Measles is a highly contagious disease caused by the measles virus. Clinically, it is characterized by fever, upper respiratory tract inflammation, conjunctivitis, Koplik spots in the oral mucosa, generalized maculopapular rash, and pigmentation with branny desquamation following rash resolution.

Pathogen

The measles virus is an RNA virus belonging to the Paramyxoviridae family. It has a spherical structure and six structural proteins, including envelope proteins (M, F, and H) and nucleocapsid proteins (N, P, and L). The H protein binds to cellular receptors, the F protein is involved in viral fusion with cells, and the M protein facilitates viral release. The measles virus exhibits weak survivability outside the body, is heat-sensitive, and is vulnerable to ultraviolet light and disinfectants.

Epidemiology

Children infected with measles are the sole source of transmission. The virus is shed from the eyes' conjunctiva, nasopharyngeal secretions, blood, and urine. The disease remains contagious for five days before and after the appearance of the rash. If complications occur, the infectious period may extend to 10 days post-rash. Immunity acquired after infection is generally lifelong.

Pathogenesis

Following entry through the nasopharynx, the measles virus replicates in respiratory epithelial cells and local lymphoid tissues, subsequently entering the bloodstream. The virus spreads to other organs via monocytes, causing widespread damage and triggering a series of clinical symptoms. Specific IgM antibodies appear within 2–3 days post-infection, while specific IgG antibodies emerge simultaneously or slightly later. Cell-mediated immunity plays a primary role in antiviral defense. Due to immune system impairment, patients may experience complications such as laryngitis, bronchopneumonia, encephalitis, or reactivation of latent tuberculosis. Severe cases in immunocompromised children may result in serious complications like severe pneumonia or encephalitis, leading to death.

Pathology

Warthin-Finkeldey giant cells with viral inclusions both inside and outside the nucleus are characteristic pathological findings for measles. Vasodilation, endothelial cell edema and proliferation, mononuclear cell infiltration, and serous exudation in dermal and submucosal capillaries lead to the formation of Koplik spots and the rash. Red blood cell lysis at rash sites results in brown pigmentation following rash resolution. Subacute sclerosing panencephalitis (SSPE) is characterized by degeneration of cortical and white matter regions of the brain, with inclusions present in cellular nuclei and cytoplasm.

Clinical Manifestations

Classic Measles

Incubation Period

The incubation period ranges from 6 to 18 days, with an average of 10 days. Mild fever and general discomfort may occur toward the end of this period.

Prodromal Period

This period typically lasts 3–4 days and presents with the following features:

- Fever: Often moderate or higher, with variable patterns.

- Symptoms such as cough, sneezing, pharyngeal congestion, and particularly coryza, conjunctival injection, eyelid edema, photophobia, and lacrimation are characteristic of measles.

- Koplik Spots: A hallmark early sign of measles, appearing 1–2 days before the rash. Initially found on the buccal mucosa across from the upper and lower molars, these gray-white granule-sized lesions are surrounded by red halos, rapidly increasing in number within 1–2 days. They may spread to the mucosa of the lips and disappear after the rash, leaving behind dark red spots.

- Nonspecific symptoms may include fatigue, loss of appetite, lethargy, and gastrointestinal manifestations such as vomiting and diarrhea, particularly in infants. Occasionally, transient urticaria, faint erythema, or scarlet fever-like rashes may precede the appearance of typical measles rash, which causes prior skin changes to subside.

Exanthematous Period

Rash typically emerges 3–4 days after fever onset, accompanied by worsening systemic symptoms. Fever may abruptly spike to 40°C, and cough becomes severe, with lethargy or irritability. Severe cases may involve delirium or convulsions. Rash initially appears behind the ears and along the hairline, gradually spreading to the forehead, face, neck, trunk, limbs, and eventually the palms and soles. The rash starts as red maculopapules with erythematous congestion, sparing intervening skin, and lacks itching. Over time, some lesions coalesce into patches and darken to deep red. Lung sounds may reveal dry or wet rales.

Recovery Period

Without complications, fever diminishes 3–4 days after rash onset, and systemic symptoms, appetite, and overall condition gradually improve. The rash resolves in the same order it appeared, leaving behind brown pigmentation and branny desquamation that typically clears within 7–10 days.

Atypical Measles

Mild Measles

This is characterized by transient low-grade fever, mild coryza symptoms, minimal systemic signs, sparse and faint rash, and rapid resolution without pigmentation or desquamation post-rash. Diagnosis usually requires epidemiological data and serologic testing for measles virus.

Severe Measles

This is marked by persistent high fever, severe toxemia, convulsions, and coma. The rash often appears dense and confluent, with purplish-blue hemorrhagic lesions. Mucosal and gastrointestinal bleeding, hemoptysis, hematuria, and thrombocytopenia may arise, known as "black measles." Some cases involve poor rash appearance, abrupt rash disappearance, cold extremities, low blood pressure, and circulatory failure. Pneumonia, heart failure, and other complications are common, with high mortality rates.

