Uterine myoma (also known as leiomyoma) is the most common benign tumor of the female reproductive system and the most frequent benign tumor in the human body. It is composed of smooth muscle and connective tissue. It commonly occurs in women aged 30 to 50, while it is rare in those under 20. Studies indicate that 60% to 80% of women have uterine myomas of varying sizes. However, because many cases are asymptomatic, the clinically reported prevalence is significantly lower than the true prevalence. The prevalence of uterine myomas varies among different racial groups.

Factors Related to Pathogenesis

Uterine myomas are hormone-dependent tumors, although their exact pathogenesis remains unclear. They are common in women of reproductive age, rare before puberty, and tend to shrink or regress after menopause, indicating a clear association with female hormones. The conversion of estrone to estradiol within myoma tissues is significantly lower than in normal uterine muscle, while estrogen receptor expression is considerably higher. This suggests that heightened sensitivity of myoma tissue to estrogen is one of the key mechanisms of tumor development. Furthermore, progesterone plays a role in promoting mitosis of myoma cells and stimulating tumor growth. Research has also shown that the formation of uterine myomas may be linked to chromosomal abnormalities and genetic mutations, such as chromosomal translocations, deletions, MED12 gene mutations, and increased growth factors that promote tumor growth.

Classification

Classification by Location of Growth

This can be classified into:

- Uterine body myomas: Approximately 90%.

- Cervical myomas: Approximately 10%.

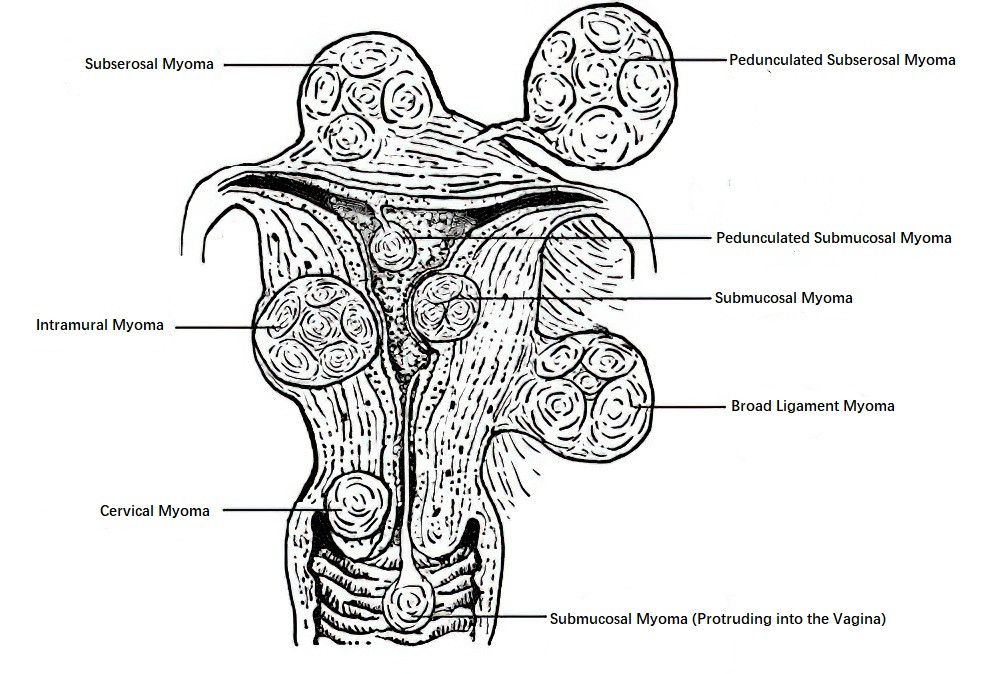

Classification by Relationship to the Myometrium

This can be classified into:

- Intramural Myoma: Comprises 60%–70%. The tumor grows within the myometrium and is completely surrounded by muscle tissue.

- Subserous Myoma: Accounts for approximately 20%. The tumor grows outward toward the serosal surface of the uterus and protrudes beyond the uterine surface. If the tumor continues to grow outward, connected to the uterus only by a stalk, it is called a pedunculated subserous myoma. Blood supply is provided through vessels in the stalk, and insufficient blood supply can lead to degeneration and necrosis. If the stalk undergoes torsion and rupture, free myomas may form. Tumors growing laterally towards the broad ligament between its two leaves are referred to as broad ligament myomas.

- Submucous Myoma: Accounts for 10%–15%. The tumor grows inward toward the uterine cavity and protrudes into it, covered by the endometrium. Submucous myomas often form stalks and, when protruding into the uterine cavity, may be treated as foreign bodies, leading to uterine contractions. In some cases, the tumor may be expelled through the cervical os and extend into the vaginal canal.

