Patent ductus arteriosus (PDA) accounts for about 10% of congenital heart disease cases. During fetal development, the ductus arteriosus functions as an essential pathway for blood circulation. After birth, functional closure usually occurs within approximately 15 hours, with 80% achieving anatomical closure by 3 months of age. Complete anatomical closure is typically achieved by the age of 1 year. If the ductus remains open, it is referred to as patent ductus arteriosus. PDA mostly occurs as an isolated anomaly, but in 10% of cases, it is associated with other cardiovascular defects, such as coarctation of the aorta, ventricular septal defect, or pulmonary stenosis. In certain congenital heart defects, such as pulmonary atresia, a patent ductus arteriosus becomes a vital channel for survival, and closure can result in fatal outcomes.

The risk of PDA is higher in premature infants due to underdeveloped ductal smooth muscle and a reduced response of the smooth muscle to oxygen tension compared to full-term infants. PDA occurs in 20% of preterm infants and is often accompanied by respiratory distress syndrome.

Pathological Anatomy

The size, length, and shape of the patent ductus arteriosus vary and are typically classified into three types:

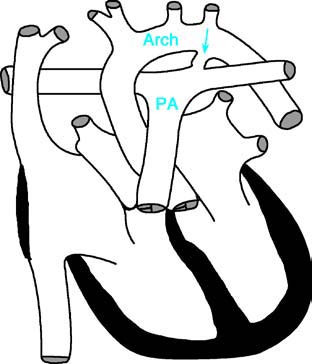

Figure 1 Schematic diagram of patent ductus arteriosus

PA—Pulmonary Artery; Arch—Aortic Arch. The arrow indicates the location of the patent ductus arteriosus.

Tubular Type

The ductus, connecting the aorta and pulmonary artery, has a uniform diameter throughout its length.

Funnel Type

The ductus is wide at its origin near the aorta and becomes progressively narrower toward the pulmonary artery end. This is the most common clinical presentation.

Window Type

The ductus is very short but often has a relatively large diameter.

Pathophysiology

The pathological and physiological changes caused by PDA are primarily determined by the volume of blood shunted through the ductus, which depends on the duct's diameter and the pressure difference between the aorta and the pulmonary artery. Since the aortic pressure exceeds pulmonary artery pressure during both systole and diastole, there is continuous left-to-right shunting of blood through the ductus. This results in a significant increase in pulmonary circulation, as well as increased blood flow to the left atrium, left ventricle, and ascending aorta. The left heart experiences an increased workload, and cardiac output may reach two to four times the normal level.

Excessive pulmonary blood flow may lead to dynamic pulmonary hypertension. Over time, the ductus undergoes constriction, thickening of its walls, and sclerosis, resulting in obstructive pulmonary hypertension. This condition places an excessive systolic load on the right ventricle, leading to right ventricular hypertrophy. When pulmonary artery pressure exceeds aortic pressure, the left-to-right shunting decreases significantly or ceases altogether, resulting in a reversal of blood flow. Blood from the pulmonary artery then flows retrograde into the descending aorta. This manifests as differential cyanosis, where the lower half of the body appears cyanotic, the left upper limb may show mild cyanosis, and the right upper limb remains normal.

Clinical Manifestations

In cases with a small patent ductus arteriosus, symptoms may be absent. With larger ductal openings, particularly in infancy, repeated respiratory tract infections, congestive heart failure, and symptoms such as coughing, dyspnea, feeding difficulties, failure to gain weight, and growth retardation are common. Significant left-to-right shunting may also cause precordial fullness or protrusion of the chest.

A continuous "machinery-like" murmur can be heard over the second intercostal space along the left sternal border, encompassing both systole and diastole, and is often accompanied by a palpable thrill. This murmur may radiate to the left clavicular area, left supraclavicular area, neck, and back. When pulmonary vascular resistance is elevated, the diastolic component of the murmur may diminish or disappear. In the presence of pulmonary hypertension or heart failure, only a systolic murmur may be audible. During the neonatal period, due to higher pulmonary artery pressure and minimal pressure difference between the aorta and pulmonary artery during diastole, the murmur may be limited to systole.

