Endometrial carcinoma (EC) refers to a group of epithelial malignant tumors originating in the endometrium, with adenocarcinoma arising from endometrial glands being the most common type. It is one of the three major malignant tumors of the female reproductive tract, accounting for 7% of all malignancies in women and 20%–30% of those specific to female genital organs. In recent years, the incidence of endometrial carcinoma has been steadily increasing worldwide. It ranks as the most common gynecological malignancy in developed countries of Europe and North America. The majority of cases involve patients in the early stages of the disease. The overall prognosis is relatively favorable, with a 5-year survival rate exceeding 80%.

Associated Risk Factors

The exact cause of endometrial carcinoma remains unclear, but several factors are associated with its occurrence:

Hormonal Factors

Both endogenous and exogenous estrogen are strongly associated with the development of endometrial carcinoma. Functional ovarian tumors, prolonged estrogen exposure without progesterone opposition, and the use of tamoxifen contribute to this association. Long-term unopposed estrogen stimulation can lead to abnormal endometrial hyperplasia, which may progress to malignancy.

Metabolic Factors

Clinical evidence shows that endometrial carcinoma is often associated with obesity, diabetes, and hypertension, collectively known as the "triad" of endometrial carcinoma. These metabolic-related tumors tend to have a relatively favorable prognosis.

Genetic Factors

A small proportion of endometrial carcinoma cases are hereditary, accounting for approximately 5%. The condition most strongly associated with hereditary endometrial carcinoma is Lynch syndrome, also known as hereditary nonpolyposis colorectal cancer (HNPCC). Lynch syndrome is an autosomal dominant disorder caused by mutations in DNA mismatch repair genes. Endometrial carcinoma associated with Lynch syndrome generally occurs at a younger age compared to sporadic cases.

Other Factors

Infertility, as well as menstrual factors such as early menarche and late menopause, have been linked to an increased risk of endometrial carcinoma.

Pathology

In 1983, Bokhman proposed that endometrial carcinoma could be classified into two pathological types: Type I, primarily associated with estrogen and metabolic abnormalities and mostly consisting of endometrioid carcinoma, which has a favorable prognosis; and Type II, unrelated to estrogen and dominated by serous carcinoma, characterized by a higher malignancy and poor prognosis. In 2020, the World Health Organization (WHO) revised the histopathological classification of endometrial carcinoma, introducing molecular subtypes.

Macroscopic Features

The gross appearance does not significantly differ across the histologic subtypes of endometrial carcinoma. It can be categorized into diffuse and focal growth patterns:

- Diffuse: The endometrium appears diffusely thickened, with a rough, uneven surface protruding into the uterine cavity, often accompanied by hemorrhage and necrosis. Tumor infiltration into the deep myometrium or cervix may also occur.

- Focal: Typically located at the uterine fundus or cornu, with smaller lesions presenting as polypoid or cauliflower-like growth.

Histopathological Subtypes

Endometrial carcinoma is predominantly composed of endometrioid carcinoma, while other subtypes, which are more aggressive, include serous carcinoma, clear cell carcinoma, undifferentiated carcinoma, mixed carcinoma, carcinosarcoma, mesonephric adenocarcinoma, mesonephric-like adenocarcinoma, squamous cell carcinoma, and gastrointestinal-type mucinous carcinoma.

Endometrioid Carcinoma

Endometrioid carcinoma is the most common subtype, accounting for 80%–90% of cases. It consists of glandular structures resembling those of proliferative endometrium, forming glandular, villoglandular, or cribriform patterns, and may show squamous differentiation. The tumor cells are arranged in pseudostratified or stratified layers, with mild to moderate atypia and active mitoses. Poorly differentiated endometrioid carcinoma lacks glandular structures, instead presenting as solid nests or sheets. Based on the proportion of the solid component, endometrioid carcinoma is graded as follows: G1 (≤5%), G2 (6%–50%), and G3 (>50%). G1 and G2 are classified as low-grade, while G3 is high-grade. The precursor lesion for endometrioid carcinoma is atypical endometrial hyperplasia (AEH) or endometrioid intraepithelial neoplasia (EIN).

