Breastfeeding

Characteristics of Breast Milk

Breast milk is a naturally optimal food suited to meet the physiological and psychological developmental needs of infants, playing an irreplaceable role in promoting healthy growth and development. A healthy mother can provide the nutrients, energy, and fluid volume required for the normal growth of full-term infants up to six months of age. Breastfeeding not only supplies nutrition to infants but also provides substances that can be directly utilized by infants, such as lipase and secretory immunoglobulin A (SIgA), until the infant’s body is capable of synthesizing them independently.

Rich Nutritional Content

Breast milk is highly bioavailable and easily absorbed by infants. Its energy-producing nutrients are present in appropriate proportions.

Protein

The casein in breast milk is β-casein, which is low in phosphorus and forms fine curds. The albumin in breast milk consists mainly of whey protein, which promotes the formation of lactoprotein. The ratio of casein to whey protein in breast milk is 1:4, significantly different from cow's milk (4:1), making it easier to digest and absorb. The essential amino acid composition in breast milk is optimal for infants, reducing the risk of allergies in breastfed infants.

Fats

Breast milk contains abundant essential fatty acids, long-chain polyunsaturated fatty acids, lecithin, and sphingomyelin, all of which support cognitive development. The small fat globules in breast milk and the presence of lipase promote easier digestion and absorption of fats.

Carbohydrates

Breast milk is rich in lactose, which dissolves completely in the intestines, enhances absorption, and promotes intestinal motility. Lactose not only supports the growth of Bifidobacteria and Lactobacilli but also facilitates calcium absorption. Lactose forms chelates with calcium in the distal small intestine, reducing the inhibitory effect of sodium on calcium absorption, thus preventing calcium precipitation in the intestinal lumen. Additionally, when lactose is converted into lactic acid, it lowers the pH in the intestinal lumen, further promoting calcium absorption.

Minerals

The mineral concentration in breast milk is low, which aligns well with the developmental level of an infant's immature kidneys. Breast milk minerals are easily absorbed by infants. For instance, the calcium-to-phosphorus ratio in breast milk (2:1) supports good calcium absorption. Breast milk also contains a low-molecular-weight zinc-binding ligand, aiding absorption and enhancing zinc bioavailability. Although the iron content in breast milk is low (0.45 mg/L), its absorption rate is high. However, as stored iron in an infant’s body becomes depleted after four months, iron supplementation becomes necessary.

Vitamins

Breast milk contains higher levels of vitamins A, C, and E compared to cow’s milk. For mothers with a balanced diet, the vitamin content in breast milk sufficiently meets the infant's needs. However, as breast milk is low in vitamin D, it is recommended to supplement newborns with 400 IU (10µg) of vitamin D daily a few days after birth once feeding stabilizes. Breast milk also has low levels of vitamin K, and timely supplementation is advised to prevent vitamin K deficiency-related bleeding in newborns.

Biological Functions

Low Buffering Capacity

Breast milk has minimal neutralizing effects on gastric acid, facilitating digestion and absorption.

Irreplaceable Immune Components (Nutritional Passive Immunity)

The primary immunoglobulin in breast milk is SIgA, along with smaller amounts of IgM and IgG. Colostrum contains higher concentrations of SIgA. SIgA in breast milk remains stable in the stomach and exerts its effects in the intestine. It adheres to the surface of intestinal mucosal epithelial cells, blocking pathogens from attaching to the intestinal walls, inhibiting pathogen reproduction, and protecting the mucosal lining of the digestive tract. Breast milk is also rich in immunologically active cells, with colostrum containing particularly high amounts (85%–90% macrophages and 10%–15% lymphocytes). Prolactin in breast milk supports the maturation of an infant's immune system. Lactoferrin in breast milk strongly chelates iron, depriving Escherichia coli, most aerobic bacteria, and Candida of the iron needed for their growth, thereby inhibiting bacterial proliferation. Breast milk contains lysozymes that hydrolyze the acetylpolysaccharides in the cell walls of gram-positive bacteria, disrupting them and enhancing the bactericidal effects of antibodies. The levels of complement and bifidus factors in breast milk are also much higher than in cow’s milk, with bifidus factors promoting the growth of Bifidobacteria. Oligosaccharides, unique to breast milk, structurally resemble cellular adhesion molecules on intestinal epithelial cells, preventing bacterial adhesion to the gut lining while promoting the growth of Bifidobacteria and Lactobacilli.

