Amenorrhea refers to the absence of menstruation or cessation of menstrual periods for six months. Pathological amenorrhea can be classified into primary amenorrhea and secondary amenorrhea based on whether menstrual onset has occurred previously. Primary amenorrhea is diagnosed in individuals aged over 13 years without the development of secondary sexual characteristics or aged over 15 years with the development of secondary sexual characteristics but no menarche. Secondary amenorrhea is defined as the absence of menstruation in individuals with previous menstrual periods, including those with normal menstrual frequency who experience an absence of periods for three months or those with infrequent menstruation who have no periods for six months. Physiological amenorrhea, such as in prepuberty, pregnancy, lactation, or postmenopause, is not discussed in this context.

Amenorrhea is primarily categorized by the location of dysfunction into hypothalamic, pituitary, ovarian, or uterine amenorrhea. Developmental abnormalities in the lower reproductive tract may lead to obstructed menstrual outflow, resulting in pseudomenorrhea. Amenorrhea can also be classified based on gonadotropin (Gn) levels into hypo-gonadotropic amenorrhea and hyper-gonadotropic amenorrhea. Hypo-gonadotropic amenorrhea occurs due to hypothalamic or pituitary dysfunction causing decreased gonadotropin levels and subsequent ovarian dysfunction. Hyper-gonadotropic amenorrhea results from primary ovarian failure. The World Health Organization (WHO) categorizes amenorrhea into three types:

- Type I: Reduced endogenous estrogen (estradiol) production, normal or low follicle-stimulating hormone (FSH) levels, normal prolactin (PRL) levels, and no evident hypothalamic-pituitary abnormalities.

- Type II: Endogenous estrogen production is present and higher than the early follicular phase level, with normal FSH and PRL levels.

- Type III: Low endogenous estradiol levels and elevated FSH levels, indicative of ovarian failure.

Etiology

The establishment and maintenance of normal menstruation rely on the neuroendocrine regulation of the hypothalamic-pituitary-ovarian axis, the cyclical responses of the endometrium to sex hormones, and the patent lower reproductive tract. Dysfunction in any of these pathways may result in amenorrhea.

Primary Amenorrhea

Primary amenorrhea is relatively rare and often caused by genetic factors or congenital developmental defects. Approximately 30% of cases are associated with abnormalities in the reproductive tract. It can be divided into two categories based on the presence or absence of secondary sexual characteristics.

Primary Amenorrhea with Secondary Sexual Characteristics Present

Mayer-Rokitansky-Küster-Hauser (MRKH) Syndrome

Also known as congenital absence of the uterus and vagina, MRKH syndrome accounts for approximately 20% of cases of primary amenorrhea during adolescence. It is attributed to developmental malformations caused by abnormalities in the Müllerian ducts, potentially associated with genetic mutations and galactose metabolism disorders. Patients have a normal 46,XX karyotype, normal levels of sex hormones, and structurally normal ovaries, although their position may be atypical. Typical abnormalities include rudimentary or absent uterus and vagina, with only a shallow dimple present posterior to the urethra, often ending in a blind pouch. Around 15% of individuals have renal abnormalities (e.g., renal agenesis, pelvic kidney, or horseshoe kidney), 40% have duplicated urinary collecting systems, and 5–12% have skeletal abnormalities.

Reproductive Tract Obstruction

Obstruction of the menstrual outflow tract due to reproductive tract abnormalities can result in amenorrhea. Common causes include imperforate hymen, complete transverse vaginal septum, vaginal atresia, or severe labial adhesions. Patients typically have a 46,XX karyotype and normal ovarian function. Blood accumulates above the obstruction, leading to cyclic abdominal pain, uterine hematometra, or pyometra, and may cause endometriosis.

Androgen Insensitivity Syndrome (AIS)

This is formerly known as testicular feminization (note: the term "pseudo-hermaphroditism" is no longer used due to its stigmatizing connotation). Individuals have a 46,XY karyotype but exhibit defects in the androgen receptor gene located on the X chromosome. Their gonads are testes, typically located in the abdomen or inguinal canal. Testosterone levels are within the normal male range, but defects in androgen receptors prevent any biological effect, leading to a failure to develop male external genitalia. Testosterone is aromatized to estrogen, resulting in female phenotypic characteristics, including well-developed breasts during puberty. However, the nipples are underdeveloped, areolae are pale, and pubic and axillary hair are sparse. The vagina is blind and shorter than average, and the uterus and fallopian tubes are absent. AIS has two subtypes: complete AIS, characterized by female external genitalia with no pubic hair, and partial AIS, where pubic and axillary hair may be present but genital ambiguity exists.

