Facial paralysis can be classified into central and peripheral types. Paralysis resulting from lesions above the facial nerve nucleus is referred to as central facial paralysis, while lesions at or below the facial nerve nucleus lead to peripheral facial paralysis. This section focuses on peripheral facial paralysis.

Pathological Classification of Facial Nerve Injury

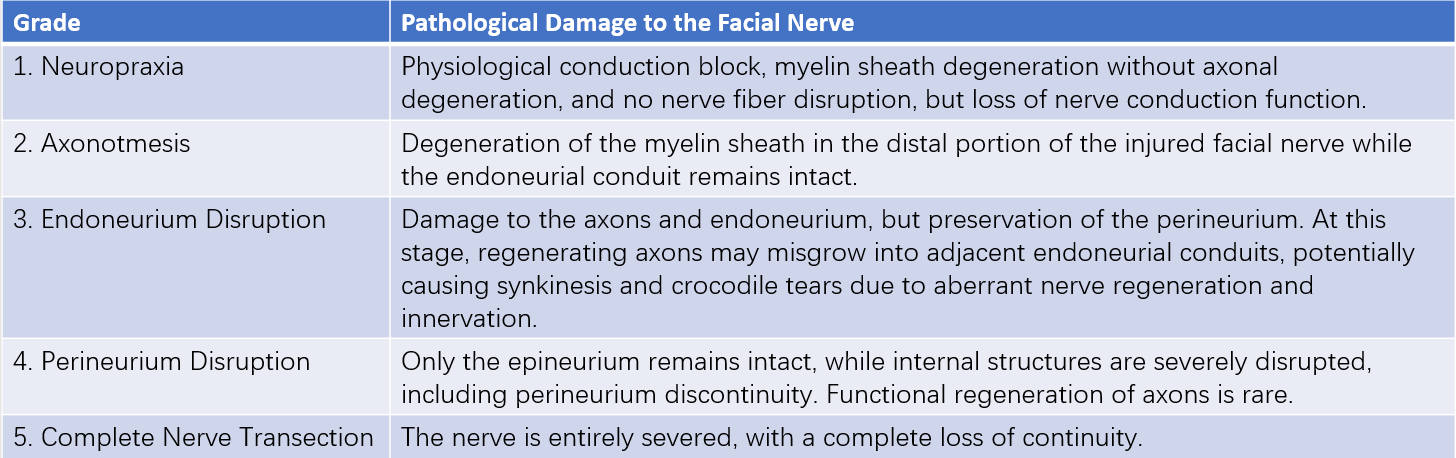

Sunderland classified facial nerve injuries into five grades based on the pathological changes: neuropraxia, axonotmesis, endoneurium disruption, perineurium disruption, and complete nerve transection.

Table 1 Sunderland pathological classification of facial nerve injury

Clinical Manifestations

Symptoms

Symptoms include:

- Facial asymmetry, including deviation of the mouth and difficulty closing the eyelid.

- Lacrimal gland dysfunction, including epiphora or alacrima. Damage to the facial nerve at or above the geniculate ganglion can involve the greater petrosal nerve, leading to these symptoms. Crocodile tears, a phenomenon where tearing occurs during eating due to misdirected nerve regeneration and innervation, can also develop.

- Altered taste sensations, caused by involvement of the chorda tympani nerve, resulting in taste abnormalities on the anterior two-thirds of the tongue on the affected side.

- Hyperacusis, resulting from dysfunction of the stapedius muscle branch of the facial nerve. The loss of the protective stapedius reflex against loud sounds can cause patients to become intolerant to loud auditory stimuli.

Signs

Static manifestations include loss of forehead wrinkles, a shallow or absent nasolabial fold, and widening of the palpebral fissure on the affected side.

Dynamic manifestations include an inability to raise the eyebrow, failure to close the eyelid, and upward and outward movement of the eyeball with exposed sclera when attempting to close the eye, known as "Bell's phenomenon." Smiling or baring teeth results in the mouth deviating toward the unaffected side, and air may escape from the cheek when attempting to puff it. Some patients might exhibit synkinesis, where movement of one branch of the facial nerve induces passive movement in muscles innervated by other branches.

