Uterine sarcoma is a rare malignant mesenchymal tumor that originates from the uterine myometrium, endometrial stroma, or connective tissue of the myometrium. It accounts for approximately 1% of all female genital tract malignancies and 3%–7% of uterine malignancies. It is more commonly observed in women aged 40–60 years and older, with a high level of malignancy.

Histogenesis and Pathology

Based on its tissue of origin, uterine sarcoma is classified into leiomyosarcoma, endometrial stromal sarcoma, and other mesenchymal-derived malignant tumors.

Leiomyosarcoma (LMS)

Leiomyosarcoma is a malignant tumor with smooth muscle differentiation and represents the most common type of uterine malignant mesenchymal tumor. It originates from the smooth muscle of the myometrium or vascular walls within the myometrium. The tumor exhibits infiltrative growth with no distinct boundary from the surrounding myometrium. Typically solitary, these tumors are often large, with an average diameter of 10 cm. They have a soft consistency and frequently present with necrosis, hemorrhage, and a fish-flesh appearance on cross-section, although they may sometimes have a gelatinous appearance. Histologically, leiomyosarcomas include spindle cell, epithelioid, and myxoid subtypes, of which the spindle cell subtype is most common. Microscopically, tumor cells are spindle-shaped or pleomorphic, often arranged in irregular bundles. Marked cellular size variation, nuclear atypia, and hyperchromatic nuclei with prominent nucleoli are characteristic features. Extensive atypical nuclei, abundant mitotic figures (≥10/10 HPF), and tumor cell coagulative necrosis are key diagnostic criteria, with the presence of at least two being sufficient to diagnose leiomyosarcoma. Leiomyosarcoma carries a high degree of malignancy and frequently metastasizes hematogenously, resulting in poor prognosis.

Endometrial Stromal Sarcoma (ESS)

Endometrial stromal sarcoma originates from endometrial stromal cells and includes two main types:

Low-Grade Endometrial Stromal Sarcoma (LGESS)

LGESS is the second most common uterine mesenchymal malignancy and exhibits relatively indolent biological behavior. Grossly, the tumor may appear as a polypoid or nodular lesion protruding into the uterine cavity or infiltrating the myometrium, often with unclear margins. Microscopically, the tumor consists of cells resembling proliferative-phase endometrial stromal cells, with uniform size, scant cytoplasm, minimal or mild nuclear atypia, and fewer than 5 mitotic figures/10 HPF. Necrosis is either absent or minimal. Tumor cells tend to form irregular tongues or jagged cell clusters that diffusely infiltrate the myometrium, possibly with vascular invasion. The tumor is rich in small arterioles or thin-walled vessels resembling spiral arteries in normal endometrium. Approximately two-thirds of cases involve fusion gene abnormalities, most commonly JAZF1-SUZ12 fusions. LGESS has a propensity for metastasizing to paracervical tissues rather than lymph nodes or lungs. Recurrence tends to occur late, with a mean recurrence time of 5 years after initial treatment.

High-Grade Endometrial Stromal Sarcoma (HGESS)

HGESS typically presents as multiple polypoid lesions within the uterine cavity or as multiple nodules in the myometrium, often appearing tan-brown to yellow with fish-flesh cross-sections accompanied by hemorrhage and necrosis. Microscopically, the tumor demonstrates various invasive growth patterns, including expansive, permeative, or infiltrative growth, with frequent vascular invasion and tumor cell necrosis. Mitotic figures are typically greater than 10/10 HPF. The tumor is predominantly composed of high-grade round cells with scant cytoplasm and discernible nucleoli. HGESS is often associated with specific genetic alterations, including YWHAE-NUTM2A/B fusions, ZC3H7B-BCOR fusions, BCOR internal tandem duplications, and, less commonly, EPC1-BCOR, JAZF1-BCORL1, and BRD8-PHF1 fusions. The malignancy is highly aggressive, frequently metastasizing outside the uterus, with poor patient outcomes.

