Neonatal necrotizing enterocolitis (NEC) is an acquired inflammatory syndrome of the intestine characterized by intestinal wall inflammation and coagulative necrosis. It primarily presents with abdominal distension, vomiting, and bloody stools, with radiographic features that include pneumatosis intestinalis and portal venous gas. NEC is a life-threatening disease in neonates. It occurs in 90% of preterm infants but can also develop in full-term infants. The risk of NEC is inversely related to gestational age, with smaller gestational ages associated with higher risk.

Etiology and Pathogenesis

The etiology and pathogenesis of NEC are highly complex and not yet fully understood, likely involving the interplay of multiple factors.

Prematurity

Prematurity is an independent and significant risk factor for NEC. Immature intestinal barrier function, reduced gastric acid secretion, poor gastrointestinal motility, low enzymatic activity, and increased mucosal permeability contribute to intestinal mucosal injury in the context of inappropriate feeding, infection, or ischemia. Additionally, immaturity of gut-associated immune function, including reduced secretory IgA production, facilitates bacterial invasion and proliferation within the intestinal wall.

Intestinal Hypoxia and Ischemia

Conditions that cause hypoxia and ischemia, such as perinatal asphyxia, severe apnea, critical cardiopulmonary disease, shock, twin–twin transfusion syndrome, polycythemia, or maternal cocaine abuse during pregnancy, may lead to intestinal mucosal injury secondary to ischemia and hypoxia.

Infection

Infection is considered one of the primary causes of NEC. Pathogenic microorganisms or their toxins in cases of sepsis, enteritis, or other severe infections can directly damage the mucosa or activate immune cells to produce cytokines, which then contribute to the development of NEC. Furthermore, excessive gas production in the intestines due to bacterial colonization can lead to distended loops of bowel and mucosal injury. Common pathogens include Klebsiella pneumoniae, Escherichia coli, Clostridium species, Streptococcus species, Lactobacillus species, Enterococcus species, and coagulase-negative staphylococci.

Disruption of Intestinal Microbial Ecology

In preterm or ill neonates, delayed feeding and prolonged exposure to broad-spectrum antibiotics may interfere with the establishment of normal gut microbiota. Colonization by pathogens or dominance of particular species in the gut may lead to their excessive proliferation, intestinal invasion, and subsequent mucosal injury.

Other Factors

The high osmolarity (greater than 400 mmol/L) of certain infant formulas and medications, such as vitamin E, theophylline, and indomethacin, has been associated with NEC. There are also reports suggesting that high-dose intravenous immunoglobulin therapy or transfusions of packed red blood cells could increase the risk of NEC.

Pathology

The severity of intestinal lesions varies widely. In mild cases, the affected area may span only a few centimeters, while in severe cases, the entire intestine can be involved. The most commonly affected regions are the terminal ileum and proximal colon. The intestinal lumen exhibits distension with gas, and the mucosa may show patchy or extensive necrosis. Gas accumulation, hemorrhage, and necrosis of varying degrees are seen in the intestinal wall. In severe cases, full-thickness necrosis of the intestinal wall can result in perforation.

Clinical Manifestations

NEC predominantly affects preterm infants, with the onset timing related to gestational age. Full-term infants often present within the first week of life, while preterm infants typically develop symptoms in the second to third week. On average, NEC occurs around a corrected gestational age of 30–32 weeks. Extremely low birth weight infants can present as late as two months of age.

Systemic Symptoms

Systemic findings are nonspecific and may include respiratory distress, apnea, lethargy, temperature instability, and feeding intolerance. Severe cases may exhibit bleeding, hypotension, shock, seizures, and disturbances in water and electrolyte balance.

Gastrointestinal Symptoms

The hallmark symptoms of NEC are abdominal distension, vomiting, and bloody stools. Initial signs often include increased gastric residuals, abdominal distension, and vomiting, indicative of feeding intolerance. Over time, stool consistency changes, with bloody stools becoming apparent. Physical examination may reveal visible bowel loops and abdominal wall erythema. Some cases show right lower quadrant muscle rigidity and tenderness, along with reduced or absent bowel sounds. Severe cases may progress to peritonitis and perforation.

Auxiliary Examinations

Laboratory Tests

Complete Blood Count (CBC)

Findings may include increased or decreased white blood cell (WBC) count, elevated proportion of band neutrophils, and thrombocytopenia.

Inflammatory Markers

Procalcitonin and C-reactive protein levels may be elevated, though they can remain normal in early stages.

