In a broad sense, malnutrition includes both undernutrition and overnutrition. This section discusses the former, which refers to growth, developmental, and functional impairments caused by insufficient intake, poor absorption, or increased consumption of protein and/or energy due to various reasons. This condition is referred to as protein-energy malnutrition (PEM). According to WHO data from 2020, malnutrition remains the most common cause of morbidity and mortality in children under the age of 5, making the prevalence of malnutrition among this age group a key indicator of national social development and progress.

Etiology

Insufficient Intake

Food Scarcity

Causes such as poverty, natural disasters, and warfare lead to food shortages, leaving children in a state of chronic hunger.

Improper Feeding Practices

A lack of parental knowledge about feeding potentially results in prolonged milk insufficiency for infants or delayed and inappropriate introduction of complementary foods (e.g., watery rice porridge/starch-heavy diets), leading to inadequate protein intake.

Dietary Habits

Unhealthy eating habits, such as picky eating or extreme food preferences, result in insufficient or unbalanced nutrient intake.

Psychological Abnormalities

Adolescents, particularly those pursuing an idealized lean figure, may engage in restrictive dieting, sometimes leading to severe conditions such as anorexia nervosa.

Structural and Functional Abnormalities of the Digestive Tract

Issues such as pylorospasm or obstruction may reduce nutrient intake.

Absorption Disorders

Long-term conditions such as chronic diarrhea and intestinal tuberculosis often result in nutrient malabsorption.

Excessive Consumption

Impact of Diseases

A variety of illnesses, including congenital heart disease, gastrointestinal malformations, malignancies, metabolic disorders, trauma, and burns, suppress appetite and reduce nutrient absorption while simultaneously increasing protein and energy expenditure in the body.

Excessive Physical Activity

Increased physical activity leads to greater energy demands.

Impaired Anabolism

Liver diseases such as cirrhosis or hepatitis lower the liver’s ability to synthesize proteins.

High-Risk Children

Groups with elevated risk include low birth weight infants, twins or multiples, and premature infants.

Pathophysiology

Metabolic Abnormalities

Protein Metabolism

Inadequate protein intake, reduced synthesis, or excessive loss creates a negative protein balance. Hypoproteinemic edema may occur when serum total protein levels drop below 40 g/L and albumin levels fall below 20 g/L.

Fat Metabolism

When energy intake is insufficient, the body mobilizes large amounts of stored fat to sustain vital activities, leading to a reduction in serum cholesterol levels. Since the liver is the primary organ for fat metabolism, nutritional deficiencies cause disruptions in very low-density lipoprotein (VLDL) synthesis by hepatocytes, impairing transport of triglycerides to extrahepatic tissues. This can result in triglyceride accumulation and fatty infiltration in the liver.

Carbohydrate Metabolism

Reduced carbohydrate intake and increased consumption result in glycogen depletion and low blood glucose levels. In mild cases, symptoms may not be evident, but severe cases can lead to hypoglycemic coma or even sudden death.

Water and Electrolyte Balance

Excessive fat breakdown increases extracellular fluid volume. Concurrently, hypoproteinemia exacerbates fluid retention and edema. Reduced ATP synthesis in PEM affects the function of the sodium-potassium ATPase at cell membranes, causing intracellular sodium retention and extracellular fluid to become hypotonic. Complications may include hypotonic dehydration, acidosis, hypokalemia, hyponatremia, hypocalcemia, and hypomagnesemia.

Body Temperature Regulation

Malnourished children often exhibit lower body temperatures. Possible contributing factors include insufficient energy intake, reduced subcutaneous fat (resulting in rapid heat loss), hypoglycemia, reduced oxygen consumption, lower heart rates, and diminished peripheral circulatory volume.

Impaired Function Across Systems

Digestive System

Gastrointestinal mucosa becomes atrophic and thinner. Reduced secretion and activity of digestive enzymes, weakened intestinal motility, and gut flora dysregulation result in impaired digestion, a tendency for diarrhea, and poor nutrient absorption.