Growth Regulatory Factors

Breast milk contains factors critical for cell proliferation and development, including taurine, hormone-like proteins (such as epidermal growth factor and nerve growth factor), as well as certain enzymes and interferons. The taurine content in breast milk is three to four times higher than that of cow’s milk. Studies indicate that breastfeeding supports the development of the infant’s immune system, enhances resistance to infections, reduces the risk of allergic diseases, and lowers the long-term risk of chronic conditions such as obesity, hypertension, coronary artery disease, and diabetes.

Other Benefits

Breastfeeding is economical, convenient, temperature-appropriate, and supports an infant's psychological well-being. For mothers, breastfeeding accelerates postpartum uterine recovery, reduces the likelihood of subsequent pregnancies, and decreases the risks of postpartum weight retention, diabetes, breast cancer, and ovarian cancer.

Variability in Breast Milk Composition

Composition During Different Stages of Lactation

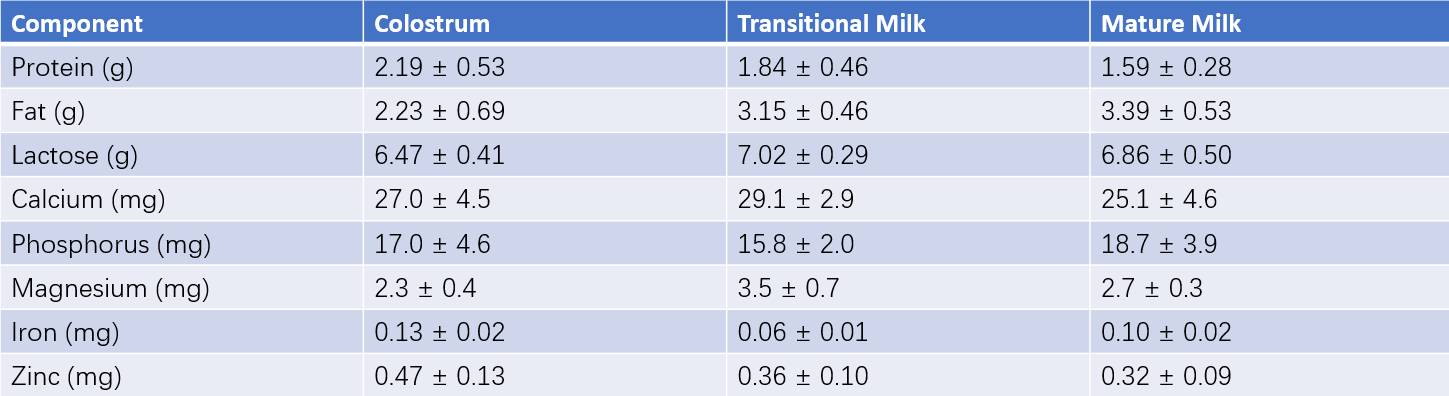

Colostrum refers to milk produced during late pregnancy and within four to five days after birth. Transitional milk is produced between days 5 and 14 post-delivery, and mature milk is produced thereafter. The levels of nutrients such as fat, water-soluble vitamins, vitamin A, and iron in breast milk are influenced by the maternal diet, while levels of vitamins D, E, and K are less affected as these vitamins do not easily transfer from blood to milk.

Colostrum is small in volume, yellowish in color, alkaline in nature, and has a specific gravity of 1.040–1.060 (compared to 1.030 in mature milk), with a daily volume of about 15–45 ml. It is low in fat but higher in protein, primarily immunoglobulins. Colostrum is particularly rich in vitamin A, taurine, and minerals, and contains colostrum corpuscles (macrophages filled with fat globules and other immune-active cells), which play a crucial role in growth, development, and infection resistance in newborns. Over time, the protein and mineral content in breast milk decreases gradually, while lactose levels remain relatively stable across all stages of lactation.

Table 1 Composition of breast milk at different stages (Nutrient content per 100g of milk)

Changes in Breast Milk Composition During a Feeding Session

The composition of breast milk varies during each feeding session. If a feeding session is divided into three parts, the first portion of milk contains lower fat but relatively higher protein, the second portion sees a gradual increase in fat content and a decline in protein levels, and the final portion contains the highest fat concentration.

