Inflammatory bowel disease (IBD) refers to a group of nonspecific chronic inflammatory diseases of the gastrointestinal tract with unknown causes. It includes ulcerative colitis (UC), Crohn's disease (CD), and indeterminate colitis (IC). In recent years, the incidence of IBD in children has been increasing, significantly affecting growth, development, and quality of life. IBD, particularly Crohn's disease, often has its onset during adolescence, with statistics showing that approximately 20%–30% of IBD cases are diagnosed during childhood.

The clinical presentation of pediatric IBD primarily involves the form of de novo disease, with younger onset age being associated with more severe symptoms. IBD diagnosed in children under the age of six represents a distinct subtype of IBD. Its clinical phenotype and genetic characteristics differ from those of later-onset IBD and are termed very early-onset IBD (VEO-IBD). VEO-IBD tends to be more severe, exhibits poor response to conventional therapies, and is often accompanied by primary immunodeficiency disorders.

Etiology and Pathogenesis

The etiology and pathogenesis of IBD remain incompletely understood, but the condition is widely regarded as the result of a complex interplay of genetic, environmental, and immune factors. The current understanding is that its pathogenesis is mediated by an excessive intestinal mucosal immune response, triggered by factors such as infection, ultimately leading to mucosal damage in genetically susceptible individuals.

Genetic Factors

Epidemiological data indicate significant racial and familial clustering of IBD cases, with marked variations in incidence rates across different ethnic groups. Caucasians have the highest incidence rates, followed by African Americans, while Asian populations exhibit the lowest rates. Advances in immunology, genetics, and molecular biology, particularly the application of genome-wide association studies (GWAS) and gene chip techniques, have identified an increasing number of genetic loci associated with susceptibility to IBD. VEO-IBD is often a monogenic disease or a rare polygenic disorder linked to immune system abnormalities. For instance, VEO-IBD is commonly associated with deficiencies in IL10RA and IL10RB, where intestinal inflammation arises directly from defects in immune responses.

Environmental Factors

Children in industrialized countries exhibit higher incidence rates of IBD compared to those in non-industrialized countries. The incidence is also higher among urban children compared to those in rural and mountainous areas. Asian immigrants who relocate to Europe and North America, as well as their descendants, demonstrate a marked increase in IBD susceptibility. These trends suggest that various environmental factors such as infections, smoking, diet, gut microbiota, and climate of residence may play roles in the pathogenesis of IBD.

Immune Factors

Immune dysregulation is central to the pathogenesis of IBD. Interactions between intestinal mucosal epithelial cells, stromal cells, mast cells, endothelial cells, and immune cells help regulate the dynamic balance of intestinal mucosal immunity and maintain structural stability. Disruption of this balance can result in tissue damage and chronic inflammation, leading to the development of IBD. Immune cells, including neutrophils, macrophages, T lymphocytes, and B lymphocytes, release antibodies, cytokines, and inflammatory mediators that contribute to tissue destruction and inflammatory changes.

Pathology

Ulcerative Colitis (UC)

UC primarily affects the colon and rectum, occasionally involving the terminal ileum and rarely involving the appendix or the upper gastrointestinal tract. Lesions exhibit a diffuse and continuous distribution, predominantly confined to the mucosal layer, with no significant abnormalities in the serosal layer. Microscopically, the inflammation is nonspecific, localized mainly to the mucosa and submucosa. The lamina propria displays infiltration by lymphocytes, plasma cells, and monocytes, with large numbers of neutrophils and eosinophils seen during acute phases. Destruction of glands is an important characteristic, with crypt abscesses frequently observed in the crypt bases, accompanied by epithelial cell necrosis and structural disruption. Goblet cell reduction, Paneth cell metaplasia, epithelial hyperplasia, and increased nuclear mitotic activity are also observed.