True Hermaphroditism

This rare condition, now known as ovotesticular disorder of sex development (ovo-testicular DSD, OT-DSD), occurs at a rate of approximately 1 in 100,000 live births. Individuals possess both ovarian and testicular tissue, and karyotypes can include 46,XX, 46,XY, or mosaicism.

Resistant Ovarian Syndrome (ROS)

Also known as insensitive ovary syndrome, the condition is characterized by the following:

- The presence of numerous primordial and primary follicles within the ovaries.

- Elevated endogenous gonadotropins, particularly FSH (20–40 IU/L), with anti-Müllerian hormone (AMH) levels close to the average for women of the same age.

- Resistance to exogenous gonadotropins.

Clinical manifestations include primary amenorrhea and the presence of secondary sexual characteristics.

ROS is thought to be associated with gonadotropin receptor mutations, although the exact etiology remains unclear.

Primary Amenorrhea with Absent Secondary Sexual Characteristics

Hypogonadotropic Hypogonadism

This condition often results from insufficient hypothalamic secretion of GnRH or inadequate pituitary secretion of gonadotropins, leading to primary amenorrhea. It is referred to as idiopathic hypogonadotropic hypogonadism and exhibits significant clinical and genetic heterogeneity. More than 25 distinct pathogenic genes have been identified in approximately 50% of affected individuals. Roughly 50% of patients present with olfactory deficits (anosmia or hyposmia), which is classified as Kallmann syndrome. In these cases, the internal female genitalia develop normally.

Hypergonadotropic Hypogonadism

This condition mainly involves gonadal dysfunction related to genetic abnormalities or deficiencies in key enzymes for sex hormone synthesis. It is characterized by sex hormone deficiency and elevated LH and FSH levels.

Congenital Gonadal Dysgenesis

In this condition, the gonads are streak-like or underdeveloped, with absent or markedly reduced ovarian follicles. Clinically, it manifests as primary amenorrhea with an absence of secondary sexual development.

A. Turner Syndrome

A form of congenital gonadal dysgenesis with an incidence of 22.2 per 100,000 live female births. It results from sex chromosome abnormalities, typically with a karyotype of 45,XO or mosaic patterns such as 45,XO/46,XX or 45,XO/47,XXX. Individuals exhibit characteristics of primary amenorrhea, streak gonads, short stature, lack of secondary sexual development, a female external genital phenotype, an immature vagina, and a small uterus. Physical anomalies such as webbed neck, shield chest, low posterior hairline, high palate, low-set ears, fish-like mouth, and cubitus valgus are common, along with coarctation of the aorta, skeletal abnormalities, autoimmune thyroiditis, hearing loss, and hypertension. Approximately 90% of individuals with gonadal dysgenesis due to the loss of X chromosome material do not experience menarche. The remaining 10% may have residual ovarian follicles sufficient to trigger menarche, though pregnancy is rarely feasible, and early ovarian insufficiency is common.

B. 46,XX Pure Gonadal Dysgenesis

Individuals have no abnormalities in physical development, but the ovaries are streak-like and non-functional. The uterus is typically underdeveloped, secondary sexual characteristics are poorly developed, but the external genitalia are female.

C. 46,XY Pure Gonadal Dysgenesis (Swyer Syndrome)

This disorder is characterized by streak gonads and primary amenorrhea. Dysgenic testes fail to secrete testosterone and anti-Müllerian hormone (AMH), resulting in a female phenotypic appearance, including the presence of a uterus and fallopian tubes. Due to the presence of a Y chromosome, there is a significant risk (10–20%) of developing gonadoblastoma or dysgerminoma during adolescence or early adulthood, necessitating the removal of streak-like gonads once the diagnosis is confirmed.

