Cervical cancer is the most common gynecological malignancy. The peak incidence of cervical cancer occurs at the age of 50–55 years, and in recent years there has been a trend toward younger age groups. The primary cause of cervical cancer is persistent infection with high-risk human papillomavirus (HPV). HPV vaccination can help prevent the occurrence of cervical cancer. Screening for cervical cancer is an effective method to detect precancerous lesions and early-stage cancers. Cervical cancer is a malignancy that is preventable, screenable, and treatable in its early stages and has the potential for elimination.

Associated Risk Factors

The main cause of cervical cancer is persistent infection with high-risk HPV. Other risk factors include having multiple sexual partners, immunosuppression, smoking, oral contraceptive use, and malnutrition.

Pathogenesis and Progression

The cervical transformation zone is the most common site of origin for cervical cancer. It is currently believed that cervical cancer develops through a process in which cervical epithelial cells undergo a series of quantitative and qualitative changes, transforming into malignancy. During the formation of the transformation zone, excessive metaplasia of cervical squamous epithelium occurs. When risk factors persist—such as the integration of HPV oncogenes into the DNA of cervical epithelial cells—this can lead to persistent infection, immune suppression, and the degradation or inactivation of p53 and Rb proteins. Immature or hyperplastic metaplastic squamous epithelium can then exhibit anaplasia or atypical changes, leading to varying degrees of dysplasia or impaired differentiation, cellular disarray, nuclear atypia, and increased mitotic activity, forming cervical intraepithelial neoplasia (CIN). As CIN progresses, it can breach the epithelial basement membrane, invade the stroma, and develop into invasive cervical cancer.

Pathology

Gross Features

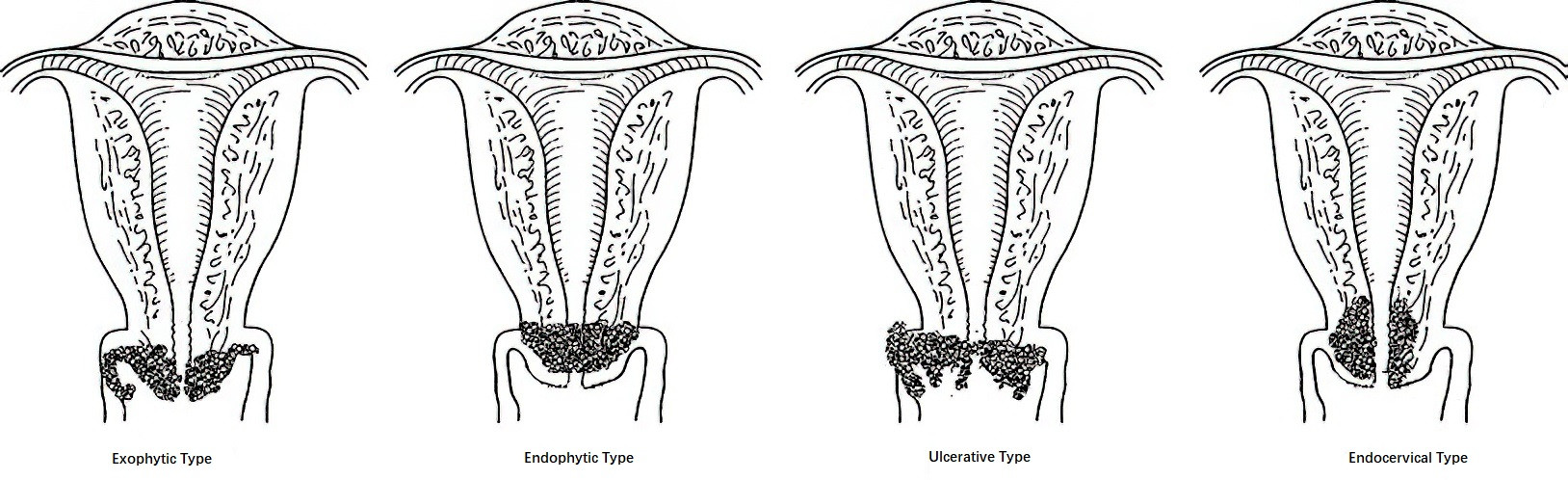

In the earliest stages of invasive cervical cancer, visible abnormalities may not be apparent. As the disease progresses, four morphological types may develop:

- Exophytic Type: This is the most common type, in which the tumor grows outward and appears as papillary or cauliflower-like formations. The tissue is friable, prone to bleeding, and often involves the vagina.

