Acute sinusitis often follows acute rhinitis. Its pathological changes primarily involve acute catarrhal or purulent inflammation of the sinus mucosa. In severe cases, it may affect the bony structures, surrounding tissues, and adjacent organs, potentially leading to serious complications.

Since the sinus mucosa is continuous with the nasal mucosa, sinus inflammation often occurs after or simultaneously with nasal inflammation. Among all sinuses, the maxillary sinus is most frequently affected, followed by the ethmoid sinus. Inflammation of the anterior group of sinuses is more common than the posterior group. The occurrence of sinusitis is related to anatomical features:

- The small sinus ostia and narrow, winding nasal passages make obstruction likely, resulting in impaired aeration and drainage of the sinuses.

- The continuity of the sinus and nasal mucosa allows nasal inflammation to involve the sinus mucosa.

- The proximity of the sinus ostia to each other means that inflammation in one sinus can spread to others. For example, the frontal sinus, anterior ethmoid sinus, and maxillary sinus all drain into the semilunar hiatus in the middle meatus. Since the maxillary sinus ostium is located in the lower part of the semilunar hiatus, secretions from the frontal or anterior ethmoid sinuses can flow into the maxillary sinus, increasing the risk of maxillary sinusitis. This explains why maxillary sinusitis is the most common.

- Specific anatomical characteristics of the sinuses also contribute to disease susceptibility. The maxillary sinus, the largest sinus, has a high ostium, making drainage difficult during inflammation. The ethmoid sinus has a honeycomb-like structure with small openings, which are prone to obstruction during mucosal swelling, leading to poor drainage. Although the frontal sinus is located higher with a lower ostium, its drainage pathway can be narrowed by well-developed frontal recess cells (agger nasi cells) and the nasal bulla, making frontal sinusitis more likely. The sphenoidal sinus, located within the sphenoid bone and behind the posterior ethmoid sinus, has a solitary opening, making it less frequently affected. The development of the sinuses varies with age; the maxillary and ethmoid sinuses develop first, hence children can develop sinus infections early in life.

This section focuses on bacterial-induced purulent sinusitis. Fungal sinusitis is covered in the related section.

Etiology

Local Factors

Nasal Cavity Diseases

Acute or chronic rhinitis, deviated nasal septum, hypertrophic middle turbinate, allergic rhinitis, nasal polyps, foreign bodies, and nasal tumors can all lead to obstruction of the ostiomeatal complex, superior nasal meatus, or sphenoethmoidal recess, impairing sinus aeration and drainage, ultimately resulting in sinusitis.

Infectious Foci in Adjacent Organs

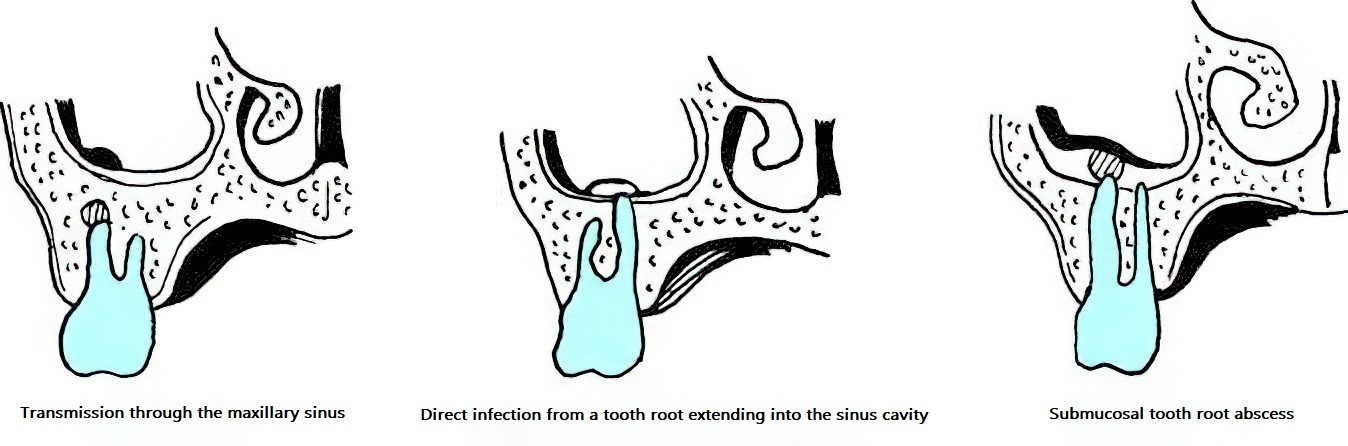

Conditions such as tonsillitis and adenoiditis can cause concurrent nasopharyngeal and nasal inflammation, triggering sinusitis. Periapical infections of the second premolar and first or second molars, tooth extraction injuries in the maxillary sinus, or the displacement of retained tooth roots into the maxillary sinus can result in odontogenic maxillary sinusitis.