Milk Volume

The daily milk production of a lactating mother gradually increases over time, and an average volume of 700–1,000 ml can be reached with mature milk. Generally, after six months postpartum, both the quantity and nutritional components of breast milk show a gradual decline. Milk adequacy is assessed comprehensively based on infant weight gain, urine output, and sleep quality, rather than solely on production volume.

Establishing Effective Breastfeeding Practices

Successful breastfeeding involves active participation and satisfaction for both mother and infant. Three conditions are essential for effective breastfeeding:

- The mother must be able to produce an adequate milk supply.

- A functional let-down reflex must occur during feeding.

- The infant must be capable of vigorous and effective sucking. Exclusive breastfeeding is recommended for the first six months after birth.

Preparations During Pregnancy

Most healthy pregnant women have the physical capacity to breastfeed; however, successful breastfeeding also requires mental preparation and proactive measures. Pregnant mothers should maintain proper nutrition and achieve appropriate weight gain (12–14 kg during pregnancy) to store sufficient fat reserves necessary for the energy demands of lactation.

Nipple Care

In the later stages of pregnancy, the mother should clean her nipples daily with water (avoiding soap or alcohol-based products). For inverted nipples, applying pressure and gentle pulling from different angles using both thumbs on either side of the nipple can help correct the condition, which can also be improved with the assistance of devices. After each breastfeeding session, expressing a small amount of breast milk and applying it onto the nipples can take advantage of the milk’s rich protein and antibacterial properties, which help protect the skin and prevent nipple cracking.

Early Initiation of Breastfeeding

Early initiation of breastfeeding is essential for successful lactation. Milk production involves a cooperative process between mother and infant. The newborn's sucking plays a role in establishing and reinforcing the reflexive connections between sucking, prolactin secretion, and milk production, providing the foundation for effective breastfeeding. Beginning breastfeeding within 15 minutes to 2 hours postpartum supports early establishment of lactation, reduces the risk of neonatal physiological jaundice, weight loss, and hypoglycemia.

Responsive Feeding

Responsive feeding is an approach that aligns with the infant’s natural feeding cues and patterns. The duration and frequency of feedings are determined by the infant’s hunger and nutritional needs. It includes on-demand feeding during the early postnatal period and a more routine feeding schedule as the infant grows. On-demand feeding is particularly suited to infants less than three months of age, where feedings are dictated by hunger without enforcing rigid intervals or durations. As the infant’s gastrointestinal system matures and growth progresses, breastfeeding naturally transitions from on-demand feeding to a more structured schedule. Responsive feeding ensures adequate milk intake while facilitating the establishment of feeding, activity, and sleep rhythms.

Enhancing Milk Production

Applying heat to the breasts before feeding promotes blood circulation in the breast tissue. After two to three minutes, gentle tapping or massaging from the outer edges toward the areola stimulates the sensory nerves in the breasts and enhances milk secretion. Alternating between both breasts ensures balanced breastfeeding. If one breast produces sufficient milk for the infant’s needs, alternating breasts between feeds can be practiced, with milk from the other breast expressed using a pump to maintain milk production. Emptying the breast during each feeding session supports continued milk secretion. Milk production is influenced by various hormones regulated by the hypothalamus, which is closely tied to emotional well-being. Maintaining a positive emotional state and ensuring adequate rest and sleep promote milk production.

Correct Feeding Techniques

Adopting the correct breastfeeding posture supports oral motor function in infants and facilitates effective sucking. A properly chosen breastfeeding position ensures comfort and relaxation for both the mother and the infant. Correct feeding practices also involve facilitating the infant’s readiness for feeding (awake and exhibiting signs of hunger). Before feeding, the infant can nudge the breast with their nose or lick the nipple with their tongue to stimulate the mother’s let-down reflex. Factors such as the infant’s scent and physical contact during breastfeeding further enhance the reflex.

Situations Unsuitable for Breastfeeding

Certain conditions may make breastfeeding or conventional breastfeeding methods inappropriate, requiring individualized feeding plans:

- Infants diagnosed with specific congenital or hereditary metabolic disorders.