- Endophytic Type: The tumor infiltrates the deeper tissues of the cervix, resulting in a smooth surface or slight columnar epithelial ectopy. The cervix becomes enlarged, firm, and barrel-shaped, often involving the parametrium.

- Ulcerative Type: This represents further progression of the exophytic and endophytic types, with infection and necrosis leading to tissue shedding and the formation of ulcers or cavities resembling a volcanic crater.

- Endocervical Type: The tumor originates within the cervical canal, with minimal external change, making it prone to missed diagnoses. It often invades the lower uterine segment.

Figure 1 Types of cervical cancer (Gross appearance)

Histology

Cervical Squamous Cell Carcinoma (SCC)

This accounts for 75–85% of cervical cancer cases and most commonly arises at the squamocolumnar junction. Based on association with HPV infection, it can be categorized as HPV-associated or HPV-independent.

- Microinvasive Carcinoma: Refers to tumor cells that breach the basement membrane and exhibit droplet-like or serrated infiltration into the stroma, with a depth of no more than 5 mm, based on a background of high-grade squamous intraepithelial lesions.

- Invasive Carcinoma: Refers to tumor cells invading beyond the microinvasive threshold into the stroma. This type is further classified based on the degree of cell differentiation into keratinizing squamous cell carcinoma and non-keratinizing squamous cell carcinoma. Keratinizing carcinoma forms keratin pearls, with cells characterized by large size, abundant cytoplasm (clear or eosinophilic), and diverse nuclear shapes. Non-keratinizing carcinoma is more common and consists mainly of polygonal squamous cells with clear boundaries, growing in sheets or nests. Cell bridges may be present, but keratin pearls are absent. In higher-grade tumors, nuclear polymorphism is more pronounced, with abundant mitotic activity, unevenly distributed, coarse, granular chromatin, and prominent nucleoli.

Cervical Adenocarcinoma

This accounts for 15–20% of cervical cancer cases and has shown an increasing incidence in recent years. While most cervical adenocarcinomas are related to high-risk HPV infection, approximately 15% are HPV-independent. This type is further classified as HPV-associated or HPV-independent. Based on glandular differentiation, adenocarcinomas are divided into well-differentiated, moderately differentiated, and poorly differentiated types.

HPV-associated adenocarcinomas include the usual type and mucinous type, with the usual type being the most common, accounting for 75–80% of all cervical adenocarcinomas. These tumors consist of densely packed, irregularly arranged glands lined by columnar cells. The nuclei exhibit moderate to severe atypia, with numerous mitotic figures on the luminal side and apoptotic bodies at the basal side. Tumors with significant mucinous differentiation are classified as mucinous cervical adenocarcinomas.

HPV-independent cervical adenocarcinomas include gastric-type adenocarcinoma, clear cell carcinoma, mesonephric adenocarcinoma, and endometrioid carcinoma. Gastric-type adenocarcinoma features well-defined cell borders, abundant cytoplasm containing neutral mucin, and differentiation ranging from well-differentiated (formerly referred to as minimal deviation adenocarcinoma) to poorly differentiated forms. Poorly differentiated forms exhibit nuclear variability and foamy appearance with prominent nucleoli. Gastric-type adenocarcinomas are highly invasive and have a poor prognosis.

Adenosquamous Carcinoma

This is rare, accounting for 3–5% of cervical cancers. It arises from reserve cells in the cervical canal, which differentiate into both adenocarcinoma and squamous cell carcinoma. The tumor contains both glandular and squamous components, with varying proportions and differentiation levels of each. Poorly differentiated types are associated with worse outcomes.

Other Types

This category includes neuroendocrine carcinoma and carcinosarcoma, both of which are associated with extremely poor prognoses.

Metastatic Pathways

The primary pathways of metastasis include direct extension and lymphatic spread, while hematogenous spread is rare.