Figure 1 Schematic diagram of uterine myoma classification

Uterine myomas are often multiple, and various types can coexist within the same uterus, collectively termed multiple uterine myomas.

FIGO Classification

In addition to the above classical classification, the International Federation of Gynecology and Obstetrics (FIGO) proposed a system in 2011, categorizing uterine myomas into types 0 through 8 based on their location within the uterine wall. This classification is increasingly being adopted in clinical practice.

Pathology

Uterine myomas consist of smooth muscle and connective tissue, and their pathological diagnosis is termed uterine leiomyoma.

Gross Pathology

Uterine leiomyomas appear as solid, spherical nodules with varying sizes. They have a smooth surface, are denser than the surrounding myometrium, and compress adjacent tissues to form a pseudocapsule. A loose reticular plane exists between the pseudocapsule and the tumor, making it easy to enucleate. When the tumor grows large or multiple tumors fuse together, the shape may become irregular. Cross-sections are grayish-white and often display a whorled or woven appearance. The color and density depend on the extent of fibrous connective tissue and secondary changes.

Microscopic Pathology

Uterine myomas are composed of spindle-shaped smooth muscle cells and varying amounts of fibrous connective tissue. Tumor cells are similar to normal smooth muscle cells, forming whorled or fascicular patterns. The cytoplasm is eosinophilic, and nuclei are rod-shaped with blunt, rounded ends. Mitotic figures are rare.

Types of Degeneration in Uterine Myomas

Hyaline Degeneration

Also known as transparent degeneration, it is the most common type. Whorled patterns in the myoma are replaced by uniform, transparent material. Microscopically, myocytes in affected areas disappear and are replaced by pink, homogeneous, structureless collagen fibers.

Cystic Degeneration

Progression of hyaline degeneration, infarction, or severe edema can lead to cystic degeneration. The tumor softens, forming variable-sized cavities that contain colorless fluid or gelatinous material.

Red Degeneration

Common during pregnancy or the puerperium, it is a form of necrosis associated with unclear mechanisms, possibly caused by thrombus formation within small blood vessels, hemolysis, or infiltration of hemoglobin into muscle fibers. Patients may experience severe abdominal pain, nausea, vomiting, fever, and elevated white blood cell counts. The tumor increases in size, becomes tender, and macroscopically appears dark red and soft, without a whorled pattern. Microscopically, venous thrombosis, widespread hemorrhage, hemolysis, and nuclear dissolution of myoma cells are observed. However, cytoplasmic outlines remain intact.

Calcification

Relatively rare, it is more common in pedunculated subserous myomas with poor blood supply or in postmenopausal women. Calcification appears as distinct shadows on imaging, and microscopically, calcium deposits are seen as blue granules or layered structures.

Sarcomatous Change

Rare, this occurs in only 0.4%-0.8% of cases. Recent studies indicate that uterine leiomyomas and leiomyosarcomas have distinct karyotypes and origins. Only a minority of leiomyosarcomas share genetic features with leiomyomas, suggesting possible malignant transformation. Rapid growth of myomas before menopause does not indicate sarcomatous change, though increased size after menopause may warrant suspicion of malignancy.

Clinical Manifestations

Symptoms

Clinical manifestations are often absent, and uterine myomas are usually detected during routine physical examinations. Symptoms depend on the location, size, number, and presence of degeneration of the myomas. Common symptoms include the following:

Increased Menstrual Flow and Prolonged Menstrual Periods

These are the most common symptoms of uterine myomas. They are frequently seen in cases of large intramural or submucous myomas. The tumor increases the size of the uterus and the endometrial surface area, while also impairing uterine contractions. Additionally, the tumor may compress veins near the endometrium, leading to congestion and venous dilation, which can result in heavier and prolonged menstrual bleeding. If necrosis or infection occurs in a submucous myoma, there may also be irregular vaginal bleeding or increased purulent vaginal discharge. Chronic heavy bleeding may cause secondary anemia, leading to symptoms such as fatigue and palpitations.

Lower Abdominal Mass

As uterine myomas grow, the uterus may reach a size equivalent to a 3-month pregnancy, allowing a mass to be palpated in the lower abdomen. Submucous myomas may even protrude into or outside the vaginal canal, leading patients to seek medical attention for a prolapsing mass.

Increased Vaginal Discharge

Intramural myomas can expand the uterine cavity, resulting in increased glandular secretion from the endometrium, which causes increased vaginal discharge. If submucous myomas develop necrosis or infection, the vaginal discharge may become bloody or purulent with a foul odor.

Compression Symptoms

A myoma in the lower anterior uterine wall may compress the bladder, causing urinary frequency. Cervical myomas can cause difficulty in urination or urinary retention. Posterior wall myomas may result in constipation and other bowel symptoms. Broad ligament myomas or large cervical myomas growing laterally may embed into the pelvis, compressing the ureters, and leading to upper ureteral dilation or even hydronephrosis.