Serous Carcinoma

Serous carcinoma accounts for about 10% of cases and frequently arises from the surface of polyps or atrophic endometrium. The tumor forms complex papillary and glandular structures with irregular morphology. The cancer cells display marked atypia, characterized by large, hyperchromatic nuclei, prominent nucleoli, and active mitotic figures, often accompanied by psammoma bodies. This subtype is highly malignant, with a tendency for deep myometrial invasion, peritoneal involvement, lymph node metastasis, and distant spread. The precursor lesion may be endometrial glandular dysplasia (EmGD). In the absence of myometrial invasion, the condition is termed serous endometrial intraepithelial carcinoma (SEIC), yet extrauterine metastases can still occur.

Clear Cell Carcinoma

Clear cell carcinoma accounts for less than 10% of cases and is characterized by mixed patterns, such as solid, tubular, microcystic, or papillary arrangements. The cancer cells may appear columnar, polygonal, hobnail-shaped, or flat, with clear or eosinophilic cytoplasm and pronounced nuclear atypia. This subtype is associated with high malignancy and a tendency for metastasis.

Undifferentiated and Dedifferentiated Carcinomas

These collectively account for approximately 2% of cases and are associated with poor outcomes. Undifferentiated carcinoma consists of non-cohesive, relatively uniform small to medium-sized cancer cells arranged in solid sheets, lacking distinct glandular, nest-like, or trabecular patterns. The nuclear chromatin is hyperchromatic, and mitotic figures are readily observed. Dedifferentiated carcinoma is characterized by a combination of undifferentiated carcinoma and well-differentiated endometrial carcinoma components.

Mixed Carcinoma

This rare subtype comprises two or more distinct histological types of endometrial carcinoma, with at least one component being clear cell carcinoma or serous carcinoma. The most common combination is a mix of endometrioid carcinoma and serous carcinoma.

Carcinosarcoma

Carcinosarcoma is an uncommon subtype consisting of biphasic differentiation, with high-grade carcinoma and sarcomatous components. The carcinomatous component is often endometrioid or serous carcinoma, though it may also include clear cell or undifferentiated carcinoma. The sarcomatous component is most commonly undifferentiated high-grade sarcoma but may include heterologous elements such as rhabdomyosarcoma, chondrosarcoma, or osteosarcoma. Carcinosarcoma is prone to deep myometrial invasion and lymphatic spread, resulting in poor prognosis. It is essentially considered a metaplastic carcinoma that originates from monoclonal epithelial cells.

Molecular Subtypes

Recent advances have enabled molecular classification of endometrial carcinoma based on genetic features. It is typically categorized into four molecular groups:

- POLE Ultramutated Type: This group has the best prognosis.

- Microsatellite Instability-High (MSI-H)/Mismatch Repair-Deficient (dMMR) Type: This group has an intermediate prognosis.

- Copy Number Low (CNL)/No Specific Molecular Profile (NSMP) Type: This group also has an intermediate prognosis.

- Copy Number High (CNH)/p53 Abnormal Type: This group has the worst prognosis.

This molecular classification aids in precise risk stratification, prognosis assessment, and treatment guidance.

Metastatic Pathways

Most cases of endometrial carcinoma develop slowly and remain confined to the uterine body for an extended period. Certain histological subtypes, however, progress rapidly, leading to metastasis within a short timeframe. The primary metastatic pathways include direct extension, lymphatic spread, and hematogenous dissemination.

Direct Extension

Endometrial carcinoma may spread along the uterine lining. Upward spread can involve the fallopian tubes via the uterine cornu, while downward spread can affect the cervical canal and vagina. The cancer primarily infiltrates the myometrium, potentially reaching the uterine serosa. It may also implant on the peritoneum, rectouterine pouch (Pouch of Douglas), omentum, and other pelvic and abdominal structures.