Undifferentiated Uterine Sarcoma (UUS)

UUS is a high-grade sarcoma arising from the uterus without specific differentiation and histologically distinct from proliferative-phase endometrial stroma. It is a diagnosis of exclusion. Grossly, it often appears as a polypoid mass protruding into the uterine cavity or as an intramural lesion with a fish-flesh cross-section, often accompanied by hemorrhage and necrosis. Microscopically, the tumor shows poorly differentiated cells with marked atypia, active mitosis, "sheet-like" or "herringbone-like" arrangements, and destructive infiltration into the myometrium, often with vascular invasion. Rarely, low-grade ESS components may be observed, suggesting some tumors originate from endometrial stroma. UUS is highly aggressive, with an extremely poor prognosis.

Adenosarcoma

Adenosarcoma is a biphasic malignant tumor containing benign or atypical glandular epithelium and sarcomatous stromal components. It occurs predominantly in postmenopausal women but may also appear in adolescence or reproductive-age individuals. Typical adenosarcomas manifest as polypoid masses protruding into the uterine cavity, often as solitary, solid tumors that fill the cavity and may protrude through the cervix. Grossly, it often appears grayish-red with small cystic spaces and may be accompanied by hemorrhage or necrosis. Microscopically, cellular stroma forms papillary or polypoid projections into cystically dilated glandular lumina, compressing glandular structures into clefts. The epithelial component is often of endometrial type, surrounded by dense stromal cells that create a "cuffing" structure or "proliferative layer." Stromal components are typically homologous and low-grade, with mild atypia and low mitotic activity (2–4/10 HPF). In some cases, sarcomatous overgrowth (SO) occurs when pure sarcoma accounts for more than 25% of the tumor. The overgrowth component is usually high-grade, occasionally with heterologous elements, and exhibits high invasiveness and poor prognosis. In contrast, tumors without sarcomatous overgrowth have a relatively favorable prognosis.

Other Mesenchymal Uterine Tumors

Rare mesenchymal-derived uterine malignancies include perivascular epithelioid cell tumors (PEComa), inflammatory myofibroblastic tumors, and other mesenchymal tumors such as rhabdomyosarcoma, angiosarcoma, and liposarcoma. These tumors are exceptionally uncommon.

Metastatic Pathways

The metastatic pathways of uterine sarcomas include hematogenous spread, direct invasion, and lymphatic metastasis. Hematogenous spread and direct invasion are more common than lymphatic metastasis, and the modes of metastasis vary slightly depending on the pathological subtype. Leiomyosarcoma frequently metastasizes hematogenously, as seen in cases of lung metastasis. Low-grade endometrial stromal sarcoma tends to spread to the parametrium and rarely involves lymphatic or hematogenous metastasis. High-grade endometrial stromal sarcoma and undifferentiated uterine sarcoma exhibit a high degree of malignancy and may show infiltrative and destructive growth. They can directly invade adjacent organs, exhibit vascular infiltration, and metastasize to regional lymph nodes via the lymphatic system.

Clinical Manifestations

Symptoms

Uterine sarcomas generally lack specific symptoms, especially in the early stages. As the disease progresses, the following symptoms may appear:

- Irregular vaginal bleeding: This is the most common symptom, with variable amounts of bleeding.

- Abdominal pain: Rapid tumor growth, uterine enlargement, intratumoral hemorrhage, necrosis, or rupture of the uterine wall may cause acute abdominal pain.

- Abdominal mass: Patients may report a palpable abdominal mass in the lower abdomen that enlarges quickly.

- Compression symptoms and others: Tumors compressing the bladder or rectum may cause urinary frequency, urgency, retention, or constipation. In the advanced stages, systemic symptoms such as emaciation, anemia, low-grade fever, or symptoms associated with metastatic involvement of the lungs or brain may occur. Tumors prolapsing from the uterine cavity into the vagina may produce significant discharge.

