Vertigo refers to a sensory illusion of motion or disorientation caused by the body's inability to accurately perceive its spatial positioning. The maintenance of balance requires sensory input from the vestibular system, proprioceptive system, and visual system, along with complex interactions and integration between the peripheral and central nervous systems. The vestibular system plays a dominant role in this process. In a stationary state, the vestibular receptors on both sides continuously send symmetrical and equivalent neural impulses to the ipsilateral vestibular nuclei. Simultaneously, information from the visual and proprioceptive systems is transmitted to the central nervous system. Through intricate neural reflexes, this process maintains the body's visual stability and postural balance. Any disruption to this symmetry or balance of information transmission, whether caused by physiological stimuli or pathological factors, can lead to balance disorders and, subjectively, the sensation of vertigo.

Classification

Vestibular Vertigo

Peripheral Vestibular Vertigo

Cochleo-vestibular Disorders:

- Within the labyrinth, e.g., Ménière’s disease.

- Ototoxicity caused by aminoglycosides.

Vestibular Disorders:

- Within the labyrinth, e.g., benign paroxysmal positional vertigo (BPPV).

- Outside the labyrinth, e.g., vestibular neuritis.

Central Vestibular Vertigo

This includes vascular, neoplastic, or traumatic conditions affecting the central vestibular system.

Non-Vestibular Vertigo

Conditions include:

- Ocular vertigo.

- Cervical vertigo.

- Circulatory system disorders.

- Hematologic diseases.

- Endocrine and metabolic diseases.

- Psychogenic vertigo.

Additionally, some diseases of the external and middle ear can also produce vertigo symptoms.

Examinations

The following assessments are typically performed:

- General physical examination.

- Otolaryngological examination.

- Neurological examination, including cranial nerve assessment, sensory system evaluation, and motor system testing.

- Mental health and psychological evaluation.

- Audiological assessments to aid in the localization of vertigo.

- Vestibular function tests, such as balance tests, coordination tests, oculomotor assessments, fistula tests, glycerol tests, vestibular-evoked myogenic potentials (VEMPs), head impulse tests, head-shake tests, and rotational chair tests.

- Ophthalmic evaluation to diagnose ocular vertigo.

- Cervical examination to evaluate cervical vertigo.

- Imaging investigations, such as CT, MRI, TCD (transcranial Doppler), and SPECT, to assess the conditions of the ears and intracranial structures.

- Electroencephalogram (EEG) tests.

- Laboratory testing.

Diagnosis

The diagnosis of vertigo should aim for precise localization, characterization, and determination of the underlying cause.

Medical History Collection and Analysis

Particular attention should be given to the following seven aspects:

Nature of Vertigo Episodes

Illusory Motion Vertigo:

- Rotatory vertigo (sensation of spinning).

- Translational vertigo (also known as displacement vertigo).

Imbalance, Disequilibrium, or Balance Disorders

These manifest as postural and gait abnormalities. Patients may experience a sensation of leaning or falling toward one side, instability while standing or walking, a staggering gait, or a sense of unsteadiness akin to intoxication.

Dizziness or Lightheadedness

Patients often struggle to clearly describe their discomfort, which may include sensations of lightheadedness, feeling unsteady, numbness inside the head, emptiness, head constriction, oppressive heaviness, or transient vision blackouts. These symptoms are more commonly associated with central vestibular disorders, such as ischemic cerebrovascular diseases, hyperventilation syndrome, or systemic illnesses affecting the vestibular system. However, vestibular disorders cannot be completely ruled out, as these may also represent a compensatory phase of vestibular dysfunction.

