During childhood growth, normal neuropsychological development is of equal importance to physical growth. Neuropsychological development encompasses areas such as perception, motor skills, language, emotion, thinking, judgment, and personality, all of which rely on the development and maturation of the nervous system. Similar to physical growth, abnormalities in neuropsychological development can be early indicators of systemic diseases. Understanding the patterns of psychological development in children is therefore helpful for early disease diagnosis.

Development of the Nervous System

During the fetal period, the nervous system develops earlier than other systems. By the time of birth, the brain weight of a newborn reaches about 25% of that of an adult, and the number of nerve cells is already close to that of an adult. However, their dendrites and axons are few and short. After birth, the increase in brain weight is primarily attributable to the enlargement of nerve cell volume, the growth and elongation of dendrites, and the formation and development of myelin sheaths. The formation and development of myelin sheaths are typically completed by the age of 4. Before this process, particularly during infancy, the conduction of nerve impulses in response to various stimuli is slow and easily generalized, making it difficult to form focal excitations. Infants also tire easily and often enter a sleep state.

The spinal cord grows with age. During the fetal period, the lower end of the spinal cord is at the lower edge of the second lumbar vertebra. By age 4, it shifts upward to the first lumbar vertebra. This anatomical change is important when performing lumbar punctures. The grasp reflex typically disappears by 3 months of age. Tendon reflexes in infants are relatively weak, and abdominal wall reflexes and cremasteric reflexes are also difficult to elicit, stabilizing only after 1 year of age. Before 3–4 months of age, babies often exhibit high muscle tone. A positive Kernig sign may be observed during this period, and a positive Babinski reflex in children under 2 years old can also be considered a physiological phenomenon.

Development of Sensory Perception

Visual Perception Development

Newborns exhibit some degree of visual response, with pupils reacting to light. In a calm and alert state, they can briefly fixate on objects but can only see items within a distance of 15–20 cm. By the second month, coordinated gaze develops, and head-eye coordination begins to emerge. At 3–4 months, infants enjoy looking at their own hands, with improved head-eye coordination. By 6–7 months, the eyes can follow objects moving vertically, and by 8–9 months, depth perception begins to develop, allowing recognition of small objects. At 18 months, children can distinguish different shapes. By 2 years of age, they can differentiate between vertical and horizontal lines. By 5 years, color vision is well-developed, and by 6 years, depth perception is fully established.

Auditory Perception Development

At birth, the tympanic cavity lacks air, resulting in poor hearing. Within 3–7 days after birth, hearing improves significantly. At 3–4 months, infants can turn their head toward a sound source and smile upon hearing pleasant sounds. By 6 months, they can distinguish their parents' voices. At 7–9 months, they begin to understand the tone of voices. By 10–12 months, they can recognize their name. Between 1–2 years, they can follow verbal instructions, and auditory development is typically complete by 4 years of age. Auditory perception development is directly linked to language development. Hearing impairments not diagnosed and addressed within the critical language development window (the first 6 months) may lead to speech delays resulting from hearing loss.

Development of Taste and Smell

Taste

At birth, taste perception is already well-developed. By 4–5 months, infants become highly sensitive to even slight changes in food flavor. This period is considered critical for taste development, and complementary foods should be introduced during this time.

Smell

At birth, the olfactory center and sensory nerve endings are largely developed. Infants can distinguish between pleasant and unpleasant smells by 3–4 months and begin to respond to aromatic scents by 7–8 months.

Development of Skin Sensitivity

Skin sensitivity encompasses touch, pain, temperature, and deep sensations. Touch provides the basis for certain reflexes. Newborns exhibit high sensitivity to touch around their eyes, mouth, palms, and soles, whereas touch in areas such as the forearms, thighs, and trunk is less developed. Pain perception is present at birth but remains less sensitive, improving gradually from the second month onward. Temperature sensitivity is well-developed at birth. Deep sensation refers to proprioceptive feedback from muscles, tendons, joints, and ligaments.

Motor Development

Motor development is categorized into gross motor skills (including balance) and fine motor skills.

Balance and Gross Motor Development

Head Control

Newborns can lift their head for 1–2 seconds in the prone position. By 2 months, they can lift their head 45°–90°. At 3 months, head control is steadier, and by 4 months, it becomes fully stable.

Rolling Over

At 4 months, infants can roll from a supine to a side-lying position. Between 4–7 months, deliberate upper and lower limb movements can lead to segmented rolling from supine to prone and back again.