Localization of Facial Nerve Injury

Imaging Studies

CT imaging can identify temporal bone fracture lines in most cases of trauma-induced facial paralysis and can reveal the site of injury to the facial nerve bony canal. MRI can detect facial nerve edema and degeneration and is helpful in ruling out mass lesions involving the facial nerve.

Schirmer's Test

Two 0.5-cm wide, 5-cm long strips of filter paper are folded at 5 mm from one end and placed in the conjunctival fornix for 5 minutes. A discrepancy in the length of wetted strips between the two eyes exceeding a twofold difference suggests damage to the facial nerve at or above the geniculate ganglion.

Taste Test

This test compares taste perception over the anterior two-thirds of the tongue on both sides. Loss of taste indicates facial nerve injury at or above the level of the chorda tympani nerve.

Stapedius Muscle Reflex

Absence of the reflex suggests injury at or above the level of the stapedius branch of the facial nerve.

Assessment of the Severity of Facial Nerve Damage

Neural Excitability Test (NET)

This test evaluates nerve degeneration and should be conducted after three days, as nerve fiber degeneration typically requires 1–3 days to develop. A bilateral difference greater than 2 mA indicates nerve degeneration. Values below 3.5 mA suggest possible recovery of facial nerve function, while values above 3.5 mA indicate severe degeneration with little likelihood of spontaneous recovery. A lack of response at 10 mA indicates complete denervation.

Electromyography (EMG) and Electroneurography (EnoG)

EMG assesses muscle activity by detecting fibrillation potentials, which appear approximately three weeks after denervation. The absence of detectable electrical activity indicates complete facial nerve paralysis. Electroneurography evaluates the facial nerve’s excitability; the extent of degeneration is expressed as the ratio of the amplitude of the affected side to the amplitude of the healthy side.

Assessment of Facial Paralysis Severity

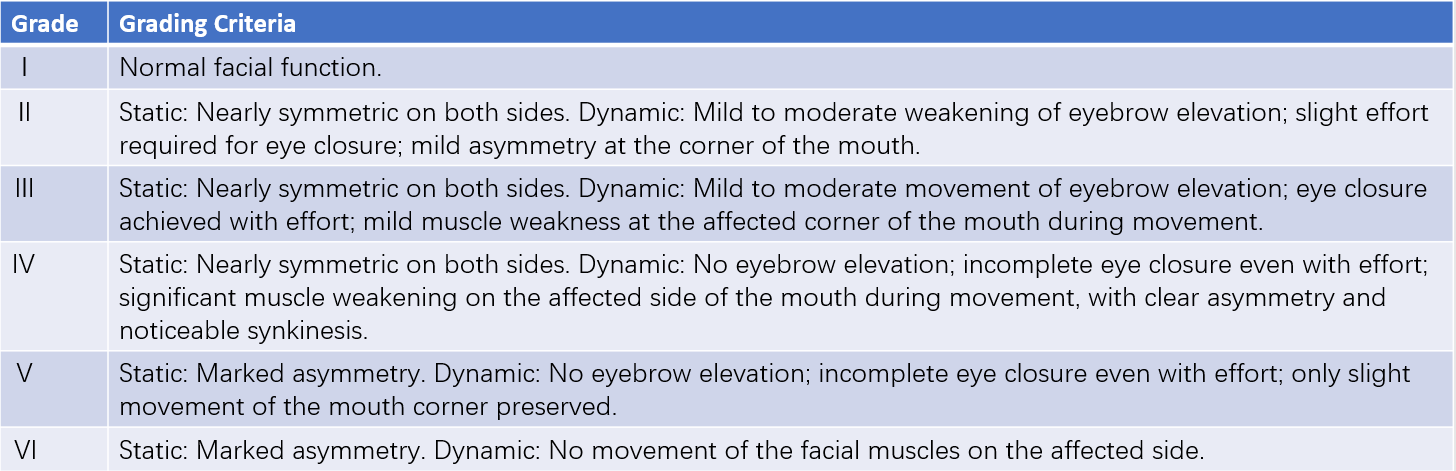

The House-Brackmann grading system is commonly used to evaluate the severity of facial paralysis. Based on Sunderland's pathological classification, the House-Brackmann system integrates clinical manifestations and prognosis to categorize facial nerve function into six grades.