Circulatory System

Decreased myocardial contractility leads to reduced stroke volume, lower blood pressure, and weak pulses.

Urinary System

Impaired tubular reabsorption results in increased urine output and decreased urine specific gravity.

Nervous System

Manifestations include depression, occasional irritability, apathy, slowed reactions, impaired memory, and difficulty forming conditioned reflexes.

Immune System

Both nonspecific (e.g., skin and mucosal barrier function, phagocytic activity of leukocytes, complement activity) and specific immune functions decrease significantly. Delayed skin hypersensitivity reactions, such as tuberculin tests, may turn negative. Immunoglobulin G (IgG) subclasses are frequently deficient, and T-cell subpopulations are imbalanced. Due to compromised immune responses, children with PEM are highly susceptible to infections of various kinds.

Clinical Manifestations

The clinical manifestations of malnutrition depend on factors such as age, underlying causes, and duration of the condition. Based on whether protein, energy, or both are deficient, protein-energy malnutrition (PEM) may present in three forms: marasmus, kwashiorkor, or a mixed marasmic-kwashiorkor type.

Marasmus

Marasmus arises primarily due to severe energy deficiency. The clinical presentation includes wasting. Early signs include reduced activity, diminished vitality, and failure to gain weight. As malnutrition worsens, there is progressive weight loss along with the depletion of subcutaneous fat, beginning from the abdomen, followed by the trunk, buttocks, limbs, and finally the cheeks. Ultimately, subcutaneous fat diminishes to the point of complete absence, leaving the skin dry, pale, and inelastic, often featuring wrinkles on the forehead. Muscle tone gradually decreases, muscles become flaccid, and muscular atrophy transforms the appearance into a "skin-and-bones" look, sometimes accompanied by limb contractures. Initially, height is unaffected, but growth retardation becomes noticeable as the condition progresses. In mild PEM, the mental state appears normal, while in severe cases symptoms include apathy, poor responsiveness, hypothermia, weak, thready pulses, lack of appetite, and alternating diarrhea and constipation.

Kwashiorkor

Kwashiorkor is primarily caused by severe protein deficiency and is characterized by hypoalbuminemia and edema. Edema typically begins in the lower limbs and progressively spreads upward. Due to the presence of edema, body weight may appear normal or only slightly reduced. Upon physical examination, subcutaneous fat loss is less apparent, though significant muscle wasting is evident. This form may be accompanied by exudative skin rashes or, in severe cases, infections leading to chronic ulcers.

Mixed Type (Marasmic-Kwashiorkor)

The mixed form is due to simultaneous deficiencies in protein and energy, combining characteristics of marasmus and kwashiorkor.

Malnutrition can be classified into mild, moderate, and severe based on its severity. Severe malnutrition may lead to organ damage, including renal injury or shock. Common complications of PEM include nutritional anemia, often presenting as microcytic hypochromic anemia. Deficiencies in multiple vitamins are also observed, with vitamin A deficiency being the most common. Symptoms of vitamin D deficiency are usually subtle during malnutrition but may become pronounced during recovery and rapid catch-up growth. Zinc deficiency is prevalent among most affected children. Due to impaired immune function, children with PEM frequently succumb to various infections, exacerbating their malnutrition in a vicious cycle. Additionally, spontaneous hypoglycemia may occur, presenting suddenly with pallor, confusion, bradycardia, apnea, and failure to maintain body temperature. Untreated, this condition can become life-threatening.

Laboratory Investigations

Early stages of malnutrition often lack highly specific or sensitive diagnostic markers. Hypoalbuminemia serves as a characteristic finding, though its long half-life limits its sensitivity. Prealbumin and retinol-binding protein are more responsive markers. Insulin-like growth factor-1, unaffected by liver function, is considered a reliable early diagnostic marker.