Lymphatic Spread

Lymphatic metastasis is the most common pathway of endometrial carcinoma dissemination. High-grade tumors, deep myometrial invasion, or extensive lymphovascular space invasion increase the likelihood of lymphatic spread. The metastatic route depends on the tumor’s location:

- Lesions at the uterine fundus often metastasize through the lymphatic network of the upper broad ligament to the para-aortic lymph nodes.

- Lesions at the uterine cornu or the anterior upper uterine wall may spread via the lymphatics of the round ligament to the inguinal lymph nodes.

- Lesions in the lower uterine segment or those involving the cervical canal share lymphatic drainage pathways with cervical cancer, potentially affecting the parametrium, obturator lymph nodes, internal iliac lymph nodes, external iliac lymph nodes, and common iliac lymph nodes.

- Lesions in the posterior uterine wall may spread along the uterosacral ligament to the pararectal lymph nodes.

The pathways of lymphatic spread provide anatomical guidance for the identification of sentinel lymph nodes (SLN).

Hematogenous Spread

In advanced cases, endometrial carcinoma may metastasize hematogenously to distant organs. Common metastatic sites include the lungs, liver, and bones.

Staging

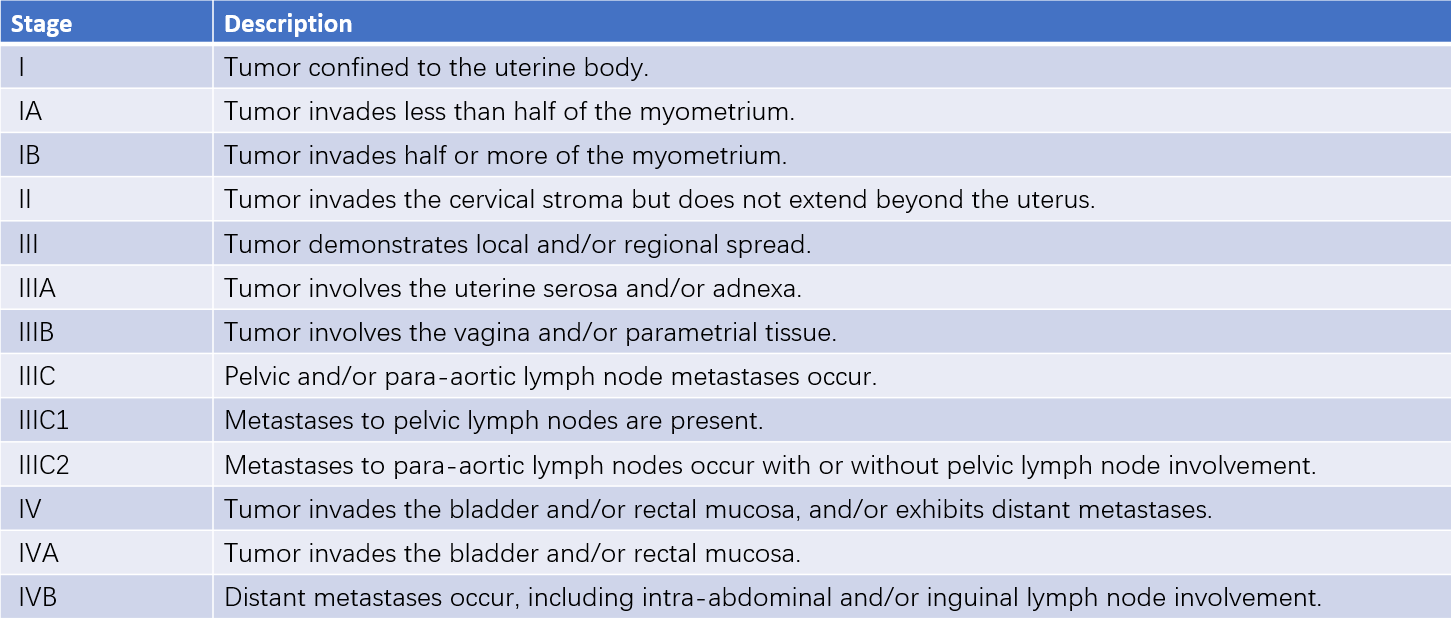

In 1971, the International Federation of Gynecology and Obstetrics (FIGO) introduced a clinical staging system based on preoperative assessments (including physical examinations and fractional curettage). This system remains in use for patients who are not candidates for surgery. In 1988, FIGO introduced the surgical-pathological staging system, which underwent revisions in 2009 and, most recently, in 2023.

