Juvenile idiopathic arthritis (JIA) is a common rheumatic disease in children characterized primarily by chronic synovial inflammation of the joints. It may be associated with systemic multi-organ dysfunction and is one of the leading causes of disability or blindness in children. The condition has been referred to by various names, including juvenile rheumatoid arthritis (JRA), Still's disease, juvenile chronic arthritis (JCA), and juvenile arthritis (JA), among others. In 2001, the International League of Associations for Rheumatology (ILAR) defined JIA as "joint swelling or pain of unknown cause persisting for more than six weeks in children under the age of 16."

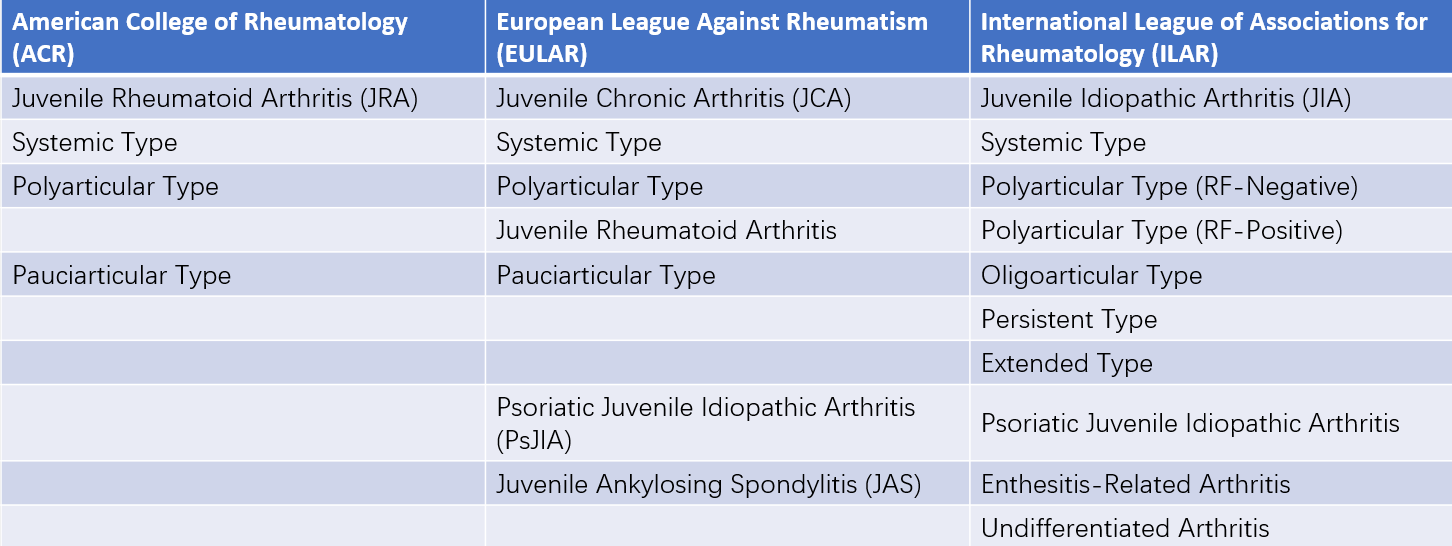

Table 1 Comparison of juvenile idiopathic arthritis (JIA) classifications between the United States, Europe, and international standards

Etiology and Pathogenesis

The exact cause of JIA remains unclear, although multiple factors appear to be involved.

Infectious Factors

Several bacteria (e.g., streptococci, Yersinia, Shigella, Campylobacter, and Salmonella), viruses (e.g., human parvovirus B19, rubella virus, and Epstein-Barr virus), and other pathogens such as Mycoplasma and Chlamydia have been reported to be associated with the disease. However, no definitive evidence currently supports infection as a direct cause of JIA.

