Bronchiectasis primarily refers to a heterogeneous group of diseases characterized by irreversible bronchial dilatation due to bronchial wall destruction and thickening. This condition results from congenital bronchial underdevelopment or other underlying causes, compounded by acute and chronic respiratory tract infections and bronchial obstruction. Clinically, it is mainly characterized by recurrent or chronic cough, production of purulent sputum, hemoptysis, recurrent infections, and abnormal imaging findings.

Etiology and Pathogenesis

Bronchiectasis in children differs from that in adults, as the majority of pediatric cases have identifiable underlying causes. Studies have shown that 63%–86% of pediatric bronchiectasis cases are associated with underlying diseases. The primary causes include:

Infections

Lower respiratory tract infections are the most common cause of bronchiectasis in Chinese children. These infections include those caused by bacteria (such as Bordetella pertussis, Streptococcus pneumoniae, and Mycobacterium tuberculosis), Mycoplasma pneumoniae, and viruses (such as measles virus and adenovirus).

Aspiration

Tracheobronchial foreign body aspiration is frequently observed in children under the age of three. Other causes include chronic pulmonary aspiration due to conditions such as tracheoesophageal fistula, swallowing dysfunction, and gastroesophageal reflux.

Congenital Bronchial and Pulmonary Malformations

These include conditions such as tracheomalacia, bronchial stenosis, bronchogenic cysts, and tracheobronchomegaly.

Primary Immunodeficiency Disorders

Persistent or recurrent infections, especially multi-site or opportunistic infections, may suggest primary immunodeficiency disorders. The most common form involves B lymphocyte deficiency, including common variable immunodeficiency disorder, agammaglobulinemia, and IgA deficiency. Other forms include hyper-IgE syndrome, hyper-IgM syndrome, combined immunodeficiency, and chronic granulomatous disease.

Primary Ciliary Dyskinesia (PCD)

PCD is a hereditary disorder affecting multiple organs and is mainly characterized by chronic cough, chronic sinusitis, otitis media, and bronchiectasis.

Cystic Fibrosis (CF)

CF, a recessive autosomal genetic disorder, is the most common cause in Western countries but is rare in Asian populations. In addition to respiratory symptoms, CF is associated with multi-systemic involvement, including digestive, endocrine, and reproductive systems.

Systemic Diseases

Bronchiectasis is present in 1%–3% of patients with systemic diseases such as rheumatoid arthritis, systemic lupus erythematosus, Sjögren's syndrome, ankylosing spondylitis, and relapsing polychondritis.

Other Causes

Examples include allergic bronchopulmonary aspergillosis and α1-antitrypsin deficiency.

Cases in which modern diagnostic techniques fail to identify a cause are categorized as idiopathic bronchiectasis.

The pathogenesis of bronchiectasis is not yet fully understood. Current understanding suggests that reduced pulmonary mucociliary clearance, persistent or recurrent respiratory infections and inflammation, and bronchial obstruction are fundamental factors. These factors are interrelated, forming a vicious cycle that progressively destroys the bronchial wall's smooth muscle, elastic fibers, and even cartilage. This weakens the structural integrity of the bronchial wall, eventually resulting in irreversible bronchial dilatation.

Pathology

The primary pathological findings include dilation and wall destruction of segmental or subsegmental bronchi. Elastic tissue, smooth muscle, and cartilage in the bronchial wall may be replaced by fibrous tissue, resulting in three distinct forms of bronchiectasis:

- Cylindrical bronchodilation.

- Saccular bronchodilation.

- Irregular bronchodilation.

Microscopic findings may reveal bronchial inflammation, fibrosis, bronchial ulceration, squamous metaplasia, and mucus gland hyperplasia. Adjacent lung parenchyma may show fibrosis, emphysema, bronchopneumonia, and atelectasis. Inflammation can lead to increased blood vessels in the bronchial wall, accompanied by corresponding bronchial artery dilation and anastomoses between bronchial and pulmonary arteries. Capillary dilation may form aneurysms, leading to recurrent hemoptysis.