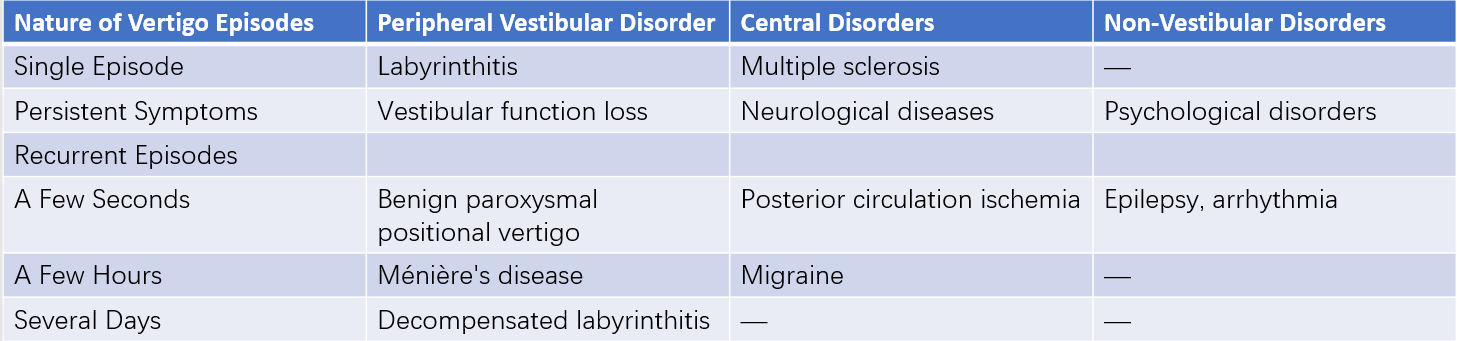

Temporal Characteristics of Vertigo Episodes

The time-related features, such as episodic or persistent nature, onset speed, and duration, vary according to the underlying cause.

Frequency and Duration of Vertigo Episodes

Vertigo lasting from a few seconds to about one minute is commonly associated with benign paroxysmal positional vertigo (BPPV).

Vertigo lasting several minutes to hours may indicate:

- Idiopathic endolymphatic hydrops (Ménière's disease).

- Secondary endolymphatic hydrops, such as otosyphilis, delayed endolymphatic hydrops, or Cogan syndrome.

Vertigo lasting for days to weeks is often seen in vestibular neuritis.

Vertigo with an unpredictable course may be caused by:

- Labyrinthine fistula.

- Inner ear injury, including non-penetrating trauma like labyrinthine concussion, penetrating injuries such as transverse temporal bone fractures involving the inner ear, barotrauma of the inner ear.

- Familial vestibulopathy.

- Bilateral vestibular injuries, such as those caused by aminoglycoside ototoxicity.

Context of Vertigo Episodes

The circumstances, such as specific body positions, loud sounds, or external pressure changes, under which vertigo occurs, provide critical information for accurate diagnosis.

Associated Symptoms

These may include cochlear symptoms (e.g., hearing loss, tinnitus), neurological symptoms (e.g., limb numbness, swallowing difficulties, motor impairments), and autonomic nervous system symptoms (e.g., nausea, vomiting). Attention should also be given to whether there is a loss of consciousness.

Precipitating Factors

Preceding events within days or hours of the onset, such as upper respiratory infections, emotional distress, or strenuous physical activity, should be investigated.

Past Medical History

Comprehensive information regarding past medical conditions across different systems should be obtained.

Assessment of Mental and Psychological State in Patients with Vertigo

This evaluation can aid in analyzing symptoms and formulating treatment plans.

