Ovulatory abnormal uterine bleeding (ovulatory AUB) is primarily caused by luteal dysfunction and is less common than anovulatory AUB. It most frequently occurs in women of reproductive age. Patients with ovulatory AUB experience regular ovulation and clinically recognizable menstrual cycles. Luteal dysfunction includes inadequate luteal function and irregular shedding of the endometrium.

Inadequate Luteal Function

During the menstrual cycle, follicular development and ovulation occur, but insufficient progesterone secretion during the luteal phase or premature luteal regression leads to poor endometrial secretory response and a shortened luteal phase.

Pathogenesis

Adequate levels of follicle-stimulating hormone (FSH) and luteinizing hormone (LH), as well as a proper ovarian response to LH, are prerequisites for a functional luteal phase. Luteal insufficiency can arise from various factors:

- A deficiency in FSH during the follicular phase can result in slow follicular development and reduced estrogen secretion, leading to insufficient positive feedback on the pituitary and hypothalamus.

- A low LH surge post-ovulation, or insufficient LH pulsatility, may result in incomplete luteal development and reduced progesterone secretion.

- Poor follicular development may impair granulosa cell luteinization after ovulation, leading to inadequate progesterone secretion.

Physiological factors such as early puberty, postpartum, or perimenopause may also contribute to inadequate luteal function.

Pathology

Endometrial histology typically shows secretory endometrium, with poor glandular secretory activity and inconspicuous stromal edema. There may also be asynchronous development of glands and stroma. Endometrial biopsy reveals a delayed secretory response by approximately two days.

Clinical Manifestations

Patients often present with shortened menstrual cycles or premenstrual bleeding. In some cases, the menstrual cycle remains within the normal range, but the follicular phase is prolonged and the luteal phase is shortened (less than 11 days). This can reduce fertility, leading to difficulties in conception or early pregnancy loss.

Diagnosis

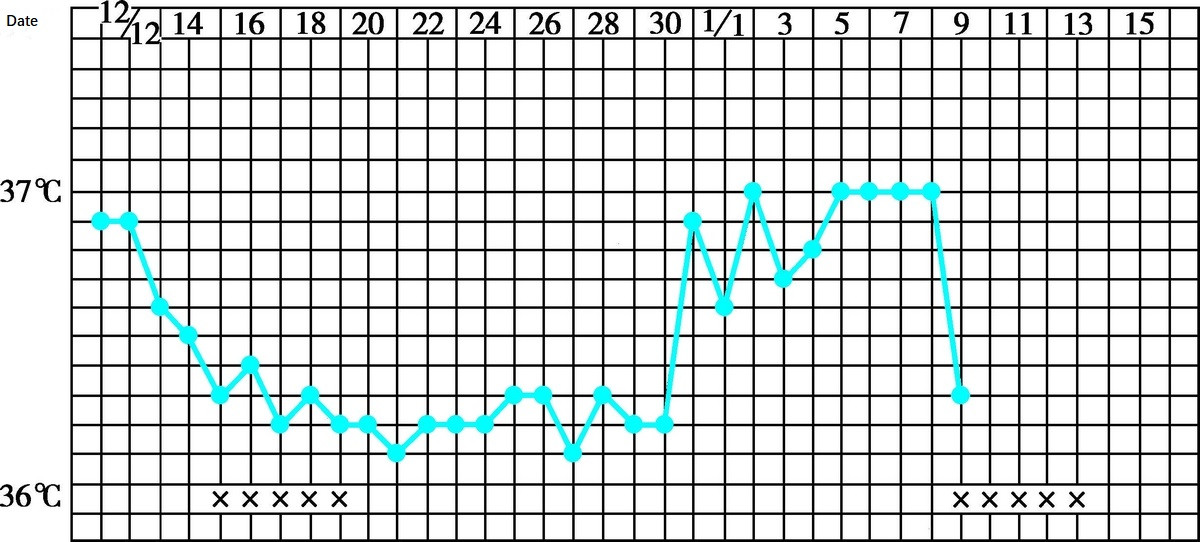

The diagnosis is based on clinical history and the exclusion of organic reproductive tract abnormalities during gynecological examination. Basal body temperature (BBT) typically shows a biphasic pattern, but the high-temperature phase lasts fewer than 11 days. An endometrial biopsy showing a secretory delay of two days supports the diagnosis.

Figure 1 Biphasic basal body temperature (short luteal phase)

Treatment

Treatment regimens include:

- Improvement of Follicular Development: In patients with fertility needs, ovulation induction is employed to enhance follicular development and luteal function. Treatments may include clomiphene, letrozole, or human menopausal gonadotropin (hMG).

- Promotion of Mid-Cycle LH Surge: After follicular maturation, injections of 5000–10,000 units of human chorionic gonadotropin (hCG) can be administered intramuscularly.