Figure 1 Odontogenic maxillary sinusitis

Sinus Trauma or Foreign Bodies

Trauma-related sinus fractures, foreign object entry into the sinuses, improper swimming or nose-blowing after swimming, and contaminated water entering the sinuses are all potential causes of sinus infections.

Iatrogenic Infections

Prolonged placement of nasal packing may lead to local blood circulation issues, mucosal compression edema, and secondary infections, causing sinusitis. Additionally, prolonged packing can also impair sinus drainage and ventilation.

Barometric Changes

Rapid descent during high-altitude flights can create negative pressure within the sinuses, allowing nasal inflammatory or contaminated material to be aspirated into the sinuses, causing non-obstructive barosinusitis.

Systemic Factors

Systemic conditions that lower overall resistance, such as overwork, cold exposure, damp environments, malnutrition, vitamin deficiency, or living and working in unsanitary conditions, are common contributors to the onset of acute sinusitis. Furthermore, systemic diseases like anemia, diabetes, hypothyroidism, hypopituitarism, upper respiratory tract infections, and acute infectious diseases (e.g., influenza, measles, scarlet fever, diphtheria) can also trigger sinusitis.

Pathogens

The most commonly observed pathogens include pyogenic cocci such as Streptococcus pneumoniae, Streptococcus hemolyticus, Staphylococcus aureus, and Moraxella catarrhalis. Bacilli, such as Haemophilus influenzae, Proteus, and Escherichia coli, are the next most common. Anaerobic bacterial infections are also relatively frequent. Sinusitis is often caused by mixed infections involving cocci and bacilli or aerobic and anaerobic bacteria.

Pathology

The pathological changes are similar to those in acute rhinitis and progress through three stages:

Catarrhal Stage

Initially, the sinus mucosa undergoes transient ischemia, followed by vasodilatation and hyperemia. The epithelium swells, the submucosa becomes edematous, and neutrophil and lymphocyte infiltration occurs. Ciliary movement slows down, and there is an increase in serous or mucous secretions.

Purulent Stage

Inflammation progresses, leading to epithelial necrosis, loss of cilia, small vessel hemorrhages, and a transformation of secretions to a purulent nature.

Complication Stage

The infection may invade the bone or spread hematogenously, causing complications such as osteomyelitis, orbital infections, or intracranial infections.

This pathological progression is not inevitable. Timely diagnosis and treatment allow most patients to achieve resolution during the catarrhal stage.

Clinical Manifestations

Local Symptoms

Nasal Obstruction

This symptom is often persistent on the affected side. If both sides are involved, bilateral persistent nasal obstruction occurs. It is caused by inflammatory swelling of the nasal mucosa and the accumulation of mucopurulent secretions in the common nasal meatus.

Purulent Nasal Discharge

A large amount of purulent or mucopurulent discharge is present in the nasal cavity, which is difficult to expel completely. Traces of blood may also appear in the discharge. Infections of the maxillary sinus, frontal sinus, and anterior ethmoid sinuses lead to secretions often localized in the middle meatus. Infections of the posterior ethmoid sinus result in secretions in the superior meatus, while secretions from sphenoid sinus infections originate in the sphenoethmoidal recess. In cases caused by anaerobic bacteria or Escherichia coli, the discharge may have a foul odor (commonly seen in odontogenic maxillary sinusitis). The purulent nasal discharge can flow backward into the nasopharynx and larynx, irritating the mucosa in these regions and leading to symptoms such as throat itchiness, nausea, cough, or sputum production.

Figure 2 Purulent secretions from sinusitis draining through the right middle meatus

Headache or Localized Pain

Pain is one of the most common symptoms during the acute phase of sinus inflammation. This occurs due to stimulation and compression of nerve endings by purulent secretions, bacterial toxins, and mucosal swelling. Headache associated with inflammation of the anterior sinuses typically occurs in the forehead or cheek area. In contrast, inflammation of the posterior sinuses often leads to pain at the base of the skull or occipital region.

