Pneumonia refers to inflammation of the terminal airways, alveoli, and pulmonary interstitium caused by various pathogens or other factors, such as amniotic fluid aspiration, allergic reactions, or immune damage. Among infectious diseases, pneumonia caused by microbial pathogens is one of the most common, occurring year-round but more frequently during the cold seasons of winter and spring. Premature infants, low birth weight infants, malnourished children, and those with underlying conditions such as congenital airway structural abnormalities, congenital heart disease, immunodeficiency, or neuromuscular diseases are more susceptible to pneumonia. The primary clinical manifestations include fever, cough, and fixed medium and fine moist rales in the lungs. Severe cases may present with tachypnea, respiratory distress, and involvement of extrapulmonary systems, including circulatory, neurological, and digestive systems, causing corresponding clinical features.

Classification

There is no universally accepted classification system for pneumonia; however, the following categorizations are commonly used:

Classification by Anatomy

Bronchopneumonia

This is caused by pathogens invading through the bronchi, leading to inflammation of the bronchioles, terminal bronchioles, and alveoli. It is the most common type of pneumonia in children, particularly in infants and toddlers under 2 years old. On chest X-rays, irregular patchy shadows following the lung markings may be seen, with indistinct and shallow margins. No consolidation is typically observed, and the lower lobes of the lungs are often affected.

Lobar Pneumonia

This occurs when pathogens cause inflammation initially in the alveoli and then spread via the pores of Kohn to adjacent alveoli, resulting in the involvement of part of or an entire lung segment or lobe. Chest X-rays show consolidated shadows in the affected lung lobe or segment.

Interstitial Pneumonia

This type primarily involves inflammation of the pulmonary interstitium, including the bronchial walls and peribronchial tissues. Chest X-rays reveal increased, thickened, and rigid lung markings on one or both sides, with diffuse reticular or ground-glass opacity.

Classification by Etiology

Viral Pneumonia

In children under 5 years of age, respiratory syncytial virus (RSV) is the most common causative agent, followed by influenza virus, human metapneumovirus, rhinovirus, and adenovirus (ADV). In children older than 5 years, influenza virus, ADV, RSV, and rhinovirus are more common.

Bacterial Pneumonia

This type is caused by pathogens such as Streptococcus pneumoniae (SP), Staphylococcus aureus (SA), Klebsiella pneumoniae (KP), Haemophilus influenzae (HI), Escherichia coli (E. coli), and Legionella species.

Mycoplasma Pneumonia

This is caused by Mycoplasma pneumoniae.

Chlamydia Pneumonia

This is typically caused by Chlamydia trachomatis (CT), Chlamydia pneumoniae (CP), and Chlamydia psittaci. CT and CP are more commonly seen.

Parasitic Pneumonia

This is caused by conditions such as pulmonary hydatidosis, pulmonary toxoplasmosis, pulmonary schistosomiasis, and pulmonary nematodiasis.

Fungal Pneumonia

This is caused by pathogens such as Candida albicans, Aspergillus spp., Histoplasma capsulatum, Cryptococcus spp., and Pneumocystis jirovecii. This type is more commonly seen in individuals with immunodeficiency or those on long-term immunosuppressive or antimicrobial therapy.

Non-Infectious Pneumonia

This includes conditions such as aspiration pneumonia, hypostatic pneumonia, and eosinophilic pneumonia (allergic pneumonia).

Classification by Disease Course

Acute Pneumonia

Disease course lasts less than 1 month.

Protracted Pneumonia

Disease course lasts between 1 and 3 months.

Chronic Pneumonia

Disease course exceeds 3 months.

Classification by Severity

Mild Cases

This presents with minimal involvement of extrapulmonary systems, with no systemic toxic manifestations.

Severe Cases

Respiratory failure is present, along with functional impairment in other systems. Acid-base imbalance, water and electrolyte disturbances, and significant systemic toxic symptoms may occur, potentially becoming life-threatening.

Classification by Location of Onset

Community-Acquired Pneumonia (CAP)

This is an infectious pneumonia acquired outside the hospital in previously healthy children, including cases caused by pathogens with a clear incubation period that manifest during the incubation period after hospitalization.

Hospital-Acquired Pneumonia (HAP)

Also known as nosocomial pneumonia, this refers to infectious pneumonia that was not present or incubating at the time of admission but develops 48 hours or more after hospitalization. HAP also includes pneumonia acquired during hospitalization but manifests within 48 hours after discharge.

