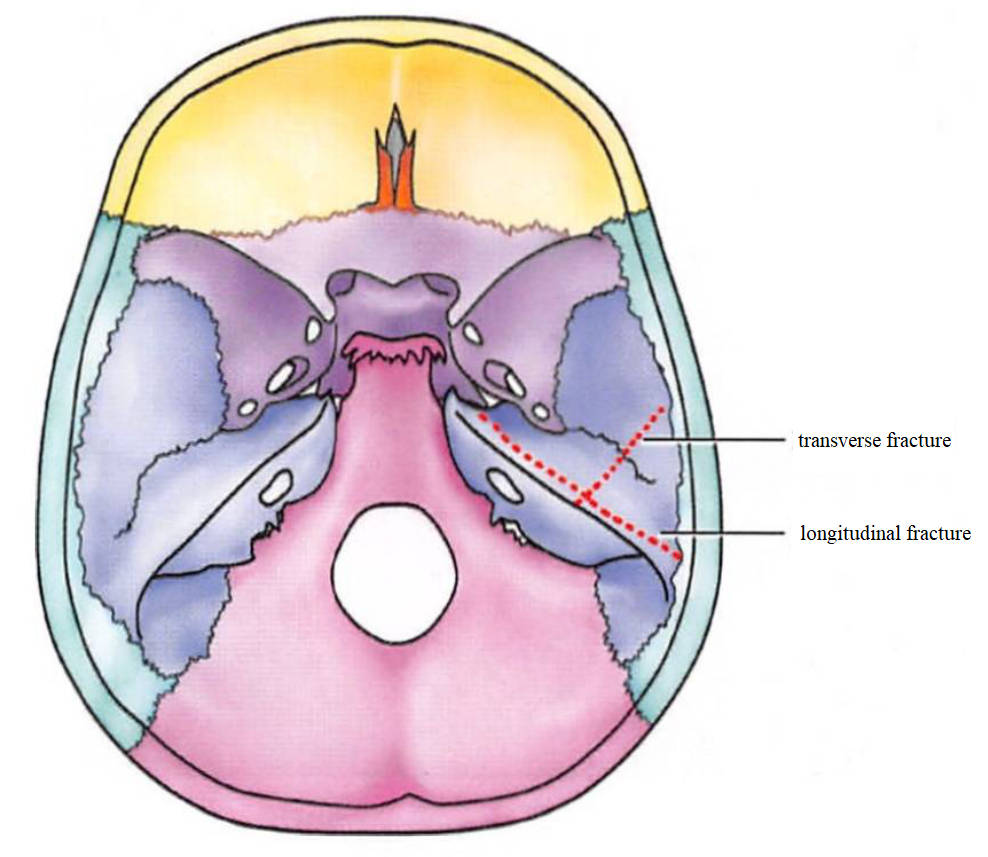

Temporal bone fractures are often caused by motor vehicle accidents, trauma to the temporal or occipital region, or falls. These fractures are frequently accompanied by intracranial injuries or damage to other organs such as the chest or abdomen. Approximately 1/3 of skull base fractures involve the petrous portion of the temporal bone. Among the petrous, squamous, and mastoid portions of the temporal bone, fractures of the petrous portion are the most common. Due to the thinner bone at the junction of the petrous and squamous portions, fractures are more likely to involve the middle ear than the inner ear. Temporal bone fractures may affect the middle ear, inner ear, and facial nerve. Based on the relationship between the fracture line and the long axis of the petrous bone, temporal bone fractures are classified into longitudinal fractures, transverse fractures, mixed fractures, and petrous apex fractures. Occasionally, multiple types of fractures may coexist.

Clinical Manifestations

Longitudinal Fracture

Longitudinal fracture is the most common type, accounting for 70% - 80% of cases, typically caused by trauma to the temporal or parietal region. The fracture line runs parallel to the long axis of the petrous bone, often originating from the squamous portion of the temporal bone, passing through the posterior superior wall of the external auditory canal and the tegmen tympani, extending along the carotid canal to the foramen spinosum or foramen lacerum at the middle cranial fossa. Since the fracture line often passes anterior or lateral to the bony labyrinth, the inner ear is rarely affected. Middle ear structures are often involved, with symptoms such as otorrhagia, conductive hearing loss, or mixed hearing loss. About 20% of cases develop facial paralysis, which often resolves gradually. If the dura mater is torn, cerebrospinal fluid (CSF) leakage may occur. Longitudinal fractures may occur bilaterally and occasionally involve the temporomandibular joint.