Crohn's Disease (CD)

CD can affect any part of the gastrointestinal tract, with the terminal ileum being the most commonly involved site, while rectal involvement is rare. Lesions exhibit a segmental distribution. Microscopically, both acute and chronic inflammatory cells, including monocytes, plasma cells, eosinophils, mast cells, and neutrophils, infiltrate through all layers of the intestinal wall. Fissure-like ulcers and non-caseating granulomas, composed of epithelioid cells and multinucleated giant cells, are characteristic. Submucosal edema, dilated lymphatic and blood vessels, as well as prominent, twisted nerve fibers and proliferating ganglion cells, may also be seen. Fibrous tissue proliferation commonly accompanies these changes.

Clinical Manifestations

Ulcerative colitis (UC) and Crohn's disease (CD) share several clinical characteristics. Both conditions often present with a subacute or chronic onset, though in recent years, acute fulminant onset has also been observed in some cases. Common symptoms include abdominal distension, abdominal pain, and diarrhea. Stool may present as mucus-like loose stools, mucoid purulent stools, purulent bloody stools, or even bloody watery stools, potentially accompanied by tenesmus. Fever of varying degrees may occur, along with extraintestinal manifestations such as arthritis, ankylosing spondylitis, skin rash, and iridocyclitis. Prolonged or recurrent disease can significantly impact nutrition and growth in children. Both conditions may also result in complications like gastrointestinal bleeding, intestinal strictures, intestinal obstruction, or intestinal perforation.

Distinct clinical features differentiate UC and CD. In Crohn's disease, lesions often involve the ileocecal region, with abdominal pain frequently localized to the right lower quadrant. The pain is often colicky or cramping, occurring in episodes, and commonly triggered after meals. Stools may be mucus-like or watery and may also exhibit alternating patterns of constipation and diarrhea. Because of its involvement in the small intestine, the disease more significantly affects nutrient absorption and growth. Early cases may be misdiagnosed as appendicitis, while chronic cases may be misdiagnosed as intestinal tuberculosis. Unlike adults, pediatric Crohn's disease patients, due to a shorter disease duration, rarely develop palpable abdominal masses but may present with perianal lesions such as perianal fistulas, abscesses, and anal fissures.

In ulcerative colitis, intestinal damage typically starts in the distal colon and sigmoid colon. Abdominal pain is thus often localized to the left lower quadrant, characterized by persistent dull or aching pain, which may be relieved after diarrhea. Stools are often mucus-like, purulent, or bloody, progressing to bloody watery stools in severe cases. Tenesmus is common, and the condition may be misdiagnosed as dysentery or infectious colitis.

