Ovarian tumors exhibit the greatest diversity in histological types, with significant differences in biological behavior, clinical manifestations, and prognosis among various types.

Histological Classification

Ovarian tumors can be broadly divided into four categories: epithelial tumors, germ cell tumors, sex cord-stromal tumors, and metastatic tumors.

Epithelial Tumors

Epithelial tumors are the most common histological type, accounting for 50%–70% of ovarian tumors. These tumors are further classified as serous, mucinous, endometrioid, clear cell, seromucinous, and Brenner tumors. Based on histological features and biological behavior, these are subdivided into benign, borderline, and malignant tumors.

Germ Cell Tumors

Germ cell tumors arise from germ cells and represent 20%–40% of ovarian tumors. These include teratomas, dysgerminomas, yolk sac tumors, embryonal carcinomas, non-gestational choriocarcinomas, and mixed germ cell tumors.

Sex Cord-Stromal Tumors

These tumors originate from sex cords and mesenchymal tissues in the primitive gonads and account for 5%–8% of ovarian tumors. They are classified as sex cord tumors, stromal tumors, or mixed sex cord-stromal tumors.

Metastatic Tumors

Metastatic tumors are secondary tumors that result from metastasis of primary malignancies from other organs, such as the gastrointestinal tract, reproductive tract, or breast, to the ovary. According to the 2020 WHO Classification of Female Genital Tumors, ovarian tumors are categorized into: serous tumors, mucinous tumors, endometrioid tumors, clear cell tumors, seromucinous tumors, Brenner tumors, other types of epithelial tumors, mesenchymal tumors, mixed epithelial and mesenchymal tumors, sex cord-stromal tumors, germ cell tumors, miscellaneous tumors, mesotheliomas, tumor-like lesions, and metastatic tumors.

Metastatic Pathways of Malignant Tumors

Intraperitoneal implantation and lymphatic spread are the primary metastatic pathways of malignant ovarian tumors. The metastases often involve extensive pelvic and abdominal cavity dissemination, including the diaphragm, omentum, surfaces of pelvic-abdominal organs, parietal peritoneum, and retroperitoneal lymph nodes. Even tumors that appear confined to the ovary at the primary site are capable of widespread metastasis, with epithelial carcinomas being particularly characteristic in this regard.

Lymphatic metastasis occurs via three routes:

- Ascending spread from the ovarian lymphatics along the ovarian blood vessels to para-aortic lymph nodes.

- Involvement of the internal and external iliac lymph nodes through the ovarian hilum lymphatics, extending to common iliac lymph nodes and subsequently to para-aortic lymph nodes.

- Spread to the inguinal and external iliac lymph nodes via the round ligament of the uterus.

The diaphragm, especially the right subdiaphragmatic lymphatic plexus, is a frequent site of metastasis due to its susceptibility to invasion. Hematogenous metastasis is rare but may occur in advanced stages, spreading to the lungs, liver, brain, bones, and other organs.