Sitting

By 6 months, infants can sit independently by propping themselves up with their hands. At 8–9 months, they can sit steadily and turn their body to either side.

Crawling

By 8–9 months, infants can crawl forward using both arms.

Standing, Walking, and Jumping

Between 8–9 months, infants can briefly stand while holding onto a support. By 10–14 months, they can stand independently and begin walking with support. At 1.5 years, walking becomes steadier. Between 18–24 months, toddlers can run and jump with both feet. By 3 years, they can jump forward with feet together and hop on one foot.

Fine Motor Development

After the disappearance of the grasp reflex at 3–4 months, infants gain better control of their fingers. By 6–7 months, they begin exploratory movements such as transferring objects between hands, pinching, and tapping. By 9–10 months, they can use their thumb and index finger to pick up small objects and enjoy activities like tearing paper. By 12–15 months, they can use a spoon and scribble. By 18 months, they can stack 2–3 blocks. By 2 years, they can stack 6–7 blocks and turn pages in a book.

Language Development

Language development is closely related to normal brain development, the functionality of throat muscles, and the maturation of hearing, progressing through the stages of articulation, comprehension, and expression. Newborns express themselves by crying, and cooing vocalizations can be heard by 3–4 months of age. By the age of 7 months, infants begin to imitate sounds in early speech, and by 1 year, they can produce their first meaningful word. Between 1.5 to 2 years, they are capable of speaking short phrases. By 3 years, they are able to use simple sentences to narrate events from daily life. By 4 years, they are capable of answering simple questions about stories they have heard.

Development of Psychological Activities

Early Social Behaviors

At 2–3 months, infants start recognizing their parents through behaviors like smiling, ceasing crying, gazing, and vocalizing. By 3–4 months, babies exhibit socially responsive laughter. At 7–8 months, they begin showing wariness toward strangers and develop interest in sound-making toys. Stranger anxiety peaks between 9–12 months. By 12–13 months, infants enjoy interactive games like playing peek-a-boo or simple tricks. At 18 months, they begin to develop self-control and can play alone for extended periods when an adult is nearby. By 2 years of age, they no longer display stranger anxiety and can part from their parents more easily. After age 3, children are able to engage in play with peers.

Development of Attention

During infancy, attention is predominantly involuntary (naturally occurring and requiring no voluntary effort). As children grow older, deliberate attention (voluntary and goal-directed focus) becomes more evident. By 5–6 years of age, children are able to exercise greater control over their attention.

Development of Memory

Memory refers to the process of storing and retrieving learned information and involves three systems: sensory memory, short-term memory, and long-term memory. Long-term memory is further classified into recognition and recall. Recognition involves identifying previously encountered objects when they reappear, while recall refers to mentally reproducing previously learned information even in its absence. Infants under 1 year of age demonstrate recognition but lack recall abilities. With age, recall abilities gradually improve. Young children primarily remember information based on surface features and rely on rote memory. As they grow older, along with improved comprehension and language-based thinking skills, logical memory gradually develops.

Development of Thinking

Children begin to exhibit nascent thinking abilities after 1 year of age. Before the age of 3, thinking is limited to elementary visual-imagery thinking. After 3 years, preliminary abstract thinking starts to develop. From ages 6 to 11, children progressively learn methods like synthesis, analysis, categorization, and comparison as part of abstract thinking, gaining greater abilities for independent thought.

Development of Imagination

Newborns lack imagination. Between 1–2 years, imagination begins to emerge gradually. At 3–4 years, imagination develops rapidly, initially taking the form of free associations, though the content remains simple and limited. By 5–6 years, intentional imagination and creative imagination become richer and more complex.

Development of Emotions and Feelings

Newborns often exhibit negative emotions due to difficulty adapting to life outside the womb, demonstrated by restlessness and crying. However, actions such as feeding, holding, rocking, and stroking them can improve their mood. Infants' emotions tend to be short-lived, intense, changeable, and outwardly expressed, reflecting their genuine feelings. With age, children become more tolerant of unpleasant factors and develop the ability to regulate their emotions consciously, leading to emotional stability.

