Rheumatic fever (RF) is an acute or chronic rheumatic disease that occurs following an infection with Group A beta-hemolytic streptococci. It can recur and primarily affects the joints, heart, skin, and subcutaneous tissues, while occasionally involving the central nervous system, blood vessels, serous membranes, lungs, kidneys, and other organ systems. The clinical manifestations are mainly arthritis and carditis, often accompanied by fever, rashes, subcutaneous nodules, and chorea. The disease tends to be self-limiting. Acute episodes typically present with pronounced fever, rash, and arthritis, while residual heart damage of varying severity often remains after the acute phase. Valve damage is particularly notable, potentially leading to chronic rheumatic heart disease or rheumatic valvular disease. The condition can occur at any age but is most common in children and adolescents aged 5–15 years. It is rare in infants under the age of three. There are no gender differences in prevalence, and cases can occur throughout the year, although the disease is more frequent in winter and spring.

The incidence and severity of rheumatic fever have declined significantly, but in certain developing countries, rheumatic fever and rheumatic heart disease remain prevalent.

Etiology and Pathogenesis

Etiology

Rheumatic fever is a late complication of pharyngitis caused by Group A beta-hemolytic streptococci. Among children with streptococcal pharyngitis, approximately 0.3–3% develop rheumatic fever 1–4 weeks after infection. Infections caused by streptococci at other sites, such as the skin, do not lead to rheumatic fever. Factors influencing the onset of the disease include:

- Extended persistence of the streptococci in the pharynx increases the likelihood of disease development.

- Infection with specific rheumatogenic strains of Group A streptococci, such as M serotypes (types 1–48) and mucoid strains.

- The genetic predisposition of the affected individual, as certain populations exhibit higher susceptibility.

Pathogenesis

Molecular Mimicry

Group A beta-hemolytic streptococci exhibit complex antigenicity. The molecular structures of various streptococcal antigens display homology to antigens found in human tissues. Immune responses against streptococci may trigger cross-reactive immune reactions with human tissues, leading to organ damage. This molecular mimicry is considered the primary mechanism behind rheumatic fever. Examples of cross-reactive antigens include:

- Hyaluronic acid in the streptococcal capsule shares common antigens with human joints and synovial membranes.

- M protein and M-related proteins in the outer layer of the streptococcal cell wall, as well as N-acetylglucosamine and rhamnose in the middle polysaccharide layer, share common antigens with human myocardium and cardiac valves.

- Lipoproteins in the streptococcal cell membrane share common antigens with myocardial membranes and the subthalamic and caudate nuclei of the human brain.

Autoimmune Responses

Autoimmune responses triggered by molecular mimicry between streptococci and human tissues contribute to disease development.

- Immune Complex Disease: Autoantigens generated from streptococcal antigen mimicry can bind to anti-streptococcal antibodies, forming circulating immune complexes that deposit in synovial membranes, myocardium, and cardiac valves. These immune complexes activate complement components, leading to inflammatory lesions.

- Abnormal Cell-Mediated Immune Responses:

- Peripheral blood lymphocytes in affected individuals exhibit enhanced proliferative responses to streptococcal antigens. T lymphocytes demonstrate cytotoxic effects on myocardial cells.

- Peripheral leukocyte mobility inhibition tests induced by streptococcal antigens show enhanced results in affected patients, while lymphocyte proliferative responses decrease, and natural killer cell function increases.

- Monocytes in affected individuals display abnormal immune responses to streptococcal antigens.

Toxin Production

Group A streptococci can produce multiple exotoxins and enzymes that may exert toxic effects on human myocardium and joints.

Genetic Background

Associations with HLA-B35, HLA-DR2, HLA-DR4, and lymphocyte surface markers such as D8/17+ have been reported in relation to rheumatic fever. However, whether the disease follows a multigenic inheritance pattern or involves specific susceptibility genes remains uncertain.

Pathology

Acute Exudative Phase

During this phase, connective tissues in affected areas, such as the heart, joints, and skin, undergo edema and degeneration, with infiltration by lymphocytes and plasma cells. Fibrinous exudates accumulate on the pericardium, and serous effusions appear in the joint cavities. This phase typically lasts about one month.