Diagnosis of malnutrition is typically based on factors such as a child’s age, feeding history, weight loss, reduction in subcutaneous fat, systemic dysfunctions, and clinical signs of nutrient deficiencies. Key diagnostic measurements for malnutrition include height (or length) and weight. Criteria for evaluating malnutrition in children under seven years old are as follows:

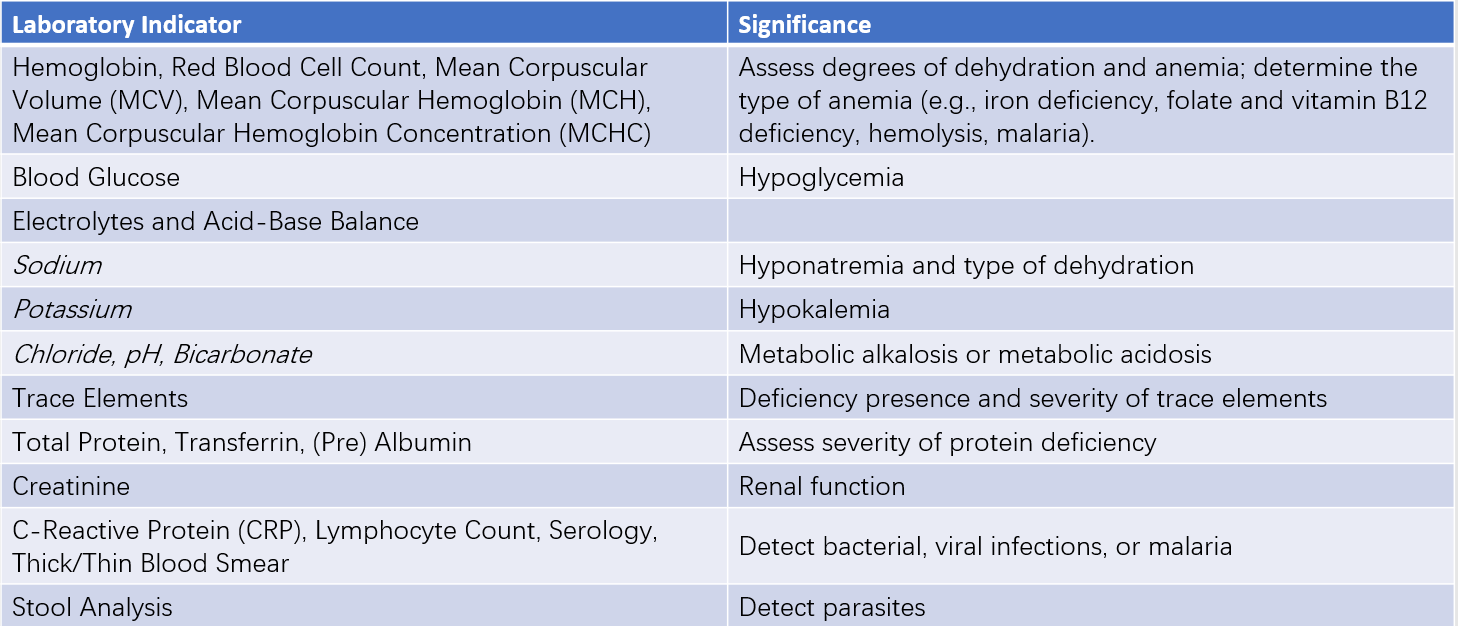

Table 1 Common laboratory indicators for protein-energy malnutrition

Underweight

Body weight that falls below X' - 2 SD of the reference population for the same age and sex is classified as underweight. A value between X' - 3 SD and X' - 2 SD corresponds to moderate underweight, while a value below X' - 3 SD indicates severe underweight. This metric primarily reflects chronic or acute malnutrition.

Stunting

Height (or length) lower than X' - 2 SD of the reference population for the same age and sex is classified as stunting. A value between X' - 3 SD and X' - 2 SD corresponds to moderate stunting, while a value below X' - 3 SD indicates severe stunting. This measure primarily reflects chronic, long-term malnutrition.

