Pathophysiology and Etiology

Normal menstruation is cyclic endometrial shedding and bleeding regulated by the hypothalamic-pituitary-ovarian (HPO) axis. About two weeks after ovulation, the regression of the corpus luteum causes a withdrawal of estrogen and progesterone, leading to the breakdown and shedding of the endometrial functional layer, resulting in menstrual bleeding. Normal menstrual cycles are characterized by regularity, self-limitation, and predictable timing, duration, and volume of blood loss. However, various internal and external factors, such as psychological stress, malnutrition, metabolic disorders, chronic illnesses, abrupt environmental or climate changes, dietary imbalances, excessive physical activity, alcohol abuse, or certain medications, can disrupt the HPO axis or impair end-organ responses, causing menstrual irregularities.

Anovulatory abnormal uterine bleeding (AUB) is common during adolescence and the perimenopausal transition, though it can also occur in reproductive-age women. During adolescence, the HPO axis is not fully mature, with defects in the central nervous system's feedback response to estrogen. This immaturity prevents stable cyclic regulation between the hypothalamus, pituitary, and ovaries. Follicle-stimulating hormone (FSH) remains persistently low, and no luteinizing hormone (LH) surge necessary for ovulation occurs. While ovarian follicles may grow, they often regress prematurely, leading to follicular atresia and an absence of ovulation.

In the perimenopausal transition, ovarian function declines as the follicular pool becomes depleted. Remaining follicles exhibit reduced responsiveness to gonadotropins, resulting in low estrogen production and an absence of the preovulatory LH surge, which prevents ovulation. In reproductive-age women, factors such as stress, obesity, or polycystic ovary syndrome (PCOS) may also lead to anovulation.

Anovulation resulting from any cause leads to sustained endometrial exposure to unopposed estrogen without the counteraction of progesterone. This may trigger estrogen breakthrough bleeding (BTB), which occurs in the following two forms:

- Low-Level Estrogen Breakthrough Bleeding: Continuous low-level estrogen stimulation maintains the endometrium at a threshold level, causing intermittent light bleeding. Slow endometrial repair due to minimal stimulation leads to prolonged bleeding episodes.

- High-Level Estrogen Breakthrough Bleeding: Sustained high estrogen levels cause excessive endometrial proliferation. Without progesterone, the thickened endometrium becomes fragile and prone to localized shedding, which is difficult to repair. This presents clinically as either prolonged light spotting or heavy bleeding following a period of amenorrhea.

Another mechanism of bleeding in anovulatory AUB is estrogen withdrawal bleeding. Prolonged stimulation of the endometrium by unopposed estrogen leads to continuous endometrial proliferation. When a group of ovarian follicles undergoes atresia, or when high estrogen levels suppress FSH via negative feedback, a subsequent sudden drop in estrogen levels causes endometrial shedding. This type of bleeding resembles withdrawal bleeding caused by exogenous estrogen cessation.

Anovulatory AUB is also associated with defects in the endometrium's self-limiting mechanisms for bleeding. The following features may contribute:

- Increased Tissue Fragility: Unopposed estrogen stimulation causes insufficient endometrial stromal transformation, resulting in fragile tissue prone to spontaneous rupture and bleeding.

- Incomplete Endometrial Shedding: Irregular and incomplete endometrial sloughing occurs due to fluctuating estrogen levels. While one region of the endometrium may heal under estrogen stimulation, another area may simultaneously undergo shedding and bleeding. This focalized breakdown in persistently hyperplastic endometrium hampers effective tissue regeneration and repair.

- Abnormal Vascular Structure and Function: Sustained estrogen exposure increases the density of ruptured capillaries within the endometrium. These fragile, poorly formed small blood vessels lack proper spiralization and contraction, leading to prolonged bleeding duration and increased volume.

- Coagulation and Fibrinolysis Abnormalities: Repeated tissue damage activates fibrinolysis, resulting in excessive fibrin breakdown and intensified fibrinolytic activity within the endometrium.