Allergic Measles

This primarily occurs in individuals who were vaccinated with the inactivated measles vaccine and later reinfected with wild-type measles virus strains. Typical symptoms include persistent high fever, fatigue, myalgia, headache, and limb swelling. Rash presentation varies, with irregular rash progression and likelihood of pneumonia development. This type is rare, and clinical diagnosis can be challenging; serologic or virologic testing aids diagnosis.

Complications

Respiratory System

Common complications involve laryngitis and pneumonia. Pneumonia is the most frequent and severe complication of measles, often presenting with significant clinical symptoms and poor prognosis. It accounts for over 90% of measles-related deaths in children. Interstitial pneumonia caused directly by the measles virus is typically mild. Secondary bacterial pneumonias are most often due to Staphylococcus aureus, Streptococcus pneumoniae, or Haemophilus influenzae, and may lead to empyema or pyopneumothorax. Some cases involve viral or mixed infections with multiple pathogens.

Myocarditis

Mild cases present with muffled heart sounds, tachycardia, and transient electrocardiogram abnormalities, while severe cases may lead to heart failure or cardiogenic shock.

Nervous System

Measles Encephalitis

This frequently begins 2–6 days after the rash with recurrent fever. Clinical features and cerebrospinal fluid findings resemble those of viral encephalitis and are not directly related to the severity of the measles infection. The condition has a high fatality rate, and survivors may experience lasting effects such as intellectual disability, paralysis, or epilepsy.

Subacute Sclerosing Panencephalitis (SSPE)

This is a rare late complication of measles, with onset typically occurring 2–17 years after primary infection. Initial symptoms are subtle, often involving behavioral or emotional changes. Progressive symptoms include intellectual decline, ataxia, sensory deficits, myoclonus, and eventually coma, spastic paralysis, and death. Persistent strong positivity for measles virus IgG antibodies in the serum or cerebrospinal fluid is a hallmark of the disease.

Tuberculosis Reactivation

Temporary suppression of immune responses in measles patients can cause latent tuberculosis foci to reactivate, potentially leading to disseminated miliary tuberculosis or tuberculous meningitis.

Laboratory Investigations

Complete Blood Count

Peripheral blood shows a decrease in total white blood cell and neutrophil counts, with a relative increase in lymphocytes.

Multinucleated Giant Cell Examination

From two days before the rash to one day after, multinucleated giant cells or inclusion bodies may be observable in smears of nasal, pharyngeal secretions, or urinary sediment stained with Romanowsky dye, yielding a high rate of positivity.

Serological Testing

Specific IgM antibodies against measles virus can be detected using enzyme-linked immunosorbent assay (ELISA), which offers high sensitivity and specificity. Positivity is detectable in the early stage of the rash.

Antigen and Nucleic Acid Detection

Immunofluorescence can detect viral antigens in nasopharyngeal secretions or urinary sediment cells, while RT-PCR (reverse transcriptase polymerase chain reaction) can identify measles virus RNA, enabling early rapid diagnosis.

Viral Isolation

Blood, urine, or nasopharyngeal secretions obtained during the prodromal or early rash phase can be used to isolate the measles virus.