Development of Personality and Character

In infancy, all physiological needs depend on caregivers, leading to the establishment of trust and attachment to loved ones. During early childhood, children begin to walk independently and express their needs, giving rise to a sense of autonomy. However, dependence on loved ones persists, leading to alternating behaviors of defiance and reliance. By the preschool years, children are mostly self-sufficient in daily life, and their sense of initiative strengthens. However, failure in proactive behaviors may result in feelings of disappointment or guilt. During the school-age period, formal learning begins, and children place importance on achievements related to diligent studying. Failure to recognize their learning potential may lead to feelings of inferiority. Adolescence is marked by the maturation of physical growth and sexual development, increased social interactions, and enhanced psychological adaptability. However, emotional fluctuations may occur, and challenges related to emotional relationships, peer dynamics, career choices, moral evaluations, and life perspectives may lead to personality changes if improperly handled. Once formed, personality tends to become relatively stable.

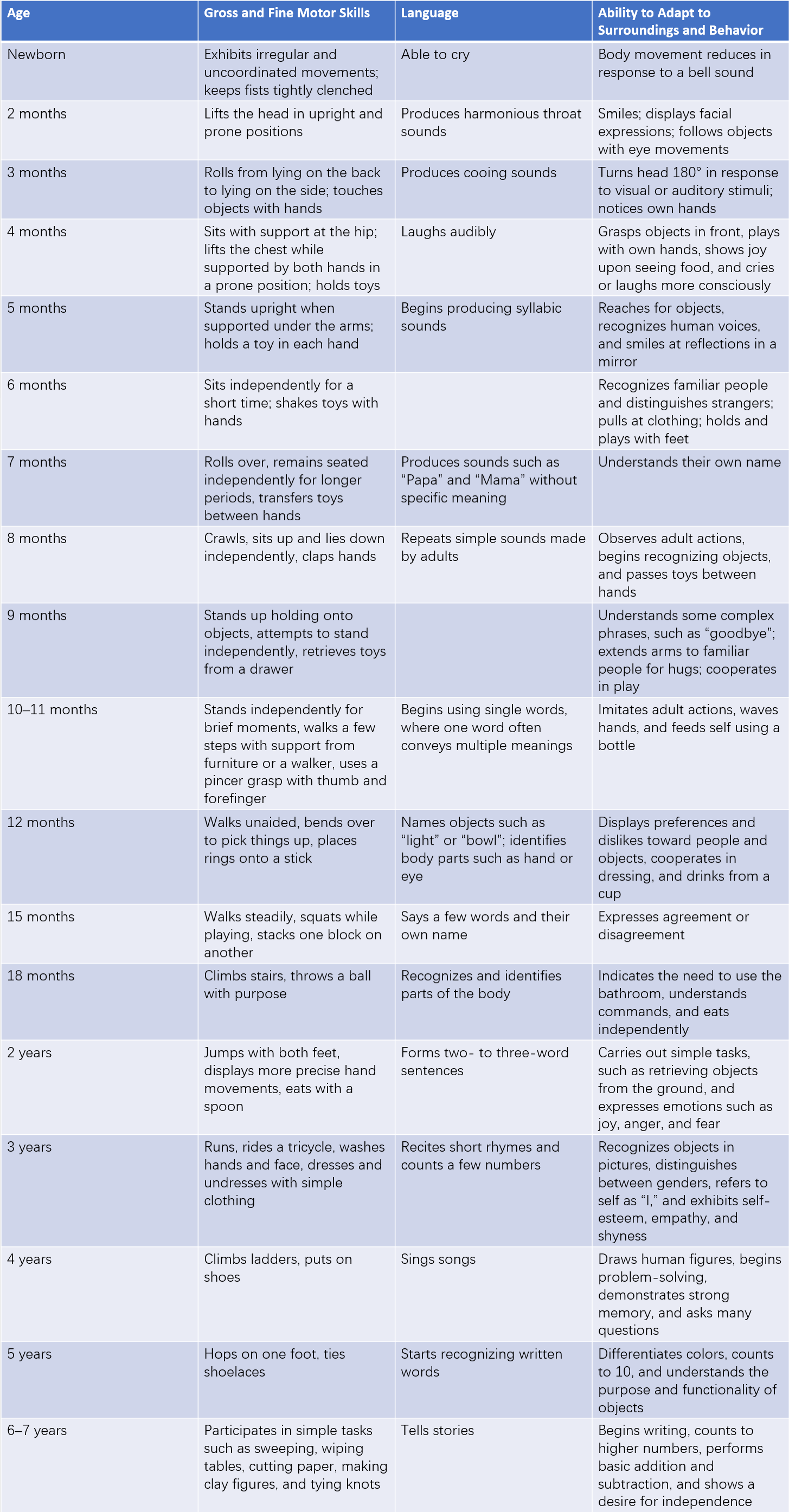

Table 1 Neuropsychological developmental progression in children