Allergic rhinitis (AR), also known as atopic rhinitis, is a chronic inflammatory condition of the nasal mucosa that occurs in atopic individuals upon exposure to allergens. It is primarily mediated by IgE, which triggers the release of inflammatory mediators such as histamine, with the involvement of various immune cells and cytokines. The condition is characterized by nasal itching, sneezing, excessive nasal secretions, and nasal mucosal swelling. Its prevalence in the general population ranges from 10% to 25%, and recent years have seen an increasing trend in its incidence. Traditionally, allergic rhinitis is classified into perennial allergic rhinitis (PAR) and seasonal allergic rhinitis (SAR). The World Health Organization (WHO) initiative "Allergic Rhinitis and Its Impact on Asthma" (ARIA) categorizes AR into intermittent and persistent types based on the temporal characteristics of the disease. Additionally, AR is divided into mild and moderate-severe types depending on the impact on quality of life. This classification serves as the basis for selecting stepwise treatment approaches in clinical practice.

Pathogenesis

Type I hypersensitivity reaction mediated by IgE is the primary mechanism of allergic rhinitis. This involves the interaction of various immune cells, cytokines, and adhesion molecules. The disease progression occurs in two stages. In the sensitization stage, allergens stimulate the immune system, resulting in initial T-cell differentiation into Th2 cells. Th2 cytokines promote the differentiation of B cells into plasma cells, which produce IgE. The IgE binds to receptors on mast cells and basophils. Subsequently, in the elicitation stage, re-exposure to allergens in the nasal cavity leads to cross-linking of IgE molecules on mast cells and basophils (where an allergen bridges two IgE Fab regions), triggering degranulation of these cells. This releases histamine and other inflammatory mediators, which act on cells, blood vessels, and glands, causing a cascade of clinical manifestations.