Blood Gas Analysis and Electrolyte Monitoring

Findings may indicate metabolic acidosis and electrolyte imbalances.

Stool Tests

Routine stool examination often shows occult blood positivity, and in some cases, bacterial culture or tests for intestinal rotavirus are positive.

Other Findings

Abnormal blood glucose levels (hypoglycemia or hyperglycemia), coagulation dysfunction, and positive blood culture are especially helpful for diagnosis.

Biomarkers

Biomarkers such as fatty acid-binding protein, intestinal trefoil factor, β-glucosidase, and fecal calprotectin may reflect intestinal inflammation and epithelial injury; however, these have not been widely adopted in clinical practice and require further research.

Abdominal Imaging

Imaging studies are important for diagnosis. Both frontal and lateral X-rays are clinically valuable and are recommended at intervals of 6–8 hours initially, followed by 12–24 hours, until normalization.

- Findings suggestive of NEC: Imaging may show bowel wall thickening and intestinal distension.

- Definitive NEC: Radiologic evidence includes pneumatosis intestinalis, portal venous gas, or free intraperitoneal air indicative of bowel perforation.

Figure 1 Radiographic appearance of pneumatosis intestinalis in NEC

Figure 2 Radiographic appearance of portal venous gas in NEC

Bowel perforation often occurs within 48–72 hours after the appearance of pneumatosis intestinalis or portal venous gas, so close observation with 6–8 hour imaging intervals is critical during this period. Serial imaging can be discontinued 48–72 hours after clinical improvement.

Abdominal Ultrasound

Advances in ultrasound resolution, particularly the use of high-frequency probes, allow dynamic assessment of bowel wall thickness, intramural gas, intestinal peristalsis, blood supply to the intestinal wall, and the presence of intra-abdominal masses or adhesions. Reports indicate that ultrasound has higher sensitivity for detecting portal venous gas and pneumatosis intestinalis compared to X-rays.