- Abnormal Vasoactive Factors: During the proliferative phase, the levels of prostaglandin E2 (PGE2) in the endometrium are higher than those of PGF2α. In hyperplastic endometrial tissue, PGE~2 levels and sensitivity are further elevated, resulting in increased vascular dilation and enhanced bleeding.

Pathological Changes in the Endometrium

In AUB-O (abnormal uterine bleeding due to ovulatory dysfunction), the endometrium can display varying degrees of hyperplastic changes depending on the levels and duration of estrogen exposure, as well as the sensitivity of the endometrium to estrogen. In rare cases, atrophic changes may also occur.

Proliferative Endometrium

The histological appearance of the endometrium is consistent with the normal proliferative phase of the menstrual cycle. However, it retains the proliferative-phase morphology during the latter half of the cycle and even during menstruation.

Endometrial Hyperplasia

According to the 2020 WHO Classification of Female Genital Tumors, endometrial hyperplasia is categorized based on structural and cytological characteristics:

- Endometrial Hyperplasia Without Atypia: Refers to excessive proliferation of the endometrium that exceeds the late proliferative phase of normal cycles. The gland-to-stroma ratio increases, with glands appearing irregular but resembling those seen in the proliferative phase. Nuclei remain uniform with no atypia. This category includes what was formerly termed simple hyperplasia and complex hyperplasia, with a very low risk (1%–3%) of progression to endometrial cancer.

- Atypical Endometrial Hyperplasia (AEH) / Endometrioid Intraepithelial Neoplasia (EIN): Characterized by hyperplasia of the endometrial glands with cellular atypia. The glandular proliferation far exceeds the stroma, exhibiting cytological features similar to well-differentiated endometrioid carcinoma but lacking definitive stromal invasion. Glandular architecture shows back-to-back patterns and intraglandular papillary structures. Cellular atypia includes stratified epithelium, round or oval nuclei with a vacuolated chromatin pattern, and eosinophilic or bicolored cytoplasm. The risk of progression to endometrial cancer ranges from 25% to 33%, making it a precancerous lesion typically categorized as AUB-M.

Atrophic Endometrium

The atrophic endometrium is thin, with fewer and smaller glands. The glandular ducts are narrow and straight, lined by a single layer of cuboidal or low columnar epithelial cells. The stroma is scant and dense, with an increased collagen content. This type is less commonly seen in AUB-O patients.

Clinical Manifestations

Most women with anovulation present with menstrual irregularities, marked by the loss of normal cycle periodicity and self-limiting bleeding. The bleeding intervals vary widely, ranging from a few days to several months. The amount of bleeding also varies, with some individuals experiencing only spotting while others have heavy, prolonged bleeding that may not resolve spontaneously, potentially leading to anemia or even shock. Bleeding episodes are often not accompanied by abdominal pain or other discomfort, though patients may exhibit symptoms such as acne, hirsutism, obesity, or galactorrhea. Bleeding patterns are influenced by serum estrogen levels, the rate of estrogen decline, the duration of estrogen exposure to the endometrium, and endometrial thickness.

Diagnosis

Other causes of AUB must be excluded before making a diagnosis.

History Taking

A detailed medical history is important, including the patient's age, menstrual history, marital and reproductive history, and use of contraception. Pregnancy must be ruled out. Conditions causing abnormal uterine bleeding, such as tumors or infections of the reproductive tract, hematologic disorders, and liver, kidney, or thyroid diseases, must be considered, as well as any recent medication use that may interfere with ovulation. Symptoms should be assessed to confirm specific bleeding patterns. Potential triggers, such as environmental changes, weight fluctuations, or psychological stress, should also be considered.

Physical Examination

A comprehensive physical examination includes both general and gynecologic assessments. General findings such as obesity, emaciation, goiter, hirsutism, galactorrhea, bruises, or hyperpigmentation should be noted to provide clues about the underlying condition. Gynecological examination is essential to exclude structural and pathological abnormalities of the vagina, cervix, and uterus, and to determine the source of bleeding.

Laboratory and Diagnostic Tests

The main objectives are to confirm anovulation, assess severity, rule out other causes, and identify potential comorbidities.

- Complete Blood Count (CBC): Assesses the severity of bleeding, with coagulation profiles being considered based on clinical judgment.