Staging

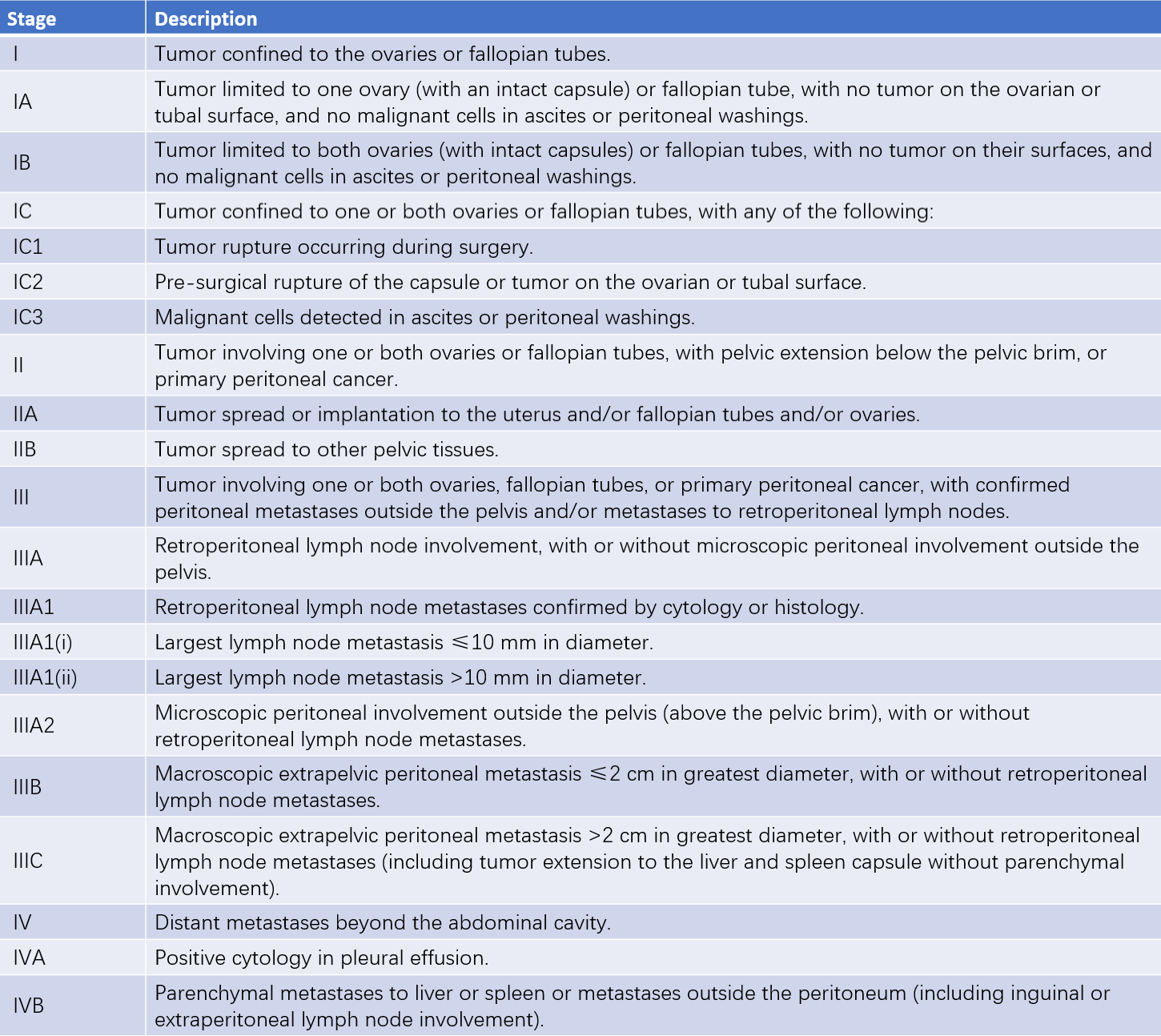

The FIGO 2014 staging system, which is based on surgical and pathological findings, is used for ovarian cancer, fallopian tube cancer, and primary peritoneal cancer.

Table 1 Staging of ovarian, fallopian tube, and primary peritoneal cancer (FIGO 2014)

Clinical Manifestations

Benign Tumors

Small benign tumors are often asymptomatic and are typically discovered incidentally during gynecological examinations. As the tumor enlarges, symptoms such as abdominal distension or the presence of an abdominal mass may arise. Tumors that grow to fill the pelvic and abdominal cavities may cause compression symptoms, including frequent urination, constipation, shortness of breath, or palpitations. Physical examination may reveal abdominal distension with dull percussion sounds, but no shifting dullness. Bimanual or combined recto-abdominal-vaginal examination can detect a smooth, mobile, well-circumscribed mass on one or both sides of the uterus, not adherent to the uterus.

Malignant Tumors

Early-stage malignant tumors are usually asymptomatic. In advanced stages, patients often present with non-specific symptoms such as abdominal distension, poor appetite, or vague abdominal pain. Some patients may exhibit cachexia, weight loss, or anemia. Functional tumors may cause abnormal vaginal bleeding. Gynecological examination often reveals pelvic or abdominal masses, which may be bilateral, solid or complex, with irregular surfaces and limited mobility, often associated with pelvic or abdominal effusion. Combined recto-abdominal-vaginal examination may detect hard nodules or masses in the rectouterine pouch. Enlarged lymph nodes in the inguinal or supraclavicular regions or upper abdominal masses may sometimes also be palpable.