D. XO/XY Gonadal Dysgenesis

This condition involves a karyotype of 45,XO/46,XY, with gonads that may include underdeveloped testes, ovaries, or a mix of streak gonads. Clinical features often resemble those seen in Turner syndrome. Individuals with this condition are at a heightened risk of gonadal tumors, prompting the recommendation for removal of the gonads prior to the onset of puberty.

Enzyme Deficiencies

Enzyme deficiencies interfere with sex hormone synthesis. Common types include:

- Patients with a 46,XY Karyotype: Deficiency of 17α-hydroxylase or 20α-lyase. These patients typically present with a female phenotype and clinical features, such as the absence of a uterus.

- Patients with a 46,XX Karyotype: Deficiency of 17α-hydroxylase. These individuals retain a uterus but lack secondary sexual characteristics.

Other Causes

Ovarian dysfunction may be caused by factors such as prepubertal radiotherapy or chemotherapy, galactosemia, mumps oophoritis, or autoimmune diseases.

Secondary Amenorrhea

Secondary amenorrhea is significantly more common than primary amenorrhea. Its causes are complex and can be classified based on the four major components that regulate the normal menstrual cycle: hypothalamus, pituitary, ovaries, and uterus. Among these, hypothalamic amenorrhea is the most frequent type.

Hypothalamic Amenorrhea

Hypothalamic amenorrhea refers to amenorrhea caused by functional or organic disorders of the central nervous system and hypothalamus, with functional causes being predominant. This condition is characterized by reduced or defective synthesis and secretion of GnRH in the hypothalamus, or abnormalities in its pulsatile secretion. This results in a decrease in FSH and LH secretion, classifying it as a form of hypogonadotropic amenorrhea. Functional hypothalamic amenorrhea (FHA) includes categories such as stress-induced amenorrhea, weight loss-induced amenorrhea, and exercise-induced amenorrhea.

Psychogenic Stress

Various acute or prolonged psychological stressors, including episodes of depression, anxiety, or tension, can lead to neuroendocrine dysfunction and subsequent amenorrhea. The mechanism may involve increased secretion of corticotropin-releasing hormone (CRH) and adrenocorticotropic hormone (ACTH) during stress. These hormones stimulate the release of endogenous opioids and dopamine, which inhibit hypothalamic GnRH secretion and pituitary gonadotropin release.

Weight Loss and Anorexia Nervosa

Anorexia nervosa and rapid weight loss can result in amenorrhea. Severe anorexia nervosa may occur alongside intense internal emotional conflicts or compulsive dieting to maintain body shape, presenting clinically as reduced appetite, extreme emaciation, and, in severe cases, life-threatening consequences. The mortality rate can reach 9%. Abrupt decreases in body weight are particularly sensitive to regulation by the central nervous system. Excessive dieting can lead to abnormally low body fat and decreased secretion of leptin from visceral fat cells, which weakens the inhibitory effect on neuropeptide Y (NPY) in the hypothalamus. Elevated NPY, in turn, inhibits the function of GnRH neurons in the hypothalamus and reduces the secretion of key neurohormones. Consequently, the anterior pituitary reduces its secretion of LH, FSH, ACTH, and other hormones, culminating in amenorrhea.

Excessive Exercise

Sustained intense physical exercise can cause amenorrhea, particularly in association with psychological stress, the degree of stress response, or reductions in body fat. Elevated basal metabolic rates following excessive physical activity suppress GnRH release, leading to a decrease in LH secretion and subsequent amenorrhea.

Medications

Long-term use of certain medications that suppress the central nervous system or hypothalamus can induce amenorrhea. Examples include steroidal contraceptives, phenothiazine derivatives (e.g., perphenazine, chlorpromazine), GnRH agonists or antagonists, chemotherapy agents, selective progesterone receptor modulators (e.g., mifepristone), weight-loss drugs, antihypertensives, and immunosuppressants. These drugs may inhibit hypothalamic GnRH secretion or suppress dopamine release in the hypothalamus, leading to increased prolactin secretion by the pituitary gland and subsequent amenorrhea. Drug-induced amenorrhea is typically reversible, with menstrual cycles often resuming 3–6 months after discontinuation of the drug.