Signs

Gynecological examination may reveal an enlarged and irregularly shaped uterus. Polypoid or myoma-like masses, purple-red in color and prone to bleeding, may be visible at the cervical os. Secondary infection may result in necrosis and purulent discharge. In advanced cases, the sarcoma may involve the pelvic sidewall, causing fixation of the uterus and limited mobility. It may also metastasize to the intestines or peritoneal cavity, though ascites is uncommon.

Diagnosis

Preoperative diagnosis of uterine sarcoma is challenging due to the absence of specific clinical manifestations. Suspicion should be raised for cervical or intrauterine masses in children, adolescents, or peri- and postmenopausal women, particularly in cases of rapidly enlarging uterine fibroids accompanied by pain. Intraoperative findings such as indistinct margins of a suspected fibroid should also prompt consideration of sarcoma.

Adjuvant diagnostic methods include transvaginal Doppler ultrasound, CT, MRI, and diagnostic curettage. Definitive diagnosis relies on histopathological examination. CT can assess the size, location, and metastatic status of the lesion, while MRI offers superior differentiation of uterine sarcoma. Transvaginal Doppler ultrasound is commonly used but has limited diagnostic specificity, and PET/CT may be pursued, if necessary, to evaluate systemic metastases.

Clinical Staging

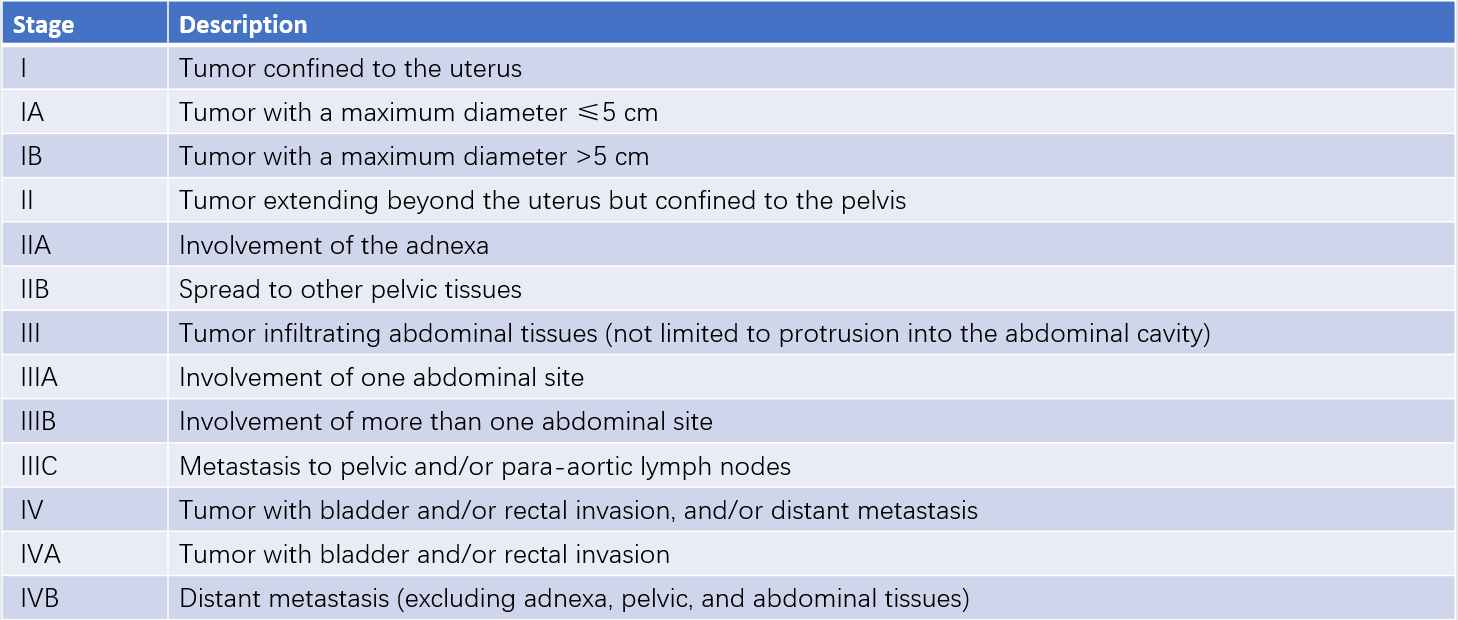

The staging of uterine sarcoma follows the surgical-pathological system established by the International Federation of Gynecology and Obstetrics (FIGO).