In clinical practice, if the causative pathogen is clearly identified, classification by etiology is preferred as it guides treatment. If the causative agent is unclear, classification by anatomy or another system may be used.

Etiology and Pathogenesis

Respiratory viruses are common pathogens causing pneumonia in children, and age often serves as a predictor of the likely causative pathogen. In young children, approximately 50% of pneumonia cases are caused by viruses, including respiratory syncytial virus (RSV), influenza virus, adenovirus, parainfluenza virus, and rhinovirus. In older children, bacterial and Mycoplasma infections are more frequently encountered. Common Gram-positive bacteria include Streptococcus pneumoniae, Staphylococcus aureus, and group A Streptococcus (GAS). Common Gram-negative bacteria include Haemophilus influenzae, Moraxella catarrhalis, Escherichia coli, and Klebsiella pneumoniae.

The occurrence of pneumonia depends on both the pathogen and host factors. Pneumonia develops when the pathogen load is high, the pathogen's virulence is strong, and/or the local and systemic immune defenses of the respiratory system are compromised. Once pathogens reach the lower respiratory tract and begin to replicate, they invade the host or release toxins, leading to lung tissue damage.

Pathology and Pathophysiology

The main pathological changes involve congestion, edema, and inflammatory cell infiltration in lung tissue. The alveolar spaces fill with exudates, spreading through the pores of Kohn into adjacent tissues, forming patchy inflammatory foci. When these foci coalesce, they may involve multiple pulmonary lobules or more extensive regions. Inflammatory changes in small and terminal bronchi can lead to partial or complete obstruction of the airways, resulting in pulmonary hyperinflation or atelectasis. Pathological changes vary depending on the causative pathogen: bacterial pneumonia primarily affects lung parenchyma, while viral pneumonia mainly involves the interstitial tissue but can also affect alveoli. Clinically, bronchopneumonia and interstitial pneumonia frequently coexist.

The primary pathophysiological changes in pneumonia arise from inflammation of the bronchi and alveoli, leading to ventilation and gas exchange impairments. This causes hypoxia and carbon dioxide retention, which can result in a range of functional abnormalities in both pulmonary and extrapulmonary systems.

Clinical Manifestations

The onset is often acute, with a preceding upper respiratory tract infection for several days. The main clinical manifestations include fever, cough, sputum production, and fixed medium and fine moist rales in the lungs.

Main Symptoms

Fever

The fever pattern is variable and often irregular, but it may present as remittent fever or persistent high fever. In neonates or severely malnourished children, body temperature may not rise or may even be below normal.

Cough

Frequent cough is observed, initially as a dry, irritating cough. During the acute phase, coughing may decrease, while productive cough develops during the recovery phase.

Tachypnea and Respiratory Distress

These symptoms may occur in cases with extensive lung involvement.

Systemic Symptoms

Symptoms such as lethargy, altered consciousness, irritability, poor appetite, vomiting, and diarrhea are common.

Physical Signs

In early stages or mild cases, pulmonary signs may not be prominent. In severe cases, findings such as increased respiratory rate, nasal flaring, intercostal retractions, and cyanosis (around the lips, nasolabial folds, and peripheral extremities) may be observed. Early lung auscultation findings may include coarse or diminished breath sounds. As the disease progresses, fixed medium and fine moist rales can be detected, most commonly in the lower parts of the back and paraspinal areas, becoming more evident at the end of deep inspiration. Percussion of the chest is typically normal but may show signs of consolidation if the lesions coalesce.

Auxiliary Examinations

Peripheral Blood Tests

White Blood Cell Count

In bacterial pneumonia, white blood cell (WBC) count is often elevated with an increase in neutrophils and a left shift. Toxic granulation may be observed in the cytoplasm. In viral pneumonia, the WBC count is typically normal or slightly decreased, although it may occasionally be elevated with lymphocytosis or the presence of atypical lymphocytes.

C-Reactive Protein (CRP)

Serum CRP levels are often elevated in bacterial infections but remain less significantly increased in non-bacterial infections.

Procalcitonin (PCT)

PCT levels are elevated in bacterial infections and rapidly decrease with effective antibiotic treatment.