Structural Damage and Inflammation

Organic hypothalamic amenorrhea can occur due to hypothalamic tumors, inflammation, or trauma. Among hypothalamic tumors, craniopharyngioma is the most common. Tumor growth may compress the hypothalamus and pituitary stalk, resulting in amenorrhea, genital atrophy, obesity, increased intracranial pressure, and visual disturbances.

Pituitary Amenorrhea

Pituitary amenorrhea arises from organic lesions or functional disturbances in the anterior pituitary, both of which can impair gonadotropin secretion and subsequently affect ovarian function.

Sheehan Syndrome

This condition results from severe postpartum hemorrhagic shock, which leads to ischemic necrosis of gonadotropin-secreting cells in the anterior pituitary. As a result, pituitary insufficiency develops, causing symptoms such as amenorrhea, lack of lactation, reduced libido, hair loss, regression of secondary sexual characteristics, genital atrophy, adrenal cortical and thyroid hypofunction (manifesting as cold intolerance, lethargy, and hypotension), and other symptoms, including severe localized pain behind the eyes, visual field defects, and vision loss. Basal metabolic rate is also reduced.

Pituitary Tumors

All types of pituitary adenomas located in the sella turcica can potentially influence hormone secretion. The most common type is prolactin-secreting adenomas (prolactinomas). The severity of amenorrhea is related to the degree to which prolactin inhibits hypothalamic GnRH secretion and pituitary gonadotropin release. Other types include growth hormone-secreting adenomas, thyroid-stimulating hormone-secreting adenomas, adrenocorticotropic hormone-secreting adenomas, and non-functioning pituitary adenomas. These tumors reduce gonadotropin secretion either by secreting hormones that suppress GnRH release or by directly compressing gonadotropin-secreting cells.

Empty Sella Syndrome

In this condition, congenital defects in the sella turcica diaphragm, tumors, or surgical damage allow cerebrospinal fluid to enter the sella turcica, compressing the pituitary gland. The pituitary gland shrinks, and the sella turcica enlarges, resulting in what is known as an empty sella. Compression of the pituitary stalk by cerebrospinal fluid disrupts the portal venous circulation between the hypothalamus and the pituitary gland, leading to symptoms such as amenorrhea, lactation, and hyperprolactinemia.

Pituitary Inflammation

Lymphocytic hypophysitis during the perinatal period can lead to pituitary insufficiency, causing amenorrhea.

Ovarian Amenorrhea

Ovarian amenorrhea arises from ovarian dysfunction, leading to reduced levels of sex hormones and preventing cyclical changes in the endometrium. This type of amenorrhea is classified as hypergonadotropic amenorrhea.

Ovarian Function Decline

The loss of ovarian function caused by the depletion of ovarian follicles or a decline in the quality of residual follicles is referred to as ovarian function decline. Common risk factors include genetic predisposition, immune disorders, infections, endocrine abnormalities, iatrogenic damage (such as gonadal damage due to radiotherapy or chemotherapy, or surgery affecting ovarian blood supply), environmental influences, and psychosocial factors. This condition is characterized by elevated gonadotropin levels and low estrogen levels, with clinical manifestations including secondary amenorrhea and perimenopausal symptoms. Premature ovarian insufficiency (POI) refers to diminished ovarian function before the age of 40 due to various causes, often leading to amenorrhea and eventually progressing to premature ovarian failure (POF).

Functional Ovarian Tumors

Ovarian granulosa cell tumors and theca cell tumors, which secrete estrogen, may cause continuous estrogen release. This inhibits ovulation, leading to sustained endometrial proliferation and resulting in amenorrhea.

Sertoli-Leydig cell tumors, which produce androgen, cause excessive secretion of androgen, suppressing the hypothalamic-pituitary-ovarian axis function and leading to amenorrhea. Clinically, such cases are characterized by pronounced virilization with rapid symptom progression.

Polycystic Ovary Syndrome (PCOS)

This syndrome is defined by chronic anovulation and hyperandrogenemia. Clinical features include infrequent menstruation or amenorrhea, infertility, hirsutism, and obesity.