Transverse Fracture

Transverse fracture is less common, accounting for about 20% of cases, and typically caused by trauma to the occipital region. The fracture line is perpendicular to the long axis of the petrous bone, often originating from the occipital bone near the foramen magnum, crossing the petrous pyramid to the middle cranial fossa. Some fractures pass through the hypoglossal canal or other foramina in the petrous portion (e.g., the jugular foramen), and in rare cases, through the internal auditory canal and the labyrinth to the vicinity of the foramen lacerum or foramen spinosum. Since the fracture line may pass through the internal auditory canal or bony labyrinth, it may disrupt the medial wall of the tympanic cavity, vestibular window, or cochlear window, leading to symptoms such as sensorineural hearing loss, vertigo, spontaneous nystagmus, facial paralysis, and hemotympanum. Facial paralysis occurs in approximately 50% of cases and is less likely to recover.

Figure 1 Schematic diagram of temporal bone fracture

The dashed line is the fracture line

Mixed Fractures

Mixed fractures are very rare, often resulting from multiple skull fractures, involving both longitudinal and transverse fractures of the temporal bone. This may lead to tympano-labyrinthine fractures, causing symptoms of both middle and inner ear involvement.

Petrous Apex Fracture

Petrous apex fracture is extremely rare, and may damage cranial nerves II-VI, leading to symptoms such as decreased vision, narrowing of the palpebral fissure, ptosis, pupil dilation, impaired eye movement, diplopia, and strabismus. Other symptoms may include trigeminal neuralgia or facial sensory disturbances. Petrous apex fracture may also damage the internal carotid artery, causing fatal hemorrhage. These fractures should be differentiated from brainstem injuries and brain herniation.

Complications

All types of temporal bone fractures may be accompanied by meningeal injuries, resulting in CSF leakage. CSF leaking through a ruptured tympanic membrane and exiting via the external auditory canal is called CSF otorrhea. If the tympanic membrane remains intact, CSF may leak through the eustachian tube and exit via the nose, resulting in CSF rhinorrhea. If CSF leaks simultaneously from both the external auditory canal and nasal cavity, it is referred to as CSF otorhinorrhea.

Treatment

Temporal bone fractures are often associated with traumatic brain injuries. If symptoms of increased intracranial pressure, cranial nerve deficits, or severe hemorrhage from the ear or nose are present, treatment should be coordinated with neurosurgeons to stabilize the patient. The primary focus should be on addressing life-threatening issues, such as maintaining airway patency (tracheostomy may be necessary), controlling hemorrhage, and administering fluids or blood transfusions to prevent hypovolemic shock and maintain normal circulatory function. Once the patient is stabilized, detailed examinations, including cranial CT and neurological assessments, should be conducted.

Prompt administration of antibiotics is essential to prevent intracranial or ear infections. The ear should be disinfected thoroughly, and any blood clots or debris in the external auditory canal should be carefully removed under sterile conditions if the patient's overall condition permits. In case of CSF otorrhea, the external auditory canal should not be packed; instead, a sterile cotton ball can be placed at the canal opening. If possible, the patient should be positioned with the head elevated or in a semi-recumbent position. Most CSF leaks resolve spontaneously. If leakage persists beyond 2 - 3 weeks, surgical repair using temporalis muscle or fascia to cover the dural defect may be required to control the leak.

For peripheral facial paralysis caused by transverse temporal bone fractures, surgical decompression of the facial nerve should be performed as early as possible, provided the patient's condition allows. If conservative treatment for 2 - 6 weeks is ineffective and the patient's overall condition is stable, facial nerve decompression surgery may be performed. In the later stages, tympanoplasty or facial nerve surgery may be considered to address residual tympanic membrane perforations, ossicular chain disruptions, conductive hearing loss, or facial nerve paralysis.

Prognosis

Longitudinal fractures have the best prognosis. Conductive hearing loss can often be restored through tympanoplasty or tympanic membrane repair. Transverse fractures have a poor prognosis, with often irreversible sensorineural hearing loss. Vestibular function loss may gradually compensate over time. After head trauma, fracture lines may persist, and if a middle ear infection occurs, meningitis may develop. Pediatric patients generally have a better prognosis compared to adults.