Wasting

Body weight lower than X' - 2 SD of the reference population for the same sex and height (or length) is classified as wasting. A value between X' - 3 SD and X' - 2 SD corresponds to moderate wasting, while a value below X' - 3 SD indicates severe wasting. This metric primarily reflects recent, acute malnutrition.

Clinical practice often involves combining these indicators to assess the duration and severity of malnutrition. A diagnosis of malnutrition can be made if any one of the three indicators is present, although multiple indicators often coexist. It is important to note that in cases of edema-dominated malnutrition caused by protein deficiency, weight loss may not be readily apparent.

Treatment

General Treatment

Addressing Underlying Causes and Treating the Primary Condition

Promoting breastfeeding, introducing complementary foods in a timely manner, and ensuring adequate intake of high-quality protein are emphasized. Congenital abnormalities should be corrected early, infectious diseases controlled, and chronic wasting conditions resolved.

Nutritional Support

Mild to Moderate Malnutrition

Efforts focus on a balanced diet, increased energy and protein intake, moderate supplementation of vitamins and minerals, and fostering healthy eating habits.

Severe Malnutrition

Nutritional therapy is adjusted according to the patient's gastrointestinal tolerance, with a gradual increase in energy, protein, vitamins, and trace elements. For severe cases, elemental diets or parenteral nutrition may be used. Early treatment involves correcting water and electrolyte imbalances. Energy targets start by increasing intake by 20% above the child's recent consumption or by meeting 50%-75% of the recommended intake. This is followed by a daily increase of 10%-20%, without exceeding tolerable limits. For children under three years old, energy provision should meet 100%-120% of the requirement for their standard height and weight.

Symptomatic Treatment

Dehydration, acidosis, electrolyte abnormalities, shock, renal failure, and spontaneous hypoglycemia are common fatal complications and require emergency intervention if they occur. For severe anemia, small and frequent blood transfusions may be used. Hypoproteinemia may be managed by intravenous albumin infusion. Other complications, such as eye damage caused by vitamin A deficiency and infection, also require timely treatment.

Additional Treatments

Pharmacotherapy

Various digestive enzymes (e.g., pepsin, pancreatic enzymes) are utilized to aid digestion.

Vitamins and trace elements are administered orally, with intramuscular injections or intravenous infusions as needed.

Zinc supplementation is recommended for cases of low serum zinc, as it can stimulate appetite and improve metabolism.

Enhanced Nursing Care

Parental Education

Parents are advised to gradually increase the quantity and variety of complementary foods when introducing them. Sudden or excessive adjustments should be avoided to prevent indigestion. After feeding, the oral cavity should be cleaned to prevent oral infections such as stomatitis or thrush.

Skin Care

Due to the thinning of subcutaneous fat, children are at risk for pressure sores. Soft bedding is recommended, frequent repositioning is essential, and bony prominences should be massaged multiple times daily to protect the skin and reduce the risk of infections.

Temperature Regulation

Adequate warmth should be ensured to prevent respiratory infections. Once health improves, outdoor activities can be gradually introduced to support recovery of cognitive and physical abilities.

Hygiene

Both food and utensils should be kept clean to prevent infectious diarrhea, which can further worsen malnutrition.

Prevention

Proper Feeding

Breastfeeding should be promoted, and for those with insufficient breast milk or where breastfeeding is not possible, proper guidance on mixed or formula feeding should be provided. Complementary foods should be added timely. Unhealthy eating habits, such as picky eating, food aversions, or excessive snacking, should be discouraged. Primary school children should consume a full breakfast and a lunch with sufficient energy and protein, particularly foods rich in high-quality protein.

Growth Monitoring Charts

The use of growth monitoring charts should be encouraged. Regular weight measurements should be recorded on the chart, and if weight gain is observed to slow or stop, the underlying cause should be investigated and rectified promptly.