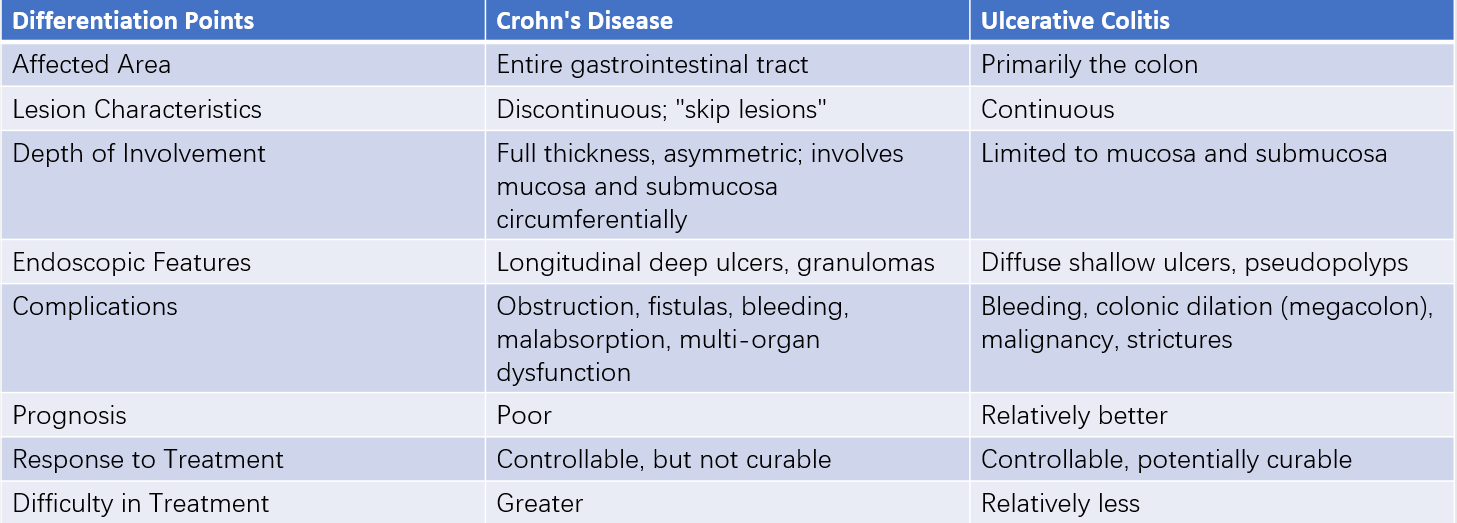

Table 1 Differentiation between Crohn's disease and ulcerative colitis

Auxiliary Examinations

Laboratory Tests

Common laboratory evaluations include complete blood counts, erythrocyte sedimentation rate (ESR), C-reactive protein (CRP), and serum albumin. During active disease, elevated leukocyte count, CRP, and accelerated ESR are frequently observed, while persistent or severe disease may result in decreased serum albumin. Stool routine tests and cultures help differentiate non-IBD intestinal infections. Serological markers include perinuclear anti-neutrophil cytoplasmic antibodies (p-ANCA) and anti-Saccharomyces cerevisiae antibodies (ASCA), which are relatively specific for UC and CD, respectively, and assist in diagnosing and distinguishing the two conditions.

Gastrointestinal Endoscopy

Comprehensive endoscopic evaluation, including esophagogastroduodenoscopy and colonoscopy, is recommended for suspected pediatric IBD cases. Small intestinal endoscopy has unique diagnostic value for Crohn's disease involving the small intestine, while capsule endoscopy can be used in older children to observe small intestinal Crohn's disease. However, capsule endoscopy does not allow for tissue biopsy.