Complications

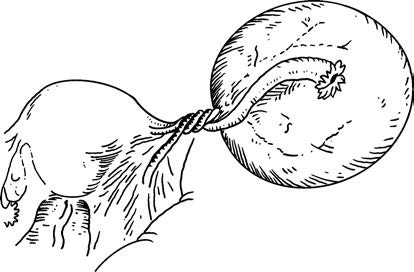

Torsion of the Pedicle

Torsion of the ovarian tumor pedicle is a common gynecological emergency, occurring in approximately 10% of ovarian tumors. It is more frequent in tumors with long pedicles, moderate size, good mobility, and a weight center that leans to one side, such as mature teratomas. Pedicle torsion often occurs after sudden changes in body position or during pregnancy and the puerperium when uterine size and position change. The pedicle involved in ovarian tumor torsion includes the infundibulopelvic ligament, the ovarian ligament, and the fallopian tube. Acute torsion obstructs venous return, leading to tumor congestion, rupture of blood vessels, and intratumoral hemorrhage, causing rapid tumor enlargement. When arterial blood flow is compromised, ischemic necrosis, rupture, and secondary infection may occur. A typical symptom of torsion is the sudden onset of severe unilateral lower abdominal pain following a positional change, often accompanied by nausea, vomiting, or even shock. On bimanual examination, a tender mass is often palpable, with the most intense tenderness at the pedicle. In some cases, incomplete torsion may resolve naturally, alleviating abdominal pain. Treatment involves emergency surgery once a diagnosis is made.

Figure 1 Ovarian tumor pedicle torsion

Rupture

Approximately 3% of ovarian tumors can rupture, classified as spontaneous or traumatic. Spontaneous rupture often results from rapid, invasive tumor growth that breaks through the cyst wall. Traumatic rupture can occur due to severe abdominal trauma, childbirth, sexual intercourse, pelvic examination, or puncture. The severity of symptoms depends on the size of the rupture site and the amount and nature of fluid that enters the abdominal cavity. Rupture of small cysts or simple serous cystadenomas usually causes mild abdominal pain, while rupture of large cysts or teratomas often leads to severe abdominal pain accompanied by nausea and vomiting. Rupture can result in intraperitoneal hemorrhage, peritonitis, and shock. Signs include abdominal tenderness, muscle rigidity, evidence of ascites, and in some cases, a reduction or disappearance of the original pelvic mass. A diagnosis of tumor rupture warrants immediate surgery, including aspiration of cyst fluid, thorough cleaning of the pelvic and abdominal cavities, and submission of surgical specimens for histopathological examination.

Infection

Infection of ovarian tumors is rare and often secondary to torsion or rupture. It can also spread from infection in nearby organs, such as an appendiceal abscess. Symptoms include fever, abdominal pain, abdominal tenderness with rebound pain, abdominal muscle rigidity, abdominal mass, and leukocytosis. Treatment involves surgical removal of the tumor after infection control. Severe infections require prompt surgical excision of the lesion.

Malignant Transformation

Rapid tumor growth, especially in bilateral tumors, indicates a possible malignancy that necessitates early surgical intervention.

Diagnosis

The diagnostic process requires considering the patient’s age, medical history, and physical examination findings, supplemented by necessary tests to preliminarily determine the following:

- Whether the mass originates from the ovary.

- Whether the mass is a tumor.

- Whether the tumor is benign or malignant.

- The possible histological type of the tumor.

- The extent of metastasis in cases of malignancy.

A definitive diagnosis of an ovarian tumor relies on histopathological examination. Common auxiliary diagnostic methods include the following:

Imaging Studies

Ultrasound

Ultrasound imaging reveals the location, size, shape, cystic or solid components, and internal structures, such as papillary projections, providing clues about the nature of the tumor. The diagnostic accuracy is approximately 90%. Color Doppler ultrasound can assess blood flow changes in the mass, aiding diagnosis.