Clinical Manifestations

The typical clinical manifestations include chronic cough and the production of sputum, occurring most often in the morning upon waking or when changing position. Sputum may vary in quantity and often contains thick purulent material. During acute exacerbations, symptoms may worsen, with increased coughing, sputum production, fever, and hemoptysis. Patients frequently seek medical attention due to recurrent pulmonary infections.

Physical findings depend on the extent of the disease and the severity of bronchial dilatation. Mild bronchiectasis may present without significant physical signs. Severe cases or those with secondary infections may exhibit persistent moist rales over the affected areas, which temporarily resolve after coughing up sputum. Long-standing cases may show clubbing of the fingers and toes, malnutrition, and delayed growth.

Supplementary Examinations

Imaging Studies

Chest X-Ray

A chest X-ray may show no abnormalities in some children with bronchiectasis, limiting its diagnostic utility. Typical findings include the "tram-track sign," irregular ring-shaped radiolucent shadows, or a honeycomb pattern.

High-Resolution Computed Tomography (HRCT) of the Chest

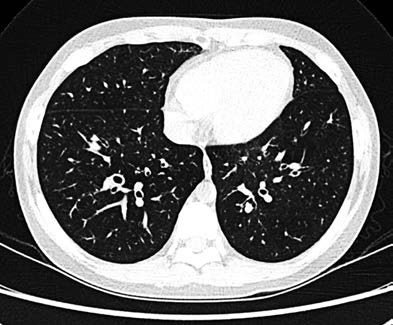

HRCT has become the primary diagnostic method for bronchiectasis due to its non-invasive nature, ease of use, and ability to directly visualize the morphology, distribution, and location of bronchiectasis. Key findings include:

- Bronchial lumen diameter enlargement exceeding 1.5 times the normal size, with wall thickening.

- A bronchial artery-to-accompanying pulmonary artery diameter ratio > 0.8 (in the absence of pulmonary hypertension), creating the "signet ring sign" in cross-section.

- Loss of the normal tapering pattern of airways from central to peripheral, with a "railroad track" appearance in longitudinal sections. Bronchial shadows may also be seen within 1 cm beneath the chest wall.

HRCT can further display airway wall thickening (internal diameter < 80% of the outer diameter), small airway dilation, and mucus plugs, commonly referred to as the "tree-in-bud sign."

Figure 1 Chest CT of bronchiectasis illustrating the "signet ring sign"

Laboratory Tests

Complete Blood Count

Acute exacerbations of bronchiectasis caused by bacterial infections may present elevated leukocyte counts, increased neutrophil percentage, and higher C-reactive protein levels.

Immunologic Evaluation

Immunoglobulin levels, lymphocyte subpopulations, specific antibody titers, and human immunodeficiency virus antibody tests are conducted to assist in diagnosing primary or secondary immunodeficiency disorders.

Pathogen Identification

Qualified sputum or bronchoalveolar lavage fluid (BALF) specimens should be submitted for smear, culture, and other pathogen detection methods.

Pulmonary Function Tests

Pulmonary function tests are significant for evaluating bronchiectasis. Routine pulmonary ventilation function tests are recommended during initial assessment in children aged five years or older. Children with bronchiectasis may exhibit obstructive ventilatory dysfunction, restrictive ventilatory dysfunction, or relatively normal pulmonary function.

Bronchoscopy

Bronchoscopy has become an important tool for identifying underlying causes of bronchiectasis in children. It allows for the direct observation of conditions such as foreign body aspiration, tracheobronchomalacia, and airway malformations. It also facilitates the collection of BALF for microbiological and cytological examinations.

Additional Tests

Sinus nitric oxide measurement, ciliary transmission electron microscopy, and high-speed video microscopy analysis are utilized for suspected primary ciliary dyskinesia (PCD). Genetic testing may also be conducted when necessary.

Sweat chloride tests and genetic testing are performed for suspected cystic fibrosis (CF).

