Epithelial ovarian tumors are the most common type of ovarian tumors, accounting for 50% to 70% of all ovarian tumors and 85% to 90% of malignant ovarian tumors. These tumors are predominantly observed in middle-aged and elderly women, while they are rarely seen in prepubescent girls and infants. Traditionally, it has been thought that epithelial ovarian tumors originate from the ovarian surface epithelium, which differentiates in various directions to form serous tumors, mucinous tumors, endometrioid tumors, and clear cell tumors. Current understanding suggests that the histological origins of epithelial ovarian cancers are diverse: high-grade serous carcinoma (HGSC) primarily arises from intraepithelial carcinoma of the fallopian tube, whereas low-grade serous carcinoma (LGSC) develops progressively from benign serous cystadenomas through borderline tumors. Certain studies indicate that ovarian serous cystadenomas originate from fallopian tube fimbrial epithelium implanting on the ovarian surface and forming tubal inclusion cysts. Endometrioid carcinoma and clear cell carcinoma are predominantly thought to arise from the malignant transformation of endometriosis.

Based on histological and biological behavior, epithelial ovarian tumors are categorized as benign, borderline, and malignant. Borderline tumors are characterized microscopically by active epithelial proliferation without significant stromal invasion, with clinical features of slow growth and relatively few instances of recurrence or metastasis. Ovarian carcinomas are marked microscopically by significant cellular atypia and a high mitotic index, with clinical features of rapid progression, difficulty in early diagnosis, complex treatment, and high mortality rates.

Relevant Risk Factors

The etiology of these tumors remains unclear, but several risk factors have been implicated:

Ovulatory Factors

Epidemiological studies suggest that nulliparity and infertility can increase the risk of ovarian cancer, whereas multiple pregnancies, oral contraceptive use, and breastfeeding are associated with a reduced risk.

Genetic Predisposition

Hereditary breast and ovarian cancer syndrome (HBOC), primarily caused by germline mutations in the BRCA1 or BRCA2 genes, is responsible for approximately 20% to 25% of ovarian cancer cases. Women with BRCA1 or BRCA2 germline mutations have lifetime risks of ovarian cancer of 40% to 60% and 11% to 27%, respectively, compared to a lifetime risk of approximately 1.4% in the general population. Lynch syndrome, also known as hereditary nonpolyposis colorectal cancer (HNPCC), is caused by germline mutations in genes such as MLH1, MSH2, MSH6, or PMS2 and is associated with increased risks of ovarian cancer, endometrial cancer, and colorectal cancer. Additionally, germline mutations in other genes, such as BRIP1, PALB2, STK11, RAD51C, RAD51D, and ATM, have been linked to increased ovarian cancer risk.

Endometriosis

Morphological and molecular evidence suggests that ovarian endometrioid carcinoma and clear cell carcinoma largely originate from the malignant transformation of endometriosis.

Based on clinical, pathological, and molecular genetic characteristics, epithelial ovarian cancers are classified into two broad categories: Type I and Type II.

Type I Tumors grow slowly and often have precursor lesions, typically presenting in early clinical stages with relatively favorable prognoses. They include histological subtypes such as low-grade serous carcinoma, low-grade endometrioid carcinoma, mucinous carcinoma, and clear cell carcinoma. These tumors are characterized by molecular genetic alterations such as KRAS, BRAF, PIK3CA, ERBB2, CTNNB1, and PTEN mutations, as well as high-frequency microsatellite instability.

Type II Tumors progress rapidly, lack identifiable precursor lesions, exhibit aggressive behavior, and are often diagnosed at advanced clinical stages with poor prognoses. Histological subtypes include high-grade serous carcinoma, high-grade endometrioid carcinoma, undifferentiated carcinoma, and carcinosarcoma. These tumors are predominantly associated with molecular changes such as TP53 mutations and alterations in BRCA genes.