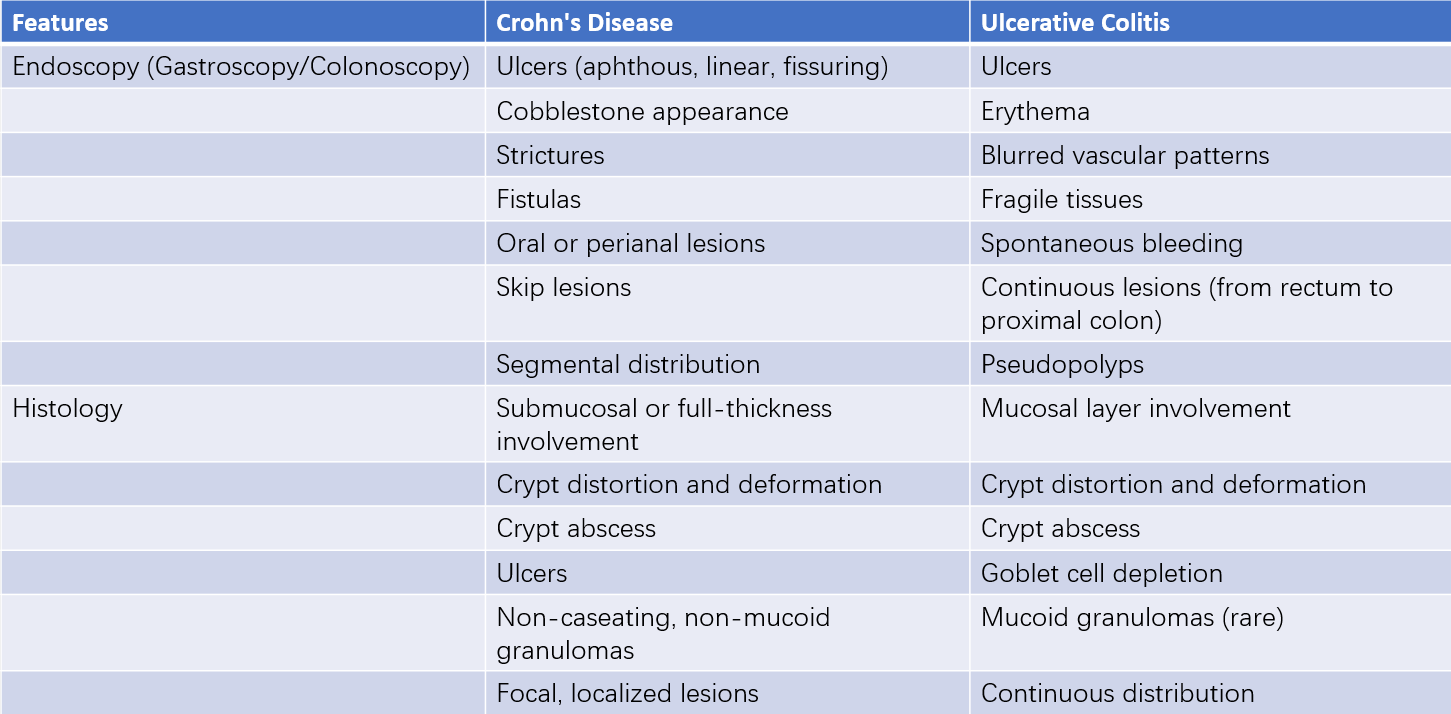

Table 2 Endoscopic and histologic features of inflammatory bowel disease

X-Ray Barium Enema Examination

Gastrointestinal barium studies and double-contrast barium enemas reveal IBD-related lesions, strictures, rigidity, and internal fistulas. Certain radiological findings may suggest active Crohn's disease, such as cobblestone-like mucosal changes, ulcers, bowel loop separation, and skipping segmental distribution of lesions. In cases where colonic narrowing prevents complete colonoscopic examination, barium enema serves as an effective diagnostic tool. However, in cases of severe acute disease, barium enema is contraindicated due to the risk of exacerbation or toxic megacolon.

Abdominal CT Scan

Features detected include segmental bowel wall thickening (wall >3 mm), multilayered bowel wall enhancement, or stratification with prominent mucosal enhancement and submucosal hypoattenuation. Twisted, dilated, or increased mesenteric vasculature, mesenteric lymphadenopathy, and extraintestinal complications such as fistulas, sinus tracts, abscesses, perforations, or strictures may also be observed.

MRI or MRI Enterography

Using gas or isotonic solutions to distend the intestinal tract, combined with intravenous administration of gadolinium contrast, provides clear visualization of the intestinal lumen, bowel wall, and extraintestinal structures. With its excellent contrast resolution, multiplanar imaging capability, and lack of radiation exposure, MRI is increasingly utilized in the diagnosis of pediatric Crohn's disease.

Diagnosis and Differential Diagnosis

IBD should be highly suspected in children with symptoms such as abdominal pain, diarrhea, hematochezia, and weight loss lasting for more than four weeks. A diagnosis is made by combining clinical features with findings from laboratory tests, endoscopic examinations, histopathology, and imaging studies. Due to the unique therapeutic approach required, differentiation from other conditions is essential.

Intestinal Tuberculosis

Ileocecal tuberculosis is particularly challenging to distinguish from Crohn's disease. Endoscopic findings may lack distinguishing features; however, longitudinal ulcers are more common in Crohn's disease, while transverse ulcers are more typical of tuberculosis. Fistulas and perianal lesions are rare in intestinal tuberculosis. For difficult cases, a trial of diagnostic anti-tubercular therapy may be considered.

Acute Appendicitis

Acute appendicitis presents with abrupt onset, a short disease course, and infrequent diarrhea. Migratory right lower quadrant pain and significantly elevated leukocyte counts are key differentiating features.

