The process of obtaining medical history, conducting physical examinations, and documenting findings in pediatrics has its own unique characteristics in terms of content, procedures, methods, and analytical judgment. These features differentiate it from the approach used for adults. Mastery of these specialized methods and techniques forms the foundation of pediatric clinical diagnosis and treatment.

Advancements in medicine and the overall improvement in diagnostic and treatment standards have heightened expectations for physicians to apply systematic medical knowledge, basic clinical skills, and correct clinical reasoning. Proficient and standardized collection of medical history, along with thorough physical examinations and proper medical record documentation, is crucial for developing comprehensive clinical competence and establishing accurate disease diagnoses. While developments in clinical laboratories and diagnostic equipment provide more precise tools for identifying diseases, accurate history-taking and physical examinations remain fundamental to sound medical diagnoses. Medical records documented during this process serve as the most critical evidence in medical practice.

It is important to note that for emergencies or critically ill patients, initial emphasis should be given to brief assessments and lifesaving measures. Comprehensive history-taking and detailed physical examinations can be conducted once the patient's condition has stabilized.

Medical History Collection and Documentation

The collection of medical history needs to be accurate. Key elements include listening attentively and asking focused questions, while identifying diagnostic clues from details provided by parents or guardians. A kind and approachable demeanor, along with clear and simple language, facilitates communication and builds trust with caregivers. Parents should sense that the healthcare provider cares about the child’s well-being. Respecting the privacy of both the child and the caregivers, along with maintaining confidentiality, is essential. Preconceived notions should be avoided, and leading or suggestive language that might influence subjective responses from caregivers should not be used, as this could complicate the diagnostic process. The following are the key components of medical history-taking:

General Information

This involves accurately recording the child’s name, gender, and age (actual age should be detailed: days for newborns, months for infants, and years and months for children above one year of age); race; the names, occupations, ages, and educational levels of the parents or caregivers; their home address and/or other contact information (e.g., phone number). The relationship of the narrator to the child, as well as the reliability of the history provided, should also be documented.

Chief Complaint

This refers to a concise summary of the main symptom(s) or sign(s) and their duration based on the caregiver’s description. For example: "Intermittent abdominal pain for 3 days" or "Persistent fever for 5 days."

Present Illness

This is the main section of the medical record, providing a detailed account of the current illness, including the main symptoms, progression of the condition, and prior diagnostic and treatment processes. The following points are particularly emphasized during the collection:

Main Symptoms

These should be inquired about thoroughly, including their characteristics. For example, questions regarding a cough should cover aspects such as persistence or intermittence; severity (mild, severe); whether it is single or continuous; its paroxysmal nature, presence of crowing sounds, whether sputum is produced and its characteristics; timing during the day when the cough is more pronounced, accompanying symptoms, and potential triggers.

Differentiating Symptoms

Symptoms that provide differential diagnostic value, including negative findings, should also be inquired about and documented.

General Conditions Post-Onset

Information about the child’s general condition following the onset of the illness, such as mental state, feeding or appetite, bowel and urinary habits, sleep patterns, and symptoms related to other systems, should be included.

Previous Examinations and Results

Any past diagnostic tests performed and their results should be noted.

Previous Treatments

Details about medications used, including the names, doses, administration methods, timing, efficacy, and any adverse reactions, should be recorded if applicable.

Personal History

This section includes a detailed account of the child’s birth history, feeding history, and developmental milestones. The focus and level of detail vary based on the child’s age and the nature of the illness.

Birth History

This includes details about the mother’s condition during pregnancy, whether it was the first pregnancy and delivery, gestational age at delivery (term, preterm, or post-term), mode of delivery, birth weight, any asphyxia or birth injuries, use of oxygen, and whether invasive or non-invasive respiratory support was required. For neonates and infants suspected of central nervous system underdevelopment or developmental delays, an in-depth understanding of perinatal conditions becomes even more critical.

Feeding History

This includes whether the child was breastfed, formula-fed, or given mixed feeding, the type of milk or milk substitute used, how it was prepared, the frequency and quantity of feedings, the timing of weaning, when complementary foods were introduced, the types and amounts of such foods, and the child's eating and bowel habits. For older children, information about picky eating, food preferences, or snacking habits is also relevant. Understanding feeding history is particularly important for children with nutritional or digestive system disorders.