Pathology

Epithelial ovarian tumors are categorized into the following histological types:

Serous Tumors

Serous Cystadenoma

Serous cystadenoma accounts for 25% of benign ovarian tumors. It is typically unilateral, with a variable size, a smooth surface, and cystic nature. The tumor is usually unilocular, with a thin wall and filled with clear fluid. Microscopically, the cyst wall is fibrous and lined with a single layer of tubal-type cuboidal or columnar epithelium, often with cilia, and demonstrates no significant atypia.

Serous Borderline Tumor

Approximately one-third of serous borderline tumors are bilateral. They are typically cystic, often exceeding 5 cm in diameter. They may exhibit papillary growth within the cyst wall or on the ovarian surface. Microscopically, the tumor shows progressively branching papillae lined with pseudo-stratified or stratified serous epithelium. Nuclear atypia ranges from mild to moderate, and mitotic figures are rare. The prognosis is favorable.

In the 2020 WHO Histological Classification of Tumors of the Female Reproductive System, a micropapillary subtype of serous borderline tumor is distinctly recognized. The diagnostic criterion for this subtype is the presence of fused micropapillary structures ≥5 mm in size. These slender micropapillae are typically at least five times taller than their width, with little or no stromal core, and the nuclei exhibit more pronounced atypia. Microinvasion in serous borderline tumors is defined as clusters of epithelial cells with eosinophilic cytoplasm in the stroma, <5 mm across, with morphology similar to non-invasive components. If the morphology resembles low-grade serous carcinoma but invasion is <5 mm, it is designated as microinvasive carcinoma, and extensive sampling is required to rule out a larger invasive carcinoma.

Serous Carcinoma

Serous carcinoma constitutes 75% of ovarian cancers and is divided into high-grade serous carcinoma (HGSC) and low-grade serous carcinoma (LGSC). High-grade serous carcinoma accounts for 90%–95% of all serous carcinomas, is often bilateral, relatively large, and displays exophytic, cystic-solid, or solid morphology. The solid areas typically appear grayish-white with extensive necrosis and hemorrhage. Microscopically, HGSC commonly exhibits solid, papillary, glandular, or cribriform patterns with large, hyperchromatic, pleomorphic nuclei, active mitosis (>12 mitoses/10 HPF), frequent necrosis, and multinucleated tumor giant cells. The prognosis is poor.

Low-grade serous carcinoma, comprising 5%–10% of serous carcinomas, is frequently bilateral, cystic-solid, and is characterized by delicate papillary structures. Microscopically, growth patterns include papillary, micropapillary, or nested arrangements. Nuclear atypia is mild to moderate, mitotic figures are less frequent (3–5 mitoses/10 HPF), psammoma bodies are commonly observed, and necrosis is rare. Survival outcomes are significantly better than those for HGSC.

Mucinous Tumors

Mucinous Cystadenoma

Mucinous cystadenoma accounts for 20% of benign ovarian tumors and 80% of all mucinous tumors. These tumors are almost always unilateral, round or ovoid, and often large or even massive. They have a smooth exterior surface and appear grayish-white. On sectioning, the tumor is typically multilocular, filled with gelatinous mucus, and rarely features papillary growth. Microscopically, the cyst wall is fibrous and lined with a single layer of mucinous columnar epithelium, often containing goblet cells.

Mucinous Borderline Tumor

These tumors are almost exclusively unilateral, quite large (commonly >10 cm in diameter), with a smooth surface. They are multilocular on sectioning, with thickened walls that may contain small, soft papillary growths. Microscopically, the tumor epithelium consists of gastrointestinal-type mucinous cells arranged in multilayers with mild to moderate atypia. Cellular clusters, villous, or flimsy papillary structures may be present. Proliferative areas must account for more than 10% of the epithelial content for a diagnosis, or the tumor remains classified as mucinous cystadenoma with focal epithelial proliferation.