Chest X-Ray

In early stages, pulmonary markings may appear increased, and lung transparency is reduced. Later, the bilateral lower lung fields and middle zones may show variable-sized small nodular or patchy opacities, or consolidation involving lung segments or lobes. Findings such as pulmonary hyperinflation and atelectasis may also be observed. In cases with accompanying empyema, early changes include blunted costophrenic angles on the affected side, while large effusions may appear with meniscus-shaped opacities and a mediastinal and cardiac shift toward the unaffected side. In pneumothorax with empyema, air-fluid levels may be visible in the affected pleural cavity. Pulmonary cysts manifest as thin-walled air-filled lesions without fluid levels. Pulmonary abscesses may present as rounded lesions with thickened walls and surrounding inflammatory infiltration. Interstitial pneumonia primarily shows increased, thickened, and stiffened pulmonary markings, with diffuse reticulonodular opacities or ground-glass opacities. In clinically stable children with suspected pneumonia who can receive outpatient treatment, routine chest X-ray is generally unnecessary. Chest CT scans are useful in cases where pneumonia is highly suspected but not confirmed on X-ray, when identifying the location of inflammation is challenging, or if airway and pulmonary abnormalities or certain severe complications are suspected. However, routine use of CT scans and lateral chest X-rays is not advised. Children who have clinically recovered from pneumonia and are in good general condition do not require repeated chest X-rays.

Pathogen Identification

Pathogen testing may not be required for mild pneumonia. In severe pneumonia, pathogen testing should ideally be conducted before initiating antibiotic therapy to guide treatment. Specimens such as nasopharyngeal swabs, oropharyngeal swabs, nasopharyngeal aspirates, sputum, tracheal aspirates, bronchoalveolar lavage fluid, blood, pleural effusions, tissue samples, or focal aspiration samples may be collected for pathogen testing. Common methods include:

Microscopic Examination of Stained Smears

Staining methods such as hexamine silver staining, acid-fast staining, and Gram staining applied to qualified lower respiratory tract specimens are used to detect fungi, mycobacteria, and certain bacteria.

Pathogen Culture

This is primarily used for bacterial detection, with specific culture media tailored to different pathogens. Results can be combined with in vitro susceptibility testing to guide treatment. Viral isolation and culture have limited clinical application due to technical challenges and long processing times.

Pathogen-Specific Antigen Detection

This method uses known pathogen-specific antibodies to detect corresponding antigens in patients, employing techniques such as latex agglutination, colloidal gold immunochromatography, and direct immunofluorescence assays. This approach facilitates rapid screening for viruses like influenza, RSV, adenovirus, and novel coronaviruses, as well as for bacteria (Streptococcus pneumoniae) and fungi (Aspergillus, Candida, and Cryptococcus).

Pathogen-Specific Antibody Testing: Employing immunological techniques, this method uses known pathogen antigens to detect corresponding antibodies in patients, thereby diagnosing infections. Tests include complement fixation, enzyme-linked immunosorbent assay (ELISA), particle agglutination, and fluorescent antibody testing. This method is commonly used to identify viruses, Mycoplasma, Chlamydia, and Legionella.

Pathogen Nucleic Acid Detection

This includes genome-sequence-dependent methods like polymerase chain reaction (PCR), which uses specific primers to amplify and detect pathogen nucleic acids. It also includes genome-sequence-independent approaches like metagenomic sequencing, which does not require pre-designed primers and utilizes high-throughput sequencing of microbial genomes in samples, followed by comparison with database sequences to identify pathogens.

Diagnosis

Diagnosing pneumonia is relatively straightforward. Diagnosis can be made based on the presence of fever, cough, and sputum production, along with physical findings such as medium and fine moist rales on lung auscultation and/or chest imaging changes indicative of pneumonia.

Once pneumonia is confirmed, further evaluation of disease severity and identification of the causative pathogen are required. For children with recurrent pneumonia episodes, identifying underlying conditions or risk factors that lead to recurrent infections is essential. These may include primary or secondary immunodeficiencies, structural or developmental abnormalities of the respiratory tract, bronchial foreign bodies, congenital heart disease, malnutrition, prematurity, allergies, and environmental factors.