Growth and Development History

Common indicators of growth include weight, height, and patterns of increase over time. Further details include the closure time of the anterior fontanel, timing of deciduous teeth eruption, and developmental milestones such as when the child began lifting their head, smiling, sitting without support, standing, walking, and saying "mama" or "dada" intentionally. For school-aged children, their performance at school and behavior also warrant attention.

Past Medical History

This includes previous illnesses and vaccination history.

Past Illnesses

A detailed inquiry should cover previous diseases, the timing of the illnesses, and treatment outcomes. This includes neonatal illnesses and hospitalization, recurrent respiratory infections, and any history of drug or food allergies, with detailed documentation. For infectious diseases, such as a child with a history of measles who currently presents with fever and rash, consideration of other febrile rash illnesses would be emphasized during comprehensive analysis. For older children or complex cases with prolonged courses, a systemic review of all organ systems may provide valuable insights for diagnosis and treatment.

Vaccination History

Information about routine immunization schedules should be obtained, including the types of vaccines received, timing, number of doses, and whether there were any reactions. Vaccinations outside the routine immunization schedule should also be documented.

Family History

This includes the presence of hereditary, allergic, or acute and chronic infectious diseases among family members. If such conditions exist, the nature of the contact with the affected child should be assessed in detail. Additional information encompasses whether the parents have a consanguineous marriage, the mother’s pregnancy and delivery details, and the health status of siblings (for deceased siblings, the cause and age of death should be clarified). When necessary, inquiries about the health status of family members and relatives, the family’s economic situation, living environment, the parents’ degree of care for the child, and their understanding of the child’s illness may also be made. Documentation of such information requires parental consent.

History of Contact with Infectious Diseases

For cases suspected to involve infectious diseases, the history of contact with such conditions must be explored in detail. This includes the child’s relationship to suspected or confirmed cases, the treatment and outcomes of the infectious individual, as well as the nature and duration of the child’s contact with that person. Understanding the parent's knowledge and awareness of infectious diseases can also contribute to diagnosis.

Physical Examination

To ensure the accuracy of physical examination findings, creating a natural and relaxed atmosphere during history taking facilitates the child’s cooperation. The physician’s demeanor is critical in determining the level of cooperation from both the child and their parents.

Considerations for the Physical Examination

Building rapport with the child begins during history taking. Smiling, addressing the child by their name or a nickname, offering verbal encouragement, or gently stroking can help ease anxiety. Using a stethoscope or toys to engage the child may also reduce fear and build trust. During this process, observations of the child’s mental state, responsiveness to external stimuli, and cognitive abilities should be made.

To increase the child’s sense of security, it is beneficial to conduct the examination with parents present. For example, infants and toddlers may sit or lie in a parent’s arms during chest auscultation, with examination conducted in positions that align with the child’s comfort.

The sequence of examination is flexible and should align with the child’s current condition. For infants and toddlers, whose attention spans are brief, the following key points are noteworthy: quiet tasks such as auscultation of the heart and lungs, measuring heart rate and respiratory rate, or abdominal palpation—being subject to crying—are best performed early in the examination. Readily observable areas, such as the limbs, torso, skeleton, and superficial lymph nodes, can be examined at any point. Areas potentially distressing to the child, such as the oral cavity and throat, or painful regions, are better left for last.

The examiner’s demeanor should be kindly, with gentle movements. Hands and stethoscope components should be warmed during colder seasons. The examination process requires thoroughness, yet care must be taken to keep the child warm and avoid unnecessarily exposing their body to reduce the risk of chills. For older children, sensitivity to their feelings of shyness and their sense of self-respect is crucial, and their need for privacy must be respected.

For emergency or critically ill cases, priority should be given to assessing vital signs or focusing on areas most relevant to the immediate condition. Comprehensive examinations are best conducted once the situation has stabilized, although concurrent assessment during resuscitative efforts may sometimes be appropriate.

Since children—especially neonates and premature infants—have weaker immune barriers, precautions to prevent cross-infection are particularly important. These include frequent handwashing, regular disinfection of the examiner’s clothing and equipment, including stethoscopes.

Examination Methods

General Conditions

During history-taking, close observation of the child’s nutritional status, development, consciousness, facial expressions, reactions to their surroundings, skin color, posture, gait, and language abilities provides valuable and realistic information for assessing their general condition.

Basic Measurements

This includes body temperature, respiratory rate, heart rate, blood pressure, height (or length), weight, head circumference, and chest circumference.