Mucinous Carcinoma

Most mucinous carcinomas are metastatic, with primary ovarian mucinous carcinoma being uncommon and representing 3%–4% of ovarian cancers. These tumors are large, unilateral, and may be solid or cystic-solid, with smooth surfaces. They often contain mucin and may exhibit areas of hemorrhage and necrosis. Microscopically, benign, borderline, and malignant components usually coexist within a single tumor, displaying a continuum of tissue structure and cytological features. Two distinct invasion patterns are recognized: expansive invasion, characterized by closely packed glands or labyrinth-like structures with minimal or absent stroma, and destructive invasion, marked by irregular glands, cellular nests, or single cells infiltrating the stroma. Malignant mucinous tumors with invasive growth, especially those involving both ovaries, should prompt investigation for a metastatic origin.

Endometrioid Tumors

Benign tumors are rare and usually unilocular with smooth surfaces. Their cyst walls are lined with columnar epithelium resembling normal endometrial glands, with hemosiderin-laden macrophages occasionally present in the stroma. Borderline endometrioid tumors are also uncommon, typically unilateral and relatively large, with smooth surfaces. Microscopically, they exhibit densely packed glands of variable sizes with irregular contours, resembling atypical endometrial hyperplasia. Nuclear atypia is mild to moderate, and mitotic activity is generally low. Endometrioid carcinoma accounts for roughly 10% of ovarian cancers and primarily arises from endometriosis. These tumors are generally unilateral, relatively large (average diameter 11 cm), solid or cystic-solid, with papillary growths, and cyst cavities often filled with hemorrhagic fluid. Microscopically, they closely resemble endometrial carcinoma, commonly appearing as well-differentiated adenocarcinomas with squamous differentiation.

Clear Cell Tumors

Benign clear cell tumors are rare, and borderline clear cell tumors are frequently associated with clear cell carcinoma. Clear cell carcinoma accounts for 10%–12% of ovarian cancers, with a higher prevalence in Asians. In Japanese populations, its incidence is as high as 20%–30%. Between 50% and 74% of clear cell carcinomas arise from endometriosis. These tumors are generally unilateral and large, with solid, cystic-solid, or cystic compositions. Microscopically, they exhibit tubular-cystic, papillary, and solid structures, often coexisting. Tumor cells display abundant clear cytoplasm, pronounced nuclear atypia, hyperchromasia, and the characteristic hobnail cells lining tubular or cystic structures. Clear cell carcinoma shows poor sensitivity to chemotherapy and has an overall poor prognosis.

Brenner Tumors

Most Brenner tumors are benign, accounting for 5% of benign ovarian epithelial tumors. They are usually unilateral, small, smooth-surfaced, solid, and firm, with a grayish-white whorled or woven appearance on sectioning. Microscopically, the hallmark feature is nests of oval or irregular transitional-like epithelial cells within a dense fibrous stroma. The epithelial nests may form central lumens containing mucus or eosinophilic material. Borderline and malignant Brenner tumors also occur, though they are less common.

Treatment

Benign Ovarian Epithelial Tumors

Once a diagnosis of ovarian tumor is confirmed, surgical treatment is generally adopted. The extent of surgery is determined based on the patient’s age, fertility requirements, and the condition of the contralateral ovary. For young patients with unilateral tumors, ovarian tumor resection or unilateral adnexectomy is performed. For bilateral tumors, tumor resection is recommended, with efforts to preserve as much normal ovarian tissue as possible. Patients who are perimenopausal or postmenopausal and have a normal contralateral ovary may undergo unilateral adnexectomy or hysterectomy with bilateral adnexectomy. Tumor dissection is recommended during surgery, with frozen-section histopathological analysis conducted when necessary. Preventing tumor rupture during surgery is critical to avoid implantation of tumor cells in the peritoneal cavity. For large benign cystic tumors, aspiration can be performed to reduce tumor size for removal, although care should be taken to protect surrounding tissues from contamination by cyst fluid prior to puncture. Aspiration should be conducted slowly to prevent a sudden drop in intra-abdominal pressure, which could lead to shock.