Significant left-to-right shunting may also result in a relative mitral stenosis murmur, producing a short mid-diastolic murmur heard at the cardiac apex, especially in cases of a large PDA. An accentuated second heart sound is often audible over the pulmonary valve area. A widened pulse pressure may occur due to reduced diastolic pressure, leading to the appearance of peripheral vascular signs such as a "water hammer" pulse, pistol-shot sounds, and capillary pulsations visible in the nail beds.

In preterm infants with PDA, prominent peripheral arterial pulsations, a systolic murmur (occasionally continuous), noticeable precordial pulsations, hepatomegaly, tachypnea, and a predisposition to respiratory failure are often observed.

Auxiliary Examinations

X-ray Examination

In cases of a small patent ductus arteriosus (PDA), the cardiac silhouette may appear normal. When there is a large shunt, the cardiothoracic ratio increases, the left ventricle becomes enlarged, and the cardiac apex extends downward. The left atrium may also be mildly enlarged. Pulmonary vasculature becomes prominent, with a marked pulmonary artery segment and engorged hilar vessels. Fluoroscopic imaging shows enhanced pulsation of the left ventricle and aorta. In the presence of pulmonary hypertension, the main pulmonary artery trunk and its branches are dilated, while the distal pulmonary arterial vessels in the lung fields appear narrowed. Signs of left ventricular enlargement and hypertrophy may also be visible. The aortic arch appears normal or slightly prominent. In infants with heart failure, pulmonary congestion may be observed.

Figure 2 Chest X-ray of patent ductus arteriosus (Frontal view)

Electrocardiography (ECG) Examination

In cases with a significant shunt, varying degrees of left ventricular hypertrophy may be observed, accompanied by left axis deviation and occasionally left atrial enlargement. When pulmonary artery pressure is markedly elevated, both the left and right ventricles may show hypertrophic changes, and in the later stages, right ventricular hypertrophy may be the predominant finding.

Echocardiography

Two-dimensional echocardiography can directly detect the patent ductus arteriosus. Pulsed Doppler imaging at the ductal opening reveals a characteristic continuous turbulent flow spectrum during both systole and diastole. Color Doppler imaging superimposed on the structural images shows red flow signals originating from the descending aorta and streaming along the outer wall of the pulmonary artery through the patent ductus. In cases of severe pulmonary hypertension, when pulmonary pressure exceeds aortic pressure, blue flow signals can be observed as blood flows retrogradely from the pulmonary artery into the descending aorta through the patent ductus.

Cardiac Catheterization

Cardiac catheterization is performed when pulmonary vascular resistance is increased or if there is suspicion of associated cardiovascular anomalies. This method reveals a higher oxygen saturation in the pulmonary artery compared to the right ventricle. Occasionally, the catheter may pass from the pulmonary artery into the descending aorta through the patent ductus. Retrograde aortography plays a valuable diagnostic role in complex cases; injecting contrast into the aortic root demonstrates simultaneous filling of both the aorta and pulmonary artery, clearly showing the patent ductus arteriosus.

Treatment

To prevent infective endocarditis, cardiac dysfunction, and pulmonary hypertension, timely surgical or interventional closure of the patent ductus arteriosus is generally recommended. Interventional methods are now preferred in most cases, with closure devices like coil embolization or occluder devices, such as the Amplatzer device, being commonly used. In certain conditions, including complete transposition of the great arteries, pulmonary atresia, tricuspid atresia, or severe pulmonary stenosis, the ductus arteriosus serves as a lifeline to maintain the patient's survival. In these cases, prostaglandin E2 infusion or stent placement is necessary to keep the ductus arteriosus open. Surgical intervention is considered for patients who are not candidates for interventional procedures or those with associated anomalies requiring correction.

Management of PDA in preterm infants depends on the shunt size and the presence of respiratory distress syndrome. For symptomatic cases, anti-congestive therapy is required, and indomethacin is used within the first week of life. However, approximately 10% of preterm infants may still require surgical closure.

Prognosis

The surgical outcomes for patent ductus arteriosus are highly effective, with very low operative mortality rates. Small shunts, particularly those detected in the neonatal or early infancy period, often resolve spontaneously by 3 months of age. In such cases, no special treatment is typically required, and regular follow-up is considered sufficient.