Severity Assessment

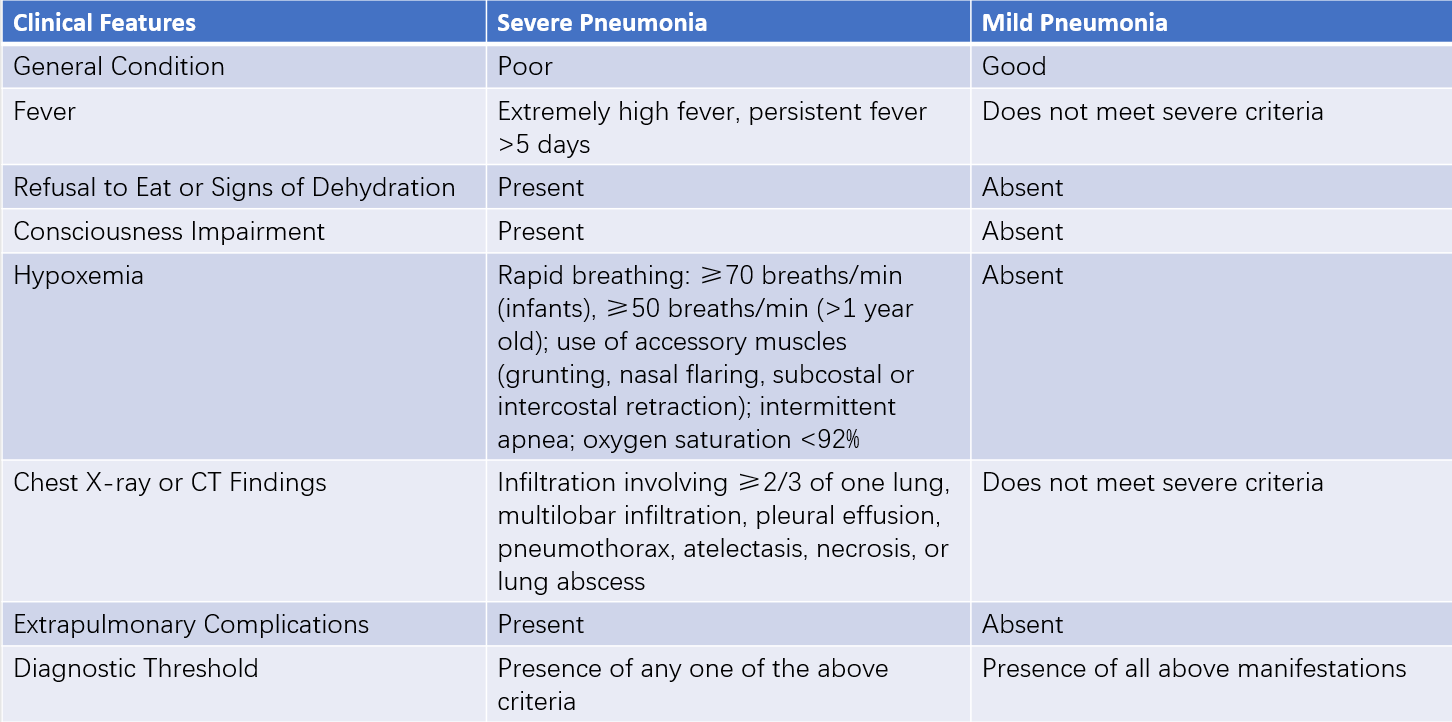

Severe pneumonia is characterized by significant ventilation/gas exchange impairment or pulmonary and extrapulmonary complications. Severe pneumonia has a high mortality rate and can lead to long-term sequelae, making early recognition crucial. Due to economic and cultural variations, standardized criteria for pediatric severe pneumonia are not universally established. At outpatient or resource-limited primary care settings, WHO's simplified criteria for identifying severe pneumonia in children are often recommended. Severe pneumonia is suggested by the presence of any of the following: chest wall indrawing, nasal flaring, or grunting during breathing. Features such as central cyanosis, severe respiratory distress, refusal to feed, signs of dehydration, or altered consciousness (e.g., lethargy, coma, seizures) indicate very severe pneumonia. In hospitalized patients or regions with better healthcare resources, the assessment of severe pneumonia should also consider the extent of lung involvement, the presence of hypoxemia, and manifestations of pulmonary and extrapulmonary complications.

Table 1 Diagnostic criteria for severe pneumonia in children

Differential Diagnosis

Acute Bronchitis

Acute bronchitis typically presents without fever or only low-grade fever. The overall condition is usually good, with cough being the predominant symptom. Lung auscultation findings include dry and moist rales, which are often not fixed and may change with coughing. Chest X-rays show increased and disorganized pulmonary markings. If differentiation is challenging, treatment may proceed as for pneumonia.