Body Temperature

Depending on the child’s age and condition, different methods for measuring temperature may be selected:

Axillary Measurement

This is the most commonly used method due to its safety and convenience, though it requires a longer measurement time. The disinfected thermometer tip is placed in the child's armpit, with the upper arm pressed tightly against the body for at least 5 minutes. Normal temperature is 36–37°C.

Oral Measurement

This method is accurate and convenient, with a measurement duration of 3 minutes. A normal temperature is 37°C. This method is used in children over 6 years of age who are conscious and cooperative.

Rectal Measurement

This method provides a short measurement time and high accuracy. The child is placed in the lateral position with their legs flexed, and the lubricated thermometer is gently inserted 3–4 cm into the rectum for 3–5 minutes. Normal temperature is 36.5–37.5°C. This method is suitable for children under 1 year of age, uncooperative children, or those who are comatose or in shock.

Tympanic (Ear) Measurement

This method is both accurate and quick, avoids cross-infection, and minimizes irritation to the child. It has become more commonly used in both clinical and home settings.

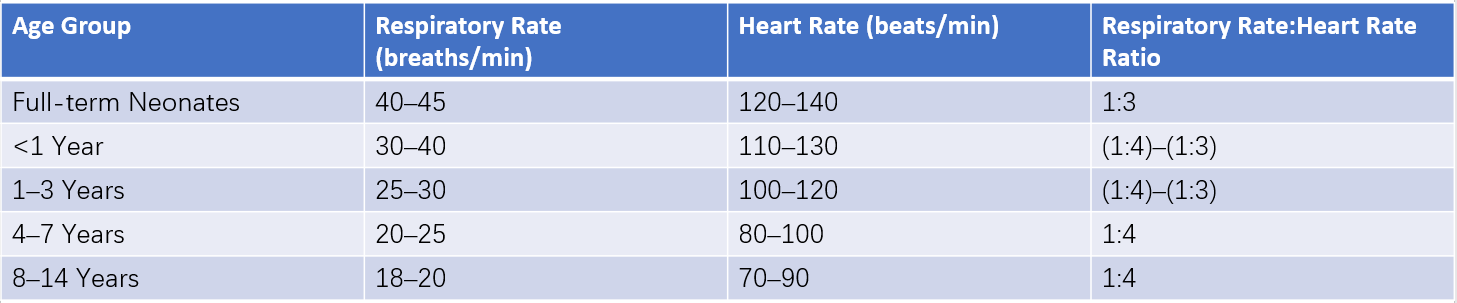

Respiratory Rate and Heart Rate (Pulse Rate)

These measurements are ideally taken when the child is in a calm state. Respiratory rate can be observed through auscultation or abdominal movements, with attention to rhythm and depth. Pulse rate is typically assessed in older children by palpating a superficial artery such as the radial artery. In infants and young children, the femoral artery or auscultation of the heart may be used. When palpating the pulse to evaluate heart rate, characteristics such as rate, rhythm, strength, and tension are considered.

Table 1 Respiratory rate and heart rate in children of different ages

Blood Pressure

Blood pressure measurement requires an appropriately sized cuff based on the child’s age. The cuff’s width should typically cover 1/2 to 2/3 of the upper arm’s length. Using an incorrect cuff size can affect accuracy; a cuff that is too wide underestimates blood pressure, while one that is too narrow overestimates it. Neonatal blood pressure is often measured using an oscillometric electronic blood pressure monitor. Blood pressure values are generally lower in younger children. For children aged 2 and older, normal systolic blood pressure (mmHg) can be estimated using the formula: 80 + (age × 2). Diastolic blood pressure is approximately two-thirds of the systolic pressure.

Skin and Subcutaneous Tissue

Observation under natural light provides the most accurate findings. The skin of various body regions is examined for color, noting pallor, jaundice, cyanosis, flushing, rashes, petechiae, desquamation, and pigmentation. Hair is assessed for abnormalities. Skin elasticity, subcutaneous tissue, and fat thickness are evaluated by touch, along with the presence and characteristics of edema.

Lymph Nodes

Lymph nodes are examined for size, number, mobility, texture, adherence, and tenderness. Special attention is given to the cervical, post-auricular, occipital, and inguinal regions. Normally, small, soft, and mobile lymph nodes the size of a soybean can be palpable in these areas without tenderness.

Head

Skull

Observations focus on size, shape, and, when necessary, head circumference measurements. The size and tension of the anterior fontanel, as well as indications of depression or bulging, are examined. Cranial sutures are assessed for separation, and abnormalities such as occipital alopecia, cranial softening, hematomas, or skull defects are noted in infants.