Pathology

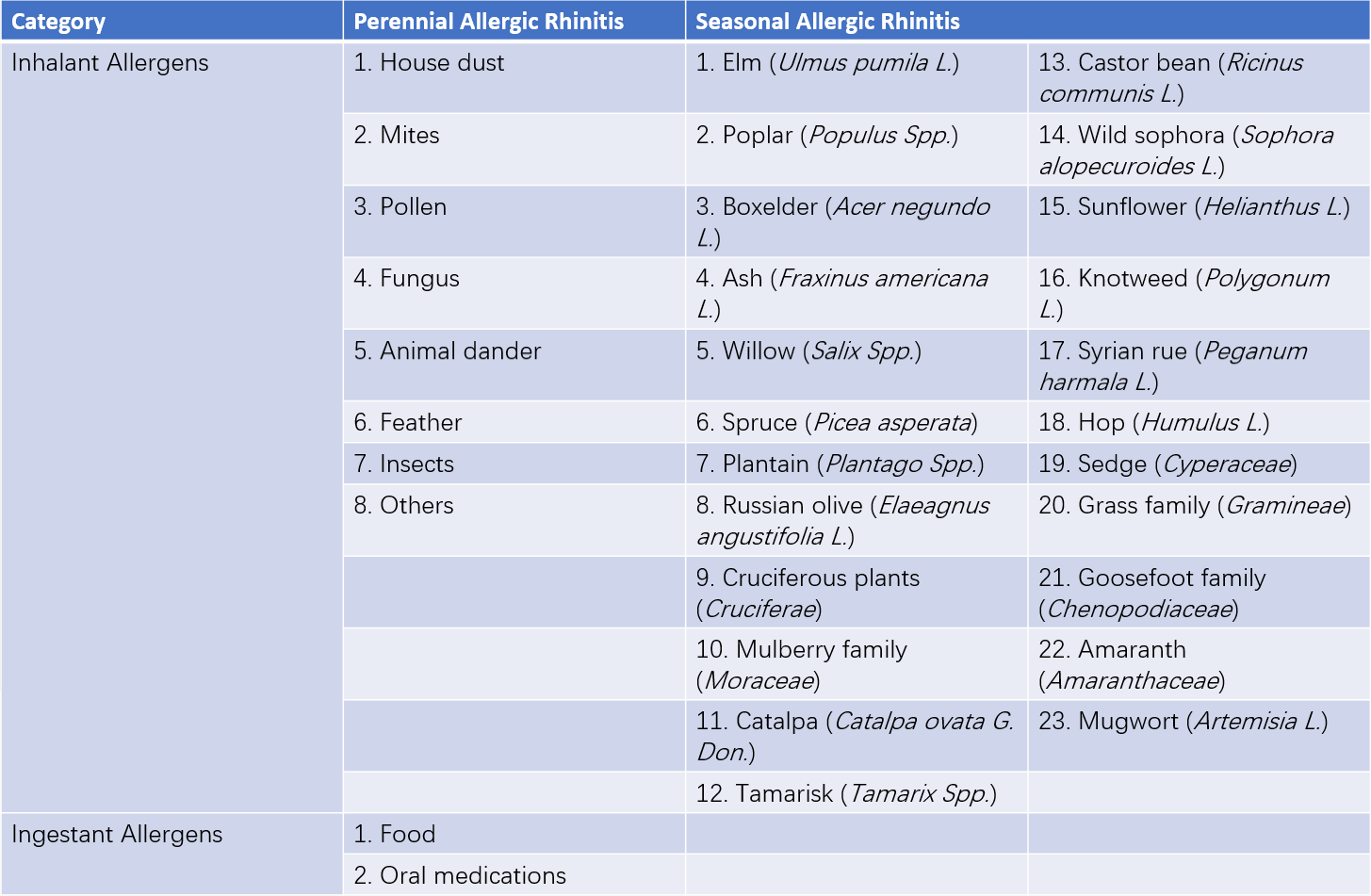

The fundamental pathological changes in allergic rhinitis involve the constriction of resistance blood vessels (pallor of nasal mucosa) or the dilation of capacitance blood vessels (pale blue discoloration of nasal mucosa) and increased capillary permeability (mucosal edema). There is infiltration of various immune cells, particularly eosinophils. Enhanced parasympathetic nerve activity results in glandular hyperplasia and excessive secretion (leading to increased mucus production), while heightened sensitivity of sensory nerves contributes to repeated sneezing. These pathological changes place the nasal mucosa in a hypersensitive state, making it susceptible to clinical symptoms of allergic rhinitis upon exposure to non-specific stimuli such as cold or heat. Perennial and seasonal allergic rhinitis differ in their triggering allergens.

Table 1 Common allergens in perennial allergic rhinitis and seasonal allergic rhinitis

Clinical Manifestations

The primary features of allergic rhinitis include nasal itching, paroxysmal sneezing, extensive watery nasal discharge, and nasal congestion.

Nasal Itching

When associated with allergic conjunctivitis, itching in the eyes and conjunctival hyperemia may also occur. Itching in the external auditory canal, soft palate, or pharynx may occasionally be present.

Sneezing

Sneezing occurs paroxysmally and varies from a few sneezes to dozens in a session. It typically happens in the morning, evening, or immediately following allergen exposure.

Nasal Discharge

Profuse watery discharge is a characteristic sign of increased nasal secretions.

Nasal Congestion

The severity of nasal congestion varies. It may be intermittent or persistent, unilateral, bilateral, or alternating between sides.

Reduced Sense of Smell

Significant nasal mucosal edema leads to olfactory dysfunction in some patients.

Examinations

Anterior Rhinoscopy or Nasal Endoscopy

The nasal mucosa often appears characteristically pale and edematous, although it may also present with congestion or pale blue discoloration. These findings are especially pronounced in the inferior turbinate. Watery secretions are frequently observed in the nasal cavity.

Identification of Allergenic Triggers

Methods include allergen skin prick testing (SPT), nasal mucosal provocation testing, and in vitro allergen-specific IgE testing. Among these, skin prick testing is the most commonly employed in clinical practice. In vitro allergen-specific IgE testing includes assessments of serum and nasal secretion IgE levels.