- Urine Pregnancy Test or Serum hCG Testing: Excludes pregnancy-related conditions.

- Ultrasound Examination: Provides information about the endometrial thickness and echogenicity, and identifies intrauterine space-occupying lesions or other structural abnormalities in the reproductive tract. It can also assess ovarian follicular status.

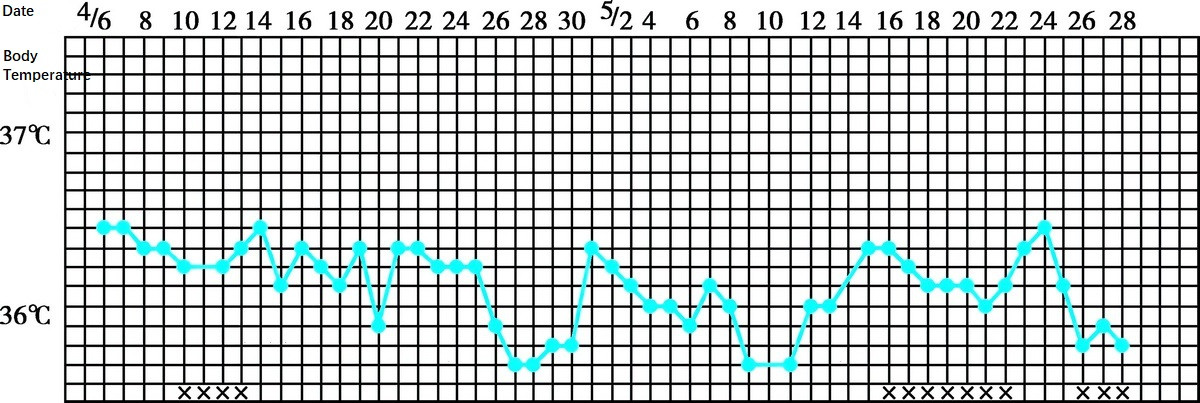

- Basal Body Temperature (BBT): A common and non-invasive tool for diagnosing anovulation. In anovulatory AUB, BBT typically exhibits a monophasic pattern.

- Reproductive Hormone Testing: Evaluates serum progesterone levels 5–9 days before the next expected period (mid-luteal phase equivalent). Progesterone levels below 3 ng/mL suggest anovulation. Additional hormone tests, including LH, FSH, prolactin (PRL), estradiol (E2`), testosterone (T), and thyroid-stimulating hormone (TSH), may identify potential causes of anovulation.

- Diagnostic Curettage: Confirms the pathological diagnosis of the endometrium and has both diagnostic and hemostatic roles. It is indicated for patients with a history of sexual activity, irregular uterine bleeding not responding to medical treatment, high-risk factors for endometrial cancer (e.g., obesity or diabetes), or ultrasound findings of excessive endometrial thickening with heterogeneous echogenicity. Curettage can be performed immediately to control heavy bleeding.

- Hysteroscopy: Enables direct visualization of the cervical canal and endometrium, providing improved diagnostic accuracy through targeted biopsy under direct vision.

Figure 1 Basal body temperature-monophasic pattern (anovulatory abnormal uterine bleeding)

Differential Diagnosis

Systemic Diseases

Conditions such as hematological disorders, liver dysfunction, or thyroid dysfunction (hyperthyroidism or hypothyroidism) can present with abnormal bleeding. Blood tests including complete blood count, liver function tests, and thyroid hormone levels assist in distinguishing these conditions.

Abnormal Pregnancy or Pregnancy Complications

Events such as miscarriage, ectopic pregnancy, gestational trophoblastic diseases, uterine subinvolution, or retained placenta should be considered.

Reproductive Tract Infections

Infections such as acute or chronic vaginitis, cervicitis, endometritis, or myometritis may cause abnormal uterine bleeding.

Reproductive Organ Tumors

Tumors such as endometrial cancer, cervical cancer, ovarian cancer, or fallopian tube cancer need to be ruled out.

Reproductive Tract Injury

Bleeding due to injuries such as vaginal or cervical lacerations requires differentiation.

