Kawasaki disease (KD) was first described in 1967 by Japanese physician Tomisaku Kawasaki and is also known as mucocutaneous lymph node syndrome (MCLS). Approximately 20% of untreated pediatric patients develop coronary artery abnormalities. Since 1970, cases have been reported worldwide, with a higher incidence among Asian populations. The disease occurs sporadically or in small epidemics and can manifest during any season. It primarily affects infants and young children, with over 85% of cases occurring in children under 5 years of age. The male-to-female ratio is approximately 1.5–2.0:1.

Etiology and Pathogenesis

Etiology

The exact cause remains unknown. Epidemiological studies suggest potential involvement of environmental factors and various pathogens, such as Rickettsia, Staphylococcus, Streptococcus, retroviruses, and Mycoplasma. However, definitive evidence for these associations is lacking. Genetic susceptibility may also play a role.

Pathogenesis

The mechanism of Kawasaki disease remains unclear. It is generally considered that causative agents trigger abnormal immune responses, leading to acute systemic vasculitis involving medium and small blood vessels. During the acute phase, immune dysregulation predominates, with abnormal activation of T cells and stimulation of B cells, resulting in excessive production of inflammatory cytokines (e.g., interleukins and tumor necrosis factor-alpha) and anti-endothelial cell autoantibodies, which contribute to vascular inflammation and injury. Studies indicate that certain pathogens, such as Staphylococcus aureus and group A Streptococcus, may act as superantigens, eliciting strong T and B cell-mediated immune responses that damage the vascular walls. Inflammatory infiltrates in affected vascular tissues often include IgA-producing plasma cells, monocytes/macrophages, and CD8+ T cells. Genetic susceptibility related to immune dysfunction may also play a role in the development and progression of Kawasaki disease.

Pathology

The pathological changes in Kawasaki disease involve systemic vasculitis, particularly affecting the coronary arteries. The pathological features include three interrelated types of vascular lesions:

- Acute, self-limited necrotizing arteritis: Occurs during the first two weeks of the disease course. It is characterized primarily by neutrophilic inflammation that sequentially damages the endothelium, intima, internal elastic lamina, media, external elastic lamina, and adventitia, leading to the formation of saccular aneurysms.

- Subacute/chronic arteritis: Develops within the first two weeks of the disease, persisting for months or years. It is dominated by small lymphocytic inflammation that originates in the adventitia or perivascular tissues and progresses to damage the arterial walls and lumen. Mild inflammation causes minimal vascular damage, whereas severe inflammation can lead to progressive dilation and aneurysm formation.

- Fibroproliferation in the arterial lumen: Co-occurs with subacute/chronic arteritis, persisting for months or years. It involves pathological proliferation of smooth muscle-derived myofibroblasts in the intima, forming circumferential and symmetrical structures that cause varying degrees of luminal narrowing.

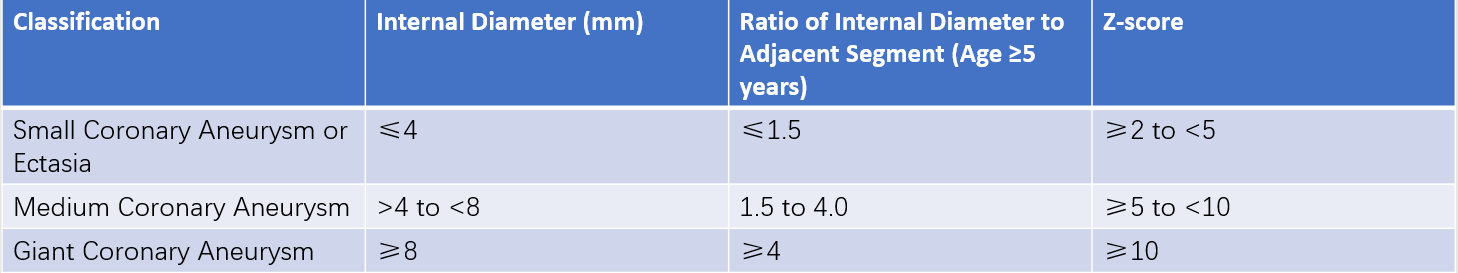

Coronary artery abnormalities primarily manifest as varying degrees of aneurysm formation.