Proliferative Phase

This phase predominantly affects the myocardium and endocardium, including cardiac valves. A characteristic feature is the formation of Aschoff bodies, consisting of collagen fibrin-like necrotic material at the center surrounded by lymphocytes, plasma cells, and multinucleated giant cells (rheumatic cells). Rheumatic cells are round or oval, with abundant basophilic cytoplasm and prominent nucleoli. Aschoff bodies can also appear in muscles and connective tissues, particularly in subcutaneous tissue and tendon sheaths near joints, forming subcutaneous nodules. These nodules are both clinical and pathological indicators of rheumatic activity. This phase lasts approximately 3–4 months.

Sclerotic Phase

In this phase, necrotic material in Aschoff bodies undergoes absorption, with decreased inflammation and increased proliferation of fibrous tissue, leading to scar formation. Cardiac valve edges may develop eosinophilic verrucous lesions, and the valves thicken and scar. The mitral valve is most commonly affected, followed by the aortic valve, with the tricuspid valve rarely involved. This phase lasts about 2–3 months. Additionally, scattered nonspecific cellular degeneration and hyaline degeneration of small blood vessels may be observed in the cerebral cortex, cerebellum, and basal ganglia.

Clinical Manifestations

Rheumatic fever often presents with an acute onset but may sometimes follow an insidious course. A history of streptococcal pharyngitis is commonly observed 1–6 weeks before the onset of acute rheumatic fever, with symptoms such as fever, sore throat, submandibular lymphadenopathy, and cough. The classic presentation of rheumatic fever includes five major manifestations: migratory polyarthritis, carditis, subcutaneous nodules, erythema marginatum, and chorea. These manifestations may occur individually or simultaneously. Fever and arthritis are the most frequent complaints. Skin and subcutaneous manifestations are less common in children with rheumatic fever, typically appearing in those who have already developed arthritis, chorea, or carditis.

General Manifestations

Patients with acute onset often experience fever ranging from 38°C to 40°C, with an irregular fever pattern that transitions to low-grade fever within 1–2 weeks. Those with an insidious onset may exhibit only low-grade fever or no fever at all. Other symptoms include lethargy, fatigue, poor appetite, pallor, excessive sweating, joint pain, and abdominal pain. Rare cases may present with pleuritis and pneumonia. An untreated acute episode of rheumatic fever usually lasts no more than six months. Without preventive treatment, recurrent episodes may occur.

Carditis

Involvement of the heart occurs in approximately 40–50% of patients and represents the only persistent organ damage caused by rheumatic fever. Symptoms of carditis generally appear within 1–2 weeks after the first episode of rheumatic fever. Initial episodes most commonly present with myocarditis and endocarditis, though involvement of the myocardium, endocardium, and pericardium together constitutes pancarditis.

Myocarditis

Mild cases may be asymptomatic, while severe cases may result in varying degrees of heart failure. Tachycardia disproportionate to fever is often observed. Cardiomegaly and diffuse apical impulse might occur. Heart sounds may be muffled, and a gallop rhythm may be heard. A mild systolic murmur, described as blowing in quality, may be heard at the apex. Approximately 75% of initial cases exhibit a mid-diastolic murmur at the aortic valve area. Chest X-rays may reveal an enlarged heart with weakened pulsation. Electrocardiograms often display prolonged PR intervals, along with T-wave flattening and ST-segment abnormalities or arrhythmias.

Endocarditis

This predominantly affects the mitral and/or aortic valves, leading to valvular regurgitation. Mitral regurgitation is characterized by a Grade II–III/VI holosystolic blowing murmur at the apex, sometimes radiating to the axilla. A mid-diastolic murmur due to relative mitral stenosis can sometimes be detected. Aortic regurgitation is marked by an early diastolic decrescendo murmur along the left sternal border at the third intercostal space. Acute-phase valvular damage often manifests as hyperemia and edema, which may diminish during recovery. Recurrent episodes can lead to permanent scarring of the heart valves, resulting in rheumatic valvular disease. Echocardiography can more sensitively detect subclinical valvular inflammation in patients with no audible murmurs on physical examination.

Pericarditis

Symptoms may include precordial pain, and in some cases, a pericardial friction rub can be auscultated at the base of the heart. Signs of pericardial tamponade, such as jugular venous distention and hepatomegaly, may appear. When the pericardial effusion is small, it may not be detected clinically, whereas large pericardial effusions may lead to the absence of precordial pulsation and muffled heart sounds. Chest X-rays may reveal a flask-shaped cardiac silhouette due to bilateral enlargement. Electrocardiograms may show low voltage and early ST-segment elevation, followed by a return to baseline with subsequent T-wave changes. Pericardial effusion can also be identified on echocardiography. Clinical manifestations of pericarditis typically indicate severe carditis and may predispose to congestive heart failure.

