Poliomyelitis is a highly contagious disease caused by the poliovirus. It is clinically characterized by varying degrees of flaccid paralysis, with severe cases leading to death due to respiratory muscle paralysis.

Etiology

Poliovirus belongs to the genus Enterovirus within the family Picornaviridae. It encodes four capsid proteins and has three serotypes (Types I, II, and III), each capable of causing disease without cross-immune protection. The virus is highly resilient in external environments, being resistant to cold, acid, ether, and chloroform, and can survive for long periods at temperatures below -20°C. Inactivation can be achieved through high temperatures, ultraviolet light exposure, chlorinated disinfectants, or oxidative agents.

Epidemiology

Children and asymptomatic carriers are the main sources of infection, shedding the virus through nasal and pharyngeal secretions and feces. Transmission commonly occurs via the digestive tract, though early-stage infection can spread through respiratory droplets. The virus can persist in the feces for up to two months. Isolation typically lasts for 40 days. Humans are universally susceptible to infection, and immunity against the same serotype is acquired after infection.

Pathogenesis

The virus enters the human body orally, replicating in the lymphoid tissues of the pharynx and ileum while being excreted. Individuals with strong immunity develop protective antibodies and remain asymptomatic, forming an inapparent infection. In a minority of cases, the virus enters the bloodstream, causing viremia and affecting respiratory and digestive tract tissues, leading to prodromal symptoms. If the immune system clears the virus, an abortive infection occurs; otherwise, the virus proliferates extensively in lymphoid tissues, re-entering the bloodstream to initiate secondary viremia. The virus then invades the central nervous system, primarily targeting the motor neurons of the anterior horn in the spinal cord, as well as other parts of the spinal cord and brain. Specific antibodies (IgM, IgG, and IgA) are produced, with IgA secreted in the gut playing a crucial role in antiviral defense.

Pathology

Poliovirus mainly affects the central nervous system, causing permanent damage to the anterior horn motor neurons and gray matter, with the cervical and lumbar segments most severely impacted. Lesions are multiple, scattered, and asymmetric. Histological findings include chromatolysis in neural cells, surrounding tissue congestion, edema, and inflammatory cell infiltration around blood vessels. Early lesions may be reversible, but severe damage results in neuronal death, scarring, and persistent paralysis. Occasionally, other organs may also be affected.

Clinical Manifestations

The incubation period typically lasts 8–12 days. Clinical presentations are classified into asymptomatic infections (accounting for over 90%), abortive infections (approximately 4–8%), non-paralytic cases, and paralytic cases. Paralytic poliomyelitis is the classic form, further divided into distinct phases:

Prodromal Phase

Features include fever, general malaise, loss of appetite, excessive sweating, sore throat, cough, and nasal discharge, as well as nonspecific gastrointestinal symptoms such as nausea, vomiting, abdominal pain, and diarrhea. These symptoms last 1–4 days, resolving without progression in abortive cases.

Pre-Paralytic Phase

Most patients progress from the prodromal phase to the pre-paralytic phase, while a minority experience symptom resolution followed by recurrence of fever and onset of this phase; a small subset begins directly with pre-paralytic symptoms. Common manifestations include high fever, headache, neck and limb pain exacerbated by movement or positional changes, excessive sweating, flushed skin, irritability, meningeal signs, and other central nervous system symptoms. In infants, resistance to being held is common, while in older children, physical examination may reveal the following signs:

- Tripod Sign: Difficulty sitting upright without using both arms for support, forming a triangular posture, indicating spinal rigidity.

- Kiss-the-Knee Test: Inability to bend the neck comfortably to touch the knees with the chin while sitting upright.

- Head Drop Sign: Head falls backward when the trunk is lifted by holding the axillae.

If symptoms resolve after 3–5 days, the case is considered non-paralytic. However, if superficial and deep tendon reflexes weaken and disappear, paralysis may occur.