Genetic Factors

A genetic predisposition has been strongly supported by studies, particularly in relation to human leukocyte antigen (HLA) markers. Individuals with HLA-DR4 (especially DR10401), DR8 (notably DRB10801), and DR5 (such as DR1*1104) alleles are considered more susceptible to JIA. Additional HLA loci, including HLA-DR6 and HLA-A2, have also been linked to the disease. Other non-HLA genetic variants have been found to be associated with its onset as well.

Immunologic Factors

Multiple studies have demonstrated that JIA is an autoimmune disease:

- Some patients exhibit rheumatoid factor (RF) and antinuclear antibodies (ANA) in their serum and synovial fluid.

- Increased levels of IgG and phagocytic cells have been detected in synovial fluid.

- Elevated concentrations of serum immunoglobulins, including IgG, IgM, and IgA, are common among affected children.

- Peripheral blood CD4+ T cells undergo clonal expansion.

- Serum levels of inflammatory cytokines are markedly elevated.

Based on this evidence, the pathogenesis of JIA may involve infectious microorganisms acting as exogenous antigens and triggering immune responses in genetically predisposed individuals. This activation of immune cells ultimately results in tissue damage through mechanisms such as cytokine release or production of autoantibodies, thereby causing aberrant immune reactions and subsequent damage to self-tissues.

Specific components of certain bacteria and viruses, such as heat shock proteins (HSPs), can act as superantigens by directly binding to T cell receptors (TCR) with a specific variable β-chain (Vβ) structure, leading to the activation of T cells and immune damage. Denatured components of self-tissue, such as altered IgG or collagen, can act as endogenous antigens, eliciting immune responses targeted at self-tissue components and exacerbating immune damage.

Classification and Clinical Manifestations of JIA

The classification and clinical characteristics of juvenile idiopathic arthritis (JIA) subtypes are described as follows:

Systemic Juvenile Idiopathic Arthritis (Systemic JIA)

Systemic JIA can occur at any age but most frequently develops before the age of 5.

Fever lasts for at least 2 weeks, accompanied by one or more of the following symptoms:

- Transitory, non-fixed erythematous rash.

- Lymphadenopathy.

- Hepatomegaly and/or splenomegaly.

- Serositis, such as pleuritis or pericarditis.

The following conditions should be excluded: (i) psoriasis; (ii) arthritis in males over the age of 6 with HLA-B27 positivity; (iii) a family history of HLA-B27-related diseases, including ankylosing spondylitis, arthritis with enthesitis, acute anterior uveitis, or sacroiliitis; (iv) two positive results for rheumatoid factor (RF) taken at least 3 months apart.

Fever in this subtype generally exhibits a quotidian or spiking pattern, with daily temperature fluctuations between 37°C and 40°C. The rash typically appears or resolves in correlation with temperature changes. Joint symptoms mostly include arthralgia or arthritis, frequently involving multiple joints. The knee, wrist, and ankle joints are the most commonly affected areas. Limb muscle pain is often present and tends to worsen during febrile episodes, improving or alleviating as fever subsides. Monoarthritis is uncommon. Joint symptoms may be the initial presentation or may appear months or years after acute disease onset. Neurological symptoms in some cases may indicate macrophage activation syndrome (MAS) as a complication.

Rheumatoid Factor-Negative Polyarthritis (RF-Negative Polyarthritis)

This subtype is characterized by involvement of five or more joints within the first 6 months, with RF negativity.

The following conditions should be excluded: (i) psoriasis or a first-degree relative with a history of psoriasis; (ii) arthritis in males over the age of 6 with HLA-B27 positivity; (iii) a family history of HLA-B27-related diseases, such as ankylosing spondylitis, arthritis with enthesitis, Reiter syndrome, or acute anterior uveitis, or sacroiliitis associated with inflammatory bowel disease; (iv) two positive RF results taken at least 3 months apart; (v) systemic JIA.