Foreign Body in the Airway

A history of foreign body aspiration, sudden onset of choking and coughing, and findings such as atelectasis and pulmonary hyperinflation are helpful for differentiation. When the condition becomes prolonged or secondary infection occurs, the presentation may resemble pneumonia or involve concurrent pneumonia, necessitating careful distinction.

Bronchial Asthma

Pediatric asthma may present without obvious wheezing episodes, with persistent cough as the main symptom. Chest X-rays may show increased and disorganized pulmonary markings, along with hyperinflation, making it easily confusable with pneumonia. The presence of atopic features in the child, along with findings from pulmonary function tests, bronchial provocation tests, and bronchodilator response tests, facilitates differentiation.

Pulmonary Tuberculosis

Tuberculosis is often associated with a history of contact with an infected individual and a positive tuberculin skin test. Chest X-rays revealing tuberculous lesions in the lungs also assist in differentiation. Miliary tuberculosis can present with tachypnea and cyanosis, closely resembling pneumonia. However, pulmonary rales may be less prominent.

Complications

Complications are rare in cases where early and appropriate treatment is provided. Delayed diagnosis or infections caused by virulent pathogens may, however, lead to complications. Pulmonary complications include pleural effusion, empyema, pneumothorax, pyopneumothorax, pulmonary bullae, lung abscess, necrotizing pneumonia, bronchopleural fistula, acute respiratory distress syndrome (ARDS), and acute respiratory failure. Extrapulmonary complications include sepsis, septic shock, disseminated intravascular coagulation (DIC), and persistent infection foci (e.g., pericarditis, endocarditis, meningitis, brain abscess, septic arthritis, and osteomyelitis).

Empyema

Empyema presents clinically with persistent high fever and worsening respiratory distress. On the affected side, reduced respiratory movement, diminished tactile fremitus, dullness to percussion, and weakened breath sounds may be observed. Tubular breath sounds may occasionally be heard above the affected area. With significant empyema, intercostal spaces on the affected side may become full, and the mediastinum and trachea may shift to the healthy side. Chest X-rays (in an upright position) show blunted costophrenic angles or meniscus-shaped opacities on the affected side. Thoracentesis reveals purulent fluid.

Pyopneumothorax

Pyopneumothorax occurs when a peripheral lung abscess ruptures and communicates with the alveoli or small bronchi. Clinical manifestations include sudden worsening of respiratory distress, severe coughing, restlessness, and cyanosis. Percussion may reveal hyperresonance above the fluid level, while auscultation reveals reduced or absent breath sounds. If the bronchial rupture forms a one-way valve, trapping air and leading to tension pneumothorax, it can be life-threatening, requiring urgent intervention. Chest X-rays in an upright position show air-fluid levels in the pleural space.

Pulmonary Bullae

Pulmonary bullae form due to post-inflammatory edema and narrowing of small bronchi, leading to valvular partial obstruction. This results in more air entering than exiting or complete air trapping, causing alveolar overdistension and rupture. Bullae may range from single to multiple lesions. Small bullae are asymptomatic, while larger ones may cause respiratory distress. X-rays reveal thin-walled cavities.

Lung Abscess

Lung abscesses are cavity lesions caused by suppurative infections leading to necrosis of lung parenchyma and abscess formation. Common pathogens include aerobic pyogenic bacteria such as Staphylococcus aureus and Klebsiella pneumoniae. Abscesses may extend to the pleura or rupture into the pleural cavity, causing empyema. The onset is usually insidious, with symptoms such as fever, malaise, anorexia, and weight loss. During the acute phase, features resembling bacterial pneumonia may be noted, including cough (often with hemoptysis), purulent foul-smelling sputum after approximately 10 days in untreated cases, respiratory distress, high fever, and chest pain. There may be significant leukocytosis. Chest X-rays show round opacities, and if in communication with a bronchus, fluid levels within the abscess may be observed, surrounded by inflammatory infiltration. Lung abscesses can be solitary or multiple. Post-treatment, residual fibrotic strands may remain on imaging.

These four complications are most commonly associated with Staphylococcus aureus pneumonia, drug-resistant Streptococcus pneumoniae, and pneumonia due to certain Gram-negative bacilli.