Diagnosis and Differential Diagnosis

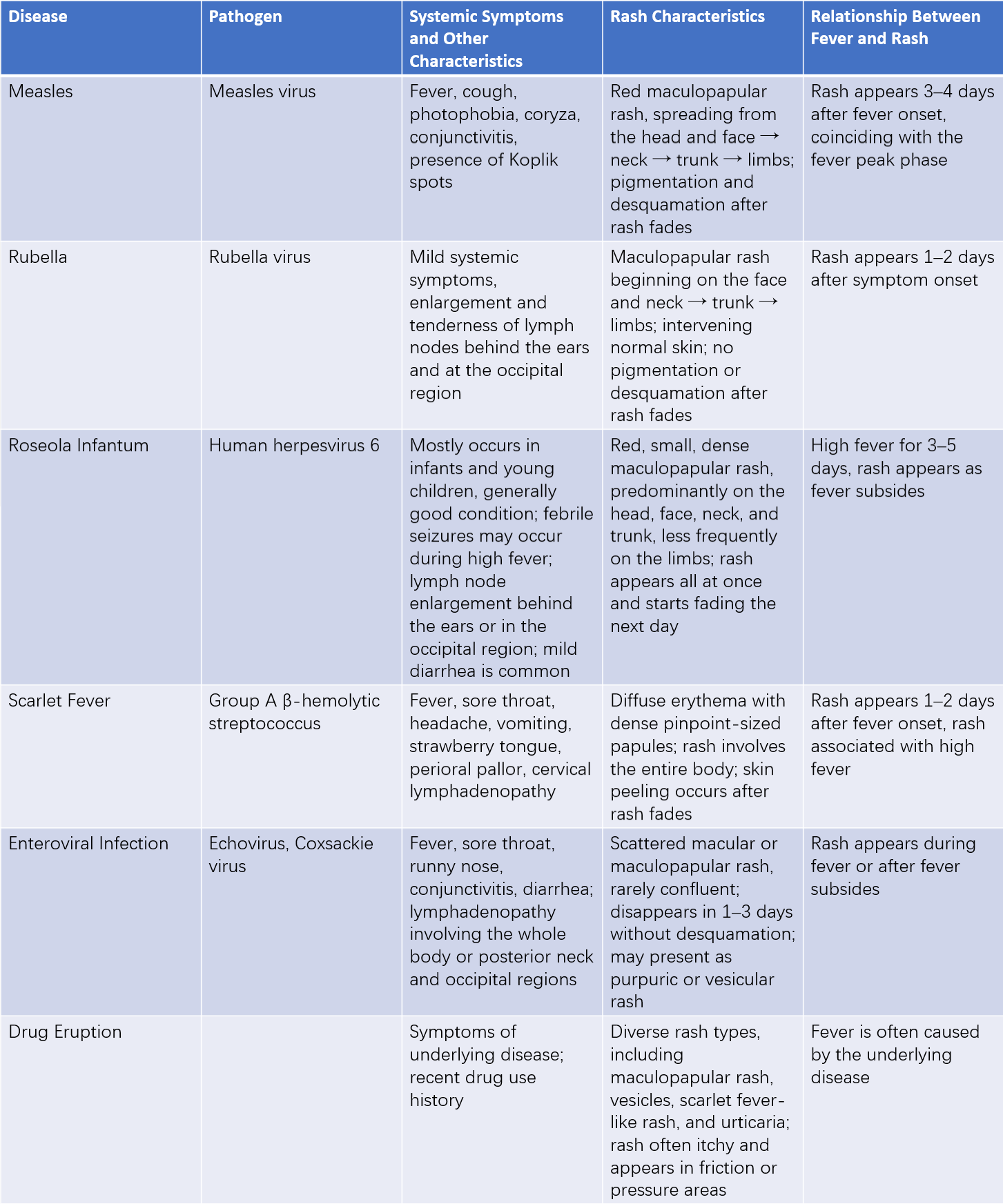

Measles should be suspected based on epidemiological history, contact with confirmed cases, acute fever, photosensitivity, and coryza symptoms. Before rash onset, the presence of Koplik spots confirms the diagnosis. Desquamation and pigmentation following rash resolution aid retrospective diagnosis. Confirmation can be achieved through measles-specific IgM antibody positivity, detection of measles virus RNA by RT-PCR, or virus isolation. Differential diagnoses include rubella, roseola infantum, scarlet fever, and enteroviral infections.

Table 1 Differential diagnosis of common exanthematous diseases in children

Treatment

There is no specific cure. Management involves symptomatic treatment, enhanced care, and prevention of complications. Most patients without complications recover within 2–3 weeks of disease onset.

General Care

Rest is recommended, along with maintaining an appropriate indoor temperature, humidity, and fresh air. Patients should avoid exposure to strong light while maintaining cleanliness of the skin, eyes, nose, and mouth. Hydration and a diet rich in easily digestible, nutritious foods are suggested.

Symptomatic Treatment

Antipyretics may be used cautiously for high fever, avoiding sudden cooling, particularly during the rash phase. Sedatives may be given for irritability, and antitussives or nebulized treatments can be used for frequent, severe cough.

Treatment of Complications

Appropriate treatments are administered for complications. Antibiotics may be given to address secondary bacterial infections.

Prevention

Enhancing population immunity and reducing the number of susceptible individuals is crucial for measles elimination.

Active Immunization

Prophylactic vaccination with the live attenuated measles vaccine is performed. The initial measles vaccination is administered at eight months of age, with a second dose given at 18–24 months as part of the immunization schedule. Based on epidemiological needs, intensified immunization campaigns may be conducted among high-risk populations over short periods.

Passive Immunization

Administration of intramuscular immune globulin (0.25 mL/kg, maximum 15 mL) within five days of exposure can prevent or mitigate illness. Passive immunity lasts 3–8 weeks, requiring subsequent active immunization.

Control of Sources of Infection

Early detection, reporting, isolation, and treatment of measles cases are essential. Isolation generally lasts until five days after the rash appearance; in cases of pneumonia, it should extend to ten days. Susceptible individuals exposed to measles should undergo quarantine for three weeks and receive passive immunization. For suspected measles cases, epidemiological investigation, laboratory testing, and timely reporting are key, with targeted isolation measures to prevent outbreak spread.

Interrupting Transmission

Susceptible children should avoid crowded areas during outbreaks. Rooms exposed to the virus should be ventilated and disinfected with ultraviolet light, and patient clothing should be aired out in sunlight. Mild cases without complications can be managed at home under isolation.