Face

The presence of any distinctive facial features, intercanthal width, nasal bridge height, and the position and shape of the ears are evaluated.

Eyes, Ears, and Nose

Eyelids are checked for edema, drooping, or exophthalmos, while the conjunctiva is examined for redness and the presence of discharge. Corneal transparency, pupil size and shape, and light reflex responses are assessed. External auditory canals are checked for discharge, redness, swelling, and pain on manipulation. If otitis media is suspected, tympanic membrane inspection using an otoscope is performed. Nasal structure is observed for flaring of the nostrils, nasal discharge, and patency.

Oral Cavity

The lips are examined for color changes such as pallor or cyanosis, dryness, angular stomatitis, or herpes lesions. The buccal mucosa, gums, and hard palate are assessed for redness, ulcers, plaques, or thrush. Inspection also considers the number of teeth, caries, the condition of Stensen's duct openings, and the appearance of the tongue, including color, coating, or signs of "strawberry tongue." Examination of the pharynx is performed last during the physical examination. The examiner stabilizes the child’s head and holds a tongue depressor in one hand. When the child opens their mouth, the tongue depressor is used to press the base of the tongue, briefly exposing the pharynx for inspection. Observations include the presence of swollen tonsils, redness, secretions, pus spots, membranes, ulcers, hyperemia, follicular hyperplasia, or retropharyngeal abscesses.

Neck

The neck is checked for flexibility, congenital abnormalities such as torticollis, short neck, or web neck, and cervical spine mobility. The thyroid gland is evaluated for enlargement, while tracheal position and jugular vein distention are assessed. Observations also include muscular tone, noting any increases or decreases.

Chest

Thorax

Observations include identifying abnormalities such as pectus carinatum, pectus excavatum, rachitic rosary, Harrison’s groove, or flaring of the costal margins as signs of rickets. Attention is given to the symmetry of both sides of the chest, precordial bulging, presence of a barrel chest, fullness or retraction of the intercostal spaces, and whether the intercostal spaces appear widened or narrowed.

Lungs

Inspection considers respiratory rate, rhythm, and any signs of abnormalities, such as dyspnea or changes in breathing depth. Inspiratory dyspnea may result in suprasternal, supraclavicular, intercostal, or subxiphoid retractions during inhalation. Expiratory dyspnea may be indicated by prolonged expiration. Palpation, particularly in younger children, can often be performed during crying or speaking. Due to the thin chest walls in children, percussion resonance is less pronounced than in adults. Hence, lighter percussion or direct percussion using two fingers on the chest may be more effective. During auscultation, breath sounds in children are generally louder than in adults and exhibit a bronchoalveolar character. Auscultation of the axillae, interscapular region, and subscapular region should focus on potential abnormalities, as these areas are more likely to reveal fine crackles in cases of pneumonia. In crying children, fine crackles associated with pneumonia are often detected during deep inspiration right after crying.