- Mothers with infectious diseases or mental illnesses. In cases of acute infectious diseases, expressed breast milk can be sterilized and provided to the infant. Hepatitis B virus carriers are not automatically prohibited from breastfeeding.

- Mothers who use certain harmful substances or medications that may have toxic side effects on the infant.

Partial Breastfeeding

Partial breastfeeding involves feeding the baby with both breast milk and formula milk or animal milk. Two methods can be used:

Supplementation Method

When breastfeeding infants under four months do not show satisfactory weight gain, it may indicate insufficient breast milk. With supplementation, the frequency of breastfeeding remains unchanged, and for each session, both breasts are emptied before supplementing with formula milk or animal milk to cover the shortfall. This method is suitable for infants aged zero to six months. The volume of supplementation depends on the infant's appetite and the amount of breast milk available, following a "supplement what is missing" approach. This method also supports stimulation of breast milk secretion.

Substitution Method

The substitution method replaces one breastfeeding session with formula milk or animal milk. This approach is often used when preparing to wean a breastfed infant. Gradually reducing the amount of breast milk provided during certain feeding sessions and increasing the quantity of formula milk or animal milk facilitates a smooth transition until breast milk is completely replaced.

In recent years, many countries have been developing and expanding human milk banks. When breastfeeding is deemed unsuitable or insufficient, access to donor breast milk from a human milk bank can be arranged if conditions allow.

Artificial Feeding

When breastfeeding is not possible due to various reasons, formula milk or other types of animal milk, such as cow's milk, goat's milk, or horse milk, can be used for infant feeding, which is referred to as artificial feeding. Formula milk products are primarily derived from cow's milk and modified to bring their nutritional composition as close as possible to that of breast milk, while fortifying essential nutrients such as iron and vitamins. Formula milk is designed to suit an infant's digestive capacity and renal function and to address the relative inadequacies of certain key nutrients in breast milk. When breastfeeding is not feasible, formula milk should be the preferred source of nutrition. Infants with special metabolic disorders or illnesses may require formula foods formulated for specific medical purposes.

Correct Feeding Techniques

As with breastfeeding, artificial feeding requires proper feeding techniques, including appropriate feeding posture and stimulating the infant’s readiness to feed. Attention should be given to the temperature of the milk, positioning of the bottle, and selection of suitable nipples and bottles. During feeding, maximizing eye contact between the infant and the caregiver is important.

Estimating Intake

Information such as the infant’s weight, Recommended Nutrient Intakes (RNI), and formula specifications is necessary to estimate formula milk intake. Formula milk should be prepared according to the manufacturer’s instructions. Typically, commercially available infant formula provides approximately 500 kcal per 100g. For infants under six months, daily energy requirements are approximately 90 kcal/kg, necessitating about 18g/kg or 135ml/kg of formula milk. However, feeding needs vary from infant to infant, and adjustments should be based on individual requirements.

Transition to Infant Foods

As infants grow and mature, they undergo a transitional phase during which their diet shifts from exclusively milk-based to solid foods. This process introduces infants to various food flavors, fosters interest in different types of food, and progressively transitions their diet from a milk-based foundation to one centered on solid foods.

Transitional Foods

Transitional foods, also known as complementary foods, include both semi-solid and solid foods. Semi-solid foods, such as rice cereal, root vegetables, and fruits, offer advantages like ease of absorption, low allergenicity, meeting growth needs, and training taste preferences. Solid foods include fish, eggs, meat, and soy products, which provide additional variety, harder textures, and higher nutritional density. These foods also facilitate gripping and chewing, promoting essential motor skill development.