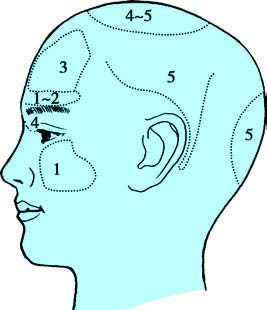

Figure 3 Surface projection areas of headache caused by sinusitis

1, Acute maxillary sinusitis

2, Acute frontal sinusitis

3, Chronic frontal sinusitis

4, Chronic ethmoid sinusitis

5, Chronic sphenoid sinusitis

The characteristics of headache caused by inflammation of specific sinuses are as follows:

Acute Maxillary Sinusitis

Pain is typically localized to the surface projection area of the maxillary sinus (cheek region), presenting as ipsilateral cheek pain or upper molar pain. The pain follows a diurnal pattern, being mild in the morning and worsening in the afternoon. This is related to the anatomy of the maxillary sinus, which is large in size with a high ostium. During the day, in the upright position, secretions in the sinus have difficulty draining. At night, while lying flat, secretions drain more easily through the sinus ostium. Consequently, pain is milder in the morning but gradually worsens during the day as secretions accumulate, peaking in the afternoon.

Acute Ethmoid Sinusitis

Pain is generally mild and localized to the surface projection of the ethmoid sinus (inner canthus or nasal root), but it may radiate to the top of the head. Headache associated with anterior ethmoid sinusitis may resemble that of acute frontal sinusitis, while posterior ethmoid sinusitis may mimic that of acute sphenoid sinusitis. There is typically no significant diurnal variation.

Acute Frontal Sinusitis

Pain presents as periodic "vacuum headache" localized to the forehead. The pain begins in the morning upon waking and gradually intensifies, peaking by midday and then subsiding in the afternoon, only to recur the following day. The periodic nature of the headache is related to the anatomy of the sinus drainage pathway. The frontal sinus ostium is located at its base, allowing secretions to drain through the frontal sinus drainage tract into the middle meatus. Blockage of the pathway, often caused by over-pneumatized anterior ethmoidal cells or agger nasi cells, leads to impaired drainage. The accumulation of secretions within the sinus during the day creates a vacuum, producing sharp vacuum pain. By afternoon, as secretions gradually drain, ventilation improves, and the pain subsides.

Acute Sphenoid Sinusitis

The sphenoid sinus is located deep within the sphenoid bone, and inflammation often causes deep-seated pain in the central skull or retro-orbital region. The pain may radiate to the vertex or behind the ears and occasionally lead to occipital pain. Pain tends to be milder in the morning but worsens in the afternoon, a pattern also related to the anatomical position of the sinus ostium.

Olfactory Disorders

Conductive hyposmia is commonly seen during acute inflammation due to nasal obstruction. In a few cases, sensory hyposmia occurs. While olfactory function may return to normal as nasal obstruction resolves in the former, the latter may result in permanent olfactory impairment.

Systemic Symptoms

Since acute sinusitis is frequently secondary to upper respiratory tract infections or acute rhinitis, existing symptoms often worsen. Systemic manifestations may include chills, fever, reduced appetite, constipation, and general malaise. Children and elderly individuals with weak constitutions may experience gastrointestinal symptoms such as vomiting and diarrhea, or lower respiratory tract symptoms such as coughing.

Examinations and Diagnosis

Detailed history taking and analysis are important, especially if the symptoms mentioned above occur during the resolution phase of acute rhinitis, which strongly suggests acute sinusitis. The following auxiliary examinations aid in diagnosis:

Examination of the Sinus Surface Projection Areas

Acute maxillary sinusitis may show redness, swelling, and tenderness in the cheek and lower eyelid area. Acute frontal sinusitis may present with redness and swelling in the forehead, tenderness and percussion pain in the upper medial corner of the orbit (corresponding to the base of the frontal sinus), and tenderness in the anterior wall of the frontal sinus. Acute ethmoid sinusitis may occasionally show redness and tenderness at the nasal root and inner canthus.

Anterior Rhinoscopy

Findings include congestion and swelling of the nasal mucosa, which are particularly pronounced in the middle turbinate and middle meatus. The nasal cavity often contains abundant mucopurulent or purulent secretions. Anterior sinus infections may produce mucopurulent or purulent secretions in the middle meatus, while posterior sinus infections may show similar secretions in the olfactory cleft. If the patient has recently blown their nose before the examination, these secretions in the middle meatus or olfactory cleft may temporarily disappear and can be observed again after postural drainage. Foul-smelling purulent secretions in one nasal cavity suggest odontogenic maxillary sinusitis in adults or a foreign body in children.