This subtype can occur at any age but has two incidence peaks: ages 1–3 and 9–14. Females are more commonly affected. Involvement of five or more joints is typically symmetrical and can include both large and small joints. Temporomandibular joint involvement may cause difficulty opening the mouth and micrognathia. A younger age of onset is associated with a higher risk of ocular complications, and the long-term prognosis tends to be relatively poor. Severe arthritis develops in approximately 10%–15% of cases.

Rheumatoid Factor-Positive Polyarthritis (RF-Positive Polyarthritis)

This subtype involves five or more joints within the first 6 months, with at least two positive RF results taken at least 3 months apart.

The following conditions should be excluded: (i) psoriasis or a first-degree relative with a history of psoriasis; (ii) arthritis in males over the age of 6 with HLA-B27 positivity; (iii) a family history of HLA-B27-related diseases, including ankylosing spondylitis, arthritis with enthesitis, Reiter syndrome, acute anterior uveitis, or sacroiliitis associated with inflammatory bowel disease; (iv) systemic JIA.

This subtype is more common in females and usually manifests in late childhood, with an average age of onset between 9 and 11. Clinical manifestations are similar to those of rheumatoid arthritis (RA) in adults. Joint symptoms are more severe than in RF-negative polyarthritis, with symmetrical involvement of both large and small joints. Commonly affected joints include the metacarpophalangeal (MCP) joints, proximal interphalangeal (PIP) joints, wrists, and metatarsophalangeal joints. Without proper treatment, over 50% of patients may develop joint ankylosis, severe deformities, and disabilities in the later stages of the disease. In addition to arthritis, rheumatoid nodules can be observed in this subtype.

Oligoarthritis

Oligoarthritis is characterized by the involvement of fewer than five joints during the first six months of disease onset. This category is further divided into two subtypes: (i) Persistent oligoarthritis, in which fewer than four joints remain affected throughout the course of the disease; (ii) Extended oligoarthritis, in which the involvement of five or more joints develops after the first six months. Approximately 20% of children with oligoarthritis progress to the extended subtype.

Certain conditions require exclusion, including (i) psoriasis or a first-degree relative with psoriasis; (ii) arthritis in males over the age of 6 with HLA-B27 positivity; (iii) a family history of HLA-B27-related diseases, such as ankylosing spondylitis, arthritis with enthesitis, Reiter syndrome, acute anterior uveitis, or sacroiliitis associated with inflammatory bowel disease; (iv) two positive results for rheumatoid factor (RF) separated by at least three months; (v) systemic JIA.

This subtype predominantly affects females and typically develops before the age of 5. Large joints are most commonly involved, including the knees, ankles, elbows, and wrists. The involvement of joints is often asymmetrical. Recurring episodes of arthritis may lead to the development of unequal leg lengths. Approximately 20%–30% of affected children experience chronic uveitis, which can result in vision impairment or even blindness.

Enthesitis-Related Arthritis (ERA)

Enthesitis-related arthritis is characterized by arthritis combined with enthesitis, or arthritis or enthesitis along with at least two of the following conditions: (i) tenderness over the sacroiliac joint and/or inflammatory lumbosacral pain; (ii) HLA-B27 positivity; (iii) male gender with disease onset after the age of 6; (iv) a first-degree family history of HLA-B27-related diseases, such as ankylosing spondylitis, arthritis with enthesitis, reactive arthritis, acute anterior uveitis, or inflammatory bowel disease-associated sacroiliitis.

Exclusions include (i) psoriasis or a first-degree relative with a history of psoriasis; (ii) two positive RF results separated by at least three months; (iii) systemic JIA; (iv) arthritis meeting the criteria for two or more JIA subtypes.

This subtype is more common in males, generally manifesting after the age of 6. Arthritis in the limbs, especially large joints of the lower extremities such as the hips, knees, and ankles, is frequently the initial symptom. Symptoms include swelling, pain, and restricted movement.