Paralytic Phase

Paralysis typically develops 2–7 days after illness onset or 1–2 days following recurrent fever, presenting as asymmetric muscle weakness or flaccid paralysis that worsens with fever but does not progress further after fever subsides. Sensory deficits are uncommon, as are disturbances in bladder and bowel function. Paralytic cases are classified based on the affected regions:

- Spinal Type: The most common presentation involves asymmetric flaccid paralysis, predominantly affecting proximal muscle groups in the limbs. Difficulties in head-lifting, sitting, restricted respiratory movements, paradoxical breathing, intestinal paralysis, constipation, urinary retention, or incontinence may occur.

- Bulbar Type: Severe cases involve cranial nerve paralysis alongside respiratory and circulatory dysfunction, often concurrent with spinal type paralysis.

- Cerebral Type: Rare presentation includes diffuse or focal encephalitis, resembling other forms of viral encephalitis.

- Mixed Type: Features of two or more of the above types coexist.

Recovery Phase

Recovery generally begins 1–2 weeks after paralysis onset, with distal muscles showing improvement that gradually progresses proximally. Mild cases recover within 1–3 months, while severe cases require extended recovery periods.

Residual Effects Phase

Permanent paralysis occurs when motor neurons sustain severe damage, with no recovery observed within 1–2 years. Affected muscle groups atrophy, leading to limb or spinal deformities.

Complications

Respiratory muscle paralysis can lead to secondary complications such as aspiration pneumonia and atelectasis. Urinary retention increases the likelihood of urinary tract infections. Prolonged bed rest may result in pressure sores, muscle atrophy, bone demineralization, urinary stones, and renal failure.

Laboratory Examinations

Blood Tests

Peripheral white blood cell counts are generally normal. During the acute phase, erythrocyte sedimentation rates may increase.

Cerebrospinal Fluid (CSF)

In the pre-paralytic and early paralytic phases, an increased cell count (predominantly lymphocytes) may be observed, while protein levels remain mildly elevated, manifesting as a dissociation between cell count and protein levels. By the third week of paralysis, the cell count usually returns to normal, while protein levels continue to rise, normalizing in 4–6 weeks.

Serological Testing

In the early stages of the disease, specific IgM antibodies against poliovirus in serum and CSF can aid in early diagnosis. During the recovery phase, a greater than fourfold increase in specific IgG antibody titers compared to the acute phase holds diagnostic significance.

Virus Isolation

Virus isolation is the most definitive confirmatory test. Within the first week of onset, the virus can be readily isolated from the throat and stool. In the early phase, it may also be isolated from blood and CSF.

Nucleic Acid Detection

RT-PCR can rapidly diagnose the presence of poliovirus nucleic acids in throat swabs, fecal samples, and other specimens. Viral genotyping allows for differentiation between wild-type strains and vaccine-derived strains.

Imaging Studies

On MRI, spinal poliomyelitis may show long T2 hyperintense signals in the anterior horn region of the spinal cord on sagittal views, without space-occupying effects or significant swelling. Axial views reveal T2 hyperintense signals in the anterior horn. Post-contrast studies may show enhancement, although enhancement may be absent. Brainstem involvement often shows symmetrical long T1 and T2 signals in the substantia nigra and striatonigral pathway at the midbrain level.

Diagnosis and Differential Diagnosis

Diagnosis is straightforward in cases with characteristic paralysis. In early stages, diagnosis is often more challenging. Serological testing and viral isolation from stool can confirm the diagnosis. Differential diagnosis is necessary to distinguish poliovirus from other causes of acute flaccid paralysis (AFP).