Uterine Amenorrhea

This type of amenorrhea can be either congenital or acquired. Acquired uterine amenorrhea occurs due to damage to the basal layer of the endometrium or adhesions within the uterine cavity or cervical canal, which result in amenorrhea. The hypothalamic-pituitary-ovarian (HPO) axis remains intact, and secondary sexual characteristics are normal.

Uterine Cavity Adhesions

Endometrial damage and adhesion syndrome (Asherman syndrome) typically arise from excessive curettage due to postpartum bleeding or post-abortion bleeding, as well as overzealous surgical abortions. Post-abortion infections, puerperal infections, Mycobacterium tuberculosis infection of the endometrium, or infections following various intrauterine surgeries can lead to endometrial damage and subsequent amenorrhea. Other uterine surgeries, such as uterine repair procedures, myomectomies, cesarean sections, or pelvic radiotherapy, can also cause secondary damage to the endometrium.

Cervical Adhesions

Cervical adhesions may result from procedures such as cervical dilation and curettage, cold knife conization, loop electrosurgical excision procedures (LEEP), or infections. These conditions may lead to postoperative scarring, cervical stenosis, or adhesions, causing amenorrhea.

Additionally, dysfunction of other endocrine glands—such as the thyroid, adrenal gland, and pancreas—may lead to secondary amenorrhea. Common related conditions include hypothyroidism, hyperthyroidism, adrenal cortical hyperfunction, and adrenal cortical tumors.

Diagnosis

Amenorrhea is a symptom rather than a disease. The diagnostic process involves identifying the underlying cause of amenorrhea, determining the site of the pathology, and then establishing the specific condition responsible.

Medical History

A detailed medical history is essential. This includes questions about the menstrual history, such as age at menarche, menstrual cycle regularity, duration and volume of menstrual bleeding, the length of the amenorrhea, and any accompanying symptoms. Information about potential triggers like psychological stress, environmental changes, weight fluctuations, intense exercise, related diseases, or medication use is important. Symptoms such as cyclic pelvic pain, hirsutism, acne, hot flashes, sweating, new-onset headaches, visual changes, or galactorrhea should also be noted. Past surgical history, postoperative infections, or complications are relevant, particularly for women with primary amenorrhea. In married women, obstetric history, including postpartum complications, should be investigated. For primary amenorrhea, secondary sexual development should be assessed along with growth and developmental history, the presence of congenital defects, other diseases, and family history. Any prior examinations or treatments should also be reviewed.

Physical Examination

Observation of mental status and overall physical development is necessary, including intelligence, height, weight, limb-to-trunk ratio, skin pigmentation, facial features, secondary sexual characteristics, and signs of physical developmental abnormalities. The thyroid should be checked for enlargement, and breast examination should assess lactation. Hair distribution and the presence of inguinal or abdominal masses should also be evaluated. In cases of primary amenorrhea with underdeveloped secondary sexual characteristics, the sense of smell should also be assessed. Gynecological examination should focus on the development of the internal and external genitalia, the presence of congenital defects or malformations, and inguinal or pelvic masses. For sexually active women, an assessment of vaginal and cervical mucus can provide insights into estrogen levels.

Laboratory and Auxiliary Examinations

For women of reproductive age, pregnancy should first be ruled out. Based on findings from the medical history and physical examination, an initial understanding of the cause and location of the pathology can guide further, targeted diagnostic testing.

Hormonal Assays

Hormonal testing plays a critical role in evaluating amenorrhea. Interpretation should not rely on a single result but rather consider the patient's overall clinical presentation and other test findings.

Sex Hormones

Measurements include estradiol (E2), progesterone (P), and testosterone.

Elevated serum progesterone levels indicate ovulation.

Low estrogen levels suggest ovarian dysfunction or failure.

Elevated testosterone levels may indicate polycystic ovary syndrome (PCOS) or ovarian Sertoli-Leydig cell tumors. Total serum testosterone levels are typically measured, so a normal testosterone result does not exclude PCOS, which requires consideration of symptoms and other findings.

Pituitary Hormones

Elevated serum prolactin (PRL) levels may suggest a pituitary tumor.

Concurrent elevation of PRL and thyroid-stimulating hormone (TSH) suggests hypothyroidism as a cause of amenorrhea.