Table 1 Surgical-pathological staging of endometrial carcinoma (FIGO, 2009)

The 2023 FIGO staging system includes significant updates, incorporating pathological characteristics such as histologic subtype, tumor grade, and lymphovascular space invasion. Lymph node metastasis dimensions, ovarian involvement, and pelvic/abdominal spread were also more precisely categorized. Notably, molecular subtypes have been integrated into the staging adjustments. For example, patients with Stage I/II tumors classified as POLE-ultramutated may have their stage downgraded to IA, whereas those with Stage I tumors involving p53 mutations may have their stage upgraded to IIC if the myometrium is involved. This new staging system offers a more accurate prognosis and facilitates treatment planning. However, the 2023 FIGO staging remains contentious, and FIGO 2009 staging continues to be the primary guideline in clinical practice.

Clinical Manifestations

Symptoms

Approximately 90% of patients present with abnormal vaginal bleeding or increased vaginal discharge.

- Vaginal Bleeding: The most common symptom is postmenopausal vaginal bleeding. In premenopausal women, increased menstrual flow, prolonged menses, or irregular menstrual cycles may occur.

- Increased Vaginal Discharge: Discharge is often serosanguineous or watery. When infection is present, the discharge may be purulent and bloody, accompanied by a foul odor.

- Lower Abdominal Pain and Other Symptoms: When the tumor invades the cervical canal, pyometra (uterine pus accumulation) may develop, leading to lower abdominal distension, cramping pain, or spasmodic pain. Tumor invasion into surrounding tissues or nerve compression can cause lower abdominal or lumbosacral pain. Late-stage symptoms may include anemia, weight loss, and cachexia.

Signs

In early-stage disease, gynecological examinations may not reveal abnormalities. In advanced cases, the uterus may be enlarged. When pyometra is present, significant uterine tenderness may develop. Occasionally, cancer tissue may protrude from the cervical canal, bleeding easily upon contact. If the tumor invades surrounding tissues, uterine mobility may become restricted, or irregular nodular masses may be palpable in the parametrium.

Diagnosis

Medical History and Clinical Presentation

Postmenopausal vaginal bleeding or menstrual irregularities during the perimenopausal period require exclusion of endometrial carcinoma before considering treatment for benign conditions. Cases with abnormal uterine bleeding accompanied by the following risk factors should raise suspicion for endometrial carcinoma:

- Presence of high-risk factors for endometrial carcinoma, such as obesity, diabetes, or other metabolic syndromes.

- History of infertility or delayed menopause.

- Prolonged use of estrogen, tamoxifen, or conditions associated with elevated estrogen levels.

- Family history of endometrial carcinoma, colorectal cancer, breast cancer, or Lynch syndrome.

Imaging Tests

Ultrasound

This modality is used to assess uterine size, uterine cavity morphology, intrauterine lesions, endometrial thickness, myometrial invasion, and its extent. It provides a preliminary evaluation of the cause of abnormal uterine bleeding. Typical ultrasonographic features of endometrial carcinoma include heterogeneous echoes within the uterine cavity, often accompanied by prominent blood flow signals. Postmenopausal endometrial thickness greater than 5 mm warrants further evaluation.

Magnetic Resonance Imaging (MRI) and CT Scans

These modalities evaluate tumor location and extent. MRI provides better accuracy in determining the depth of myometrial invasion and cervical stromal involvement. CT scans can assist in assessing extrauterine metastases.