Nasal Endoscopy

Following mucosal decongestion using cotton swabs soaked with a decongestant (such as ephedrine or adrenaline) combined with a topical anesthetic (such as tetracaine), a nasal endoscopy is performed to examine the nasal anatomy. Specific attention is given to the middle meatus, olfactory cleft, sinus ostia, and adjacent mucosa for pathological changes. Observations include the source and nature of secretions (purulent, mucoid, or mucopurulent), the morphology of the sinus ostia, the degree of mucosal redness and swelling, the presence of polypoid changes, and any tumors, including their source and morphology. Nasal endoscopy allows for direct visualization of purulent secretions in the middle meatus, and samples can be collected for culture. This method is widely used in clinical practice and is an important diagnostic tool for sinusitis. Additionally, the removal of secretions under endoscopic guidance is also an effective treatment option for sinusitis.

Imaging

Computed tomography (CT) of the paranasal sinuses provides clear visualization of sinus mucosal thickening, the extent of sinus involvement, and the presence of bony destruction. CT is the preferred imaging modality for diagnosing sinusitis. Magnetic resonance imaging (MRI) better visualizes soft tissue abnormalities and is important for differentiating sinusitis from tumor-like lesions, but it is not the first choice for imaging in sinusitis. Plain X-rays are less useful for diagnosing sinusitis and are rarely used in current clinical practice.

Diagnostic Maxillary Sinus Puncture and Irrigation

In non-febrile patients with acute maxillary sinusitis, puncture may be performed under antibiotic control. Maxillary sinus puncture helps confirm the presence of purulent secretions, and if pus is detected, bacterial cultures and antibiotic sensitivity tests are conducted. Following irrigation of the sinus, antibiotics can be instilled into the sinus cavity, making this an effective treatment option. However, since puncture is an invasive procedure and is only applicable for maxillary sinus pathology, its clinical application has become less frequent.

Prevention

Improved physical fitness, better living and working environments, and prevention of colds and other acute infectious diseases are essential. For individuals with systemic diseases such as anemia or diabetes, active treatment of the underlying condition is important. Prompt and appropriate treatment of acute rhinitis and chronic inflammatory diseases of the nasal cavity, sinuses, pharynx, and oral cavity is also beneficial. Ensuring proper ventilation and drainage of the sinuses helps prevent sinusitis.

Treatment

Treatment Principles:

- Address the underlying cause.

- Relieve obstructions to sinus ventilation and drainage.

- Control the infection and prevent complications.

Local Treatment

Nasal Decongestants

Decongestants effectively reduce mucosal swelling in the nasal cavity and sinus ostia, improving sinus drainage. The duration of decongestant use should generally not exceed 7 days to minimize side effects and prevent medicamentous rhinitis.

Intranasal Corticosteroids

These are the first-line medications for the treatment of sinusitis. See the section on acute rhinitis treatment in this chapter for details regarding administration and precautions.

Nasal Irrigation

Special nasal irrigation devices are widely used in clinical practice for nasal irrigation. Solutions may include normal saline, hypertonic saline, or antibiotic/steroid solutions as needed. Irrigation is typically performed 1–2 times per day. The choice of solution is based on the specific condition of the patient. This method helps remove nasal secretions and improves the mucosal environment, contributing to disease management.

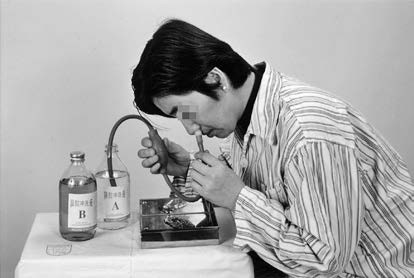

Figure 4 Nasal irrigation

Maxillary Sinus Puncture and Irrigation

This method is used for treating maxillary sinusitis and also aids in diagnosis. It is performed after systemic symptoms subside and local inflammation is under control. Irrigation is carried out once a week until no purulent fluid is observed. Post-irrigation, antibiotics (e.g., tinidazole or metronidazole solutions) can be instilled into the sinus cavity, and some patients may recover after a single session.