Table 1 Classification of coronary artery aneurysms in Kawasaki disease

Stages of Pathological Progression

The pathological evolution of Kawasaki disease can typically be divided into four stages:

- Acute Phase (Days 1–11): Microvasculitis and small-vessel vasculitis are observed, along with periarteritis, endarteritis of medium and large arteries, and inflammation of the endocardium, myocardial stroma, and pericardium.

- Subacute Phase (Days 11–21): There is full-thickness vasculitis of medium arteries, particularly the coronary arteries. Elastic fibers and smooth muscle layers in the arterial walls may rupture, leading to aneurysm and thrombus formation. Microvasculitis and myocarditis become less prominent.

- Recovery Phase (Days 21–60): Vascular inflammation subsides, with gradual recovery of coronary artery lesions. However, intimal thickening, fibrosis, thrombus formation, and granulation tissue may develop, resulting in coronary artery stenosis and occlusion.

- Chronic Phase (After Day 60): This stage may persist for years. Some coronary artery lesions gradually heal, while others progress. Thickening and scarring of the intima in medium arteries can occur. In late stages, ischemic heart disease may emerge.

Clinical Manifestations

Primary Symptoms

Fever

Body temperature ranges from 39–40°C and persists for 7–14 days or longer. The fever often manifests as continuous or intermittent high fever and is unresponsive to antibiotic therapy.

Changes in the Extremities

In the acute phase, erythema and firm edema of the palms and soles may be observed, occasionally accompanied by pain. Desquamation (membranous peeling) of the fingers and toes begins around the nail beds at 2–3 weeks and may extend to the palms and soles. Deep transverse grooves (Beau’s lines) on nails or nail shedding may appear 1–2 months after disease onset.

Skin Rash or BCG-site Redness and Swelling

Rashes typically appear within the first 5 days of fever and are widely distributed, primarily involving the trunk and extremities. These rashes take the form of maculopapular, scarlatiniform, or erythema multiforme-like lesions, although urticarial rash and pustules are rare. Perineal erythema, rashes, and peeling are common. Redness and swelling of previous Bacille Calmette-Guérin (BCG) vaccination sites are relatively specific early signs of Kawasaki disease.

Conjunctival Injection

Bilateral non-exudative conjunctival injection occurs shortly after the onset of fever and usually spares the limbal region and iris. During the first week of fever, slit-lamp examination may reveal anterior uveitis. Subconjunctival hemorrhage and punctate keratitis are occasionally observed.

Oral and Lip Changes

Symptoms include red, dry, cracked, peeling, and bleeding lips; diffuse erythema of the oropharyngeal mucosa; and enlarged, erythematous lingual papillae presenting as a "strawberry tongue."

Cervical Lymphadenopathy

This is generally unilateral, with lymph nodes ≥1.5 cm in diameter. The surface is not red, there is no suppuration, and tenderness may be present. Lymphadenopathy is largely confined to the anterior cervical triangle.

Cardiac Manifestations

Pericarditis, myocarditis, endocarditis, and arrhythmias may develop between weeks 1 and 6 of the disease. Coronary artery lesions typically occur between weeks 2 and 4 but may also emerge during the recovery phase. Boys under 2 years of age with markedly elevated erythrocyte sedimentation rate (ESR), platelet count, and C-reactive protein (CRP) are at higher risk of coronary artery lesions. Rare complications include myocardial infarction, coronary artery aneurysm rupture, severe arrhythmias, or sudden death.

Other Systemic Manifestations

The disease may affect various organs, occasionally as the initial presentation. These manifestations include interstitial pneumonia, aseptic meningitis, gastrointestinal symptoms (e.g., abdominal pain, vomiting, diarrhea, paralytic ileus, hepatomegaly, jaundice), joint pain or arthritis, and sterile pyuria.