Low FSH and LH levels, especially LH <5 IU/L, indicate hypothalamic or pituitary dysfunction.

Elevated FSH levels suggest hypergonadotropic hypogonadism, but ovulatory FSH peaks should be excluded. Normal FSH levels require further evaluation in combination with other findings.

Other Hormones

Thyroid-stimulating hormone (TSH) should be measured in most cases of amenorrhea.

In patients with obesity, hirsutism, or acne, additional tests include insulin, androgen levels, oral glucose tolerance testing (OGTT), and insulin release testing to assess for insulin resistance, hyperandrogenemia, or congenital adrenal hyperplasia.

Cushing syndrome can be evaluated with tests such as 24-hour urinary free cortisol or the 1 mg dexamethasone suppression test.

Anti-Müllerian hormone (AMH) can be tested to assess ovarian reserve.

For those taking hormone-related medications, hormonal levels should be assessed after discontinuing the drugs for at least two weeks.

Functional Testing

Progestational Challenge

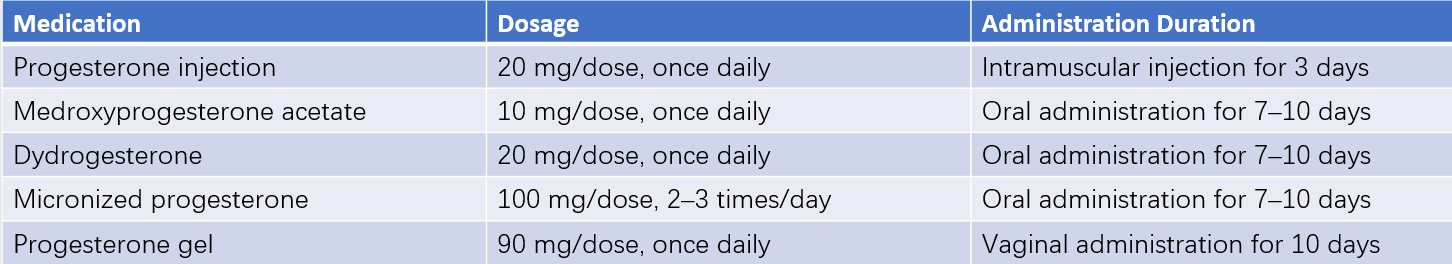

This is used to evaluate estrogen levels in the body by administering exogenous progestins such as progesterone or medroxyprogesterone acetate.

Withdrawal bleeding after discontinuation (a positive response) suggests that the endometrium has been exposed to sufficient estrogen and that the outflow tract is patent.

No withdrawal bleeding (a negative response) may indicate low endogenous estrogen levels, uterine pathology, lower genital tract abnormalities, or pregnancy. Further sequential estrogen-progestin testing is required after ruling out pregnancy.

Table 1 Progestational challenge test medication guide

Sequential Estrogen-Progestin Test

This is used for cases of amenorrhea with negative progestational challenge results.

Oral estrogen (e.g., estradiol valerate, 17β-estradiol, or conjugated estrogen) is administered for 21 days, followed by the addition of progestins for 10 days. A positive withdrawal bleed indicates normal endometrial function, ruling out uterine-related causes of amenorrhea. The cause is attributed to low estrogen levels, requiring further investigation. Persistent negative withdrawal testing suggests uterine or lower genital tract abnormalities. Combining this test with gynecological ultrasound and hormonal assays allows for a more effective diagnostic approach.

Pituitary Stimulation Test (GnRH Stimulation Test)

This evaluates the pituitary response to GnRH administration.

An increase in LH suggests normal pituitary function and points to hypothalamic pathology.

Minimal or no increase in LH even after repeated testing indicates pituitary dysfunction, such as Sheehan's syndrome.

Imaging Studies

Ultrasound

This evaluates the presence, size, and shape of the uterus, endometrial thickness, ovarian size, morphology, follicle count, and ovarian tumors, if any.

Three-dimensional ultrasound is particularly helpful for diagnosing uterine malformations or intrauterine adhesions.

Patients with pronounced masculinization should undergo ovarian and adrenal gland ultrasound or MRI to rule out tumors.