Table 1 Surgical pathologic staging for uterine leiomyosarcoma and endometrial stromal sarcoma (FIGO, 2009)

Treatment

The primary treatment for uterine sarcoma is surgical intervention, followed by individualized adjuvant therapy based on pathological subtype and surgical stage.

Surgical Treatment

Uterine sarcoma is often diagnosed postoperatively through pathological examination. Comprehensive evaluation—including pathological subtype, initial surgical approach, and imaging results—determines the need for reoperation and the extent of surgery. The standard surgical procedure is total hysterectomy with bilateral salpingo-oophorectomy via extrafascial technique. The uterus should be removed intact, and morcellation of the tumor or uterus within the abdominal cavity must be avoided. For extramural lesions, complete resection is performed.

Routine systematic retroperitoneal lymphadenectomy is not recommended; however, suspicious or enlarged lymph nodes identified intraoperatively should be excised. In cases of low-grade endometrial stromal sarcoma or tumors with high expression of estrogen/progesterone receptors, bilateral salpingo-oophorectomy is recommended. For young patients with early-stage leiomyosarcoma and estrogen/progesterone receptor-negative tumors who desire ovarian preservation, a thorough evaluation and informed consent regarding risks are necessary. Fertility-sparing surgery should be approached cautiously in uterine sarcoma patients.

Postoperative Adjuvant Therapy

Adjuvant treatments include hormonal therapy, chemotherapy, and radiotherapy.

Low-Grade Endometrial Stromal Sarcoma and Adenosarcoma Without Sarcomatous Overgrowth

Stage I patients who have undergone bilateral salpingo-oophorectomy or are postmenopausal may be observed or receive hormonal therapy. Stage II–IV patients typically receive hormonal therapy ± external beam radiotherapy (EBRT). Aromatase inhibitors are the preferred hormonal agents, but GnRH agonists, medroxyprogesterone acetate, or megestrol acetate may also be used.

Adenosarcoma With Sarcomatous Overgrowth

Stage I patients who have undergone bilateral salpingo-oophorectomy or are postmenopausal may be observed. Stage II–IV patients may undergo systemic therapy ± EBRT.

High-Grade Endometrial Stromal Sarcoma, Leiomyosarcoma, Undifferentiated Uterine Sarcoma, and Other Sarcomas:

Stage I patients may be observed postoperatively, with hormonal therapy considered for estrogen/progesterone receptor-positive tumors. Stage II–III patients with fully resected lesions and negative margins may undergo observation or systemic therapy and/or pelvic EBRT. Stage IVA patients may receive systemic therapy and/or EBRT. For stage IVB patients, systemic therapy ± palliative EBRT is recommended. Chemotherapy regimens generally include doxorubicin monotherapy or combination regimens, such as gemcitabine plus docetaxel.

Prognosis and Follow-Up

Prognosis depends on the sarcoma subtype, disease stage, and treatment method. Low-grade endometrial stromal sarcomas and adenosarcomas without sarcomatous overgrowth have relatively favorable outcomes. High-grade endometrial stromal sarcomas and leiomyosarcomas have poor prognosis, while undifferentiated uterine sarcomas have the worst outcomes.

Regular follow-up is required post-treatment. Follow-up evaluations should include a comprehensive physical exam, gynecological examination, imaging studies (CT and MRI), and health education. Imaging is typically scheduled every 3–4 months during the first 3 years, every 6–12 months in years 4–5, and every 1–2 years during years 6–10, based on the tumor's pathological type, grade, and initial stage, for a total of 5 years.