Auxiliary Investigations

Laboratory Tests

Complete Blood Count (CBC)

White blood cell (WBC) count is elevated, predominantly neutrophils.

Hemoglobin levels are reduced.

Platelet counts often increase during the second week of the disease, peak in the third week, and return to normal by 4–6 weeks.

Urinalysis and Urine Culture

Findings include presence of leukocytes in the urine without bacterial growth on culture.

Acute-phase Reactants

Findings include elevated CRP, serum amyloid A protein, and ESR.

Blood Biochemistry

Findings include raised levels of transaminases, total bilirubin, creatine kinase, and myocardial enzymes.

Reduced albumin and serum sodium levels can be seen.

Immunological and Inflammatory Markers

Findings include:

- Elevated levels of IL-6, IL-1, tumor necrosis factor-alpha (TNF-α).

- Increased serum IgG, IgM, IgA, IgE, and circulating immune complexes.

- Normal or elevated.complement levels (C3 and total complement) are

Others

Findings include:

- Elevated plasma brain natriuretic peptide (BNP) or N-terminal pro-BNP levels.

- Increased levels of procalcitonin (PCT), serum ferritin, and D-dimer may also be noted.

Electrocardiography (ECG)

Early changes include nonspecific ST-T wave abnormalities. Pericarditis may present with widespread ST-segment elevation and low voltage, while myocardial infarction shows significant ST-segment elevation, T-wave inversions, and abnormal Q waves. Arrhythmias may also occur.

Chest X-ray

Findings may include increased and blurred pulmonary markings or patchy shadows. Cardiomegaly may also be observed.

Ultrasonography

Findings may include hepatomegaly, gallbladder wall edema, gallbladder enlargement, abdominal lymphadenopathy, ascites, and cervical lymphadenopathy. Arterial aneurysm formation may be detected in the neck, axillae, or inguinal areas.

Echocardiography

During the acute phase, pericardial effusion, left ventricular dilatation, and valvular regurgitation (mitral, aortic, or tricuspid) may occur. Coronary artery abnormalities such as coronary artery dilatation or aneurysms may be observed, including size, location, and number of lesions. Intracoronary thrombus may sometimes be seen within giant aneurysms.

Coronary Angiography

This provides a comprehensive assessment of coronary artery lesions. Indicated in cases with multiple coronary aneurysms detected on ultrasound, suspected coronary artery stenosis, or signs of myocardial ischemia on ECG.

Multislice Spiral CT Angiography (CTA)

CTA shows superior ability over echocardiography in detecting coronary artery stenosis, thrombus formation, and vascular calcification. It can partially replace conventional coronary angiography.

Magnetic Resonance Imaging (MRI)

MRI evaluates myocardial inflammation and ischemia caused by coronary artery lesions. Whole-body vascular magnetic resonance angiography can detect arterial aneurysms in other regions and may assist in differentiating from diseases such as Takayasu arteritis or polyarteritis nodosa.

Diagnosis and Differential Diagnosis

Diagnosis

Kawasaki disease is a clinical syndrome that requires exclusion of other diseases. Diagnosis relies mainly on clinical manifestations combined with laboratory findings and is classified into complete Kawasaki disease and incomplete Kawasaki disease.

Complete Kawasaki Disease

Diagnosis requires the presence of fever along with at least four of the following major clinical features:

- Bilateral conjunctival injection.

- Changes in the lips and oral mucosa, including dry, red lips; strawberry tongue; and diffuse erythema of the oropharyngeal mucosa.

- Rash (including isolated redness and swelling of a BCG scar).

- Changes in the extremities, such as erythema and edema of the hands and feet during the acute phase, and periungual desquamation during the recovery phase.

- Non-suppurative cervical lymphadenopathy, usually unilateral, with a diameter of ≥1.5 cm.