X-ray of the Chest and Abdomen

Chest X-rays help identify pleural effusion and lung metastases, while abdominal X-rays can indicate bowel obstruction. In the case of ovarian teratomas, X-rays can show teeth, bones, or calcified cyst walls.

Computed Tomography (CT)

CT scans provide clear visualization of the tumor shape, evaluate surrounding invasion, and assess lymph node involvement and distant metastases.

Magnetic Resonance Imaging (MRI)

MRI has high soft tissue resolution and is effective in characterizing tumor properties and their relationships with adjacent organs, aiding in lesion localization and mapping structural relationships.

Positron Emission Tomography-Computed Tomography (PET/CT)

PET/CT is not typically used for initial diagnosis but is effective for identifying and localizing recurrent ovarian cancer.

Tumor Markers

These include:

- Serum CA125: Elevated in 80% of epithelial ovarian cancer cases, though it is not elevated in nearly half of early-stage cases. CA125 is primarily used for monitoring disease progression and evaluating treatment efficacy rather than for early diagnosis.

- Serum HE4: Often combined with CA125 for early detection, differential diagnosis, treatment monitoring, and prognosis assessment of ovarian cancer.

- Serum CA199 and CEA: Levels may increase in epithelial ovarian cancers, especially mucinous ovarian carcinoma, which has diagnostic significance.

- Serum AFP: Specific for yolk sac tumors and is elevated in immature teratomas, mixed dysgerminomas, or embryonal carcinomas with yolk sac components.

- Serum hCG: Specific for non-gestational choriocarcinoma.

- Sex Hormones: Ovarian granulosa cell tumors and thecomas may secrete estrogen, while Sertoli-Leydig cell tumors may produce androgens. Serous, mucinous cystadenomas, and Brenner tumors may occasionally secrete small amounts of estrogen.

Laparoscopic Examination

Direct observation of the tumor's external appearance and the pelvic, abdominal, and diaphragmatic regions is possible. Suspicious areas may undergo multiple biopsies, and peritoneal fluid can be collected for cytological examination. Laparoscopy can also be used to assess the feasibility of surgery.

Cytological Examination

Cytological evaluation of ascites, peritoneal lavage fluid, or pleural effusion provides critical insights into the nature of the lesion, aids staging, and informs the choice of treatment strategy.