Sacroiliac joint involvement can arise early in the disease course but more frequently appears months or years after onset. Typical symptoms include intermittent lower-back pain, which may later become persistent over time. Pain can radiate to the buttocks or thighs. Tenderness over the sacroiliac joint is detected with direct palpation. As the disease progresses, spinal involvement may lead to restricted movement of the lumbar region. Severe cases may cause alterations affecting the thoracic and cervical spine, resulting in ankylosis of the entire spine. In some children, early imaging findings of sacroiliitis may appear without clinical symptoms or signs. Acute recurrent uveitis may occur, and inflammation at the insertion of the Achilles tendon and/or plantar fascia into the calcaneus may lead to heel pain. Approximately 90% of individuals with this subtype exhibit HLA-B27 positivity, often with a positive family history.

Psoriatic Juvenile Idiopathic Arthritis (PsJIA)

Psoriatic juvenile idiopathic arthritis involves arthritis in one or more joints along with psoriasis or arthritis combined with at least two of the following features: (i) dactylitis; (ii) nail pitting or onycholysis; (iii) first-degree family history of psoriasis.

Exclusions include (i) arthritis in males over the age of 6 with HLA-B27 positivity; (ii) first-degree family history of HLA-B27-related diseases, such as ankylosing spondylitis, arthritis with enthesitis, acute anterior uveitis, or inflammatory bowel disease-associated sacroiliitis; (iii) two positive RF results separated by at least three months; (iv) systemic JIA; (v) arthritis meeting criteria for more than two JIA subtypes.

This subtype is rare in childhood and is more common in females, with a female-to-male ratio of approximately 2.5:1. It involves the asymmetrical involvement of one or several joints. More than half of affected children exhibit distal interphalangeal joint involvement and nail pitting. Arthritis can occur before, during, or years after the onset of psoriasis, with 40% of cases showing a family history of psoriasis. Sacroiliitis or ankylosing spondylitis also occurs in some patients, where HLA-B27 positivity is observed.

Undifferentiated Arthritis

Undifferentiated arthritis does not fit the criteria for any of the aforementioned subtypes or satisfies the criteria for more than two JIA subtypes.

Diagnosis and Differential Diagnosis

Supportive Diagnosis

No laboratory test is definitive for diagnosis, but certain tests can help assess disease severity and exclude other conditions.

Evidence of Inflammatory Response

Erythrocyte sedimentation rate (ESR) is markedly elevated in many cases, although it is often normal in oligoarthritis patients. In cases of polyarthritis and systemic JIA, acute-phase reactants (C-reactive protein, IL-1, and IL-6, etc.) are elevated, providing useful information about disease activity during follow-up.

Autoantibodies

Rheumatoid Factor (RF)

Positive RF suggests more severe joint involvement. In RF-negative cases, hidden RF can be detected in over one-third of patients using enzyme-linked immunoassays. This can aid in the diagnosis and prognosis of JIA.

Anti-Cyclic Citrullinated Peptide (ACCP) Antibodies

ACCP is an enzyme that promotes citrullination and has increased activity in arthritis. Positive ACCP antibodies are associated with joint damage and indicate a poor prognosis.

Antinuclear Antibodies (ANA)

ANA is detected in approximately 40% of JIA patients, typically at low to moderate titers. ANA-positive patients often show characteristics such as early onset, female predominance, asymmetric arthritis, and an increased risk of uveitis.

Other Tests

Synovial Fluid Analysis and Synovial Biopsy

These tests assist in distinguishing JIA from conditions such as septic arthritis, tuberculous arthritis, sarcoidosis, and synovial tumors.

Complete Blood Count (CBC)

Mild to moderate anemia is common. Elevated total white blood cell count and neutrophils may be observed. Systemic JIA may present with a leukemoid reaction.

X-ray

In the first year of disease, X-rays typically show only soft tissue swelling. As the disease progresses, periarticular osteoporosis, periosteal thickening near the joints, and, in advanced stages, joint surface destruction (commonly in the wrist joints) may develop.

