invasive clinical features. Imaging studies such as CT or MRI typically reveal involvement of the nasal cavity and multiple sinuses, with extensive bony destruction and extension to the face, orbit, skull base, or pterygopalatine fossa. The definitive diagnosis is established based on histopathological evidence of fungal invasion in affected tissues, sinus mucosa, or bone.

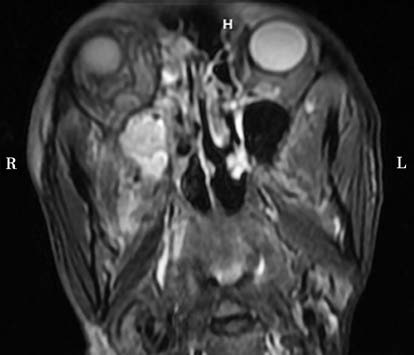

Figure 2 MRI imaging of acute invasive fungal rhinosinusitis

Chronic Invasive Fungal Rhinosinusitis (CIFRS)

CIFRS also tends to occur in individuals with compromised immune function. Common causative fungi include Aspergillus, Mucoraceae, Alternaria, and Candida species. The disease is characterized by slow, progressive tissue invasion.

Early diagnosis and appropriate treatment provide the potential for a cure in most cases. In later stages, treatment becomes more challenging, with higher rates of recurrence and poorer outcomes. Early in its course, the clinical, pathological, and imaging features of CIFRS may be similar to those of noninvasive fungal rhinosinusitis, leading to potential misdiagnoses. Clinical suspicion should be raised in the presence of hemopurulent nasal discharge or severe headaches. Imaging features such as involvement of multiple sinuses or evidence of bony destruction, combined with intraoperative findings of mud-like material and extensive thick pus in the sinus cavity, highly swollen, dark-red, fragile, and granular mucosa, or black necrotic mucosal changes, may suggest early-stage CIFRS.

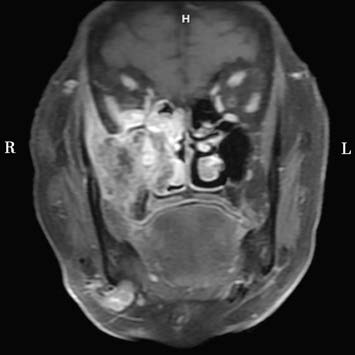

Figure 3 MRI imaging of chronic invasive fungal rhinosinusitis

The definitive diagnosis is confirmed through histopathological evidence of fungal invasion in the sinus mucosa and bone. In advanced stages, surrounding structures and tissues may become involved, with clinical features resembling those of AIFRS but with a longer disease course, helping to differentiate from the acute form.

Treatment

Treatment Principles

The primary treatment approach involves surgery, with the addition of antifungal medications for invasive fungal rhinosinusitis.

Surgical Treatment

For noninvasive fungal rhinosinusitis, sinus lesion clearance is performed to establish adequate sinus ventilation and drainage while preserving the sinus mucosa and bone walls. For invasive fungal rhinosinusitis, debridement surgery is required. This involves not only the removal of diseased tissues from the nasal cavity and sinuses but also the extensive resection of affected sinus mucosa and bone walls. The choice between conventional surgical approaches and transnasal endoscopic surgery is made based on the extent of the lesions; however, transnasal endoscopic surgery is now widely utilized in clinical practice.

Drug Therapy

Antifungal medications are not typically required following surgery for noninvasive fungal rhinosinusitis. Postoperative treatment for allergic fungal rhinosinusitis involves the use of corticosteroids to effectively control the condition, with prednisolone or intranasal corticosteroids commonly employed. For invasive fungal rhinosinusitis, antifungal medications are essential after surgery. Commonly used antifungal drugs include itraconazole, amphotericin B, clotrimazole, nystatin, and flucytosine. Itraconazole is effective against Aspergillus species and has relatively mild side effects. Amphotericin B is a broad-spectrum antifungal agent effective against species such as Cryptococcus, Histoplasma, Blastomyces, Paracoccidioides, Coccidioides, Aspergillus, Mucoraceae, and some Candida. Although antifungal treatments can sometimes achieve good control in cases of acute invasive fungal rhinosinusitis, the associated side effects of these medications can be significant.

Other Treatments

Some researchers recommend intermittent oxygen therapy for late-stage chronic invasive fungal rhinosinusitis and acute invasive fungal rhinosinusitis. During the treatment period, the use of antibiotics and immunosuppressants should be discontinued, and attention should be focused on improving overall systemic health.

Prognosis

Fungus ball typically has a favorable prognosis after surgical treatment, with most cases being curable. Allergic fungal rhinosinusitis generally shows good outcomes when postoperative corticosteroid therapy is appropriately applied. Chronic invasive fungal rhinosinusitis is often cured with a single surgery if diagnosed and treated in the early stages; however, advanced-stage cases have poor treatment outcomes, a tendency for recurrence, and an unfavorable prognosis. Acute invasive fungal rhinosinusitis is associated with an extremely high mortality rate.