Diagnosis

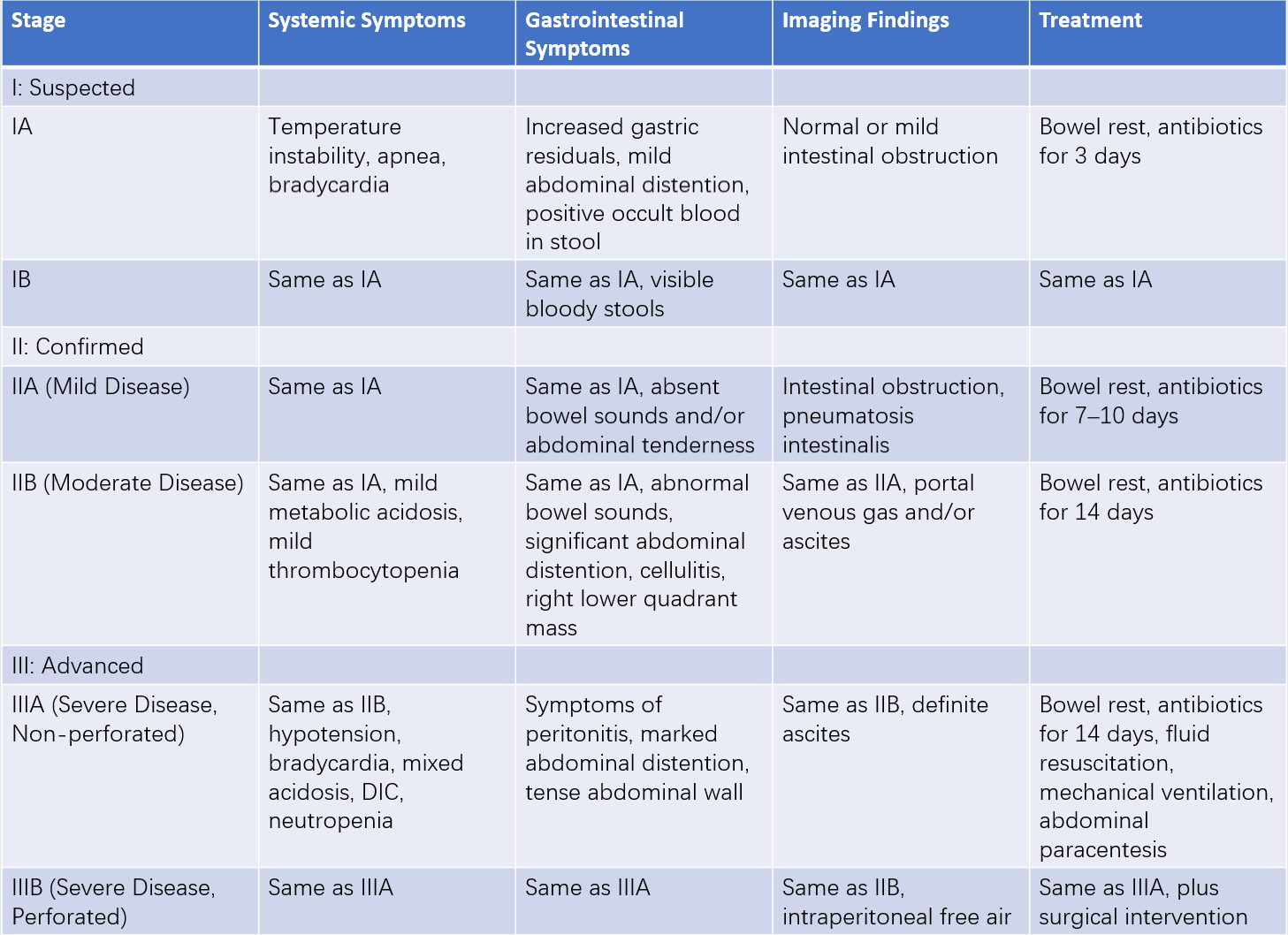

The diagnosis of NEC is straightforward in typical cases, particularly in preterm infants who exhibit feeding intolerance, abdominal distension, vomiting, and bloody stools, in conjunction with characteristic abdominal X-ray findings. However, in cases with insidious onset or nonspecific clinical signs, distinction from other conditions is necessary. The modified Bell staging criteria are commonly used in clinical settings to classify the severity of NEC.

Table 1 Revised Bell staging criteria for NEC

Treatment

Bowel Rest

Complete cessation of oral feeding and gastrointestinal decompression is required, with durations varying by stage: 72 hours for stage I, 7–10 days for stage II, and 14 days or longer for stage III. Gradual reintroduction of oral feeding can be considered once clinical symptoms improve, occult blood in stool becomes negative, and abnormal radiologic findings resolve.

Antibiotics

Empirical antibiotics often include ampicillin, piperacillin, or third-generation cephalosporins. Antibiotics should be adjusted based on culture and sensitivity results if blood cultures are positive. For anaerobic infections, metronidazole is recommended, while vancomycin may be used for enterococcal infections. The duration of antibiotic therapy depends on the severity of disease, generally 7–10 days for mild cases and 14 days or longer for severe cases.

Supportive Care

Removal of umbilical artery and venous catheters may be necessary.

Long-term intravenous fluid therapy is provided through peripherally inserted central catheters (PICC) or peripheral veins. Daily fluid administration is typically in the range of 120–150 ml/kg, with adjustments based on gastrointestinal losses.

Total parenteral nutrition is essential during prolonged periods of feeding cessation, ensuring an energy intake of 378–462 kJ/kg (90–110 kcal/kg) per day.

Fresh frozen plasma may be administered for coagulation abnormalities, while platelet transfusion is indicated for severe thrombocytopenia.

Treatment for shock might include anti-shock interventions.

Surgical Treatment

Approximately 20–40% of neonates with NEC require surgical intervention. Intestinal perforation is an absolute surgical indication. Clinical deterioration despite aggressive medical treatment, indicated by abdominal wall erythema, acidosis, and hypotension, may also necessitate surgery. Surgical options include peritoneal drainage, exploratory laparotomy, resection of necrotic or perforated intestinal segments, and anastomosis or stoma formation.

Prognosis

The long-term prognosis is favorable for neonates with stage I or stage II NEC. For neonates requiring surgical treatment, approximately 25% develop gastrointestinal long-term complications such as short bowel syndrome or intestinal stricture. Other potential complications include malabsorption, cholestasis, chronic diarrhea, and electrolyte imbalances.

Prevention

Breastfeeding is one of the most effective preventive measures against NEC and is recommended as the preferred feeding option for preterm infants. When maternal breast milk is insufficient, donor breast milk is a viable alternative. Probiotic supplementation has shown potential benefits in reducing NEC incidence in preterm infants, although questions remain about the choice of probiotic strains, dosage, timing, duration, and safety, particularly for extremely low birth weight infants. Research on the preventive use of oral arginine or glutamine-enriched formula is ongoing.