Other Imaging Studies

Doppler ultrasound and MRI of bones and joints help detect early bone and joint damage.

Diagnostic Criteria

The diagnosis of JIA primarily relies on clinical presentation and exclusion of other conditions.

Definition

Joint swelling of unknown cause in children under 16 years of age, persisting for more than six weeks, may suggest a diagnosis of juvenile idiopathic arthritis. Diseases listed under differential diagnosis must be excluded.

Classification

Classification follows the subtype definitions of JIA, with attention given to the specific exclusion criteria for each subtype.

Differential Diagnosis

For cases dominated by systemic symptoms such as high fever and rashes, the following conditions need to be considered:

- Systemic Infections: Sepsis, tuberculosis, viral infections, etc.

- Neoplastic Diseases: Leukemia, lymphoma, histiocytic malignancies, or other malignant tumors.

For cases primarily involving joint involvement, differentiation from the following conditions is necessary:

- Rheumatic arthritis.

- Septic arthritis.

- Tuberculous arthritis.

- Traumatic arthritis.

For cases involving arthritis in conjunction with other rheumatic diseases, differentiation is required from conditions such as:

- Systemic lupus erythematosus (SLE).

- Mixed connective tissue disease (MCTD).

- Henoch-Schönlein purpura (HSP).

- Kawasaki disease (KD).

Additional differentiation is needed for diseases such as:

- Spinal cord tumors, lumbar infections, intervertebral disc abnormalities, congenital hip disorders.

- Inflammatory bowel diseases (e.g., ulcerative colitis, localized enteritis).

- Psoriasis or Reiter syndrome with coexisting spondylitis.

Treatment

Principles of Treatment

The primary goals of treatment include controlling disease activity, alleviating or eliminating fever and joint swelling/pain, preventing joint dysfunction and disability, restoring joint function, and improving the patient’s ability to engage in daily activities.

General Treatment

Excessive bed rest is generally not recommended, except during acute febrile episodes. Psychological support for patients can help address low self-esteem caused by chronic illness or disability, strengthen their confidence in overcoming the disease, and encourage appropriate levels of physical activity and school attendance. Involvement of caregivers, social workers, schools, and community groups can facilitate the patient’s reintegration into society and promote overall physical and mental well-being. Regular ophthalmology follow-ups are suggested for early detection of uveitis.

Pharmacological Treatment

Nonsteroidal Anti-Inflammatory Drugs (NSAIDs)

Naproxen is recommended at a dose of 10–15 mg/kg per day, divided into two doses, or ibuprofen at 50 mg/kg per day, divided into two or three doses. Symptomatic relief is usually achieved within 1–2 weeks, after which the dose is gradually reduced. Long-term maintenance involves the lowest clinically effective dose, and medication is typically discontinued within 3–6 months. Adverse reactions may include gastrointestinal discomfort, liver or kidney dysfunction, and allergic reactions. Aspirin is now less commonly used due to concerns over long-term side effects. Other NSAIDs, such as diclofenac sodium, are options for treatment. The simultaneous use of multiple NSAIDs is generally not advised to avoid severe gastrointestinal side effects.

Disease-Modifying Anti-Rheumatic Drugs (DMARDs)

DMARDs, also referred to as slow-acting anti-rheumatic drugs (SAARDs), are used early after diagnosis, ideally before the occurrence of joint erosion or destruction, to effectively control disease progression.

Methotrexate (MTX) is administered at 10–15 mg/m2 once weekly, with a maximum dose of 20 mg/m² per week. Treatment usually begins to show effect within 3–12 weeks. Side effects include gastrointestinal discomfort, transient increases in liver enzymes, gastritis, oral ulcers, anemia, and granulocytopenia, which are generally mild. Long-term use requires monitoring for potential tumor formation risks.