Congestive heart failure occurs in approximately 5–10% of children during the initial episode of rheumatic carditis, with an increased rate of occurrence during subsequent episodes. The presence of heart failure in children with rheumatic valvular disease suggests active carditis.

Arthritis

Arthritis is present in 50–60% of cases of acute rheumatic fever, with the hallmark being migratory polyarthritis. It most commonly affects large joints such as the knees, ankles, elbows, and wrists. Involved joints exhibit redness, swelling, heat, pain, and limited range of motion. Symptoms in each affected joint typically resolve within a few days without leaving deformities, although new joints may subsequently become involved, continuing the migratory progression for 3–4 weeks.

Chorea

Chorea occurs in 3–10% of cases and is also known as Sydenham chorea. It presents as involuntary, rapid movements of the whole body or specific muscle groups, such as grimacing, tongue protrusion, shoulder shrugging, and uncoordinated fine motor movements. Speech difficulties, writing impairment, and exaggeration of movements with emotional excitement or concentration may also occur, while symptoms disappear during sleep. Weakness and emotional instability are common. Chorea typically manifests weeks to months after other symptoms have appeared, though it may be an initial symptom in milder cases of rheumatic fever. The duration of chorea ranges from 1–3 months, but rare cases may suffer recurrent episodes over 1–2 years. In rare instances, neurological or psychiatric sequelae, such as personality changes, migraines, or fine motor incoordination, may persist.

Skin Manifestations

Erythema Marginatum

This occurs in approximately 6–25% of cases. It is characterized by pale red, annular, or semi-annular lesions with clear edges and central pallor. These lesions vary in size and are primarily located on the trunk and proximal limbs. They tend to be transient, fluctuant, and migratory, persisting for several weeks in some instances.

Subcutaneous Nodules

These are present in 2–16% of cases and are often associated with severe carditis. These nodules are firm, painless, and non-adherent to the overlying skin, measuring 0.1–1 cm in diameter. They are most commonly found on the extensor surfaces of joints (elbows, knees, wrists, ankles), as well as on the occipital scalp, forehead, chest, and spinous processes of the vertebrae. They typically resolve within 2–4 weeks.

Auxiliary Examinations

Evidence of Streptococcal Infection

About 20–25% of pediatric patients with rheumatic fever yield positive results for Group A beta-hemolytic streptococci in throat swab cultures. Serum anti-streptolysin O (ASO) titers begin to rise approximately one week after streptococcal infection and gradually decline after two months. Elevated ASO levels are observed in 50–80% of patients with rheumatic fever. When additional tests for anti-deoxyribonuclease B (anti-DNase B), anti-streptokinase (ASK), and anti-hyaluronidase (AH) are conducted, the positive rate can increase to approximately 95%.

Indices of Rheumatic Fever Activity

Indices reflecting disease activity include elevated peripheral white blood cell counts, increased levels of neutrophils, accelerated erythrocyte sedimentation rate (ESR), elevated C-reactive protein (CRP), and increased α2-globulin and mucoprotein concentrations. These parameters indicate active disease but are not specific for diagnosing rheumatic fever.