Acute Infectious Polyneuropathy (Guillain-Barré Syndrome)

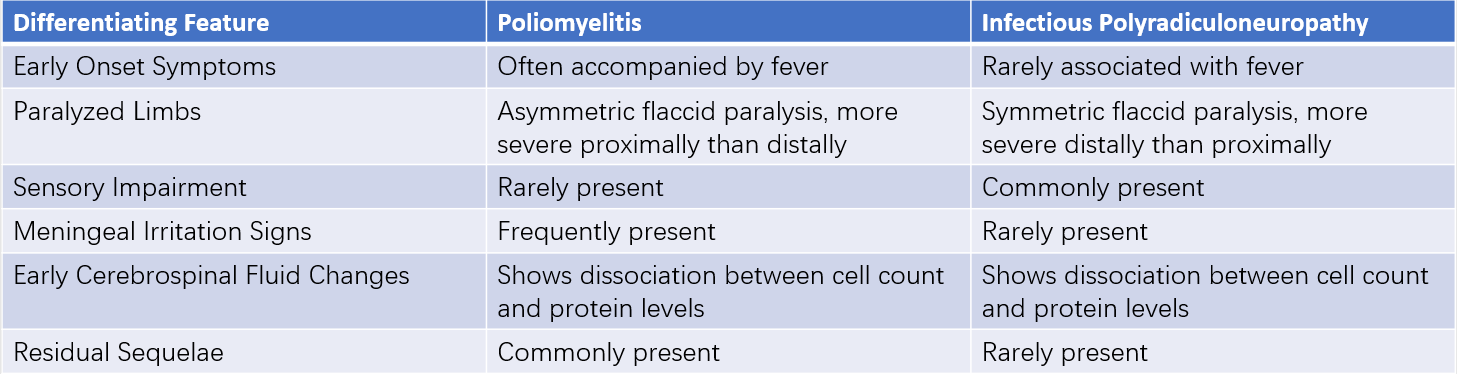

Differential points are detailed in Table 1.

Table 1 Key differentiating features between poliomyelitis (paralytic type) and infectious polyradiculoneuropathy

Other Causes of Flaccid Paralysis

Differential diagnosis includes conditions such as familial periodic paralysis, peripheral neuritis, or pseudoparalysis.

Treatment

Currently, no medication is available to arrest the onset or progression of paralysis. Management typically includes symptomatic and supportive care.

Prodromal and Pre-Paralytic Phases

Patients should remain on bed rest with isolation for 40 days. Overexertion, intramuscular injections, and surgical interventions should be avoided to minimize stimulation. Muscle spasms and pain can be alleviated using heat packs or oral analgesics. Intravenous administration of hypertonic glucose and vitamin C may reduce neural tissue edema. Intravenous immunoglobulin (IVIG) at 400 mg/(kg·day) for 2–3 days may ameliorate the severity of the condition.

Paralytic Phase

Paralyzed limbs should be maintained in functional positions to prevent deformity. Pharmacological interventions include dibazol at 0.1–0.2 mg/(kg·day) as a single daily dose for 10-day courses, which may stimulate the spinal cord and dilate blood vessels. Galantamine may enhance neural conductivity and is administered intramuscularly at doses of 0.05–0.1 mg/(kg·day) for 20–40 days. Vitamin B12 at 0.1 mg/day intramuscularly is used to promote neuronal metabolism. Early use of mechanical ventilation is required for respiratory muscle paralysis. Nasogastric feeding is advised for patients with swallowing difficulties to ensure adequate nutrition. Secondary bacterial infections are treated with appropriate antibiotics.

Recovery and Residual Effects Phases

Rehabilitation therapy, including physical training, should begin as early as possible to prevent muscle atrophy. Therapies such as acupuncture, massage, and physiotherapy may promote recovery of function. Severe limb deformities may require surgical correction.

Prevention

Active Immunization

All children, except those infected with HIV, should receive active immunization against poliovirus. The inactivated poliovirus vaccine (IPV) is used for routine immunization. A primary immunization schedule starts at 2 months of age with one IPV dose, followed by additional doses of an attenuated oral poliovirus vaccine at 3 months, 4 months, and 4 years of age. Booster immunizations can be administered to children under five as needed.

Passive Immunization

Unvaccinated children under five years of age who have close contact with infected individuals, as well as children with congenital immune deficiencies, may receive intramuscular immunoglobulin at a dose of 0.3–0.5 ml/(kg·dose) daily for two consecutive days. This can help prevent disease onset or mitigate symptoms. Active immunization should follow thereafter.