Hydroxychloroquine serves as adjunct therapy for children above the age of 6, at a dose of 5–6 mg/(kg·day), not exceeding 0.4 g/day, taken in one or two doses. Treatment duration ranges from 3 months to 1 year. Adverse effects may include retinitis, leukopenia, muscle weakness, and liver dysfunction. Regular ophthalmological checks every 3–6 months are recommended.

Sulfasalazine is initiated at 40–60 mg/(kg·day). Effects are generally observed within 1–2 months, with maintenance doses of 30 mg/(kg·day). Side effects include nausea, vomiting, rash, asthma, anemia, hemolysis, bone marrow suppression, and hepatotoxicity. The medication is contraindicated in individuals allergic to sulfonamides or children under 2 years of age.

Other DMARDs, such as D-penicillamine and gold preparations, are less commonly used due to significant adverse effects.

Corticosteroids

Corticosteroids reduce symptoms of JIA arthritis but do not prevent joint damage and are associated with significant long-term side effects. They are not the first-line drug choice and should only be used when strictly indicated:

Systemic JIA

For cases unresponsive to NSAIDs, prednisone at 0.5–1 mg/(kg·day) (up to 60 mg/day) may be administered as a single dose or divided doses, with tapering off after fever resolution. Severe complications such as polyserositis, interstitial lung disease, or macrophage activation syndrome (MAS) may require intravenous methylprednisolone at high doses.

Polyarthritis

For severe cases unresponsive to NSAIDs and DMARDs, small doses of prednisone may be used short-term to relieve symptoms and improve quality of life.

Oligoarthritis

Systemic corticosteroids are generally not recommended; betamethasone or hydrocortisone suspensions may be injected into affected joints after synovial fluid aspiration for localized treatment.

Uveitis

Mild cases may respond to mydriatics and corticosteroid eye drops. For patients with severe vision impairment, low-dose prednisone may be added. High doses of corticosteroids are not recommended for PsJIA.

Other Immunosuppressive Agents

Based on JIA subtype, agents such as cyclosporine A, cyclophosphamide, leflunomide, azathioprine, and triptolide glycosides may be used, with monitoring for effectiveness and adverse events.

Biologic Agents

Monoclonal antibodies targeting tumor necrosis factor-alpha (TNF-α) are effective for polyarthritis, while interleukin-6 (IL-6) antagonists show significant anti-inflammatory effects for systemic JIA. Combining biologics with conventional DMARDs often improves therapeutic outcomes.

Other Therapies

High-dose intravenous immunoglobulin (IVIG) for refractory systemic JIA has not gained widespread recognition. Purified herbal formulations like total glucosides of paeony show potential efficacy in treating JIA.

Physical Therapy

Physical therapy is crucial to maintaining joint mobility and muscle strength in JIA patients. Early intervention to preserve joint function and prevent muscle atrophy is associated with improved outcomes and reduced risk of disability.

Prognosis

The overall prognosis for JIA is favorable, but there is significant heterogeneity depending on subtype. Complications predominantly include loss of joint function and vision impairment due to uveitis. JIA tends to recur, and occasional relapses into adult life may occur after years of remission. High titers of anti-ACCP and IgM RF are associated with poorer prognoses.

Systemic JIA may be complicated by MAS, characterized clinically by fever, hepatosplenomegaly, lymphadenopathy, pancytopenia, acute liver dysfunction, coagulopathy, and central nervous system involvement, and in severe cases, acute lung injury and multiorgan failure. Laboratory findings include elevated serum ferritin and transaminase levels, increased lipids, reduced ESR, as well as low albumin and fibrinogen levels. Bone marrow biopsy may reveal hemophagocytosis. MAS usually presents acutely, progresses rapidly, and carries a high mortality rate. Its mechanism involves overactivation of T lymphocytes and macrophages, leading to excessive cytokine production. MAS predominantly occurs in systemic JIA but has also been reported in small numbers in polyarthritis and oligoarthritis cases.