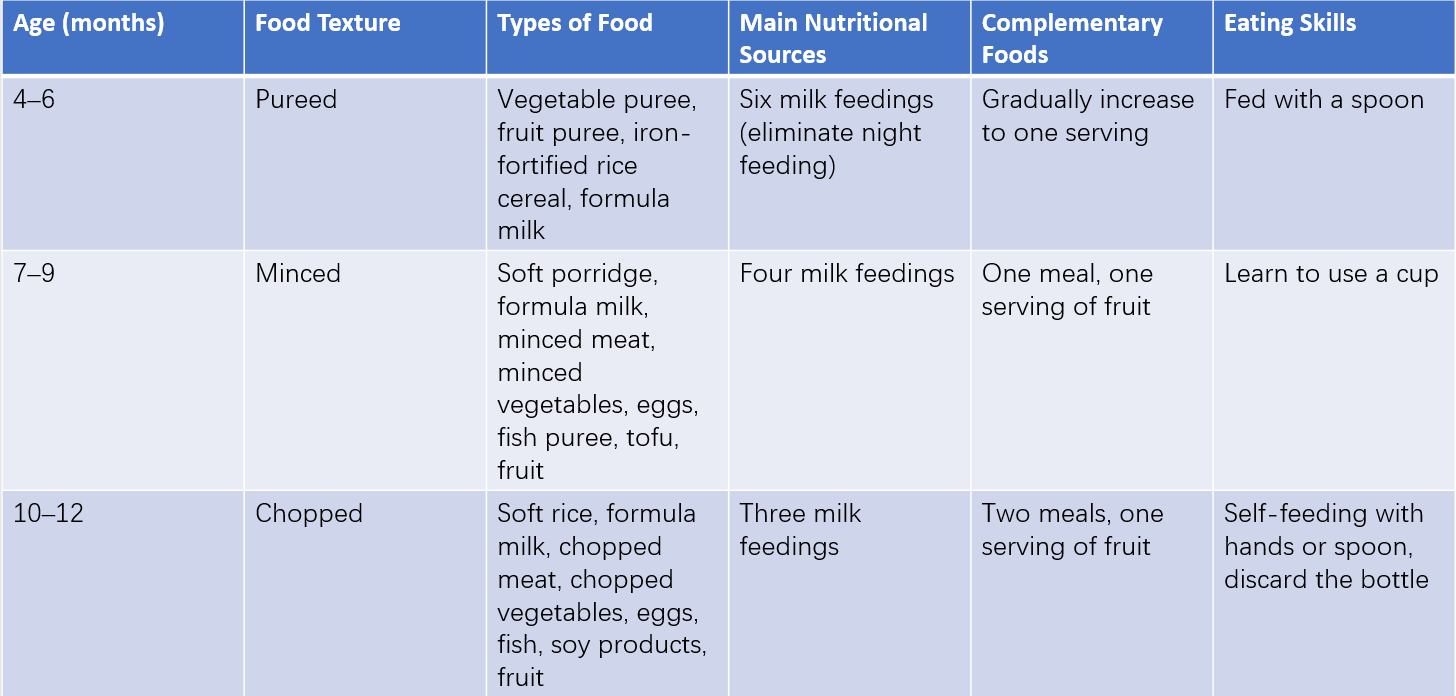

Table 2 Introduction of complementary foods during the weaning phase

Food Transition Process

The transition process is determined by the infant’s physical growth, neurological development, feeding skills, and social abilities. Complementary foods can generally be introduced when infants weigh between 6.5–7 kg, show stable posture control, can sit while supported, and can eat using a spoon. It is recommended to begin complementary feeding at six months. At this point, the nutritional value of breast milk begins to decline, no longer fully meeting an infant’s growth needs, while the digestive tract matures sufficiently to process other foods.

Key principles for introducing complementary foods include:

- From Small to Large Quantities: After six months, small amounts of iron-fortified rice cereal can be offered immediately after breastfeeding. Feeding with a spoon begins in small quantities, and by 6–7 months, one breastfeeding session can be replaced.

- From Single to Multiple Types: Introducing foods individually, such as vegetable puree, involves offering the same food one to two times daily, continuing for three to four days until the infant becomes accustomed before introducing another food. This approach supports taste development and helps identify potential food allergies.

- From Smooth to Textured: Transitioning from pureed textures to finely minced foods encourages chewing and increases the energy density of the diet.

- From Soft to Hard: As the infant grows, harder textures can be introduced, promoting tooth eruption and the development of chewing abilities.

- Feeding Skills Development: Encouraging active participation in feeding, such as allowing infants aged seven to nine months to handle food and training older infants to use a spoon, increases interest in eating and supports coordination between hand and eye movement while fostering independence. Passive or forceful feeding methods that evoke feelings of fear or food aversion in infants should be avoided.