Clinical Evaluation of Vertigo

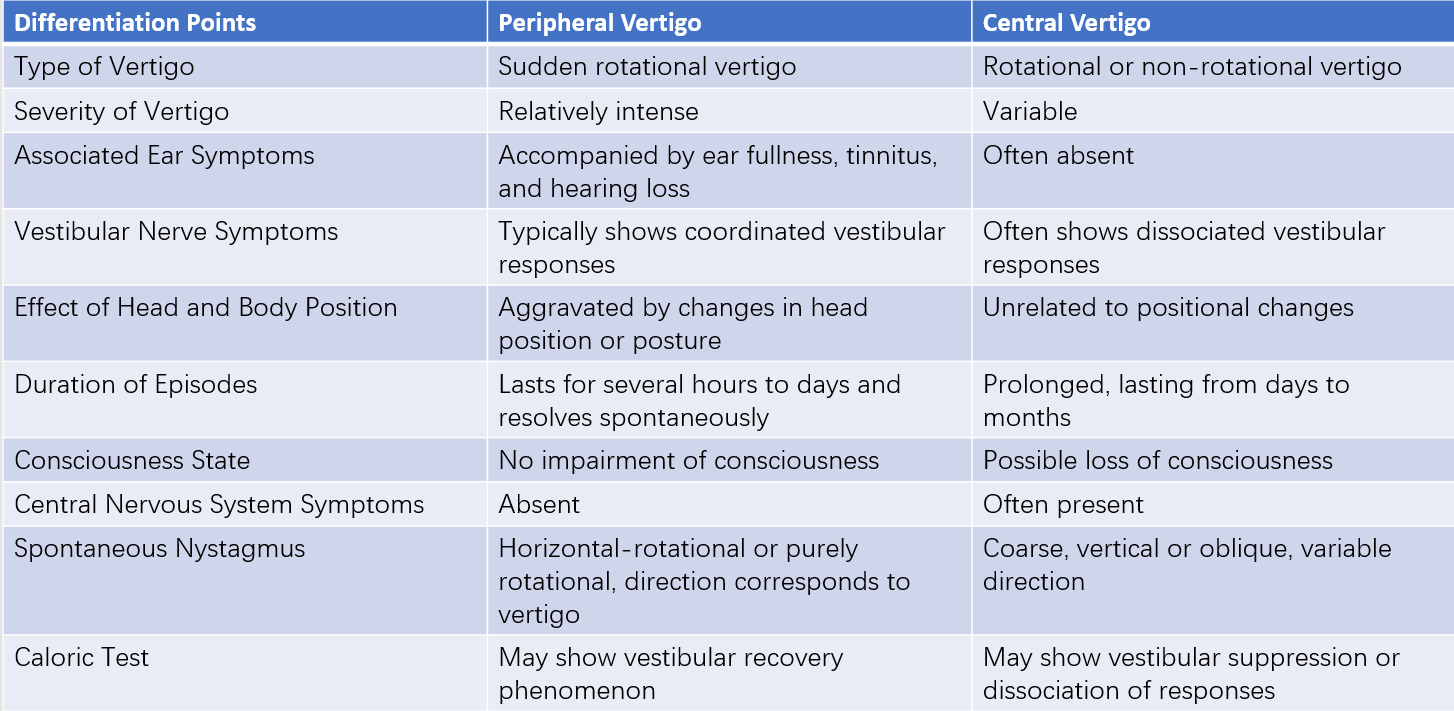

A comprehensive analysis of results from various clinical examinations is necessary to arrive at a diagnosis. General characteristics of peripheral and central vertigo include the following:

General Characteristics of Peripheral Vertigo

Peripheral vertigo is typically sudden in onset, rotational in nature, and of relatively short duration. It usually resolves spontaneously, often recurrent.

The intensity of vertigo is severe and may be accompanied by fluctuating tinnitus, hearing loss, autonomic symptoms (e.g., nausea, vomiting, pallor, sweating, hypotension). However, there is no loss of consciousness or other neurological symptoms.

Spontaneous nystagmus is rotational or rotational-horizontal. At the onset, nystagmus beats toward the affected side but later shifts to the healthy side. Vestibular responses are coordinated, and the directions of nystagmus and vertigo align. Tilting and directional pointing tests typically show consistent patterns opposite to each other. Spontaneous and induced vestibular reactions, as well as autonomic responses, are generally comparable.

Caloric testing may reveal vestibular recovery phenomena, where responses normalize after enhanced stimulation for weakened vestibular function. Significant directional preponderance is uncommon.

General Characteristics of Central Vertigo

Central vertigo can be either rotational or non-rotational and tends to have a longer duration (days, weeks, or even months) with variable intensity. The severity of vertigo is generally less pronounced, but it may progressively worsen. There is no direct correlation with head or body position changes.

Symptoms related to the ear may be absent, and other vestibular manifestations may not occur simultaneously. Autonomic responses are often disproportionate to the severity of vertigo.

Central vertigo is frequently accompanied by other symptoms, including cranial nerve deficits, and cerebellar or cortical impairments. Loss of consciousness may occur during episodes.

Spontaneous nystagmus is often coarse and may be vertical or oblique. It can also present as pendular nystagmus without slow or fast phases. The nystagmus may persist for extended periods, with varying intensity and direction, and sometimes exhibits bidirectional patterns.

Vestibular test responses often show dissociation. Spontaneous and induced responses may not correspond, and vestibular suppression phenomena may be observed (e.g., weak stimuli causing strong responses, while strong stimuli elicit weak responses).

Caloric testing may reveal dissociation between thermal responses, sometimes showing directional preponderance toward the affected side.

Differential Diagnosis

The most critical aspect is distinguishing between central and peripheral vertigo.

Differentiation is based on the general characteristics of peripheral and central vertigo.

Table 1 General characteristics of peripheral versus central vertigo

Differentiation is also based on the features of vertigo episodes and the course of the disease.

Table 2 Differential diagnosis based on vertigo episode characteristics and course

Treatment

Treatment encompasses symptomatic management (reference can be made to the treatment of Ménière's disease), etiological treatment, and vestibular rehabilitation therapy, among other methods. In recent years, vestibular rehabilitation therapy has become an important approach in the management of vertigo.