Cerebrospinal rhinorrhea refers to cerebrospinal fluid (CSF) flowing into the nasal cavity through congenital or traumatic defects, fractures, or thinned areas in the bone at the anterior cranial fossa base, middle cranial fossa base, or other regions. Among various types of cerebrospinal rhinorrhea, traumatic cases are the most common. The cribriform plate of the ethmoid and the posterior wall of the frontal sinus have very thin bony structures that are closely connected to the dura mater. If both the bone and dura mater rupture simultaneously during trauma, cerebrospinal rhinorrhea occurs. Fractures of the middle cranial fossa base can also injure the roof of a large sphenoid sinus, leading to CSF leakage.

CSF leakage caused by fractures of the tegmen tympani of the middle ear or the bony portion of the Eustachian tube may reach the nasal cavity via the Eustachian tube, and this condition is known as cerebrospinal otorhinorrhea. Iatrogenic cerebrospinal rhinorrhea occurs due to surgical procedures, such as damage to the cribriform plate during middle turbinate resection or ethmoidectomy, or procedures like transsphenoidal resection of a pituitary tumor.

Non-traumatic cerebrospinal rhinorrhea can be categorized into cases caused by intracranial tumors or spontaneous factors based on etiology. Spontaneous cerebrospinal rhinorrhea is commonly associated with obesity, empty sella syndrome, increased intracranial pressure, and congenital bony defects at the cranial base.

Clinical Presentation

A clear, watery fluid intermittently or continuously flows out of the nasal cavity, most often unilaterally. Increased intracranial pressure, such as during head lowering or compression of both internal jugular veins, may result in increased fluid outflow. Cerebrospinal rhinorrhea typically occurs immediately after trauma, although in rare cases, delayed cerebrospinal leakage may manifest weeks or years later. Patients may experience reduced or lost sense of smell. About 20% of patients present with recurrent purulent meningitis as the primary symptom.

Diagnosis

Qualitative Analysis of Cerebrospinal Fluid

Glucose Quantification

Blood-tinged fluid flowing from the nasal cavity should raise suspicion of cerebrospinal rhinorrhea, especially when the center of staining on absorbent material appears red while the periphery is translucent, or when clear fluid flowing from the nostrils dries without forming crusts. Fluid volume may increase during movements like head lowering or jugular vein compression. Confirmatory diagnosis relies on glucose quantification, with a glucose level typically above 1.7 mmol/L. However, this can be affected by factors such as infection or elevated systemic blood sugar levels.

β-2 Transferrin Testing

β-2 transferrin is found exclusively in cerebrospinal fluid and perilymph in the inner ear but is absent in blood, nasal secretions, and external ear canal fluids. Immunofixation electrophoresis provides a highly sensitive and specific test, now regarded as the gold standard for CSF qualitative detection.

Leak Localization

Nasal Endoscopy

Nasal endoscopy, inserted through the anterior nares, is used for detailed examination of five specific regions: the superior nasal roof, posterior nasal roof, sphenoethmoidal recess, middle nasal meatus, and pharyngeal opening of the Eustachian tube. Compression of both internal jugular veins to increase intracranial pressure helps determine the source of CSF leakage into the nasal cavity. For example, if CSF originates from the nasal roof, the leak is in the cribriform plate; if it comes from the middle nasal meatus, the leak is in the frontal sinus; if from the sphenoethmoidal recess, the leak is in the sphenoid sinus; and if from the Eustachian tube, the leak is in the tympanic cavity or mastoid.

Imaging

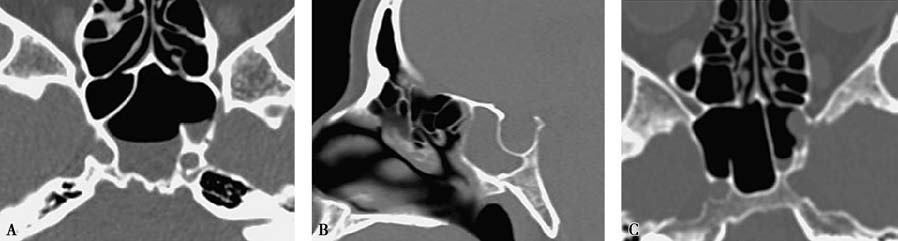

High-resolution thin-slice CT scans can reveal the location of bony defects or fractures and are commonly used for localizing CSF leaks. MRI cisternography may also be used for diagnostic localization of leaks.

Figure 1 Localization of cerebrospinal rhinorrhea leak on CT

A. CT image showing a bony defect in the lateral wall of the left sphenoid sinus.

B. CT image showing a bony defect at the roof of the ethmoid.

C. CT image showing a bony defect in the lateral wall of the left sphenoid sinus.

Surgical Exploration

When cerebrospinal rhinorrhea is confirmed but the precise site of leakage remains unclear, nasal endoscopic surgical exploration can be considered as an alternative option.

Treatment

Treatment is divided into conservative management and surgical intervention. Traumatic cerebrospinal rhinorrhea may sometimes resolve with conservative management, which includes measures to reduce intracranial pressure and prevent infection. These measures include maintaining a head-elevated position, restricting fluid intake and dietary salt, avoiding forceful coughing and nose blowing, and preventing constipation. Persistent cerebrospinal rhinorrhea can lead to bacterial meningitis. For cases that do not resolve with 2 to 4 weeks of conservative treatment or are accompanied by recurrent intracranial infections, surgical intervention becomes necessary.

Indications for Surgery

Surgical treatment is indicated for all cases of cerebrospinal rhinorrhea, including the following specific conditions:

- Cerebrospinal rhinorrhea accompanied by pneumocephalus (intracranial air), herniation of brain tissue, or intracranial foreign bodies;

- Cerebrospinal rhinorrhea caused by tumors;

- Cerebrospinal rhinorrhea associated with recurrent episodes of purulent meningitis.

Surgical Methods

The main approach is repair through the nasal cavity using nasal endoscopy. The principles of repair include precise localization, preparation of the graft bed, and a multilayered repair strategy. Layers are sequentially placed from the internal to the external surface, using materials such as fat, muscle, fascia, bone or cartilage, as well as free or pedicled flaps of periosteum or perichondrium. Commonly used materials include autologous septal mucosal flaps, free fascia lata, and artificial materials such as synthetic dura. Among these, the preparation of the graft bed and the selection of repair materials are critical.

For defects with a diameter of less than 1.0 cm, bone support is generally unnecessary. The repair materials can be placed and secured into the defect, acting as a "plug" that fits into the defect site. The natural pressure of intracranial pressure, along with mechanical forces such as downward traction (e.g., anchoring and pulling muscle tissue toward the nasal cavity after "bundling"), helps stabilize the plug at the defect site. This technique is referred to as the "bath-plug technique" in cerebrospinal rhinorrhea repair.