Treatment

A comprehensive treatment approach is implemented, with the principles focusing on improving ventilation, controlling infection, symptomatic management, and prevention and treatment of complications.

Symptomatic Treatment and Care

Ensuring adequate air circulation in the room, with a temperature of 18–20°C and humidity at 60%, is essential. Nutrient-rich diets are provided, and for critically ill children who have difficulty eating, enteral nutrition can be supplemented with parenteral nutrition. Changing body positions frequently reduces pulmonary congestion and promotes inflammation absorption. Isolation is maintained to prevent cross-infection.

Symptomatic treatments such as antipyretics, expectorants, and bronchodilators are utilized as needed. For high fever, antipyretics like oral paracetamol or ibuprofen are used. In cases of agitation, chloral hydrate or phenobarbital at 5 mg/kg via intramuscular injection may be administered. Severe coughing and wheezing may be addressed with nebulized glucocorticoids combined with bronchodilators. Attention to water and electrolyte replacement is crucial, with correction of acidosis and electrolyte imbalances. Appropriate fluid supplementation is also helpful for airway humidification, though infusion rates are carefully monitored to avoid overloading the heart.

Antimicrobial Treatment

Antibacterial Therapy

Antibacterial drugs are used in confirmed bacterial infections or secondary bacterial infections following viral infections.

Principles

Effectiveness and safety are prioritized when selecting antibacterial drugs.

Before administration, suitable respiratory secretions or blood samples are collected for bacterial culture and susceptibility testing to guide therapy. In the absence of culture results, empirical use of appropriate antibiotics is considered.

The selected drug should achieve high concentrations in lung tissue.

Oral antibacterial agents may suffice for mild cases, whereas severe pneumonia or cases involving vomiting and poor gastrointestinal absorption require parenteral antibacterial therapy.

Proper dosage and an appropriate treatment duration are prescribed.

Intravenous combination therapy is often recommended for patients with severe illness.

Antibiotic Choice Depending on Pathogen

Streptococcus pneumoniae

Penicillin or amoxicillin is the first choice for penicillin-sensitive strains. High-dose penicillin or amoxicillin is preferred for intermediate strains. For penicillin-resistant strains or patients with lobar consolidation, necrotizing pneumonia, or lung abscess, ceftriaxone or cefotaxime is the first-line choice, with vancomycin or linezolid as alternatives.

Staphylococcus aureus

For methicillin-sensitive strains, oxacillin or cloxacillin is preferred. For resistant strains, vancomycin is the first choice, with options including teicoplanin, linezolid, or fusidic acid combinations.

Haemophilus influenzae

First-line options include amoxicillin/clavulanic acid or ampicillin/sulbactam.

Escherichia coli and Klebsiella pneumoniae

For non-ESBL-producing strains, third- or fourth-generation cephalosporins, piperacillin, cefoperazone/sulbactam, cephamycin, or piperacillin/tazobactam are recommended. For ESBL-producing strains with mild to moderate infections, cefoperazone/sulbactam or piperacillin/tazobactam is preferred. Severe infections or cases unresponsive to other antibiotics may require carbapenems such as ertapenem, imipenem, or meropenem.

Mycoplasma pneumoniae and Chlamydia pneumoniae

Macrolide antibiotics, including azithromycin, erythromycin, and clarithromycin, are first-line treatments.

Treatment Duration

Antibiotics are typically continued for 3–5 days after defervescence and significant improvement in general and respiratory symptoms. Factors such as the specific pathogen, disease severity, and the presence of bacteremia influence the treatment duration. For example, Streptococcus pneumoniae pneumonia generally requires 7–10 days, while M. pneumoniae or C. pneumoniae infections average 10–14 days. Severe cases may require longer courses. For Staphylococcus aureus pneumonia, antibiotics may be stopped 2–3 weeks after the temperature normalizes, with an overall treatment duration of at least 6 weeks.

Antiviral Therapy

Few antiviral drugs are definitively effective, and their side effects significantly limit clinical application.

Ribavirin has in vitro efficacy against RSV, but its effectiveness for RSV-associated CAP remains debated. Due to concerns regarding efficacy and safety, it is not generally recommended for RSV pneumonia.

Interferon-alpha (IFN-α) is rarely used in clinical settings and involves treatment courses lasting 5–7 days, with nebulized administration as an alternative. However, its efficacy is controversial.

For influenza infection, oseltamivir (Tamiflu) may be used orally.