PET/CT

This modality offers functional imaging of tumor tissues and is often used in advanced or recurrent cases for qualitative and localization diagnoses.

Biopsy and Pathological Assessment

Histopathological evaluation remains the definitive method for diagnosing endometrial carcinoma.

Diagnostic Curettage

This is the most commonly used diagnostic method. Fractional curettage can obtain endometrial and cervical tissues simultaneously for pathological examination. Diagnostic curettage may miss smaller lesions.

Hysteroscopy

This technique allows direct visualization of the uterine cavity and cervical canal for the presence, size, and location of cancer lesions. Targeted biopsies under direct visualization can reduce the likelihood of missed diagnoses. However, concerns about whether hysteroscopy promotes cancer cell dissemination remain unresolved. In cases with a high clinical suspicion of endometrial carcinoma, direct biopsy without routine hysteroscopy may be an alternative.

Other Tests

Endometrial Cytology or Small-Volume Tissue Sampling

This method is simple and involves obtaining endometrial cells or tissue fragments using a sampling device. These samples are used for cytopathological and small-volume histopathological evaluations.

Tumor Marker Assays

Serum tumor markers such as CA125 may be elevated in cases with extrauterine metastasis or serous carcinoma, aiding in disease assessment and treatment monitoring.

Genetic Testing and Molecular Subtyping

If resources allow, genetic testing and molecular subtyping are recommended as they provide guidance for treatment planning.

Differential Diagnosis

Abnormal vaginal bleeding during the postmenopausal or perimenopausal period is the most common symptom of endometrial carcinoma. This condition must be differentiated from diseases that also present with vaginal bleeding.

Non-Organic Abnormal Uterine Bleeding

This condition is characterized by symptoms such as menstrual irregularities, excessive menstrual flow, prolonged menses, or irregular vaginal bleeding. Gynecological examinations show no organic abnormalities, and histopathological evaluation forms the basis of differentiation.

Submucosal Uterine Fibroids or Endometrial Polyps

These conditions present with excessive or irregular vaginal bleeding and can be differentiated through ultrasound, hysteroscopy, and diagnostic curettage.

Endophytic Cervical Cancer, Uterine Sarcoma, or Fallopian Tube Cancer

These conditions commonly manifest with increased vaginal discharge or irregular bleeding. Endophytic cervical cancer involves lesions within the cervical canal, leading to cervical thickening and hardening with a barrel-shaped appearance. Uterine sarcoma may present with significant uterine enlargement and a softer consistency. Fallopian tube cancer is typically associated with lower abdominal discomfort, intermittent vaginal discharge, and adnexal masses. Fractional curettage and imaging studies aid in differential diagnosis.

Atrophic Vaginitis

This condition primarily presents with blood-tinged vaginal discharge. Examination typically shows thinning of the vaginal mucosa, congestion, pinpoint hemorrhages, or increased secretions. Ultrasound commonly reveals no abnormalities in the uterine cavity. Symptoms often improve with treatment. If necessary, anti-infective therapy can be initiated before performing diagnostic curettage.

Treatment

Treatment plans for endometrial carcinoma are determined by factors such as the patient's age, overall health, fertility preservation needs, disease stage, histological type, tumor grade, and molecular subtype. The primary treatment modality is surgery. Patients with risk factors for recurrence often undergo adjuvant therapy after surgery. Advanced or recurrent cases usually require multimodal treatment. Young patients with early-stage, low-risk disease may receive fertility-preserving hormonal therapy.

Fertility-Preserving Therapy

Strict criteria must be met to consider fertility-preserving therapy:

- Age under 40–45, with a strong desire to have children.

- Histopathology confirming endometrioid adenocarcinoma with low-grade features (G1).

- Imaging indicating that the tumor is confined to the endometrium.

- No contraindications to progestin therapy.

- Pre-treatment evaluation by genetic and reproductive medicine specialists confirming no other infertility issues.

- Informed consent and the ability to undergo close follow-up.