Borderline Ovarian Epithelial Tumors

Surgery represents the primary treatment for borderline ovarian epithelial tumors, with the primary objective being complete tumor removal, typically through adnexectomy. Staging surgery is generally recommended for these tumors, though the necessity of retroperitoneal lymphadenectomy remains a subject of debate. While retroperitoneal lymphadenectomy can provide precise tumor staging, it has not been shown to improve survival outcomes. Meanwhile, omentectomy and multiple peritoneal biopsies have been shown to improve staging accuracy in up to 30% of patients. Adjuvant chemotherapy is generally not recommended post-surgery, except in cases involving invasive implants, which are treated following regimens similar to those for low-grade epithelial carcinomas.

Malignant Ovarian Epithelial Tumors (Ovarian Cancer)

The principal treatment strategy for ovarian cancer involves both surgery and chemotherapy, which are considered equally important. Targeted therapies, such as anti-angiogenic agents and poly ADP-ribose polymerase (PARP) inhibitors, may also complement these treatments. Ovarian cancer is approached as a chronic disease, with an emphasis on continuous management throughout the course of the disease.

Surgical Treatment

Surgery is the cornerstone of ovarian cancer treatment. The extent of surgery is determined by intraoperative findings and results from frozen-section pathology. The completeness of the initial surgery is closely associated with prognosis.

- Early-stage disease (FIGO stage I): Comprehensive staging surgery is performed, including cytological examination of ascitic fluid or peritoneal washings; detailed exploration of the pelvic and abdominal cavities with multiple tissue biopsies from suspected or metastasis-prone sites; total hysterectomy with bilateral salpingo-oophorectomy to ensure complete tumor resection; omentectomy; pelvic lymphadenectomy (covering common iliac, internal iliac, external iliac, and obturator lymph nodes); and para-aortic lymphadenectomy to the level of the renal vessels. For young, early-stage, low-risk patients desiring fertility preservation, the uterus can be retained, and unilateral salpingo-oophorectomy (for stage IA) or bilateral salpingo-oophorectomy (for stage IB) can be performed as part of comprehensive staging surgery. Fertility-preserving surgeries are non-standard and carry certain risks, so patients and/or their families should provide fully informed consent.

- Advanced-stage disease (FIGO stages II–IV): Cytoreductive surgery, also referred to as debulking surgery, is performed. The goal is to remove as much of the primary and metastatic tumors as possible, minimizing residual disease. When necessary, resection of organs such as the bowel, bladder, or spleen may be required. Suspicious and/or enlarged lymph nodes detected on preoperative imaging or during surgery should be removed if feasible, while clinically negative lymph nodes do not require removal. Surgery is considered optimal (optimal debulking) when the largest diameter of residual disease is <1 cm, with the ultimate objective being no visible residual disease (R0). For stage III or IV patients for whom optimal cytoreduction is unlikely, neoadjuvant chemotherapy may be administered to reduce tumor burden, followed by interval debulking surgery. R0 achievement after surgery provides the greatest benefit to patients.

For recurrent ovarian cancer, secondary cytoreductive surgery may be considered for patients meeting certain criteria: relapse-free intervals exceeding six months (platinum-sensitive), localized lesions that can be completely resected, and little to no ascites. Patients achieving R0 in the second surgery significantly benefit from this approach.

Chemotherapy

Chemotherapy is highly effective for the majority of epithelial ovarian carcinomas, even in cases of extensive metastasis. Chemotherapy can involve postoperative adjuvant chemotherapy (first-line therapy), neoadjuvant chemotherapy (preoperative), and salvage chemotherapy (second-line or later) for recurrent disease. Most patients, apart from those with early-stage, low-risk epithelial carcinomas (e.g., stage IA or IB mucinous carcinoma, low-grade serous carcinoma, or low-grade endometrioid carcinoma), require chemotherapy.