Use of Hormonal Medications, Anticoagulants, Intrauterine Devices, or Foreign Bodies

Abnormal uterine bleeding can result from the use of exogenous hormones, anticoagulants, intrauterine contraceptive devices, or retained foreign objects.

Other Conditions Causing Abnormal Uterine Bleeding

Conditions such as endometrial polyps, uterine fibroids, adenomyosis, focal endometrial abnormalities, uterine arteriovenous malformations, and uterine scar dehiscence after cesarean section should also be considered.

Treatment

The treatment approach aims to control bleeding promptly, correct anemia, maintain physiological stability, regulate menstrual cycles, and prevent endometrial pathology or recurrence of AUB. In adolescents, treatment primarily focuses on hemostasis and cycle regulation. For women of reproductive age, fertility-preservation treatment, such as ovulation induction, is considered based on individual needs. During the perimenopausal period, it is particularly important to exclude malignancies such as endometrial cancer.

Hemostasis

Hormones

Hormones are the first-line treatment for hemostasis, requiring close monitoring during use to avoid iatrogenic bleeding or other complications.

Progestin-Induced Endometrial Shedding

This method, sometimes referred to as "medical curettage," transforms the hyperplastic endometrium under estrogen stimulation into a secretory phase, which subsequently sheds completely after medication withdrawal. It is suitable for patients with a certain level of endogenous estrogen. Due to the inevitable withdrawal bleeding following discontinuation, this method is not recommended for severe anemia. Examples include:

- Dydrogesterone: 10 mg, orally, twice daily for 10 days.

- Micronized progesterone: 200–300 mg, orally, once daily for 10 days.

- Medroxyprogesterone: 6–10 mg, orally, once daily for 10 days.

For acute AUB, progesterone injection: 20–40 mg intramuscularly once daily for 3–5 days. Withdrawal bleeding typically occurs within 3 days after medication discontinuation and resolves within approximately 1 week.

Progestin-Induced Endometrial Atrophy

High-efficiency synthetic progestins induce endometrial atrophy to achieve hemostasis. For norethisterone, an initial dose of 5 mg every 8 hours can be administered for significant bleeding. Upon bleeding control, the dose is tapered by one-third every three days until a maintenance dose of 2.5–5 mg/day is reached. Treatment extends for 10–21 days or longer until anemia is corrected, with menstrual withdrawal bleeding expected after discontinuation within 3–7 days. Similarly, medroxyprogesterone at 10–30 mg/day can be tapered following the same principles.

Combined Oral Contraceptives (COCs)

COCs are broadly applicable, particularly for adolescents and reproductive-age women. They synchronize the proliferative and shedding endometrium through their estrogen and progestin components, achieving rapid and effective hemostasis. However, they are contraindicated for patients with contraindications to contraceptive use. Commonly used COCs include:

- Ethinylestradiol-cyproterone acetate tablets.

- Drospirenone-ethinylestradiol tablets.

Dosage is typically 1 tablet per dose. For acute AUB, 2–3 doses/day may be administered, while persistent spotting can be managed with 1–2 doses/day. Bleeding typically resolves within 1–3 days. If bleeding persists after 3 days of stable dosing, tapering can begin every 3–7 days by 1 tablet/day until 1 tablet/day is reached. Treatment continues until hemoglobin normalizes.

Estrogen-Induced Endometrial Repair

High-dose estrogen rapidly raises systemic estrogen levels, promoting endometrial growth and repair to achieve short-term hemostasis. This approach is suitable for adolescents with hemoglobin levels below 90 g/L. Due to the large estrogen doses and associated adverse effects, this method is now rarely used clinically.

GnRH Agonists (GnRH-a)

GnRH-a suppresses FSH and LH secretion, lowering estrogen to postmenopausal levels and achieving hemostasis. Immediate bleeding control is not achieved, and GnRH-a is primarily used for refractory AUB. It is particularly suitable for patients with uterine fibroids or adenomyosis accompanied by severe anemia, serving as preparation for subsequent treatment. If GnRH-a therapy exceeds 3 months, add-back therapy is recommended.