High-dose progestins are the first-line medical treatment. After 3–6 months of treatment, biopsies are performed to evaluate therapeutic efficacy. If no response or disease progression is observed after 6 months, discontinuation of medical therapy in favor of surgical treatment is recommended.

Fertility-preserving therapy is not considered standard treatment for endometrial carcinoma. Risks of recurrence and progression remain. Patients achieving complete remission are encouraged to pursue pregnancy actively. After childbearing, removal of the uterus is recommended. If the patient strongly desires to retain their uterus, rigorous follow-up is required.

Surgical Treatment

Surgery is the standard treatment for most cases. Patients with early-stage disease undergo comprehensive staging surgery, while those with advanced-stage disease typically receive cytoreductive surgery. Surgery can be performed via an abdominal or laparoscopic approach, with laparoscopic surgery being preferred. Principles such as the use of uterine manipulators and a no-touch technique to minimize tumor spread should be followed.

Comprehensive staging surgery steps:

- Collection of peritoneal fluid or lavage for cytological analysis.

- Thorough inspection of the pelvic and abdominal cavities, with biopsy of any suspicious lesions for frozen section analysis where necessary.

- Extrafascial hysterectomy with bilateral salpingo-oophorectomy. The uterus is routinely examined intraoperatively to confirm tumor location and invasion extent, with frozen section analysis performed if required.

- Lymphadenectomy, including pelvic and para-aortic lymph nodes up to the level of the renal vessels.

- For specific histological subtypes such as serous carcinoma or clear cell carcinoma, omentectomy or omental biopsy is advised.

- For stromal invasion of the uterine cervix confirmed through preoperative imaging, total hysterectomy is generally preferred. In cases where surgical margins are a concern, modified radical hysterectomy may be selected.

For disease extending beyond the uterus, cytoreductive surgery to remove all macroscopic lesions is recommended.

In patients younger than 45 years with low-grade, endometrioid carcinoma invading less than 50% of the myometrium and no evidence of ovarian or extrauterine metastases, ovarian preservation may be considered. However, bilateral salpingectomy is recommended. For those with BRCA mutations, a family history of ovarian or breast cancer, or Lynch syndrome, ovarian preservation is generally discouraged.

Pelvic and para-aortic lymphadenectomy is a critical component of surgical staging. Sentinel lymph node biopsy can replace systematic lymph node dissection in patients with endometrial carcinoma limited to the uterine body confirmed pre- or intraoperatively. Patients with endometrioid carcinoma satisfying the Mayo criteria may forgo lymphadenectomy:

- Myometrial invasion depth <50%.

- Tumor diameter <2 cm.

- Low-grade histology (G1 or G2).

For all patients with high-risk factors, comprehensive staging surgery remains essential. Cytoreductive surgery is indicated for advanced disease.

Postoperative adjuvant therapy depends on risk stratification, considering factors such as age, histologic type, tumor grade, lymphovascular space invasion, depth of myometrial invasion, cervical stromal involvement, lymph node metastasis, and/or extrauterine spread:

- Low-risk: Stage IA, low-grade, endometrioid carcinoma.

- Intermediate-risk: Low-risk patients aged ≥60 or with focal lymphovascular space invasion; Stage IB, low-grade, endometrioid carcinoma; Stage IA, high-grade, endometrioid carcinoma; Stage IA without myometrial invasion for special histological types.

- High–intermediate risk: Low- or intermediate-risk with extensive lymphovascular space invasion; Stage IB, high-grade, endometrioid carcinoma; Stage II endometrioid carcinoma.

- High-risk: Special histological types with myometrial invasion; Stage III/IV of any tumor grade or histology.

Low-risk patients require monitoring without adjuvant therapy. Intermediate-risk patients may undergo brachytherapy or observation. High–intermediate-risk patients may receive pelvic radiotherapy ± chemotherapy, while high-risk patients may receive chemotherapy ± radiotherapy.