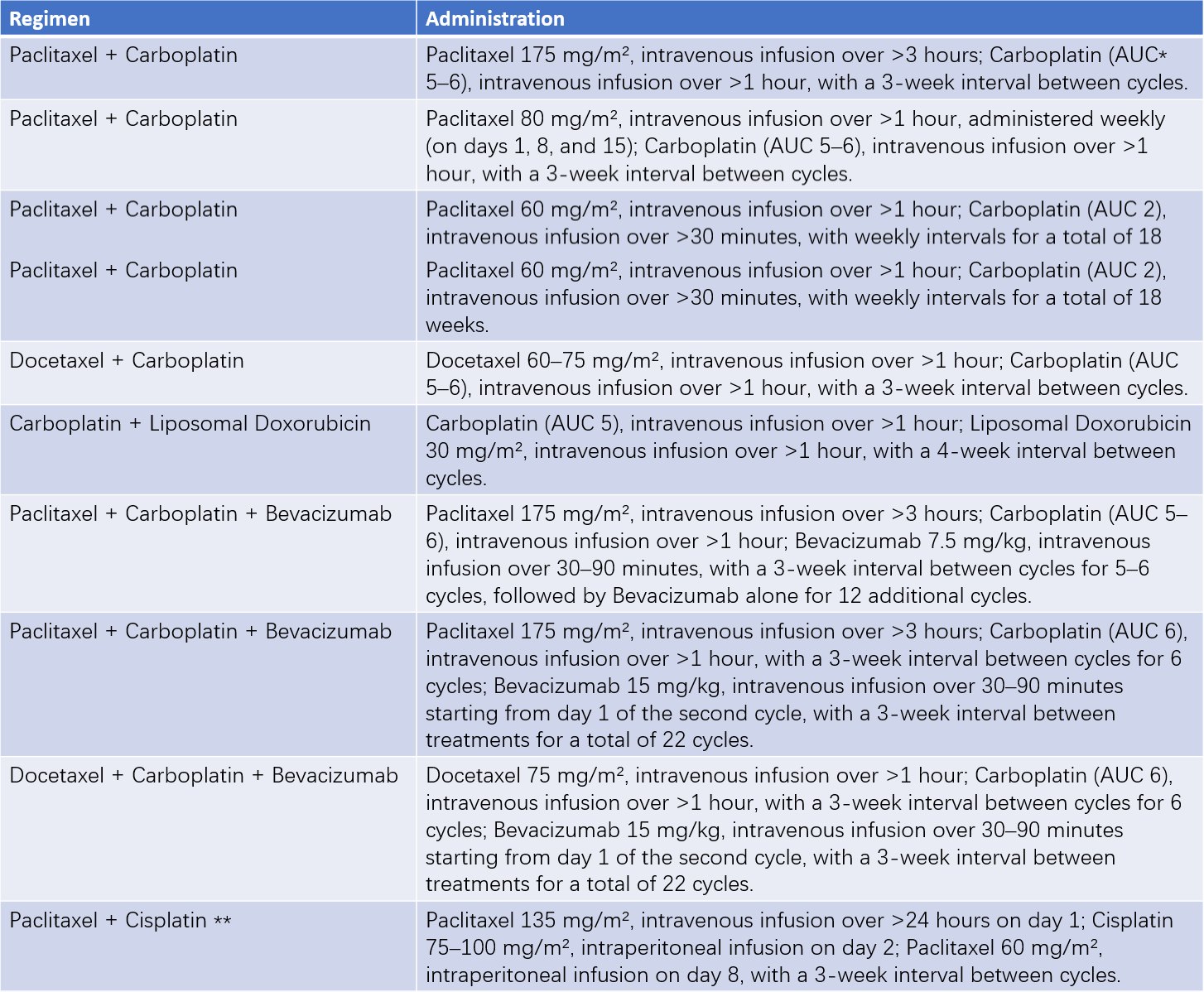

Table 1 Common chemotherapy regimens for epithelial ovarian cancer

Note:

*AUC (area under the curve) indicates the carboplatin dose, calculated based on the patient’s creatinine clearance and desired AUC value.

**Intravenous and intraperitoneal chemotherapy regimens are suitable for patients with stages II–III disease who achieve optimal cytoreductive surgery.