Differential Diagnosis

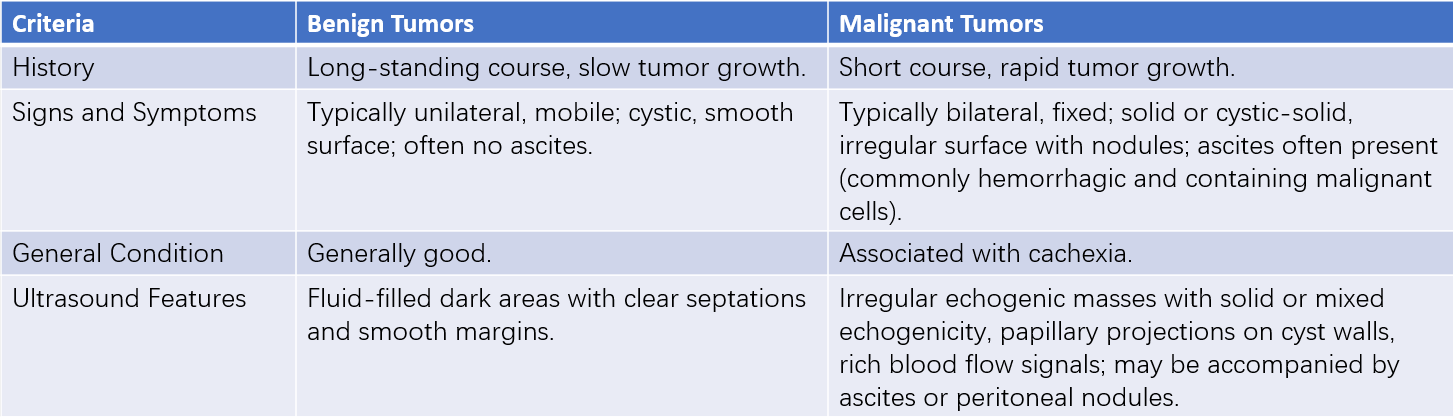

Differentiation Between Benign and Malignant Tumors

Table 2 Differentiation between benign and malignant tumors

Differential Diagnosis of Benign Tumors

Ovarian Tumor-Like Lesions

The most common are follicular cysts and corpus luteum cysts, which are usually unilateral, thin-walled, and typically <5 cm in diameter. These cysts often resolve spontaneously after 2–3 months. If the mass persists or enlarges, the likelihood of an ovarian tumor increases.

Tubal or Ovarian Cysts

These are inflammatory fluid collections, often occurring in patients with a history of pelvic inflammatory disease. Irregular, tubular cystic masses can be observed in the adnexal regions bilaterally, with clear boundaries but limited mobility.

Uterine Fibroids

Subserosal fibroids or fibroids with cystic degeneration can resemble ovarian tumors. Fibroids are often multiple and connected to the uterus, moving in conjunction with the uterine body and cervix during examination. Ultrasonography can assist in differentiation.

Pregnant Uterus

In early pregnancy, the uterus enlarges and softens, and during bimanual examination, the uterine isthmus is extremely soft, making the uterus appear disconnected from the cervix, potentially leading to confusion with an ovarian tumor. Pregnant women often have a history of amenorrhea, and hCG testing or ultrasonography confirms the diagnosis.

Ascites

Patients with ascites often have a history of liver, cardiac, or renal disease. On physical examination, both sides of the abdomen bulge into a "frog belly" appearance in the supine position. Percussion reveals tympanic sounds in the middle of the abdomen and dullness on both sides, with positive shifting dullness. Ultrasonography shows irregular fluid-filled dark areas without space-occupying lesions, with a fluid level that changes with body position and floating intestinal loops visible. In contrast, a large ovarian cyst results in a mid-abdominal bulge in the supine position with dullness on percussion, tympanic sounds on both sides, negative shifting dullness, and a clearly defined boundary. Ultrasonography shows a spherical fluid-filled dark area with smooth and regular edges, and the fluid level does not change with position. Malignant ovarian tumors are often associated with ascites.

Differential Diagnosis of Malignant Tumors

Endometriosis

Endometriosis can present with adhesive masses and nodules in the rectouterine pouch, sometimes with elevated CA125, thus mimicking malignant tumors. However, endometriosis is typically associated with progressive dysmenorrhea, menstrual irregularities, and other symptoms. Ultrasonography and laparoscopy can help distinguish between the two conditions.

Tuberculous Peritonitis

This condition often involves elevated CA125, ascites, and adhesive masses in the pelvis and abdomen, potentially mimicking malignancy. However, tuberculous peritonitis is typically seen in younger, infertile women and is associated with a history of pulmonary tuberculosis, oligomenorrhea or amenorrhea, low-grade fever, and night sweats. In gynecological examination, pelvic masses are higher in position, irregularly shaped, poorly defined, and immobile. The percussion sounds between tympany and dullness may lack clarity. Imaging, tuberculin skin tests, or biopsy during laparotomy or laparoscopy can confirm the diagnosis through histopathological examination if needed.

Extragential Tumors

Differentiation is necessary from retroperitoneal tumors, rectal cancer, or sigmoid colon cancer. Retroperitoneal tumors are fixed and may displace the uterus, rectum, or ureters when located low in the pelvis. Rectal and sigmoid cancers are often associated with gastrointestinal symptoms. Imaging studies and colonoscopy can aid in differentiation.

Treatment

Ovarian tumors require surgical treatment upon detection. The purposes of surgery include:

- Clarifying the diagnosis.

- Removing the tumor.

- Performing surgical pathological staging for malignant tumors.

- Relieving complications.