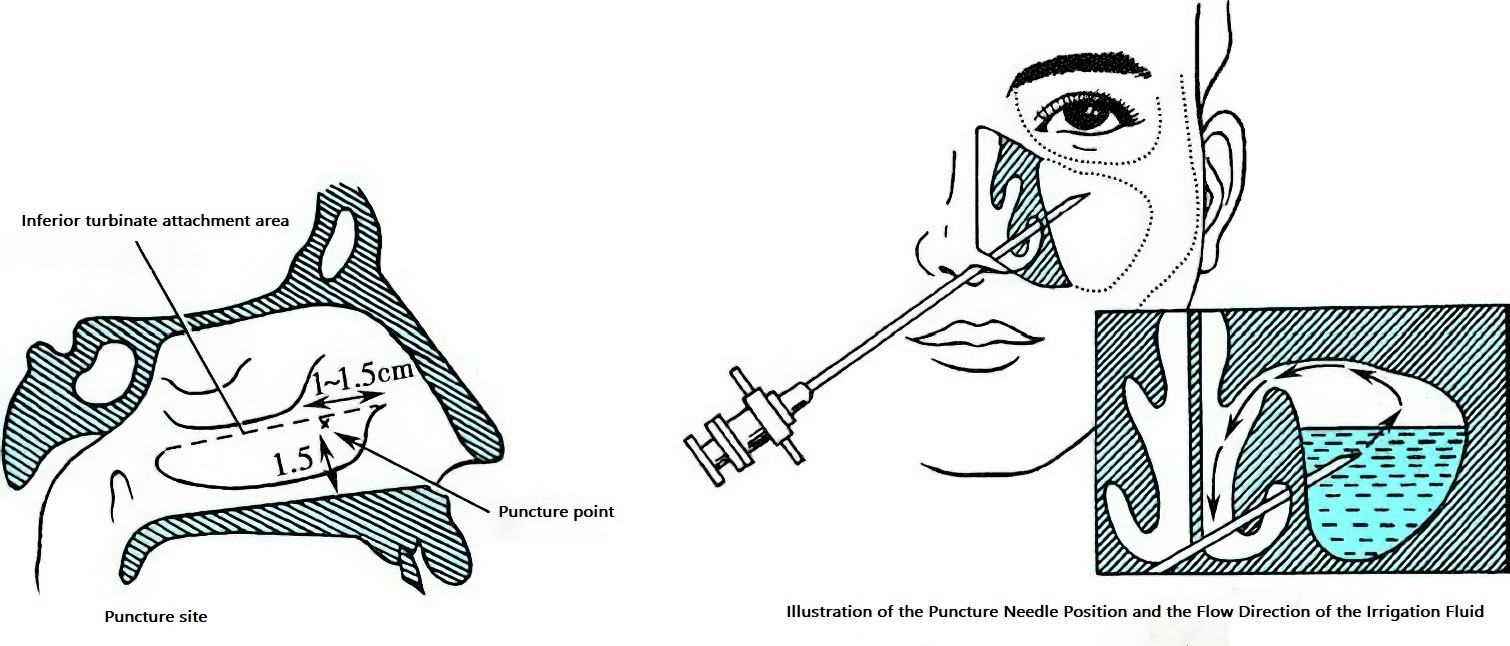

Maxillary sinus puncture and irrigation is a fundamental diagnostic and therapeutic procedure for otolaryngologists. The specific steps are as follows:

Mucosal Surface Anesthesia

Cotton swabs soaked with a decongestant (e.g., ephedrine or adrenaline) and a topical anesthetic (e.g., tetracaine) are used to anesthetize the nasal mucosa in the common meatus, inferior meatus, and middle meatus. The anesthesia typically lasts for 5–10 minutes.

Sinus Puncture

The thinnest section of the lateral wall of the inferior meatus, located 1–1.5 cm posterior to the anterior attachment of the inferior turbinate, serves as the insertion site. Under anterior rhinoscopic guidance, the tip of the maxillary sinus puncture needle is positioned at this site, with the bevel facing the lateral wall of the inferior meatus. The tip is directed toward the lateral corner of the ipsilateral eye. Gentle rotational pressure is applied to penetrate the bone. A "give" sensation indicates successful entry into the sinus cavity.

Figure 5 Maxillary sinus puncture and irrigation techniques

When puncturing the right maxillary sinus, the practitioner usually stabilizes the patient's head with the left hand and holds the needle with the thumb, index finger, and middle finger of the right hand while using the palm to support the needle's handle. For the left maxillary sinus, the hands are positioned oppositely. Alternatively, regardless of which side is being punctured, the left hand may always fix the head while the right hand holds the needle.