Other Differential Diagnoses

Chronic bacterial dysentery, amoebic colitis, hemorrhagic necrotizing enteritis, abdominal purpura, Behçet's disease, and intestinal lymphoma should also be considered during differential diagnosis.

Treatment

The treatment goals for pediatric inflammatory bowel disease (IBD) are consistent with those for adult patients. These include achieving and maintaining clinical remission and mucosal healing, preventing complications, enhancing quality of life, and minimizing adverse effects on growth and development.

Nutritional Support

The peak onset of IBD in children often coincides with critical periods of growth and development. In addition to increased nutritional demands during these stages, children with IBD frequently experience decreased appetite, impaired nutrient absorption, and increased nutrient loss. Nutritional therapy is therefore an essential component of treatment. Exclusive enteral nutrition can be used as induction therapy for mild to moderate pediatric Crohn's disease. Research has demonstrated that exclusive enteral nutrition is as effective as corticosteroids in inducing remission in Crohn's disease, while offering superior benefits in improving nutritional status and minimizing medication side effects.

Pharmacological Therapy

Aminosalicylates

5-aminosalicylic acid (5-ASA) is one of the most commonly used drugs for the treatment and prevention of relapse in IBD. It exerts effects through local anti-inflammatory actions, free radical scavenging, and immunosuppressive capabilities. 5-ASA can be used as induction therapy for ulcerative colitis (UC) and may be administered orally and/or rectally. It is the first-line treatment for induction and maintenance therapy in patients with mild to moderate UC. However, there is ongoing debate regarding the use of 5-ASA for induction and remission in pediatric Crohn's disease patients. Current evidence supports its use in children with mild colonic Crohn's disease, with dosing comparable to that used in UC patients.

Corticosteroids

Corticosteroids reduce inflammation by decreasing capillary permeability, stabilizing cell membranes, and inhibiting the release of inflammatory mediators such as leukotrienes, prostaglandins, and thromboxanes. They are effective for managing clinical symptoms and controlling acute active inflammation. Corticosteroids are generally indicated for acute exacerbations of IBD in cases where sufficient treatment with 5-ASA fails. However, they are not typically used for maintenance therapy. In children, oral prednisone is initiated at 1–2 mg/kg/day, with gradual dose reduction as symptoms improve until the medication is fully discontinued. Methylprednisolone may also be administered intravenously at 1–1.5 mg/kg/day. Long-term use of corticosteroids in pediatric IBD patients is not recommended. Some children may develop steroid dependency, experiencing symptom recurrence during dose tapering, particularly those with early-onset disease.

Immunosuppressive Agents

Immunosuppressive agents are commonly used in cases where aminosalicylates and corticosteroid therapy prove ineffective or in steroid-dependent patients. Frequently used agents include thiopurines such as 6-mercaptopurine (6-MP) and azathioprine (AZA), methotrexate, and calcineurin inhibitors (e.g., cyclosporine and tacrolimus). For Crohn's disease, thiopurines reduce postoperative clinical and endoscopic relapse; however, they have a slow onset and are not suitable for acute treatment. Clinical efficacy is generally observed around three months after initiation of therapy, making early consideration of these drugs appropriate for moderate to severe pediatric Crohn's disease.

Thiopurines and methotrexate are suitable for the following indications:

- Maintenance of remission in UC cases that are difficult to sustain with aminosalicylates or when patients are intolerant to these drugs.

- Maintenance of remission in Crohn's disease.

- Steroid dependency.

Recommended doses for thiopurines are 1.5–2.5 mg/kg/day for AZA and 0.75–1.5 mg/kg/day for 6-MP. Common side effects include bone marrow suppression, hepatotoxicity, and pancreatitis. To mitigate these risks, initial dosing is typically started at one-third or half of the full dose and gradually increased to the target dose over approximately four weeks. Regular monitoring of complete blood counts and liver function is required during this period.