Common chemotherapeutic agents include cisplatin, carboplatin, paclitaxel, docetaxel, liposomal doxorubicin, and gemcitabine. Postoperative adjuvant chemotherapy typically involves platinum-based combination regimens, with carboplatin plus paclitaxel as the preferred first-line choice. For early-stage high-grade serous carcinoma, six cycles of chemotherapy are generally recommended, while three cycles may suffice for other histological subtypes. Late-stage ovarian cancer typically requires six cycles of chemotherapy. For patients with primary ovarian mucinous carcinoma, regimens such as fluorouracil + leucovorin + oxaliplatin or capecitabine + oxaliplatin may also be considered in combination.

Intravenous chemotherapy remains the standard strategy for ovarian cancer, although intraperitoneal chemotherapy combined with systemic treatment may benefit patients who achieve optimal cytoreduction in the initial surgery. Neoadjuvant chemotherapy regimens are similar to postoperative ones and typically involve 3–4 cycles administered intravenously. Its purpose is to shrink the tumor and allow for optimal cytoreduction during interval debulking surgery. For patients achieving optimal debulking after neoadjuvant chemotherapy, hyperthermic intraperitoneal chemotherapy can offer significant benefits.

Salvage chemotherapy for recurrent disease should account for the regimen, efficacy, side effects of prior treatments, and the timing of recurrence. Primary considerations include:

- For patients who have not previously undergone platinum-based chemotherapy, platinum-based combination therapy is preferred.

- For patients previously treated with platinum-based chemotherapy, platinum-based regimens should be considered for platinum-sensitive relapse (time to recurrence ≥6 months after treatment). For platinum-resistant relapse (recurrence within <6 months) or refractory cases, non-platinum-based regimens are generally used.

Targeted Therapy

Anti-angiogenic drugs and PARP inhibitors have emerged as new clinically practical antitumor agents. Anti-angiogenic drugs suppress tumor growth by inhibiting angiogenesis. Bevacizumab has shown significant efficacy in the initial treatment and maintenance therapy for patients with advanced epithelial ovarian cancer following surgery, as well as in the treatment of recurrent ovarian cancer. Bevacizumab administration has been associated with significantly prolonged progression-free survival, and in some patients, extended overall survival has also been observed.

PARP inhibitors, such as olaparib, niraparib, fluzoparib, and pamiparib, have been approved for clinical use. Numerous randomized controlled trials have demonstrated that after achieving remission from initial treatment or platinum-sensitive relapse treatment of ovarian cancer, maintenance therapy with PARP inhibitors can significantly prolong progression-free survival and even overall survival. This effect is particularly pronounced in patients with BRCA gene mutations or homologous recombination repair deficiency (HRD). PARP inhibitors have reshaped the approach to ovarian cancer treatment and have established maintenance therapy as a critical component of comprehensive ovarian cancer management.

Additionally, the MEK inhibitor trametinib has demonstrated favorable efficacy in treating recurrent low-grade serous carcinoma.

Endocrine Therapy

Endocrine therapy is primarily utilized for the management of low-grade serous carcinoma and low-grade endometrioid carcinoma. Frequently used agents include aromatase inhibitors (anastrozole, letrozole), GnRH agonists (leuprorelin acetate), medroxyprogesterone acetate, tamoxifen, and fulvestrant.

Immunotherapy

The efficacy of immune checkpoint inhibitors in treating ovarian cancer is limited. Currently, immune checkpoint inhibitors such as pembrolizumab are recommended only as subsequent-line treatment for patients with recurrent ovarian cancer who exhibit MSI-H (microsatellite instability-high), dMMR (deficient mismatch repair), or TMB-H (tumor mutational burden ≥ 10 mutations per megabase).

Radiation Therapy

The therapeutic value of radiation therapy in ovarian cancer is limited. It may be selectively used as a subsequent-line treatment for isolated, drug-resistant recurrent epithelial ovarian cancer.