Direct Extension

Direct extension is the most common pathway of metastasis, involving the spread of the tumor to adjacent organs and tissues. The tumor may extend downward to involve the vaginal wall, upward through the cervical canal to the uterine body, and laterally to the cardinal ligaments, parametrium, paravaginal tissues, and pelvic wall. In advanced stages, the tumor can spread anteriorly or posteriorly to invade the bladder or rectum, leading to conditions such as vesicovaginal or rectovaginal fistulas. Compression or invasion of the ureters by the tumor may result in ureteral obstruction and hydronephrosis.

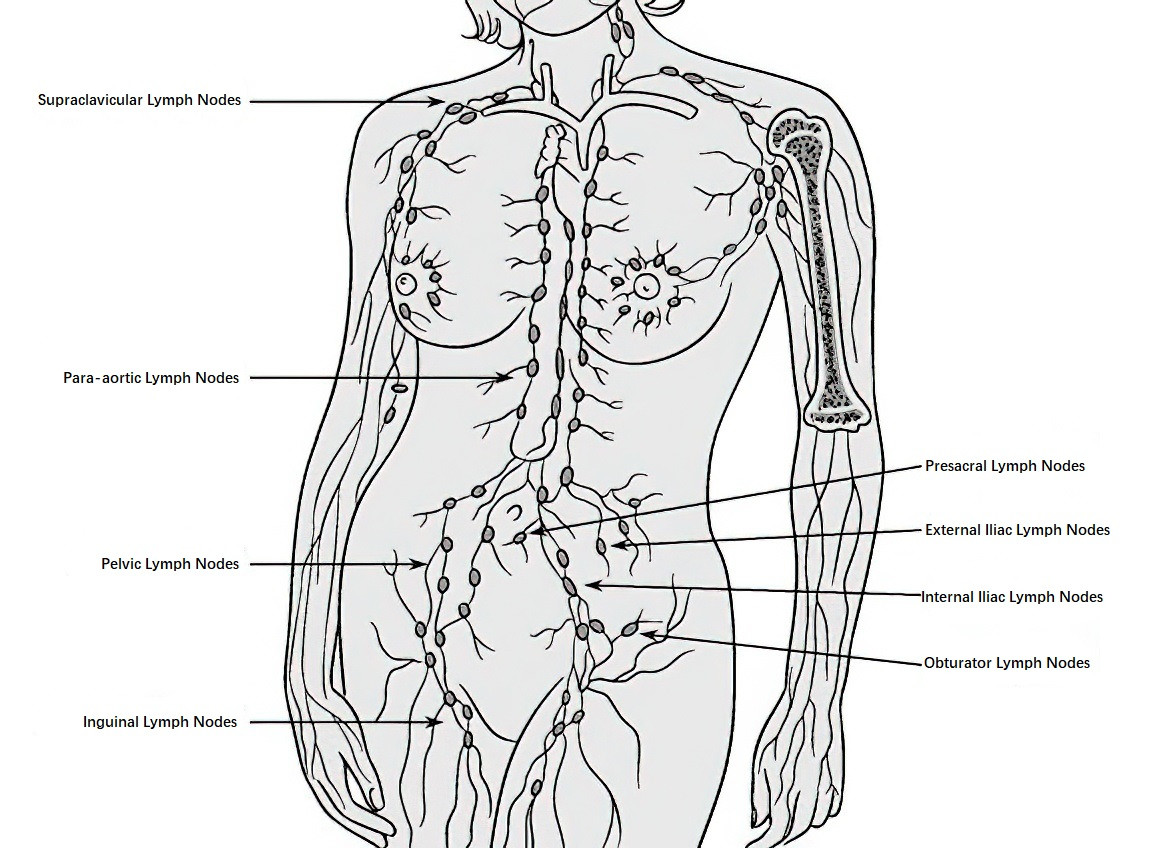

Lymphatic Spread

After local invasion, the tumor may involve lymphatic vessels and spread through lymphatic drainage to local lymph nodes. The primary groups of lymph nodes affected include pelvic lymph nodes, such as the parametrial, paracervical, obturator, internal iliac, external iliac, common iliac, and presacral lymph nodes. Secondary lymphatic groups include para-aortic and inguinal lymph nodes, with distant spread possibly involving mediastinal and supraclavicular lymph nodes. In recent years, the application of sentinel lymph nodes (SLNs) has become increasingly common. Sentinel lymph nodes refer to one or more lymph nodes that first receive drainage from the tumor. The status of SLNs reflects the condition of the entire lymphatic drainage basin. If SLNs are confirmed to be free of metastasis, systemic lymphadenectomy may not be necessary. Sentinel lymph nodes can be visualized by injecting dyes, such as indocyanine green (ICG), or radiotracers, such as technetium-99m (99mTc), directly into the cervix. ICG can be observed intraoperatively using a fluorescence laparoscope, whereas radiotracers require a gamma-ray detection device. Internationally, ICG is the most widely used and validated tracer. For institutions without fluorescence laparoscopes, nano-carbon tracers may serve as an alternative.