Irrigation

Once the sensation of entering a cavity ("give") is felt, the puncture needle should be stabilized. The needle core should then be removed, and a syringe attached to the needle. A check should be performed by pulling back the plunger to see if air or purulent fluid can be aspirated, indicating whether the tip of the needle is within the sinus. If purulent fluid is drawn, it should be sent for bacterial culture and drug sensitivity testing. After confirming that the needle tip is indeed within the sinus, physiological saline is slowly injected into the sinus cavity using the syringe to perform irrigation. If there is pus in the maxillary sinus, it will drain with the saline through the maxillary ostium and exit via the middle meatus.

The irrigation process should be repeated until no more purulent fluid is seen. If necessary, an antibiotic solution can be instilled into the sinus cavity after the pus has been rinsed out. Upon completion of the procedure, the puncture needle can be withdrawn. Under normal circumstances, minimal bleeding occurs from the puncture site and usually does not require any specific treatment. A cotton ball can be placed at the anterior nasal cavity to prevent minor bleeding.

For each irrigation session, detailed documentation of the characteristics of the purulent fluid should be made, including its consistency (mucoid-purulent, purulent, egg-drop-like, or rice-water-like), color, odor, and volume. If the condition is not resolved in one session, irrigation should be repeated weekly, depending on the patient's condition. To reduce the need for repeated needle punctures, a silicone catheter can be inserted into the sinus cavity through the needle channel during the first session. The external end of the catheter is then secured outside the anterior nasal cavity for continuous irrigation.

Although maxillary sinus puncture is a relatively simple technique, improper or careless operations can lead to complications. Potential complications include:

- Subcutaneous Emphysema or Infection in the Cheek Area: This occurs when the needle is inserted too far anteriorly, puncturing the cheek's soft tissues.

- Orbital Emphysema or Infection: This occurs if the needle is directed too superiorly and excessive force causes the puncture needle to enter the orbit via the roof of the maxillary sinus (orbital floor).

- Pterygopalatine Fossa Infection: This occurs if the needle passes through the posterior wall of the maxillary sinus into the pterygopalatine fossa.

- Air Embolism: This occurs if the puncture needle enters a large blood vessel, leading to the introduction of air.

To avoid complications, it is necessary to verify that the needle tip is properly located within the sinus cavity by aspirating to check for air/pus and ensuring there is no significant blood return, which could indicate that a blood vessel has been punctured.

Precautions for Maxillary Sinus Puncture and Irrigation

The puncture site and direction must be accurate, and the force applied should be moderate.

The procedure should stop immediately upon feeling the "give" sensation.

Air must never be injected through the needle.

If resistance is encountered when injecting saline, it suggests that the needle tip may not be within the sinus cavity. It could be embedded in the mucosa of the sinus wall, and repositioning the needle should be considered. If resistance persists, the procedure should be stopped. In some cases, resistance could also occur due to obstruction at the sinus ostium. If it can be confirmed that the needle tip is in the sinus cavity, gentle pressure may help clear the obstruction. However, if significant resistance continues, the procedure should be terminated.

During irrigation, close observation of the patient's eye and cheek areas is essential. If the patient complains of orbital pressure or pain, or if swelling in the cheek area is observed, the procedure should be stopped immediately.

If unexpected events such as syncope occur during the procedure, irrigation should be stopped at once, the needle withdrawn, and the patient placed in a supine position to be closely monitored with appropriate treatment provided as needed.

If persistent bleeding occurs after needle removal, pressure should be applied to the puncture site to achieve hemostasis.

If air embolism is suspected, the patient should be placed in a head-down and left-side-lying position to prevent the air embolism from entering cerebral or arterial vessels (e.g., coronary arteries). Oxygen therapy and other emergency measures should be provided promptly.

Systemic Treatment

General Treatment

Management is similar to that for upper respiratory tract infections and acute rhinitis, with adequate rest as necessary.

Antibiotic Therapy

Infections should be promptly controlled to prevent complications or chronic progression. When the causative pathogen is identified, antibiotics sensitive to the pathogen should be selected. If the pathogen is unknown, broad-spectrum antibiotics may be used. For confirmed anaerobic infections, metronidazole or tinidazole should be included in the treatment regimen.

Treatment for Atopic Conditions

Patients with allergic rhinitis, asthma, or other atopic conditions should receive systemic or local anti-allergic medications.

Management of Adjacent or Underlying Conditions

Treatment should be directed at resolving any adjacent infections, such as odontogenic maxillary sinusitis, or systemic diseases such as chronic conditions, addressing the underlying cause effectively.