MRI or CT

This is useful for assessing pelvic and central nervous system lesions, including abnormalities in the hypothalamus, pituitary microadenomas, ovarian tumors, or uterine and vaginal developmental abnormalities.

Hysterosalpingography

This assesses uterine developmental anomalies, intrauterine pathologies, and adhesions.

Hysteroscopy

This is used to evaluate and rule out conditions like intrauterine adhesions.

Chromosome Analysis

This is essential for diagnosing primary amenorrhea and distinguishing gonadal dysgenesis.

This is indicated for cases of high gonadotropin levels, short stature, webbed neck, and elevated testosterone, particularly when sex development disorders are suspected. Advanced sequencing methods, such as whole-genome sequencing, may be considered under specific circumstances.

Bone Mineral Density (BMD)

Prolonged low-estrogen states can result in bone loss and osteoporosis. Measuring BMD aids in diagnosis and management.

Other Tests

Basal body temperature monitoring and endometrial biopsy may provide additional information.

Endometrial cultures should be performed if tuberculosis or schistosomiasis is suspected.

Bone age assessment, when necessary, can help identify the underlying cause and guide treatment strategies.

Treatment

The primary principle of treatment is to address the underlying cause. Hormone therapy plays a central role in promoting the development of secondary sexual characteristics, restoring menstruation, supporting fertility, and maintaining both reproductive and overall health in women.

General Treatment

General systemic diseases should be actively treated, and efforts should be made to improve the overall physical condition by ensuring adequate nutrition and maintaining a standard body weight. For amenorrhea caused by excessive exercise, physical activity should be adjusted. Psychological therapy may be necessary for amenorrhea resulting from stress or psychological factors to alleviate mental tension and anxiety. Tumor-related causes, polycystic ovary syndrome (PCOS), or other conditions leading to amenorrhea should be treated based on the specific etiology.

Endocrine Therapy

After identifying the site of pathology and the underlying cause, endocrine therapies can be used to supplement hormone deficiencies or counteract hormonal excess. For individuals with fertility needs, ovulation induction may be considered.

Hormonal Replacement Therapy

The goal is to maintain overall and reproductive health, including cardiovascular health, bone metabolism, neurological function, and the urogenital system. Treatment also promotes and sustains the development of secondary sexual characteristics and menstruation. The main therapeutic regimens include the following:

Estrogen Replacement Therapy

Options include estradiol valerate (1 mg/day), micronized 17β-estradiol (1–2 mg/day), or topical estradiol gel (1.25–2.5 g/day).

For adolescents with hypogonadism who have not yet achieved their target height, the treatment should start with low doses such as estradiol valerate 0.5 mg or 17β-estradiol 0.5 mg, administered every other day or daily. Once the target height is reached, the dosage can be gradually increased to adult levels to further promote secondary sexual development.

Post-uterine development, progesterone should be added periodically based on the degree of endometrial proliferation, or sequential estrogen-progestin therapy should be adopted.

For adult patients with low estrogen levels and amenorrhea, estradiol valerate (1–2 mg/day) or 17β-estradiol (1–2 mg/day) can be initially used to promote and maintain overall health and secondary sexual development. Once uterine development is achieved, progesterone or sequential estrogen-progestin therapy is also recommended.

Artificial Cycle Therapy

This is suitable for patients with a uterus. Estrogen is administered continuously for 21 days, with progesterone added during the last 10 days. Options include dydrogesterone (10–20 mg/day), micronized progesterone (200–300 mg/day), or medroxyprogesterone acetate (6–10 mg/day).

For adolescent females, natural or near-natural progesterones, such as dydrogesterone or micronized progesterone, are preferred to support the recovery of hypothalamic-pituitary-ovarian axis function.

Progestin Therapy

This is applicable for individuals with some endogenous estrogen levels. Progestins such as dydrogesterone (10–20 mg/day) or micronized progesterone (200–300 mg/day) can be administered orally for 10–14 days during the latter half of the menstrual cycle (or 14–20 days after withdrawal bleeding). This helps prevent endometrial hyperplasia or related disorders.

Oral Contraceptives

Estrogen-progestin supplementation can inadvertently lead to pregnancy in some cases, so oral contraceptives may serve as an effective option for women seeking both pregnancy prevention and treatment for anovulatory amenorrhea.