Diagnosis and Differential Diagnosis

Jones Diagnostic Criteria

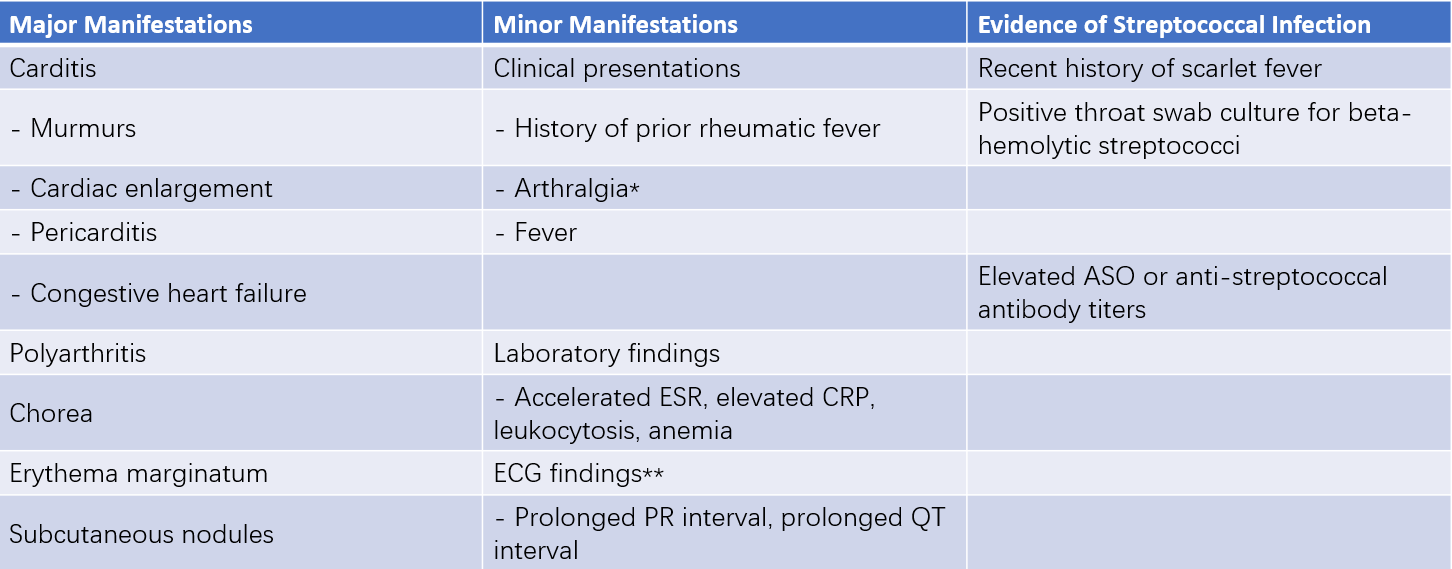

The diagnosis of rheumatic fever relies on a comprehensive assessment of clinical manifestations and laboratory findings. The revised 1992 Jones criteria include three components:

- Major criteria

- Minor criteria

- Evidence of streptococcal infection

Table 1 Revised Jones diagnostic criteria

Notes:

If arthritis has been categorized as a major manifestation, arthralgia cannot simultaneously be considered a minor manifestation.

If carditis has been classified as a major manifestation, ECG findings cannot concurrently serve as a minor manifestation.

A highly probable diagnosis of acute rheumatic fever is suggested in cases where evidence of prior streptococcal infection exists alongside either two major manifestations or one major manifestation plus two minor manifestations.

In the following three scenarios, rigid adherence to the above diagnostic criteria is not required:

- Chorea as the sole clinical manifestation.

- Insidious or slowly progressive onset of carditis.

- Patients with a history of rheumatic fever or existing rheumatic heart disease who face an elevated risk of rheumatic fever recurrence upon reinfection with Group A streptococci.

A diagnosis of rheumatic fever requires evidence of streptococcal infection and the presence of either two major criteria or one major criterion accompanied by two minor criteria. Due to an increased prevalence of atypical and mild cases in recent years, the World Health Organization (WHO) updated its diagnostic criteria for rheumatic fever in 2002–2003 to include important modifications:

For recurrent rheumatic fever in patients with rheumatic heart disease, the diagnostic threshold was lowered, requiring only two minor criteria and evidence of preceding streptococcal infection.

For patients with insidious-onset rheumatic carditis and chorea, a diagnosis can be established even in the absence of other major criteria or evidence of preceding streptococcal infection.

Greater emphasis was placed on the potential progression of polyarthritis, polyarthralgia, or monoarthritis into rheumatic fever, aiming to reduce the risks of misdiagnosis and missed diagnoses.

Following confirmation of rheumatic fever, effort is made to specify the clinical subtype and determine the presence of cardiac involvement. For patients with a history of rheumatic fever, it is especially important to ascertain whether there is active disease.

Differential Diagnosis

Rheumatic fever must be distinguished from several other conditions:

Differential Diagnosis for Rheumatic Arthritis

Juvenile Idiopathic Arthritis

This condition frequently involves small joints of the fingers and toes or larger joints without a migratory pattern. It often displays symmetrical joint involvement and leaves varying degrees of joint deformities after recurrent episodes. Radiographic findings include joint surface damage, narrowed joint spaces, and adjacent bone osteoporosis.

Acute Septic Arthritis

Typically, this reflects localized manifestations of systemic sepsis. Symptoms of infection and poisoning are severe, often involving large joints. It is characterized by single-joint involvement with redness, swelling, heat, pain, and limited motion. Positive blood cultures may reveal Staphylococcus aureus or other causative organisms.