Figure 2 Schematic diagram of cervical cancer lymphatic metastasis

Hematogenous Spread

Hematogenous metastasis is extremely rare but can occur in advanced cases, with metastatic sites including the lungs, liver, and bones.

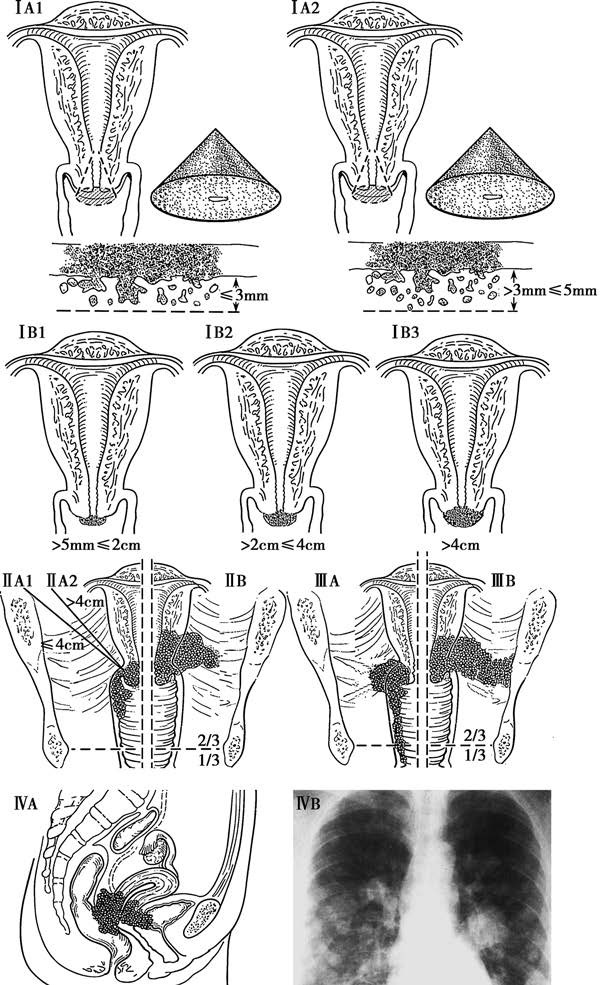

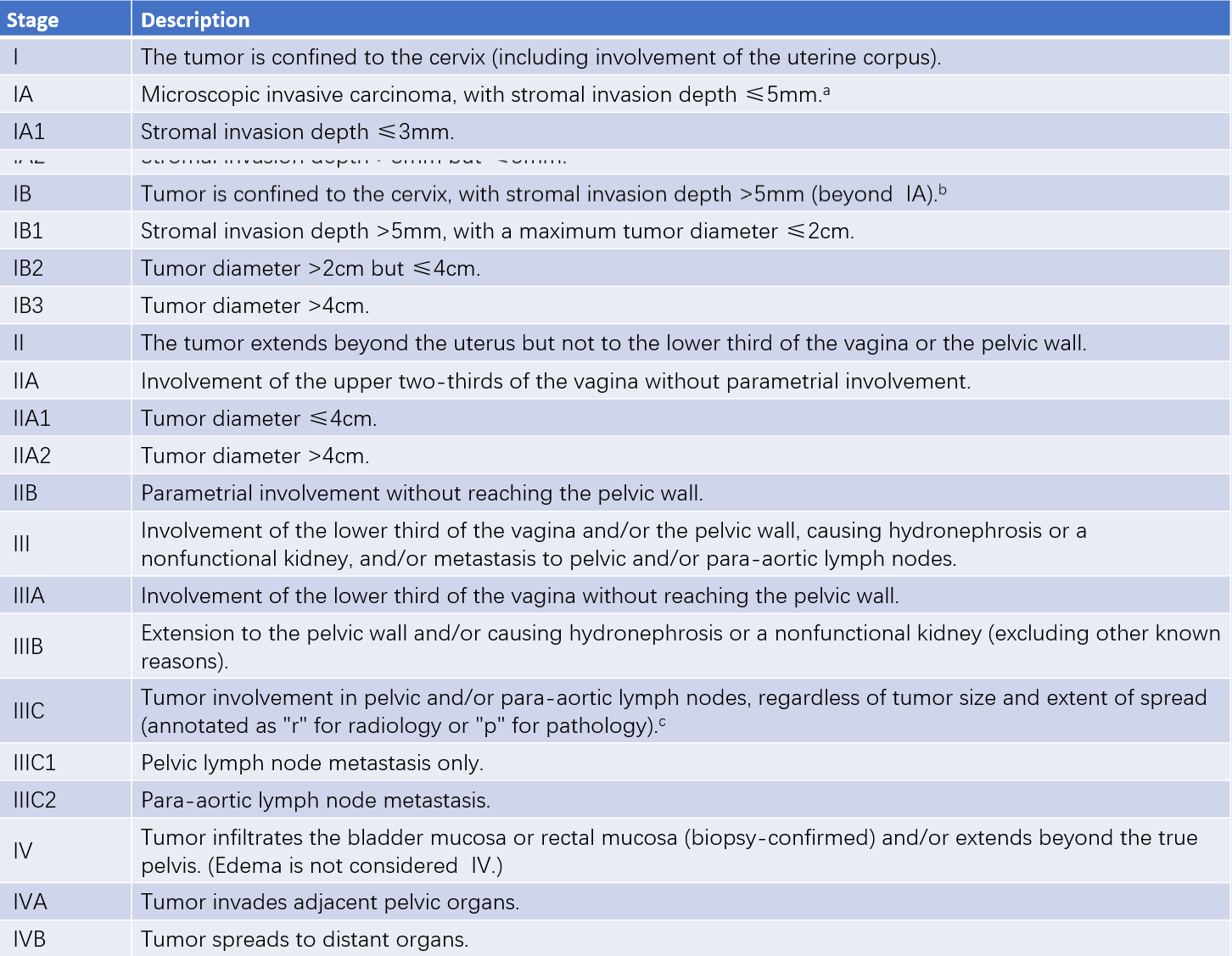

Staging

The 2018 staging system of the International Federation of Gynecology and Obstetrics (FIGO) is used to classify cervical cancer. Staging can change before and after initial treatment; however, recurrence or metastasis is not staged again.

Figure 3 Staging of cervical cancer

Table 1 Staging of cervical cancer (FIGO, 2018)

Notes:

In cases of uncertainty, the lower stage should be assigned.

a, Staging can be supplemented with imaging and pathological findings to assess tumor size and extent of spread for determining the final stage.

b, Lymphovascular space invasion does not alter staging, and the width of invasion is no longer a staging criterion.

c, For evidence supporting Stage IIIC, the method of determination (r for imaging or p for pathology) needs to be specified. For example, if imaging shows pelvic lymph node metastasis, the stage is assigned as IIIC1r. If confirmed by pathology, it is IIIC1p. The type of imaging or pathological technique used should also be noted.

Clinical Manifestations

Early cervical cancer may present without significant symptoms or signs. Patients with endocervical-type tumors may have a normal cervical appearance, making diagnosis more challenging. As the disease progresses, the following features may become apparent:

Symptoms

Vaginal Bleeding

Vaginal bleeding may present as postcoital bleeding, occurring after sexual intercourse or gynecological examinations. It may also manifest as irregular vaginal bleeding, prolonged menstrual periods, or increased menstrual flow. In postmenopausal women, irregular vaginal bleeding is common. The volume of bleeding depends on the size of the lesion and the extent of stromal vascular involvement; erosion of large blood vessels can result in massive hemorrhage. Exophytic tumors typically cause early and heavier bleeding, while endophytic tumors result in delayed bleeding.

Increased Vaginal Discharge

A significant proportion of patients may experience increased vaginal discharge. The discharge may appear watery, blood-tinged, or white, with a foul odor. In advanced cases, tumor necrosis and infection may lead to a large volume of rice-water-like or purulent discharge with a strong malodor.