Curettage

Curettage provides rapid bleeding control and has diagnostic value. It is indicated for patients with heavy bleeding unresponsive to medical therapy who require immediate hemostasis, those needing histological examination of the endometrium, or those with contraindications to drug therapy. It aids in evaluating endometrial pathology and excluding malignancy. For patients in the perimenopausal period and those of reproductive age with a prolonged course, curettage is often considered as the primary option. In adolescents without a history of sexual activity, curettage is generally avoided unless endometrial cancer needs to be ruled out. Patients who have recently undergone endometrial pathological assessment excluding malignancy or precancerous lesions usually do not require repeated curettage. For uterine cavity lesions identified on ultrasound, hysteroscopic biopsy may enhance diagnostic accuracy.

Adjunctive Therapy

General Hemostatic Drug Treatment

Antifibrinolytic and procoagulant drugs may reduce bleeding as an adjunct to hormone therapy, achieving better hemostatic effects. Antifibrinolytics such as tranexamic acid can be administered via intravenous injection or infusion (0.25–0.5 g per dose, 0.75–2 g per day), or orally (500 mg per dose, three times daily). Other options include ethamsylate, vitamin K, and caffeic acid tablets.

Improvement of Coagulation Function

In cases of severe bleeding, coagulation factors such as fibrinogen, platelets, or fresh frozen plasma may be replenished.

Anemia Correction

For patients with moderate to severe anemia, iron supplements and folic acid should be provided alongside other treatments. Transfusions may be required for severe anemia.

Infection Prevention

In instances of prolonged bleeding, severe anemia, reduced immunity, or clinical signs of infection, antibiotics should be administered promptly.

Cycle Regulation

For AUB-O patients, hemostasis is only the first step in treatment. Further cycle regulation is necessary for all patients and constitutes a crucial part of therapy. Regulating the menstrual cycle helps consolidate treatment efficacy and reduce recurrence risk. Methods of cycle regulation vary based on factors such as age, hormone levels, and the patient's fertility desires.

Progestin in the Luteal Phase

This method is widely applicable for patients of all age groups with a certain level of endogenous estrogen. Natural progestins or dydrogesterone, which have no or minimal inhibitory effects on the hypothalamic-pituitary-ovarian (HPO) axis, are recommended. Treatment can be initiated on the 15th day of withdrawal bleeding, with dydrogesterone taken orally at 10–20 mg/day for 10–14 days, or micronized progesterone at 200–300 mg/day for 10–14 days. Treatment is typically administered over 3–6 cycles as needed.

Combined Oral Contraceptives (COCs)

COCs effectively regulate cycles, making them suitable for patients with heavy menstrual bleeding, dysmenorrhea, acne, hirsutism, or premenstrual syndrome, especially if contraception is also desired. After hemostasis is achieved and withdrawal bleeding occurs, COCs can be taken cyclically for 3 cycles, with adjustments for recurrent issues extending use to 6 cycles. In reproductive-age women with long-term contraceptive needs and no contraindications, COCs may be used longer-term.