For PCOS patients with significant hyperandrogenemia or elevated androgen symptoms, oral contraceptives can also be considered as part of the treatment.

46, XY Disorders of Sexual Development in Adolescents with a Female Gender Identity

Long-term estrogen replacement therapy is necessary after gonadectomy. Progesterone may be added in patients with a uterus.

Ovulation Induction Therapy

This option applies to patients who have fertility needs.

For hypogonadotropic hypogonadism-related amenorrhea, estrogen therapy is used to stimulate the development of reproductive organs. Once the endometrium becomes responsive to estrogen and progestin, human menopausal gonadotropin (hMG) combined with human chorionic gonadotropin (hCG) can be administered to promote follicular development and induce ovulation. However, this carries a risk of ovarian hyperstimulation syndrome (OHSS), which can be life-threatening in severe cases. Ovulation induction with gonadotropins requires experienced physicians and monitoring of ultrasound and hormone levels.

For amenorrhea patients with normal FSH and PRL levels and some endogenous estrogen, clomiphene citrate is typically the first-line ovulation induction drug of choice.

For patients with ovarian failure and elevated FSH levels, ovulation induction drugs are generally not recommended.

Other Pharmacological Treatments

Bromocriptine

As a dopamine receptor agonist, bromocriptine binds directly to pituitary dopamine receptors, suppressing PRL secretion and restoring ovulation.

Bromocriptine also inhibits the growth of prolactin-secreting pituitary tumor cells. Tumor size decreases significantly in sensitive patients within three months of treatment, and microadenomas typically do not require surgical intervention.

Corticosteroids

These are used for amenorrhea caused by congenital adrenal hyperplasia. Common options include prednisone or dexamethasone.

Thyroid Hormones

Thyroid preparations are used for amenorrhea associated with hypothyroidism.

For patients with pathological conditions of other endocrine glands, treatment should be guided by an endocrinologist to address the specific endocrine disorder.

Assisted Reproductive Technology

For patients with fertility needs who fail to achieve pregnancy after ovulation induction, or those with concomitant tubal issues or male factor infertility, assisted reproductive technologies may be considered. It is essential to assess the genetic risk to the offspring of women with amenorrhea. Genetic counseling must be conducted by appropriately qualified institutions and professionals.

Surgical Treatment

Specific surgical interventions are used to address various organic causes of amenorrhea.

Congenital Genital Anomalies

Conditions such as imperforate hymen, transverse vaginal septum, or vaginal atresia can be treated with surgical incision or reconstruction to allow normal menstrual blood flow. Patients with cervical agenesis who are unsuitable for surgical correction usually require a hysterectomy. Uterus transplantation has been explored as one treatment option to enable patients with Mayer-Rokitansky-Küster-Hauser (MRKH) syndrome to become biological mothers, with successful childbirth cases already reported.

Asherman Syndrome

Treatment often involves hysteroscopic separation of intrauterine adhesions under direct visualization. A uterine cavity stent is placed following the procedure, and high-dose estrogen therapy is administered (e.g., oral estradiol valerate at 2–4 mg/day for 21 days, followed by 10 days of progesterone supplementation). The medication regimen is repeated every 3–6 months based on withdrawal bleeding volume. Cervical stenosis and adhesions can typically be treated through cervical dilation procedures.

Tumors

For ovarian tumors, surgical treatment is recommended upon confirmation of the diagnosis.

In pituitary tumors, treatment plans depend on the tumor's location, size, and nature. Prolactinomas are often managed with medication, while surgery is reserved for cases where pharmacological treatment is ineffective or when large adenomas cause compressive symptoms.

Other central nervous system tumors are typically treated using surgery and/or radiotherapy.

Gonads in patients with hypergonadotropic amenorrhea containing Y chromosome material are prone to neoplastic changes. Gonadectomy is generally recommended following a definitive diagnosis.

Patient Education and Long-Term Management

Patients require thorough counseling regarding the diagnosis, long-term implications, and treatment options for their condition. Hormone therapy necessitates long-term follow-up and management, which includes monitoring abnormal laboratory parameters, addressing new symptoms or complications, adjusting treatment plans, and discussing fertility-related issues.