Late Symptoms

Secondary symptoms arise depending on the extent and location of tumor involvement. These include urinary frequency, urgency, constipation, and swelling and pain in the lower limbs. Compression or involvement of the ureters by the tumor may lead to ureteral obstruction, hydronephrosis, and uremia. Systemic symptoms such as anemia, cachexia, and general debilitation are associated with advanced disease.

Signs

Microinvasive cervical cancer may not produce visible lesions, with the cervix appearing smooth or showing erosive changes. As the disease progresses, different clinical signs may develop:

- Exophytic Cervical Cancer: Polypoid or cauliflower-like growths that are often accompanied by infection. The tissue is friable and prone to bleeding.

- Endophytic Cervical Cancer: The cervix appears enlarged, firm, and barrel-shaped. In severe cases, the cervix may become grossly thickened.

In advanced stages, necrosis and tissue sloughing may cause the formation of ulcers or cavities with a foul odor.

When the vaginal wall is involved, vegetative growth or hardening may be observed.

Parametrial involvement may present as thickened, nodular, and firm tissues upon bimanual or rectovaginal examination. Severe cases can lead to a "frozen pelvis" appearance, where pelvic structures are completely immobile.

Diagnosis

The diagnosis is based on the patient's medical history and clinical manifestations, with particular attention given to individuals presenting with contact bleeding. A preliminary judgment can typically be made through standardized gynecological examinations. Suspicious cervical lesions should follow a "three-step" diagnostic procedure, which includes HPV testing (the preferred method for initial screening) and cervical cytology. If abnormalities are detected, colposcopy is recommended. For lesions presenting with prominent vegetations or ulceration, a biopsy can be performed directly to establish a definitive diagnosis. Once a pathological diagnosis is confirmed, appropriate imaging examinations should be selected based on the patient's specific condition to assess the extent of tumor spread.

Colposcopy

This can be seen in the diagnostic approach used for "cervical intraepithelial neoplasia."

Cervical and Endocervical Biopsy

This serves as the basis for the definitive diagnosis of cervical intraepithelial lesions and cervical cancer. For apparent cervical lesions, tissue samples can be taken directly from the lesion site. If cervical lesions appear inconspicuous, the acetowhite staining and iodine staining methods may be employed sequentially.

Acetowhite Test

A 3–5% acetic acid solution is applied to the cervical surface. Abnormal epithelial cells, especially those of intraepithelial lesions, undergo enhanced protein coagulation, appearing opaque and white, a phenomenon known as the acetowhite effect.

Iodine Test

An iodine solution is applied to the cervical surface. Normal squamous epithelium of the cervical ectocervix, rich in glycogen, stains brown or dark brown after application. Areas that fail to stain lack glycogen and may indicate inflammatory or other pathological regions. Biopsy samples taken from acetowhite-positive or iodine-negative areas can improve diagnostic accuracy. Tissues taken should include some stroma and adjacent normal tissues. If endocervical lesions are suspected, endocervical curettage should additionally be performed, and the tissue sent for pathological examination.

Cervical Conization

Cervical conization serves both diagnostic and therapeutic purposes. Indications include persistent positive cervical cytology results with negative biopsies or cases where a high-grade squamous intraepithelial lesion (HSIL) is detected but invasive cancer cannot be ruled out. Tissue samples from cervical conization should be sent for histopathological examination. Cervical conization may be performed using cold knife conization (CKC) or loop electrosurgical excision procedures (LEEP). The cone biopsy specimen should undergo serial pathological sectioning for examination.

Imaging Examinations

After confirmation by pathological examination, imaging studies are selected based on the patient's condition to evaluate the extent of the disease. These may include chest X-ray, ultrasound, computed tomography (CT), magnetic resonance imaging (MRI), positron emission tomography/computed tomography (PET/CT), intravenous pyelography, cystoscopy, and rectoscopy.

Differential Diagnosis

Cervical cancer must be differentiated from various cervical lesions with similar clinical symptoms or signs, with histopathological diagnosis serving as the primary distinguishing criterion. These include:

- Benign Cervical Lesions: Such as cervical columnar epithelium ectopia, cervical polyps, cervical endometriosis, cervical glandular epithelium ectopia, and tuberculous cervical ulcers.

- Benign Cervical Tumors: Such as cervical fibroids and cervical papillomas.