Tests such as rheumatoid factor, antinuclear antibodies, and antineutrophil cytoplasmic antibodies are conducted when systemic diseases are suspected.

Swallowing function tests, including videofluoroscopic swallowing studies, fiberoptic endoscopic evaluations, or radionuclide salivary scans, are conducted for suspected pulmonary aspiration.

Selective testing of Aspergillus fumigatus-specific IgE/IgG and serum precipitating antibodies can be performed for suspected allergic bronchopulmonary aspergillosis.

Diagnosis and Differential Diagnosis

A diagnosis of bronchiectasis is made based on the presence of chronic cough, purulent sputum, recurrent hemoptysis, a history of repeated pulmonary infections, persistent moist crackles on lung auscultation, and HRCT findings confirming bronchial dilation.

Since identifying the underlying cause of bronchiectasis is critical for effective treatment in children, the diagnosis should not stop at confirming the presence of bronchiectasis. It is essential to perform differential diagnoses and further investigations to identify any potential underlying conditions.

Treatment

The primary objectives in the treatment of bronchiectasis are to clear airway secretions, reduce the frequency of respiratory infections, maintain stable lung function, and improve the quality of life for affected children.

Clearing Airway Secretions

Airway clearance techniques, such as postural drainage, chest percussion, high-frequency chest wall oscillation vests, forced expiration techniques, positive end-expiratory pressure ventilation, and the use of active breathing trainers, form the foundation of effective treatment for bronchiectasis. These methods help clear airway secretions, improve airway patency, alleviate clinical symptoms, reduce inflammation, and prevent further airway damage. Physical sputum drainage can be combined with nebulized inhalation of normal saline, hypertonic saline, or mucolytic agents such as N-acetylcysteine to thin and facilitate the expulsion of mucus.

Infection Control

In cases of acute exacerbation, antibacterial agents may be considered. Sputum cultures should be routinely sent prior to treatment, and antibiotic selection should be guided by culture and drug sensitivity results. Empirical antibiotic therapy should, however, be initiated while awaiting culture results.

Immunomodulators

Macrolides with 14-membered or 15-membered lactone rings exhibit both antibacterial and anti-inflammatory properties that directly target the pathogenesis of bronchiectasis. For patients with frequent acute exacerbations, low-dose macrolides such as erythromycin or azithromycin may be used for a treatment course of at least six months.

Other Pharmacological Treatments

Oral expectorants and mucolytic agents can be used to enhance mucus clearance. Bronchodilators may improve airflow limitation and facilitate the removal of secretions, making them suitable for children with airway hyperreactivity and reversible airflow obstruction. Currently, there is no evidence from clinical trials to support the routine use of inhaled corticosteroids for anti-inflammatory treatment.

Treatment of Underlying Conditions

In cases where the underlying condition involves antibody deficiencies, replacement therapy with immunoglobulin may be administered.

Surgical Intervention

Surgery may be considered for patients with localized bronchiectasis who continue to experience recurrent infections or massive hemoptysis despite medical treatment. For children with severe and extensive pulmonary disease or significant clinical symptoms, lung transplantation may be an option.

Management and Monitoring

Educational materials should be provided to caregivers and children, focusing on the daily management of bronchiectasis as well as the treatment and management of acute exacerbations. Key aspects include introducing airway clearance techniques, medications, and infection control strategies. For cases with a clear underlying cause, explanations regarding the primary disease and its potential impact on acute exacerbation should be provided. This helps caregivers recognize early signs of acute exacerbation and seek medical attention promptly. Unsupervised use of antibiotics by children is not recommended. A personalized follow-up and monitoring plan should be developed.

Prevention

The use of pneumococcal and influenza vaccines may help prevent or reduce the frequency of acute exacerbations. Immunomodulators may offer some benefit in alleviating symptoms and reducing exacerbations. Reducing exposure to tobacco and engaging in rehabilitation exercises can contribute to maintaining lung function.