Biologic Therapy

Research suggests that elevated levels of tumor necrosis factor-α (TNF-α) play a critical role in the pathogenesis of IBD. Biologic therapies targeting the expression of TNF-α, such as infliximab (IFX), a monoclonal antibody against TNF-α, have been widely applied in clinical practice. Numerous studies have demonstrated its effectiveness, establishing it as one of the most effective medications for inducing and maintaining remission in Crohn’s disease (CD). Indications for IFX include:

- Induction and maintenance therapy for moderate to severe active CD.

- Induction therapy for steroid-refractory active CD.

- Treatment of fistulizing CD.

- CD with severe extraintestinal manifestations, such as arthritis or pyoderma gangrenosum.

- Pediatric patients with high-risk factors, such as deep ulcers on endoscopy, persistent severe activity despite adequate induction therapy, extensive disease, growth failure, severe osteoporosis, inflammatory strictures or perforations at presentation, or severe perianal disease.

- "Rescue" therapy for severe ulcerative colitis (UC).

For pediatric IBD, the initial dose of IFX is 5 mg/kg, administered at weeks 0, 2, and 6 as induction therapy. Treatment is discontinued if remission is not achieved after three doses. For patients who respond, the same dose is administered every eight weeks as long-term maintenance therapy. Ongoing steroid therapy prior to IFX infusion is continued until clinical remission is achieved, after which steroids are gradually tapered and discontinued. For patients who have not previously received immunosuppressive therapy, combination therapy with IFX and azathioprine (AZA) has been shown to improve steroid withdrawal rates and mucosal healing. There is currently insufficient evidence to determine the optimal duration for IFX therapy. For patients who have received IFX maintenance therapy for one year, maintained steroid-free remission, mucosal healing, and normal C-reactive protein (CRP) levels, discontinuation of IFX therapy with continuation of immunosuppressive maintenance therapy may be considered. Relapse following discontinuation of IFX therapy may respond to reintroduction of IFX. However, potential adverse effects of IFX include an increased risk of infections, malignancy, and immune reactions.

Antibiotics

Metronidazole and ciprofloxacin are the most commonly used antibiotics for treating Crohn’s disease. For patients with high fever or laboratory evidence of severe infection (e.g., intra-abdominal or pelvic abscesses), ultrasound or CT imaging is used to confirm abscess formation. Broad-spectrum antibiotics may be necessary for aggressive anti-infective treatment in such cases.

Other Medications

Reports have been published on the use of probiotics and thalidomide in the treatment of IBD. Thalidomide has dual immunosuppressive and immunostimulatory effects. It inhibits the production of TNF-α and IL-12 by monocytes, alters adhesion molecule levels, and consequently reduces leukocyte migration in inflamed tissues, suppressing inflammatory responses. Additionally, thalidomide exhibits antiangiogenic properties and scavenges oxygen free radicals.

Other Therapies

For very early-onset IBD (VEO-IBD), hematopoietic stem cell transplantation has been tried, with successful cases reported both domestically and internationally.

Surgical Treatment

Emergency Surgery

Life-threatening complications such as intestinal perforation, intractable bleeding, or toxic megacolon that fail to respond to medical therapy necessitate prompt surgical intervention.

Elective Surgery

Elective surgery may be considered for patients with refractory symptoms unresponsive to medical therapy, intolerance to long-term medication, or conditions such as intractable fistulas and sinus tracts.

Psychological Support

Pediatric patients with IBD often experience emotional issues such as low mood, depression, and reduced self-esteem, which may impair social functioning. The chronic nature of the disease, side effects of corticosteroid therapy, delayed growth and development, and delayed puberty significantly impact the mental health of children and adolescents. Efforts to reduce psychological burdens in conjunction with treating the primary disease are important, and assistance from mental health professionals may be required when necessary.

The treatment of pediatric IBD requires a collaborative multidisciplinary team. This team typically includes pediatric gastroenterologists, pediatric surgeons, nutritionists, mental health professionals, specialized nursing staff, and adult gastroenterologists (for transitioning to adult care). Optimal outcomes for pediatric IBD patients depend on the collective expertise and efforts of this specialized team.