- Metastatic Cervical Tumors: Including non-Hodgkin lymphoma of the cervix and cervical metastases of endometrial cancer. Additionally, it is important to recognize that primary cervical cancer and endometrial cancer may coexist.

Treatment

The treatment plan considers clinical staging, patient age, fertility preservation needs, general condition, medical expertise, and technological resources. Treatment methods include surgery, radiotherapy, chemotherapy, targeted therapy, and immunotherapy. Early-stage cervical cancer is primarily treated with surgery, while advanced stages are predominantly managed with chemoradiotherapy. Treatment is individualized based on the patient's specific circumstances.

Surgical Treatment

Surgical treatment is mainly used for early-stage patients (stages IA–IIA1). Its advantages include preserving ovarian and vaginal function in young patients, thus improving post-treatment quality of life.

- Stage IA1: In cases without lymphovascular space invasion (LVSI) and no fertility preservation requirements, extrafascial hysterectomy is an option, with cervical conization recommended preoperatively to better determine the extent of the lesion and stage. For fertility preservation, cervical conization can be performed, with pathological evaluation ensuring clear resection margins. Cases with LVSI are treated as stage IA2.

- Stage IA2: Patients without fertility requirements undergo modified radical hysterectomy with pelvic lymph node assessment. For fertility preservation, radical trachelectomy with pelvic lymph node assessment is preferred, although cervical conization with pelvic lymph node assessment may also be considered, provided resection margins are clear.

- Stages IB1, IB2, and IIA1: Treatment involves radical hysterectomy with pelvic lymphadenectomy and selective para-aortic lymphadenectomy. For patients with fertility requirements at stage IB1, radical trachelectomy with pelvic lymph node assessment and selective para-aortic lymphadenectomy is recommended. Sentinel lymph node biopsy may be used to replace systemic lymphadenectomy in cases where the tumor size is <2 cm.

Radiotherapy

Radiotherapy includes:

- Definitive Radiotherapy: Applied to some IB3, IIA2, and more advanced stages, or for patients unsuitable for surgery. This typically involves brachytherapy and external beam radiotherapy. Brachytherapy uses sources such as cesium-137 (137Cs) or iridium-192 (192Ir), while external beam radiotherapy often utilizes linear accelerators or cobalt-60 (60Co). Brachytherapy controls the primary tumor, while external beam radiotherapy addresses parametrium and pelvic metastases.

- Adjuvant Radiotherapy: Necessary for patients with moderate- to high-risk factors following surgery.

- Palliative Radiotherapy: Used for symptom relief in advanced, recurrent, or metastatic cases.

It is important to note that radiotherapy significantly damages ovarian function and impairs vaginal elasticity and secretion. Given the increasing incidence of cervical cancer in younger patients, early-stage cases are generally managed without radiotherapy as the first-line treatment. For cases requiring radiotherapy, ovarian transposition to the paracolic gutters of the upper abdomen is recommended during surgery, with ovarian shielding using lead plates during irradiation to minimize ovarian damage.

Chemotherapy

Chemotherapy includes:

- Concurrent Chemoradiotherapy: Referring to chemotherapy administered alongside radiotherapy, this approach can be used for definitive treatment or as adjuvant therapy. Platinum-based concurrent chemoradiotherapy has been shown to significantly reduce recurrence and mortality risks in advanced cervical cancer compared to radiotherapy alone, thereby extending survival. For patients with positive pelvic lymph nodes, parametrial invasion, or positive surgical margins, pelvic external beam radiotherapy plus concurrent cisplatin chemotherapy ± vaginal brachytherapy is recommended. Vaginal margin positivity requires additional vaginal brachytherapy with concurrent chemotherapy.

- Neoadjuvant Chemotherapy: Used for locally advanced cervical cancer with lesions ≥4 cm to reduce tumor size and facilitate surgical resection. However, the value of neoadjuvant chemotherapy in cervical cancer remains controversial internationally.

- Chemotherapy for Advanced or Recurrent Cancer: Chemotherapy may serve as first-line treatment for advanced or recurrent cancers, as well as second-line or palliative treatment. Common drugs include cisplatin, carboplatin, paclitaxel, topotecan, irinotecan, and gemcitabine. Cisplatin is the preferred platinum-based agent, while carboplatin is an alternative for patients intolerant to cisplatin. Frequently used regimens include cisplatin (as a radiosensitizer), cisplatin/carboplatin with paclitaxel, cisplatin with topotecan, and cisplatin with gemcitabine.