During surgery, the tumor is dissected for rapid frozen-section histopathological examination to confirm the diagnosis. Surgery can be performed via laparoscopy or laparotomy. Benign tumors are generally managed with laparoscopic surgery, while malignant tumors usually require open surgery. For selected early-stage cases, comprehensive staging surgery may also be performed laparoscopically. Postoperative adjuvant treatment for malignant tumors depends on factors such as histological type, grade, pathological stage, and the size of residual lesions. Chemotherapy is the primary adjuvant therapy and is as important as surgery.

Prognosis of Malignant Tumors

The prognosis of malignant ovarian tumors is influenced by factors such as tumor stage, pathological type, histological grade, and the size of residual lesions. Tumor stage and the size of residual lesions after primary surgery are the most significant prognostic factors. Earlier stages and smaller residual lesions predict better outcomes.

Follow-Up and Monitoring for Malignant Tumors

Malignant tumors have a high recurrence risk, necessitating long-term follow-up and monitoring. Typically, follow-up occurs every three months during the first two years after treatment, every four to six months between three to five years, and annually after five years. Follow-up assessments include medical history review, physical examination, tumor marker testing, and imaging studies. Tumor markers such as serum CA125, AFP, or hCG are chosen based on the preoperative tumor profile. Ultrasound is the preferred imaging modality, with CT, MRI, or PET/CT recommended for further evaluation if abnormalities are detected.

Prevention

Screening

Current evidence suggests routine screening in the general population does not reduce ovarian cancer mortality. However, CA125 combined with transvaginal ultrasound may improve early diagnosis in high-risk populations.

Genetic Testing and Genetic Counseling

Genetic testing and counseling are recommended for individuals at high risk. Genetic testing for hereditary ovarian cancer is applicable to patients with epithelial ovarian cancer, fallopian tube cancer, or peritoneal cancer, as well as their first- or second-degree relatives. It also applies to individuals with known relatives carrying pathogenic or likely pathogenic mutations associated with cancer susceptibility. Risk prediction models suggesting a >5% probability of carrying BRCA1/BRCA2 mutations also qualify individuals for testing. Genetic testing should include genes associated with ovarian cancer susceptibility, particularly homologous recombination repair genes (e.g., BRCA1, BRCA2, BRIP1, RAD51C, RAD51D, PALB2, ATM) and mismatch repair genes (e.g., MLH1, MSH2, MSH6, EPCAM).

Risk-Reducing Prophylactic Surgery

According to the serous ovarian cancer theory of fallopian tube origin, individuals at high risk with intermediate- to high-risk genetic mutations should consider undergoing risk-reducing surgery to remove both ovaries and fallopian tubes after completing childbearing, which may decrease the risk of ovarian and fallopian tube cancers. Women from the general (low-risk) population who have completed childbearing may benefit from opportunistic salpingectomy during pelvic-abdominal surgeries to reduce their future risk of ovarian and fallopian tube cancers.

Ovarian Tumors in Pregnancy

Ovarian tumors during pregnancy are relatively common, but malignant tumors are rare. Benign tumors, such as mature cystic teratomas and serous cystadenomas, account for 90% of ovarian tumors during pregnancy, while malignant tumors, such as dysgerminomas and serous cystadenocarcinomas, are less frequent. Ovarian tumors during pregnancy are generally asymptomatic in the absence of complications. They may be detected during early pregnancy via gynecological examination or, in the second trimester and beyond, through ultrasound.

Complications are more likely during mid-pregnancy, including torsion of the tumor pedicle. During late pregnancy, tumors may cause fetal malposition, while low-lying tumors may obstruct the pelvic birth canal during labor, leading to difficult delivery or, in some cases, tumor rupture. The increased pelvic blood flow during pregnancy can accelerate tumor growth, raising the risk of malignant dissemination.

The management of benign ovarian tumors during pregnancy involves delayed surgery until after 12 weeks of gestation if detected during early pregnancy to minimize the risk of miscarriage. For tumors discovered in late pregnancy, surgery is typically deferred until full-term delivery, when cesarean section and tumor removal are performed concurrently. In cases of suspected or confirmed malignant ovarian tumors, surgical intervention is prioritized and follows the same principles as in non-pregnant patients.