Diagnosis

The diagnosis is established based on typical symptoms and signs, along with the results of allergen testing. A differential diagnosis is necessary to distinguish allergic rhinitis from other types of non-allergic rhinitis, such as eosinophilic non-allergic rhinitis and vasomotor rhinitis. These conditions share several clinical symptoms and signs with allergic rhinitis but are characterized by negative allergen tests. In vasomotor rhinitis, an increase in eosinophils within nasal secretions is not observed. Allergic rhinitis may be complicated by or associated with conditions such as sinusitis, nasal polyps, bronchial asthma, and secretory otitis media. The coexistence of allergic rhinitis and asthma is common, with a bidirectional causal relationship often present. The "one airway, one disease" concept has therefore been proposed to emphasize the interconnected nature of these conditions.

Treatment

A stepwise treatment approach is employed based on the classification and severity of allergic rhinitis. The following options are available depending on the patient's condition: (1) avoidance of allergen exposure; (2) pharmacological therapy (symptomatic treatment); (3) immunotherapy (causal treatment); and (4) surgical interventions. From the perspectives of therapeutic efficacy and safety, an integrated treatment strategy targeting both the upper and lower respiratory tracts is important. Effective management of allergic rhinitis may prevent and alleviate asthma exacerbations.

Pharmacological Therapy

Intranasal Corticosteroids

Their pharmacological effects include inhibiting mast cells and basophils, suppressing mucosal inflammatory responses, reducing eosinophil counts, stabilizing the epithelial and vascular endothelial barriers of the nasal mucosa, and decreasing the sensitivity of nasal gland cholinergic receptors. Due to their local absorption, intranasal corticosteroids have low systemic bioavailability, rapid onset of action, and favorable safety profiles. Local side effects may include nasal bleeding.

Antihistamines

These agents competitively block histamine receptors on effector cell membranes, thereby preventing histamine-mediated biological effects. They rapidly relieve nasal itching, sneezing, and excessive nasal secretions but are less effective in alleviating nasal congestion. First-generation antihistamines often have central nervous system depressant effects, and caution is required for individuals engaged in precision operations or driving. Additionally, first-generation antihistamines possess anticholinergic actions, which may result in side effects such as dry mouth, blurred vision, urinary retention, and constipation. Second-generation antihistamines address the central depressant effects of their predecessors and exhibit stronger H1 receptor antagonism, along with certain anti-inflammatory properties. However, some drugs, such as terfenadine and astemizole, may carry risks of severe or even fatal cardiac complications.

Mast Cell Membrane Stabilizers

Cromones prevent mast cell degranulation and the release of mediators. Due to their delayed onset of action (often over one week), they are mainly suitable for mild cases or as preventive therapy.

Anti-Leukotriene Agents

Leukotrienes, lipid metabolites of cell membranes, were initially identified as mediators of bronchial smooth muscle contraction. Recent studies highlight their role in the pathogenesis of allergic rhinitis. Leukotriene receptor antagonists serve as an important treatment for allergic rhinitis, particularly in patients with comorbid asthma.

Intranasal Decongestants

These are typically used as adjunctive therapy to relieve nasal congestion. Their continuous use is recommended for no longer than seven days, as prolonged application may lead to medication-induced rhinitis.

Anticholinergic Agents

These agents reduce nasal secretions but are ineffective against nasal itching and sneezing.

Saline Nasal Irrigation

Saline irrigation mitigates symptoms by reducing the local allergen concentration in the nasal mucosa.

Pollen Barriers

Pollen barriers reduce or block contact between the nasal mucosa and various allergens, thereby alleviating or eliminating symptoms.

Allergen-Specific Immunotherapy (ASIT)

Allergen-specific immunotherapy is primarily used for managing Type I hypersensitivity reactions caused by inhaled allergens. Through repeated subcutaneous injections or sublingual administration of increasing concentrations of specific allergens, the patient's tolerance to sensitizing allergens is enhanced. This approach aims to reduce or eliminate symptoms upon future exposure to the allergen. The treatment cycle consists of an initial dose accumulation phase followed by a dose maintenance phase. A total treatment duration of over two years is generally recommended.

Surgical Treatment

Selective neural surgeries, such as vidian nerve resection, may be considered in cases where pharmacological and/or immunotherapy yield unsatisfactory results.