Respiratory Support

Airway Management

Clearing nasal crusts, nasal secretions, and sputum as needed maintains airway patency and improves ventilation. Airway humidification promotes mucus clearance and is essential, especially for patients undergoing mechanical ventilation, where attention is given to airway humidification, position changes, and chest percussion.

Oxygen Therapy

Oxygen supplementation is indicated in cases of hypoxia, such as agitation and cyanosis, or when arterial oxygen partial pressure is below 60 mmHg. Common methods include nasal cannula oxygen delivery with humidified oxygen at flow rates of 0.5–1 L/min and oxygen concentrations below 40%. In neonates or young infants, oxygen masks, oxygen hoods, or nasal prongs can be used, with mask oxygen flow rates at 2–4 L/min and oxygen concentrations at 50–60%.

Assisted Ventilation

Non-invasive ventilation or intubation with mechanical ventilation is utilized when normal blood oxygen levels cannot be maintained or hypercapnia persists under standard oxygen therapy.

Extracorporeal Membrane Oxygenation (ECMO)

For severe pneumonia with acute respiratory distress syndrome (ARDS) unresponsive to mechanical ventilation and other treatments, ECMO may be considered.

Management of Complications

Management of conditions such as sepsis, septic shock, meningitis, and pericarditis can be referenced in relevant chapters of this book.

Pleural Effusion and Pneumothorax

Large pleural effusions and pneumothorax are typically managed with closed thoracic drainage. In cases of empyema accompanied by lung consolidation, particularly in necrotizing pneumonia, early use of thoracoscopy for debridement is not advised.

Lung Resection

In necrotizing pneumonia complicated by pyopneumothorax, pulmonary lesions generally regain normal function. However, when deformities occur or complications arise that are difficult to manage medically, such as bronchopleural fistula or tension pneumothorax, lobectomy may be considered.

Glucocorticoids

Routine glucocorticoid use is not recommended. Short-term glucocorticoid therapy may be considered under the following circumstances: severe or refractory Mycoplasma pneumonia, severe adenovirus pneumonia, Streptococcus pyogenes (Group A streptococcus) pneumonia, refractory septic shock, viral encephalopathy, acute respiratory distress syndrome (ARDS), or asthma or wheezing associated with the above conditions. Medications such as methylprednisolone (1–2 mg/[kg·day]), hydrocortisone sodium succinate (5–10 mg/[kg·day]), or dexamethasone (0.1–0.3 mg/[kg·day]) can be administered via intravenous infusion.

Intravenous Immunoglobulin (IVIG)

Routine use of IVIG is not recommended. Its application may be considered in the following circumstances: certain severe bacterial pneumonias, such as CA-MRSA (community-associated Staphylococcus aureus pneumonia); Mycoplasma pneumonia with extrapulmonary manifestations such as erythema multiforme or encephalitis; immunodeficiency, particularly cases of hypogammaglobulinemia or agammaglobulinemia; and severe adenovirus pneumonia.

Bronchoscopy and Related Interventions

Routine bronchoscopy is not recommended. Its application may be considered under the following circumstances: the need to clear airway obstruction or atelectasis caused by inflammatory secretions or necrotic material, as in severe or refractory Mycoplasma pneumonia, adenovirus pneumonia, or influenza pneumonia with excessive airway secretions or the formation of obstructive casts and mucosal necrosis; situations where conventional treatments are ineffective, requiring investigation of airway conditions such as tracheomalacia, stenosis, foreign body obstruction, tuberculosis lesions, or alveolar hemorrhaging, with bronchoalveolar lavage also providing material for etiological analysis; and diagnosis of airway injury following infection, for structural changes in the airway caused by refractory Mycoplasma pneumonia, adenovirus pneumonia, measles pneumonia, or influenza pneumonia (e.g., cartilage damage or airway obstruction), with bronchoscopy aiding both diagnosis and treatment.

Prevention

General Prevention

Measures to enhance physical fitness, reduce passive smoking, ensure adequate indoor ventilation, and actively address malnutrition, anemia, and rickets are crucial. Attention to hand hygiene and prevention of cross-infection are also important.

Targeted Prevention

Vaccination against common bacterial and viral pathogens can effectively reduce the incidence of pneumonia in children. Available vaccines include pneumococcal vaccines, Haemophilus influenzae type b conjugate vaccines, and influenza vaccines.