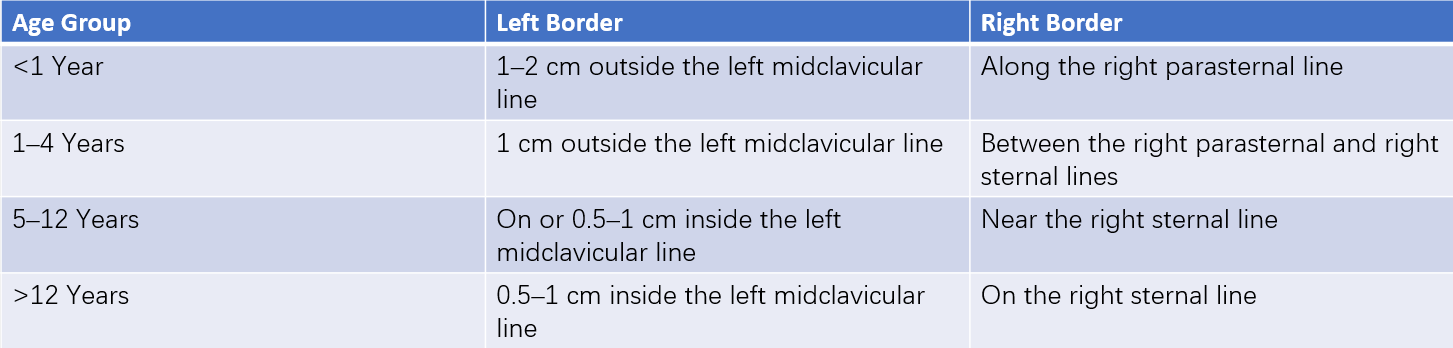

Heart

Inspection focuses on precordial bulging, the strength and area of the apical impulse, which in normal children typically spans a range of 2–3 cm2 (in obese children, the apical impulse may not be easily visible). Palpation assesses the location of the apical impulse and checks for the presence of a thrill. Percussion allows estimation of the heart’s size, shape, and position within the thoracic cavity. Gentle percussion assists in distinguishing clearer dullness boundaries. In children below three years of age, percussion is typically limited to the left and right heart borders. For the left border, percussion begins from the left of the apical impulse point and proceeds medially, noting changes to dullness, recorded as a certain number of centimeters inside or outside the left midclavicular line. For the right border, percussion starts from the liver dullness border superiorly and moves medially, recording changes to dullness as a certain number of centimeters from the right sternal line (right border of the sternum). A reference table for heart borders across different ages is provided. Cardiac auscultation in children should be conducted in a quiet environment using a stethoscope with a small chest piece. In infants, the loudness of the first (S1) and second heart sounds (S2) is nearly equal. With age, S1 becomes louder than S2 at the apex, while S2 becomes louder than S1 at the base. In children, the second pulmonary sound (P2) is louder than the second aortic sound (A2), and inspiratory splitting of S2 may occur. In preschool and school-aged children, physiological systolic murmurs or sinus arrhythmia may be heard over the pulmonary valve or apical region.

Table 2 Heart borders in children of different ages

Abdomen

During inspection, intestinal patterns or peristaltic waves are often visible in neonates or thin children. Neonates should be examined for umbilical abnormalities such as discharge, bleeding, inflammation, or hernia size. Palpation requires cooperation from the child, with warm and gentle hands. In cases of persistent crying, abdominal palpation can be performed during deep inspiration. Assessment of tenderness should rely more on the child’s facial expressions rather than verbal responses. In normal infants and young children, the liver is palpable 1–2 cm below the costal margin, soft and non-tender; by age 6–7 years, it is usually non-palpable below the costal margin. Occasionally, the spleen edge can be palpated in infants. Percussion, whether direct or indirect, follows the same approach as in adults. During auscultation, hyperactive bowel sounds may occasionally be heard. In cases where vascular murmurs are present, their nature, intensity, and location are noted.

Spine and Limbs

Observations include abnormalities, joint mobility, redness, or swelling, as well as the proportionality between the trunk and limbs. Signs of rickets such as bowlegs (O-shaped legs), knock-knees (X-shaped legs), wrist or ankle deformities, and scoliosis are noted. Examination also assesses the presence of finger or toe abnormalities, such as clubbing, polydactyly, or syndactyly.

Perineum, Anus, and External Genitalia

Examinations check for congenital abnormalities such as imperforate anus, hypospadias, or ambiguous genitalia, as well as anal fissures. In females, observations include vaginal secretions or structural abnormalities. In males, cryptorchidism, excessive or tight foreskin, hydrocele, or inguinal hernia are considered.

Nervous System

Appropriate examinations are selected based on the specific condition, disease progression, and the child’s age.

General Examination

Observations include consciousness, mental state, facial expressions, response sensitivity, motor and language skills, and the presence of abnormal behaviors.

Neurological Reflexes

Neonatal reflexes, such as the sucking reflex, Moro reflex, or grasp reflex, are assessed. Certain reflexes are age-specific. For example, the cremasteric and abdominal reflexes may be weak or absent in neonates and infants, whereas hyperactive Achilles reflexes and ankle clonus may be present. In children under two years of age, the Babinski sign may be positive; however, unilateral positivity accompanied by contralateral negativity has clinical significance.

Meningeal Irritation Signs

Assessments of neck stiffness, Kernig’s sign, and Brudzinski’s sign follow adult methodologies; repeated evaluations may be necessary in uncooperative children for accurate judgment. In normal young infants, Kernig’s and Brudzinski’s signs may also be positive during the first few months of life due to fetal dominance of flexor muscles. Interpretation of these signs requires consideration of the child’s clinical condition and age-specific characteristics.

Documentation of Physical Examinations

Although the sequence of physical examination may vary during assessment, findings should be documented in the order outlined above. Both positive and significant negative findings are included in the records.