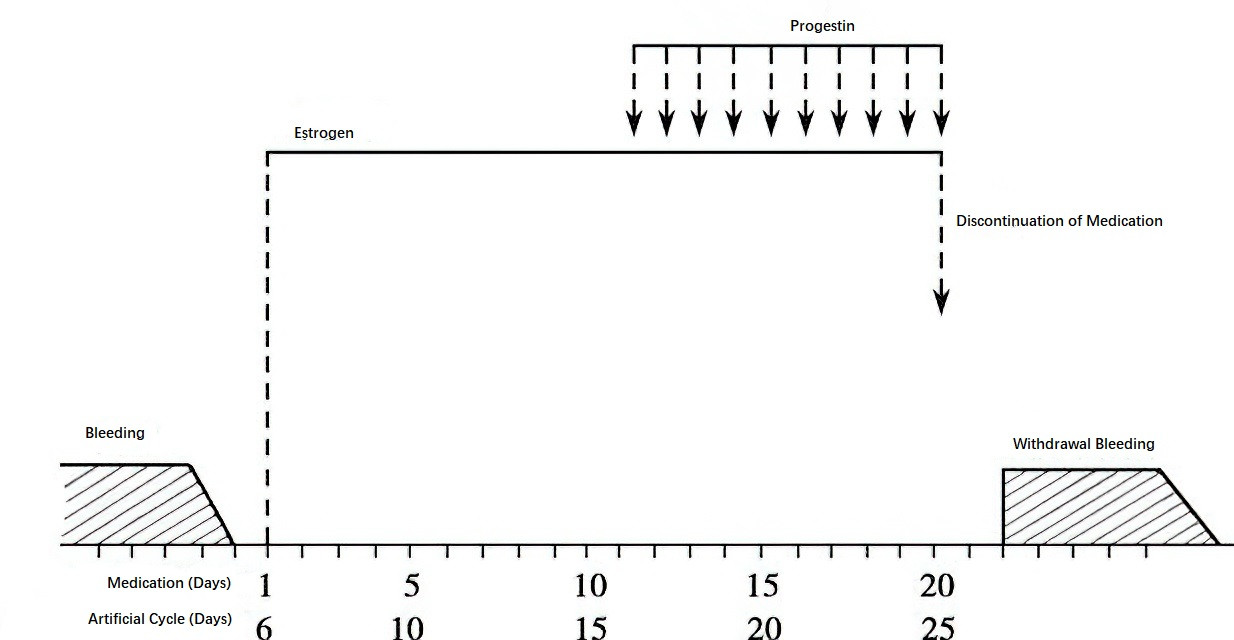

Estrogen-Progestin Sequential Therapy (Artificial Cycle)

This therapy simulates natural ovarian endocrine changes during the menstrual cycle through the sequential cyclic use of estrogen and progestin. It is suitable for certain adolescents or reproductive-age individuals who fail to experience withdrawal bleeding after progestin therapy due to insufficient endogenous estrogen, as well as perimenopausal patients with symptoms of estrogen deficiency.

Figure 2 Diagram of estrogen-progestin sequential therapy

Levonorgestrel-Releasing Intrauterine System (LNG-IUS)

The LNG-IUS releases levonorgestrel locally in the uterine cavity at a rate of 20 μg/day, providing both contraception and endometrial suppression. It offers long-term endometrial protection and significantly reduces bleeding, with minimal systemic side effects. The LNG-IUS is often effective for patients who have failed other medical treatments and do not desire fertility. It is most suitable for reproductive-age or perimenopausal patients with no fertility needs.

Ovulation Induction

Ovulation induction is utilized for reproductive-age women, particularly those desiring pregnancy. Even in cases where pregnancy does not occur, post-ovulatory progesterone production can regulate the menstrual cycle.

Clomiphene Citrate (CC)

Starting on the 5th day of a natural or induced menstrual cycle, 50 mg is taken orally every evening for 5 consecutive days. Ovulation generally occurs within 7–9 days after discontinuation. If ovulation fails, the treatment can be repeated, with doses gradually increasing to 100–150 mg/day over up to 3 cycles.

Letrozole (LE)

Treatment begins on the 2nd–5th day of a natural or withdrawal bleeding cycle, with an initial dose of 2.5 mg/day for 5 days. In cases of anovulation, dosages are increased by 2.5 mg per cycle to a maximum of 5.0–7.5 mg/day. Since letrozole lacks formal approval for ovulation induction, informed consent from the patient is required.

Human Menopausal Gonadotropin (hMG)

Each hMG ampoule contains 75 IU of FSH and LH. Intramuscular injections of 1–2 ampoules per day are initiated on the 5th day of the menstrual cycle and continued until follicular maturation. Once mature, hMG is discontinued, and human chorionic gonadotropin (hCG) at 5,000–10,000 IU is administered via intramuscular injection to increase ovulation rates. This technique, known as the hMG-hCG protocol, carries a risk of ovarian hyperstimulation syndrome (OHSS) and is therefore primarily reserved for patients with poor response to oral ovulation induction drugs, infertility, or those with access to ultrasound monitoring for ovulation.