Table 2 House-Brackmann facial nerve grading system

The Fisch scoring system uses a total score of 100 points, divided as follows: 20 points for static symmetry, 10 points for eyebrow elevation, 30 points for eye closure, 30 points for smiling or baring teeth, and 10 points for cheek puffing. Each category is assessed on four levels:

- 0%: Complete asymmetry on both sides of the face, with total paralysis and inability to move.

- 30%: Marked static asymmetry and unsatisfactory movement, closer to complete paralysis.

- 70%: Mild static asymmetry, relatively satisfactory movement but still not normal.

- 100%: Complete symmetry with normal facial movement.

Scores are calculated by multiplying the points of each category by the corresponding percentage, and the total score is determined by summing these values.

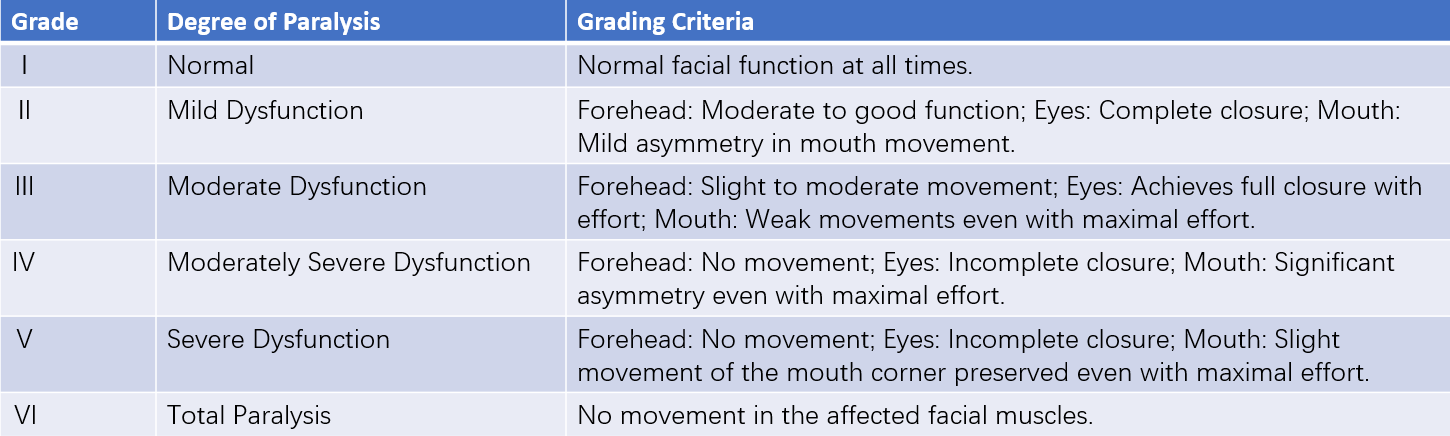

The facial nerve grading system established by the American Academy of Otolaryngology–Head and Neck Surgery (AAO-HNS) is also used to assess facial nerve function.

Table 3 AAO-HNS facial nerve function grading system

Common Types of Peripheral Facial Paralysis and Treatment Approaches

Bell's palsy is the most common cause of facial nerve paralysis, accounting for approximately 70% of all cases. Trauma is the second leading cause, contributing to about 10–23% of cases. Viral infections are responsible for 4.5–7% of cases, while cases caused by tumor formation comprise around 2.2–5%.

To be continued