- Luteal Function Stimulation Therapy: Initiation of intramuscular injections of 1000–2000 units of hCG every other day, starting after the BBT rise, for a total of five doses.

- Luteal Function Supplementation Therapy: Natural progesterone preparations are commonly used, such as oral dydrogesterone (10–20 mg/day), micronized progesterone (200–300 mg/day), or intramuscular injections of progesterone (10 mg/day), starting after ovulation for 10–14 days.

- Oral Contraceptives: For patients with contraceptive needs, cyclic use of oral contraceptives for three cycles is suggested, with treatment adjustments for relapsing conditions up to six cycles if needed.

Irregular Shedding of the Endometrium

Despite regular ovulation and proper luteal development, prolonged luteal regression disrupts the normal sequence of endometrial shedding, resulting in prolonged menstruation.

Pathogenesis

Disruption of the hypothalamic-pituitary-ovarian axis regulation or defective luteolysis may lead to incomplete luteal regression. The endometrium remains continuously influenced by progesterone, preventing timely, complete shedding.

Pathology

Under normal circumstances, the secretory endometrium is completely shed by the third to fourth day of menstruation. When luteal regression is incomplete, secretory endometrial tissue may still be present on the fifth to sixth day of menstruation. Mixed-type endometrial histology is often observed, with retained secretory endometrium, hemorrhagic necrotic tissue, and newly proliferated endometrium coexisting.

Clinical Manifestations

The menstrual cycle is typically normal, but menstruation is prolonged, lasting 9–10 days. The amount of bleeding can vary, from light to heavy.

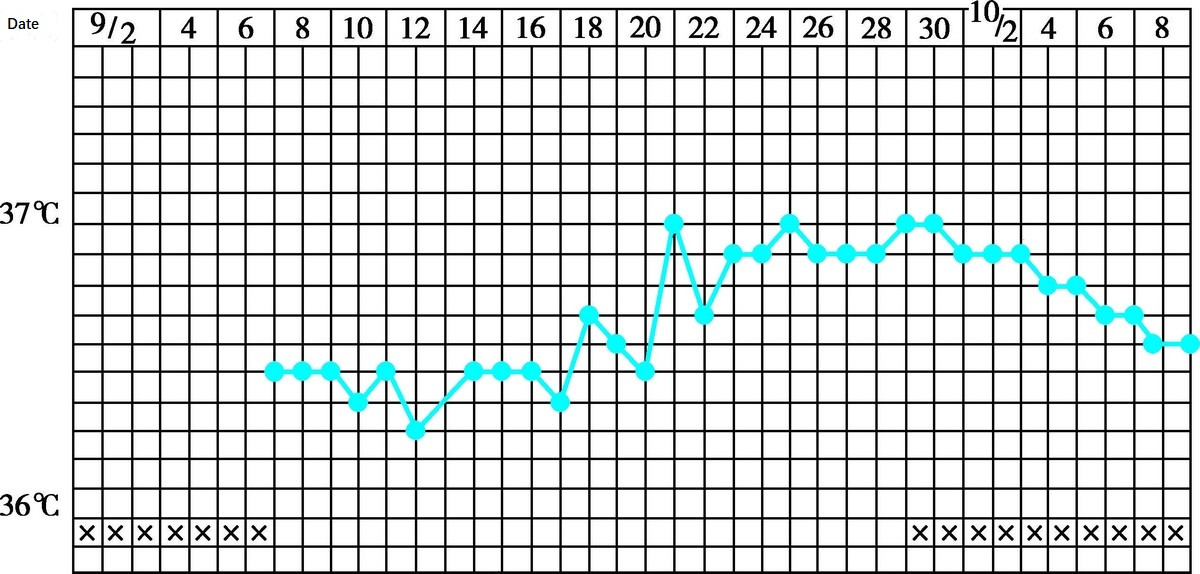

Diagnosis

Clinical presentation includes prolonged menstruation. BBT displays a biphasic pattern, but the return to the baseline temperature is slow. Diagnostic curettage performed on the fifth to seventh day of menstruation confirms persistent secretory changes in the endometrium.

Figure 2 Biphasic basal body temperature (irregular shedding of endometrium)

Treatment

Treatment regimens include:

- Progestin Therapy: Progestins, such as dydrogesterone, may be administered orally starting on day 1–2 post-ovulation or 10–14 days before the next menstrual period. Alternatively, intramuscular injections of progesterone may be used. Progestin withdrawal facilitates synchronized endometrial shedding and significantly shortens the duration of menstruation.

- Human Chorionic Gonadotropin (hCG): The regimen is similar to that used for inadequate luteal function and supports luteal function.

- Combined Oral Contraceptives (COCs): COCs regulate the cycle and suppress ovulation. This approach is particularly suitable for patients with contraceptive needs, with treatment cycles lasting 3–6 months.