Radiation Therapy

Radiation therapy is an effective treatment option for endometrial carcinoma and includes brachytherapy and external beam radiation therapy (EBRT).

- Definitive Radiotherapy: Used for patients who cannot undergo surgery due to contraindications or for those with advanced, unresectable disease. It often combines brachytherapy with EBRT.

- Neoadjuvant Radiotherapy: Often employed in locally advanced, unresectable cases to control or shrink tumors, providing opportunities for surgery or limiting surgical extent. Its application is relatively rare.

- Postoperative Adjuvant Radiotherapy: Intermediate- and high–intermediate-risk patients are typically offered adjuvant radiotherapy. High-risk patients may receive radiotherapy in addition to chemotherapy.

Hormonal Therapy

In addition to fertility-preserving treatment, hormonal therapy is primarily utilized for advanced or recurrent disease. High-dose, long-term progestins are commonly employed, including medroxyprogesterone acetate (250–500 mg/day), megestrol acetate (160–320 mg/day), and anti-estrogen agents such as tamoxifen (20–40 mg/day). Aromatase inhibitors (e.g., letrozole at 2.5 mg/day) or intrauterine devices releasing levonorgestrel (LNG-IUS) may also be used. This approach is most suitable for recurrent cases with low-grade tumors, PR-positive expression, small tumor burden, and slow growth.

Chemotherapy

Adjuvant chemotherapy is often necessary for high-risk patients following surgery or for those with advanced/metastatic or recurrent disease. Common chemotherapeutic agents include carboplatin, cisplatin, paclitaxel, and doxorubicin, often administered in combination. Platinum-based regimens combined with paclitaxel are considered the first-line choice. Chemotherapy is typically used for patients with high-grade, aggressive, large, or rapidly growing lesions.

Targeted and Immunotherapy

Bevacizumab in combination with chemotherapy has shown improved efficacy in recurrent endometrial carcinoma, particularly in the p53-abnormal subtype. In advanced/metastatic or recurrent cases, the combination of immunotherapy (e.g., pembrolizumab) with chemotherapy has significantly enhanced survival in first-line treatment. For advanced/metastatic or recurrent treatment-refractory cases, MSI-H/dMMR or TMB-H patients derive remarkable benefit from immune checkpoint inhibitors as monotherapy. In MSS/pMMR patients, the combination of pembrolizumab with lenvatinib demonstrates superior outcomes compared to non-platinum chemotherapeutic agents.

Prognosis

The overall prognosis of endometrial carcinoma is relatively favorable, with a 5-year survival rate exceeding 80%. However, aggressive histological subtypes are associated with poor outcomes. Prognostic factors primarily include the following:

- Surgical-pathological stage, histological type, histological grade, lymphovascular space invasion, and molecular subtype.

- The patient’s age and overall health status.

- The choice of treatment plan.

Follow-Up

Regular follow-up is recommended after treatment. Within the first 2–3 years post-surgery, follow-up visits should be conducted every 3–6 months. Between years 3 and 5, follow-up should occur every 6–12 months. After 5 years, annual visits are sufficient. Follow-up assessments should consist of a detailed medical history, gynecological examination, abdominal and pelvic ultrasound, and serum CA125 testing. Additional imaging studies such as CT, MRI, or PET/CT may be performed if necessary.

Prevention

Preventive strategies include the following measures:

- Attention to the diagnosis and treatment of postmenopausal vaginal bleeding and menstrual irregularities during the perimenopausal period.

- Appropriate use of estrogen, including clear indications and proper administration methods.

- Close monitoring or surveillance of high-risk populations, such as individuals with obesity, infertility, delayed menopause, or prolonged use of estrogen and tamoxifen.

- Enhanced surveillance for women with Lynch syndrome, which may involve annual gynecological examinations and transvaginal ultrasound beginning at the age of 30–35 years. Endometrial biopsy can be conducted when necessary. Decisions regarding prophylactic hysterectomy should be individualized based on factors such as the patient’s reproductive plans and the specific pathogenic gene mutation type.