Infertility

Uterine myomas are responsible for infertility in 1%–2% of cases, with submucous myomas being the most common cause. There is no strong evidence suggesting that subserous myomas or intramural myomas not affecting the uterine cavity cause infertility.

Other Symptoms

Patients may also experience lower abdominal heaviness, lower back pain, or pelvic discomfort. Red degeneration of a myoma may cause acute lower abdominal pain accompanied by nausea, vomiting, fever, and localized tenderness. Pedunculated subserous myomas undergoing torsion may cause acute abdominal pain. Submucous myomas being expelled from the uterine cavity may also result in abdominal pain.

Signs

Physical signs vary depending on the size, location, number, and degeneration of the myomas. Large myomas may present as palpable, solid masses in the lower abdomen. Gynecological examination may reveal an enlarged uterus with an irregular surface and one or more nodular protrusions. Subserous myomas often appear as single, solid, spherical masses connected to the uterus via a peduncle. Submucous myomas confined to the uterine cavity may cause uniform uterine enlargement, while those prolapsing through the cervical os may be observed as pink, smooth-surfaced masses during vaginal examination.

Diagnosis and Differential Diagnosis

Diagnosis is usually straightforward based on the patient’s medical history, clinical manifestations, and imaging findings. Ultrasonography often differentiates uterine myomas from other pelvic masses, while contrast-enhanced ultrasound assists in identifying submucous myomas. Magnetic resonance imaging (MRI) accurately determines the size, number, and location of the myomas. Additional tools such as hysteroscopy, laparoscopy, or hysterosalpingography may be utilized for diagnostic confirmation if needed.

Uterine myomas should be differentiated from the following conditions:

Pregnant Uterus

Pregnant women typically have a history of missed periods and symptoms of early pregnancy. The uterus enlarges and softens consistent with gestational age. Pregnancy can be confirmed using urine or serum human chorionic gonadotropin (hCG) testing or ultrasonography.

Ovarian Tumors

In patients with ovarian tumors, menstrual changes are rare, and masses are usually localized to one side of the uterus. Differentiating solid ovarian tumors from pedunculated subserous myomas may be challenging, thus requiring imaging for confirmation. Diagnostic laparoscopy may be necessary for definitive identification.

Adenomyosis

Adenomyosis may present with uterine enlargement and menorrhagia. Focal adenomyosis resembles intramural myomas. Patients with adenomyosis often exhibit secondary dysmenorrhea and typically have uniform uterine enlargement. Imaging studies and peripheral blood CA125 testing may aid in diagnosis. It is important to recognize that uterine adenomyosis and myomas can coexist.

Malignant Uterine Tumors

These include:

- Uterine Sarcoma: Common in perimenopausal and elderly women, uterine sarcomas grow rapidly and are often accompanied by abdominal pain, abdominal masses, and irregular vaginal bleeding. Ultrasonography and MRI may assist in differentiation, but preoperative diagnosis is often difficult.

- Endometrial Cancer: Common in elderly women, postmenopausal vaginal bleeding is the primary symptom. The uterus may be uniformly enlarged or of normal size. Women with uterine myomas in the perimenopausal period should be evaluated for concurrent endometrial cancer. Imaging and endometrial biopsy aid in differential diagnosis.

- Cervical Cancer: Abnormal vaginal bleeding and increased vaginal discharge are common. Exophytic cervical cancer is easier to diagnose, while endophytic cervical cancer needs differentiation from cervical myomas. Imaging, cervical cytology, HPV testing, and cervical biopsy are helpful for diagnosis.

Other Conditions

Conditions such as endometriotic ovarian cysts, pelvic inflammatory masses, and uterine malformations need to be differentiated based on their history, clinical manifestations, and imaging findings (e.g., ultrasonography).

Treatment

Treatment should be tailored based on the patient’s age, clinical manifestations, reproductive desires, and the type, size, number, and location of the myomas, with an individualized treatment plan being developed.

Observation

Asymptomatic uterine myoma patients typically do not require treatment. Since many uterine myomas regress after menopause and symptoms may resolve, management in perimenopausal women should be approached comprehensively. Follow-ups are usually conducted every 3–6 months, and further treatment may be considered if symptoms develop.

Medical Treatment

This approach is suitable for symptomatic patients who are not candidates for surgery or for perimenopausal women. It may also be used preoperatively to manage anemia and other symptoms.