Incomplete Kawasaki Disease

Diagnosis is considered when fever lasts ≥5 days and fewer than four major clinical features are present. Laboratory investigations, such as elevated ESR and CRP, along with echocardiographic findings, are used to support the diagnosis. In some cases, diagnosis may require observation of the disease course.

Differential Diagnosis

The disease must be differentiated from other fever-associated rash diseases such as exudative erythema multiforme, systemic juvenile idiopathic arthritis, drug hypersensitivity, sepsis, Epstein-Barr virus infection, and scarlet fever.

Treatment

The primary goals of treatment during the acute phase are to reduce and halt systemic inflammatory reactions, prevent the development and progression of coronary artery lesions, and avoid coronary thrombosis. Treatment should begin promptly after diagnosis is confirmed.

Aspirin

This is administered at a dose of 30–50 mg/kg/day in three divided doses. Fever typically subsides within 48–72 hours, at which point inflammatory markers (e.g., WBC count and CRP) normalize, and the aspirin dose is reduced to 3–5 mg/kg/day for its antiplatelet effect. In cases without coronary artery lesions or with mild coronary artery dilation that resolves within 30 days, aspirin is continued for 2–3 months. For patients with coronary sequelae, treatment and follow-up management depend on the risk stratification of coronary artery lesions. For patients unsuitable for aspirin, dipyridamole or clopidogrel may be used as alternatives.

Intravenous Immunoglobulin (IVIG)

This is administered at 1–2 g/kg (recommended dose is 2 g/kg) as a slow infusion over 8–12 hours. Early administration (within 10 days of symptom onset) effectively reduces fever and prevents coronary artery lesions. IVIG resistance is defined as persistent fever (above 38°C) 36 hours after IVIG completion or recurrent fever (typically 2–7 days after treatment) accompanied by at least one major clinical manifestation of Kawasaki disease, after excluding other causes of fever. Management of IVIG resistance, known as rescue therapy, includes repeating IVIG or using alternative treatments such as corticosteroids or infliximab. Due to potential interference of IVIG with immune responses to live virus vaccines, patients who receive 2 g/kg IVIG should avoid receiving measles, mumps, rubella, or varicella vaccines within 9 months.

Corticosteroids

Due to risks associated with corticosteroids, including thrombosis promotion, increased coronary artery lesion or aneurysm risk, and impaired repair of coronary artery damage, standalone use is not advised. Corticosteroids may be considered in cases of IVIG failure or patients at risk for IVIG resistance.

Other Treatments

Antiplatelet Therapy

For patients without coronary lesions, low-dose antiplatelet therapy is typically continued for 3 months.

For patients with coronary lesions, low-dose antiplatelet therapy is ongoing.

Severe coronary lesions may require a combination of aspirin with dipyridamole or clopidogrel.

Anticoagulation Therapy

This is indicated for patients with giant coronary aneurysms, a history of myocardial infarction, or acute thrombosis.

Options include low molecular weight heparin and warfarin, either for anticoagulation or thrombolysis.

Surgical Treatment

Severe coronary artery disease may necessitate coronary artery bypass grafting or catheter-based interventional procedures.

Other Supportive Therapies

Symptomatic and supportive care is provided based on the patient's condition. This includes fluid supplementation, liver and cardiac function protection, managing heart failure, and correcting arrhythmias.

Prognosis

Kawasaki disease generally has a favorable prognosis, with a recurrence rate of approximately 1%–3%. Children without coronary lesions undergo comprehensive evaluations (including physical examination, ECG, and echocardiography) at 1, 3, 6, and 12 months after discharge and then every 5 years. While small- and medium-sized coronary aneurysms may regress within two years, functional abnormalities such as vascular wall thickening and reduced elasticity often persist. Giant coronary aneurysms may lead to thrombosis and stenosis. Long-term follow-up management is essential for this group, including periodic evaluation of myocardial ischemia and cardiac function, along with guidance on physical activity and nutrition.