Stress urinary incontinence (SUI) refers to the involuntary leakage of urine caused by a sudden increase in intra-abdominal pressure, without being linked to detrusor contractions or bladder wall tension during urine storage. It is characterized by the absence of urinary leakage under normal conditions, with urine escaping involuntarily when intra-abdominal pressure increases. This type of incontinence is also known as true stress incontinence, tension incontinence, or exertional urinary incontinence.

Etiology

Stress urinary incontinence can be divided into two types. Over 90% of cases are anatomical stress urinary incontinence, primarily caused by pelvic floor tissue relaxation. Factors contributing to the relaxation of pelvic floor tissues include pregnancy and vaginal delivery-related trauma, as well as decreased estrogen levels after menopause. The widely accepted "pressure transmission theory" suggests that the cause of stress urinary incontinence lies in defects of pelvic floor support structures, leading to the descent of the bladder neck and proximal urethra below the pelvic floor. As a result, intra-abdominal pressure during coughing does not evenly transmit to the bladder and the proximal urethra, causing bladder pressure to exceed urethral pressure and resulting in leakage. Fewer than 10% of cases involve intrinsic sphincter deficiency (ISD), which is usually due to congenital abnormalities.

Clinical Presentation

Most lower urinary tract symptoms and several vaginal symptoms can occur with stress urinary incontinence. The most characteristic symptom is involuntary urine leakage during increases in intra-abdominal pressure. Common accompanying symptoms include urinary urgency, frequency, urge incontinence, and a sensation of bladder fullness after voiding. Approximately 80% of patients with stress urinary incontinence also present with anterior vaginal wall prolapse (cystocele).

Severity Grading

The severity of stress urinary incontinence can be classified subjectively or objectively. Objective grading often uses pad tests, but clinical practice commonly adopts simple subjective grading:

- Grade I: Leakage occurs only under significant increases in intra-abdominal pressure, such as during coughing, sneezing, or jogging.

- Grade II: Leakage occurs under moderate increases in intra-abdominal pressure, such as during rapid movements or climbing stairs.

- Grade III: Leakage occurs under mild increases in intra-abdominal pressure; the patient can control urine in a supine position but experiences involuntary leakage upon standing.

Diagnosis

There is no single diagnostic test for stress urinary incontinence. Diagnosis is primarily based on the patient's symptoms. In addition to routine physical, gynecological, and neurological examinations, auxiliary tests such as stress tests, Bonney tests, Q-tip tests, and urodynamic studies are used to rule out urgency incontinence, overflow incontinence, and infections.

Stress Test

The patient assumes the lithotomy position with a full bladder. During coughing, the examiner observes the external urethral meatus. Repeated urinary leakage with each cough suggests SUI. Delayed leakage or large volumes of urine suggest uninhibited bladder contractions. If no urine leakage is observed in the lithotomy position, the stress test may be repeated in the standing position.

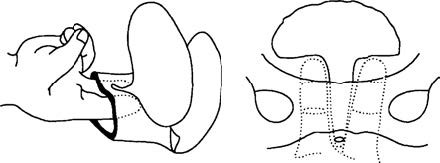

Bonney Test

The examiner places the index and middle fingers inside the anterior vaginal wall on either side of the urethra, with the fingertips positioned at the junction of the bladder and urethra. By elevating the bladder neck and repeating the stress test, the disappearance of SUI indicates a positive test result.

Figure 1 Diagram of the Bonney test

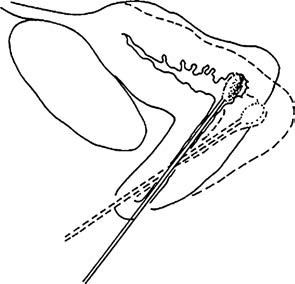

Q-tip Test

With the patient in a supine position, a Q-tip coated with lidocaine gel is inserted into the urethra until the tip reaches the urethrovesical junction. The angle formed between the Q-tip and the ground is measured during rest and during a Valsalva maneuver (forced exhalation against a closed glottis).

- A difference of less than 15° suggests good anatomical support.

- A difference greater than 30° indicates weak anatomical support.

- A difference between 15° and 30° yields indeterminate results.

Figure 2 Diagram of the Q-tip test

Urodynamic Studies

These include cystometry and uroflowmetry. Cystometry assesses detrusor reflexes and the patient's ability to control or suppress these reflexes. It helps differentiate between incontinence caused by uninhibited detrusor contractions and SUI. Uroflowmetry evaluates the speed and completeness of bladder emptying.

Cystoscopy and Ultrasound

These imaging modalities may assist in the diagnosis.

Differential Diagnosis

Urgency urinary incontinence is the most common condition that must be differentiated from stress urinary incontinence, as overlapping symptoms and signs are frequently observed. Urodynamic studies are particularly useful in distinguishing between these two conditions.

Treatment

Non-Surgical Treatment

Non-surgical treatment is suitable for mild to moderate stress urinary incontinence and as an adjunct therapy before and after surgical intervention. Non-surgical approaches include pelvic floor muscle exercises, pelvic floor electrical stimulation, α-adrenoceptor agonists, and local vaginal estrogen therapy. Approximately 30%–60% of patients experience symptom improvement, and some cases of mild stress urinary incontinence can be cured through non-surgical treatment. Postpartum pelvic floor muscle exercises are beneficial for women experiencing postpartum urinary incontinence.

Surgical Treatment

There are over 100 surgical procedures for stress urinary incontinence. Currently, the most widely recognized effective surgical techniques are the retropubic bladder neck suspension and the mid-urethral sling procedure. Because the mid-urethral sling is minimally invasive, it has become the most commonly performed surgery. Surgical treatment for stress urinary incontinence is generally recommended after the patient has completed childbearing.

Retropubic Bladder Neck Suspension

This procedure involves suturing the fascia on both sides of the bladder neck and proximal urethra to the pubic symphysis (Marshall-Marchetti-Krantz surgery) or to the Cooper's ligament (Burch colposuspension) in the retropubic (Retzius) space, thereby increasing the angle at the bladder-urethral junction.

Burch colposuspension is the most widely performed technique and can be completed using open surgery, laparoscopy, or the "suture-passer" method. It is suitable for anatomical stress urinary incontinence. The one-year post-operative cure rate is 85%–90%, although this may decline slightly over time.

Mid-Urethral Sling Procedure

In addition to treating anatomical stress urinary incontinence, this procedure is also indicated for intrinsic sphincter deficiency and mixed incontinence (a combination of stress and urgency urinary incontinence). The sling can be made from autologous fascia or non-absorbable synthetic materials. Currently, polypropylene sling materials are more widely used and have become a first-line treatment. The one-year post-operative cure rate is approximately 90%, and studies with follow-up periods as long as 11 years show cure rates exceeding 70%.

The anterior vaginal wall repair technique (e.g., Kelly plication) was once considered a simple surgical option. This procedure involves folding and suturing the fascia near the bladder neck to increase bladder-urethral resistance. Although it was historically a major surgical technique for stress urinary incontinence, its anatomical and clinical outcomes are inferior, with a one-year cure rate of only around 30%, which declines significantly over time. It is no longer considered an effective treatment for stress urinary incontinence.

Prevention

Prevention measures are similar to those for pelvic organ prolapse.