Gonadotropin-Releasing Hormone Agonists (GnRH-a)

These suppress pituitary secretion of FSH and LH, reducing estrogen levels to postmenopausal levels, thereby shrinking myomas and alleviating symptoms. However, the condition may recur after discontinuation. Indications include preoperative use to control symptoms, correct anemia, and reduce myoma size to ease surgery, or transition to menopause in perimenopausal women to avoid surgery. As these medications may induce menopausal symptoms, long-term use is not recommended.

Gonadotropin-Releasing Hormone Antagonists (GnRH-ant)

These also produce reversible and dose-dependent inhibition of gonadotropins and sex hormones, thereby achieving therapeutic effects. Compared to GnRH agonists, they do not cause the initial flare effect.

Selective Progesterone Receptor Modulators (SPRMs)

Drugs such as mifepristone can reduce myoma size and improve symptoms and may be used preoperatively or to expedite the transition to menopause. However, prolonged estrogen stimulation of the endometrium after progesterone antagonism may increase the risk of endometrial abnormalities. Therefore, long-term use is not advisable.

Sex Hormone-Based Medications

Combined oral contraceptives and the levonorgestrel-releasing intrauterine system (LNG-IUS) can relieve symptoms such as heavy menstrual bleeding but have limited effects on reducing myoma size. The World Health Organization has recommended using oral contraceptives for controlling excessive menstrual bleeding in women with uterine myomas.

Other Medications

Hemostatic agents such as tranexamic acid may help reduce excessive menstrual bleeding.

Nonsteroidal anti-inflammatory drugs (NSAIDs), such as ibuprofen or acetaminophen, can reduce prostaglandin synthesis by inhibiting cyclooxygenase, thereby alleviating dysmenorrhea and reducing menstrual blood loss.

Surgical Treatment

Surgery is the most effective treatment for uterine myomas. Indications for surgery include secondary anemia resulting from excessive menstrual bleeding, large myoma size, symptoms of pain or compression, impact on fertility, or suspicion of malignancy.

Types of surgical procedures include:

- Myomectomy: This is suitable for patients desiring to preserve fertility. Intramural and subserous myomas can be removed via laparotomy or laparoscopic myomectomy, while submucous myomas may be resected using hysteroscopic myomectomy. Submucous myomas protruding into the vaginal canal may be removed transvaginally. Residual or recurrent myomas may occur postoperatively, and it is necessary to completely remove the myomas during laparoscopic procedures to prevent seeding and implantation of tissue fragments. Malignant tissue fragmentation can lead to severe consequences.

- Hysterectomy: This is an option for patients with large, numerous myomas, significant symptoms, no desire for fertility, or suspected malignant transformation of the myoma. Total hysterectomy is typically performed, while subtotal hysterectomy is now rarely utilized. Preoperative evaluations should exclude cervical intraepithelial neoplasia, cervical cancer, and endometrial cancer. Intraoperative frozen section analysis is recommended if malignant transformation is suspected. Bilateral salpingectomy is often performed concurrently, and the decision regarding ovarian preservation depends on factors such as the patient’s age and family history.

Other Treatments

These are primarily intended for patients who cannot tolerate or do not wish to undergo surgery, but routine application is not recommended.

Uterine Artery Embolization (UAE)

This procedure reduces blood supply to the myomas by embolizing the uterine artery and its branches, slowing their growth and alleviating symptoms. There is a risk of ovarian function decline, making it less suitable for patients wishing to preserve fertility.

High-Intensity Focused Ultrasound (HIFU)

Myoma tissue is destroyed through the application of focused physical energy, leading to gradual absorption or scarring. However, residual and recurrent myomas are possible, and malignancy must be ruled out beforehand.

Uterine Myomas During Pregnancy

Ultrasound examination has shown that 3%–12% of pregnant women are affected by uterine myomas. Small and asymptomatic myomas are often overlooked, and the actual incidence rate is much higher than reported. The impact of uterine myomas on pregnancy and delivery is related to the anatomical changes they cause. Submucous myomas and large intramural myomas that extend towards the uterine cavity can impair implantation of the fertilized egg, leading to early miscarriage. Large intramural myomas may also deform the uterine cavity or compromise endometrial blood supply, resulting in pregnancy loss. Low-lying myomas can obstruct fetal descent, causing abnormal fetal positioning, placental abruption, or birth canal obstruction in late pregnancy or during childbirth. Postpartum hemorrhage may occur due to extensive placental attachment, difficulties with placental expulsion, or poor uterine contractility.

Red degeneration of uterine myomas is more common during pregnancy and the postpartum period, and conservative treatment often alleviates symptoms. Most pregnant women with uterine myomas can deliver vaginally, but precautions should be taken to prevent postpartum hemorrhage. Cesarean section may be required if myomas obstruct fetal descent, and the decision to simultaneously remove the myomas during surgery should be based on the size, location, and clinical situation of the patient.