Human Chorionic Gonadotropin (hCG)

hCG mimics the action of LH to induce ovulation. It is suitable for patients with adequate levels of endogenous FSH and moderate estrogen levels. hCG is usually combined with other ovulation induction drugs, and when ultrasound monitoring indicates nearing follicular maturation, hCG at 5,000–10,000 IU is injected intramuscularly to induce ovulation.

Surgical Treatment

For patients with poor response to medical treatment, contraindications to medications, lack of fertility needs, or difficulty with follow-up—particularly those of older age—surgical treatment may be considered. Cases with pathological diagnoses of precancerous lesions or malignancy are managed according to relevant disease protocols.

Endometrial Ablation

Techniques such as hysteroscopic electrosurgical resection, laser resection, cold-knife resection, rollerball electrocautery, or thermal therapy are used to directly destroy most or all of the endometrium and superficial myometrium, resulting in reduced or absent menstruation. Malignancy or precancerous lesions should be excluded before performing this procedure.

Hysterectomy

If various treatment options fail and all feasible medical approaches have been fully explored, hysterectomy may be chosen with the informed consent of the patient and their family.

Management Options for Anovulatory AUB at Different Life Stages

Adolescence

Hemostasis

Progestin-induced endometrial shedding or combined oral contraceptives (COCs) are commonly used. High-potency synthetic progestin-induced endometrial atrophy with significant side effects is not routinely recommended. Diagnostic curettage and hysteroscopy are also not recommended for routine use because of the low risk of endometrial malignancy at this age.

Cycle Regulation

Natural progestin or dydrogesterone withdrawal therapies, or COCs, are suggested for cycle regulation, with treatment courses of 3–6 months. Estrogen-progestin sequential therapy (artificial cycle) is not routinely recommended.

Reproductive Age

Hemostasis

COCs, progestin-induced endometrial shedding, or progestin-induced endometrial atrophy can be employed. Diagnostic curettage, hysteroscopy, and endometrial biopsy serve as important methods for managing acute AUB and determining whether endometrial lesions are present. However, repeated use of these procedures is discouraged.

Cycle Regulation and Ovulation Induction

For patients with fertility needs, natural progestins or dydrogesterone can be used for withdrawal therapy without affecting pregnancy, combined with ovulation induction treatments, such as clomiphene or letrozole. For those without fertility needs, COCs are recommended for long-term use, or the levonorgestrel-releasing intrauterine system (LNG-IUS) may be considered.

Perimenopause

Hemostasis

Progestin-induced endometrial shedding or progestin-induced endometrial atrophy is recommended. COCs are not advised due to the possible increased risk of thrombosis in perimenopausal patients. Diagnostic curettage, hysteroscopy, and endometrial biopsy are preferred options for first-line hemostasis in patients suspected of endometrial lesions. However, for patients who have recently undergone endometrial biopsy or excluded malignancy, repeated curettage is not necessary.

Cycle Regulation

Progestin Withdrawal Therapy

Natural progestins or dydrogesterone are recommended for periodic withdrawal therapy.

LNG-IUS

This provides long-term, effective protection of the endometrium, significantly reduces menstrual bleeding, and has additional benefits for coexisting conditions such as endometrial polyps, uterine fibroids, adenomyosis, or endometrial hyperplasia.

Hormone Therapy for Estrogen Deficiency Symptoms

For patients with confirmed symptoms of estrogen deficiency and no contraindications to hormone therapy, menopausal hormone therapy may be initiated with natural estrogens combined with progestins or dydrogesterone in sequential regimens (artificial cycles). Regular withdrawal bleeding can help relieve perimenopausal symptoms concurrently.

Prognosis

The prognosis of anovulatory AUB depends on the duration of the condition.

Adolescence

In most cases, normal menstrual cycles are established within three years of menarche. However, patients with a disease course exceeding 4–8 years, such as those with polycystic ovary syndrome (PCOS), may find spontaneous resolution more difficult.

Reproductive Age

Patients with fertility desires typically have a high likelihood of conceiving with ovulation induction therapy. However, many postpartum patients may not resume regular ovulation or may exhibit infrequent ovulation and persistent irregular menstruation, necessitating long-term management.

Perimenopause

The course of disease during this period varies in length and often concludes with menopause. Rarely, malignancy may occur, warranting close attention.