Targeted Therapy and Immunotherapy

For advanced, metastatic, or recurrent cervical cancer, the addition of bevacizumab to platinum-based chemotherapy significantly extends survival.

In recent years, studies have demonstrated that immune checkpoint inhibitors are effective not only as second-line treatments for recurrent cervical cancer following platinum failure but also when used in first-line regimens for metastatic or recurrent cases. Their use has also shown potential in concurrent definitive chemoradiotherapy for high-risk locally advanced cervical cancer.

Several immune checkpoint inhibitors have been approved for second-line treatment of advanced, metastatic, or recurrent cervical cancer. These include monoclonal antibodies targeting programmed death protein-1 (PD-1), programmed death-ligand 1 (PD-L1), and dual-specific antibodies targeting both cytotoxic T-lymphocyte-associated protein 4 (CTLA-4) and PD-1.

Prognosis

The prognosis is closely related to clinical stage, pathological type, and treatment method. For stages IB and IIA, the outcomes of surgery and radiotherapy are similar; however, recent clinical studies suggest that surgery has better efficacy than radiotherapy. Radiotherapy is less effective for cervical adenocarcinoma compared to squamous cell carcinoma, and early lymphatic metastasis in these cases often leads to a poorer prognosis. Factors such as tumor differentiation, positive surgical margins, lymphovascular space invasion, and the location and extent of lymphatic metastases also impact prognosis. Patients showing these adverse features in postoperative pathology may require appropriate adjuvant therapy. Common causes of death in advanced cervical cancer include uremia, hemorrhage, infection, and cachexia. Prognosis for small cell cervical cancer is particularly poor, although standardized and aggressive treatment can improve survival rates.

Follow-Up

After completing treatment for cervical cancer, follow-up should occur every 3 to 6 months during the first 2 years, every 6 to 12 months from years 3 to 5, and annually starting from the 6th year. For high-risk cervical cancer patients, such as those with immunodeficiency, follow-up is recommended every 3 months in the first 2 years and every 6 months from years 3 to 5. Follow-up may include gynecological examination, high-risk HPV testing, vaginal cytology (or cervical cytology for patients retaining their cervix), serum tumor markers (e.g., squamous cell carcinoma antigen), and imaging studies.

Prevention

Cervical cancer is a preventable malignancy. Public health education should be enhanced to promote awareness of cervical cancer prevention. HPV vaccination, as a primary prevention measure, can prevent cervical cancer by blocking HPV infection, particularly in adolescent females. Standardized cervical cancer screening enables early detection and diagnosis, representing secondary prevention. Proper treatment improves patient survival and quality of life, constituting tertiary prevention. Through collective societal efforts, the elimination of cervical cancer as a public health problem may become an attainable goal by the 21st century.

Cervical Cancer During Pregnancy

Cervical cancer during pregnancy is rare. Women who have not undergone routine screening before pregnancy should undergo HPV testing or cervical cytology during pregnancy. For pregnant women presenting with vaginal bleeding, gynecological examination should follow exclusion of obstetric causes. If suspicious cervical lesions are identified, HPV testing, cervical cytology, colposcopy, and, where necessary, biopsy under colposcopic guidance are conducted for definitive diagnosis. Since cervical conization may lead to late miscarriage and preterm birth, diagnostic cervical conization is only considered when cytology and histopathology strongly suggest invasive cervical cancer and a biopsy fails to confirm it.

Management depends on the stage of cervical cancer, gestational age, and the patient's desire to maintain the pregnancy. If cervical cancer is diagnosed before 22 weeks of pregnancy, observation may be appropriate for stage IA1 cases, while termination of pregnancy is generally recommended for other stages. Cervical cancer diagnosed between 22 and 28 weeks allows chemotherapy for patients up to stage IB2. Treatment delay is generally not recommended for patients in stage IB3 or higher. For cervical cancer diagnosed after 28 weeks, delivery via cesarean section at 34 weeks with concurrent radical surgery may be undertaken if the fetus has reached viability. Advanced-stage patients may undergo radiotherapy or chemotherapy after cesarean delivery.