Acute Leukemia

In addition to fever and bone or joint pain, symptoms of anemia, bleeding tendencies, hepatosplenomegaly, and lymphadenopathy are often present. Peripheral blood smears typically show immature white blood cells, and bone marrow examinations assist in differentiation.

Growing Pains

Pain primarily occurs in the lower extremities, often worsening at night or during sleep. It improves with massage, and no redness or swelling is observed locally.

Differential Diagnosis for Rheumatic Carditis

Infective Endocarditis

In cases of congenital heart disease or rheumatic heart disease complicated by infective endocarditis, differentiation from active rheumatic heart disease can be challenging. Features such as anemia, splenomegaly, petechiae, or embolic symptoms aid in diagnosis. Positive blood cultures and echocardiographic findings of vegetations on the valves or endocardium provide definitive evidence.

Viral Myocarditis

Differentiating simple rheumatic myocarditis from viral myocarditis is difficult. Viral myocarditis typically presents with acute onset, minimal cardiac murmurs, and low rates of endocarditis. Premature ventricular contractions and other arrhythmias are common. Laboratory tests often reveal evidence of viral infection.

Treatment

The treatment goals for rheumatic fever focus on protecting cardiac function, improving quality of life, and addressing the underlying condition. Specific measures include eliminating streptococcal infections and their triggers, managing clinical symptoms to alleviate carditis, arthritis, chorea, and other manifestations, reducing patient discomfort, addressing complications to improve quality of life, and prolonging survival.

Rest

The duration of bed rest depends on the degree of cardiac involvement and the state of cardiac function. In cases without carditis during the acute phase, bed rest is recommended for two weeks, followed by gradual resumption of activities to achieve normal activity levels within 2–4 weeks. For patients with carditis but no heart failure, bed rest is suggested for four weeks, with gradual activity resumption over 4–8 weeks. Patients with carditis accompanied by congestive heart failure require at least eight weeks of bed rest, followed by gradual increases in activity over 2–3 months.

Eliminating Streptococcal Infection

Intramuscular administration of 800,000 units of penicillin twice daily for two weeks is considered effective in eradicating streptococcal infection. Patients with penicillin allergies may use other effective antibiotics, such as macrolide antibiotics.

Anti-Rheumatic Fever Therapy

Early administration of glucocorticoids is recommended for carditis. Prednisone is used at a daily dose of 2 mg/kg, with a maximum dose of ≤60 mg/day, administered in divided doses. Gradual tapering begins after 2–4 weeks, with a total treatment duration of 8–12 weeks. For children without carditis, nonsteroidal anti-inflammatory drugs such as aspirin are used at a daily dose of 80–100 mg/kg, with a maximum dose of ≤3 g/day, administered in divided doses. Dosage tapering begins after two weeks, with a total treatment duration of 4–8 weeks.

Additional Treatments

Recurrence of congestive heart failure is considered indicative of carditis relapse, and prompt intravenous administration of high-dose glucocorticoids, such as methylprednisolone, is required. Methylprednisolone is given once daily at 10–30 mg/kg for 1–3 administrations, with heart failure control achieved in most cases within 2–3 days. Digitalis should be used cautiously or avoided to prevent digitalis toxicity. A low-sodium diet is recommended, and oxygen inhalation, diuretics, and vasodilators may be provided as necessary. For chorea, sedatives such as phenobarbital or diazepam can be administered. Immobilization is advised for joint swelling and pain, with gradual resumption of movement after symptom improvement.

Prevention and Prognosis

The prognosis of rheumatic fever is primarily influenced by the severity of carditis, the adequacy of initial anti-rheumatic treatment, and proper antibiotic management of streptococcal infections. Carditis is associated with a high risk of recurrence and a poorer prognosis, particularly in severe cases with congestive heart failure.

Prophylactic measures for rheumatic fever include intramuscular injection of benzathine penicillin (long-acting penicillin) every 3–4 weeks. Patients weighing less than 27 kg may receive 600,000 units, and those weighing 27 kg or more are advised to receive 1.2 million units. The prophylactic regimen should last for at least five years and, ideally, continue until age 25. For patients with established rheumatic heart disease, lifelong prophylactic medication is recommended. Penicillin-allergic patients may use oral erythromycin for 6–7 days each month, following the same duration guidelines as non-allergic patients.

Children with rheumatic fever or rheumatic heart disease undergoing dental procedures or other surgeries require prophylactic antibiotics before and after surgery to prevent infective endocarditis.