The pelvic floor support system, composed of a complex network of muscles, fascia, ligaments, and nerves, works together to maintain the normal positioning of pelvic organs. Pelvic floor dysfunction (PFD), also known as pelvic floor defects or relaxation of pelvic supports, results from weakened pelvic floor support caused by various factors, leading to the displacement of pelvic organs and associated abnormalities in their position and function.

Pelvic organ prolapse (POP) refers to the descent of pelvic organs into or outside the vaginal canal. In 2001, the National Institutes of Health (NIH) defined POP as any segment of the vaginal wall reaching or descending 1 cm beyond the hymenal ring. While it can occur in isolation, it most often involves multiple compartments simultaneously.

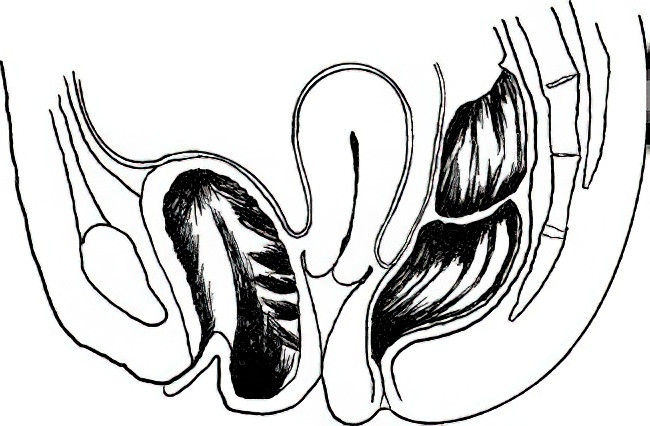

Anterior vaginal wall prolapse, also referred to as anterior vaginal wall descent, is categorized based on the affected area. When the upper two-thirds of the anterior vaginal wall adjacent to the bladder descends, it is called a cystocele. If damage to the pubocervical fascia, which supports the urethra, is severe, the lower one-third of the anterior vaginal wall adjacent to the urethra may protrude downward with the external urethral orifice as the pivot point. This is referred to as a urethrocele.

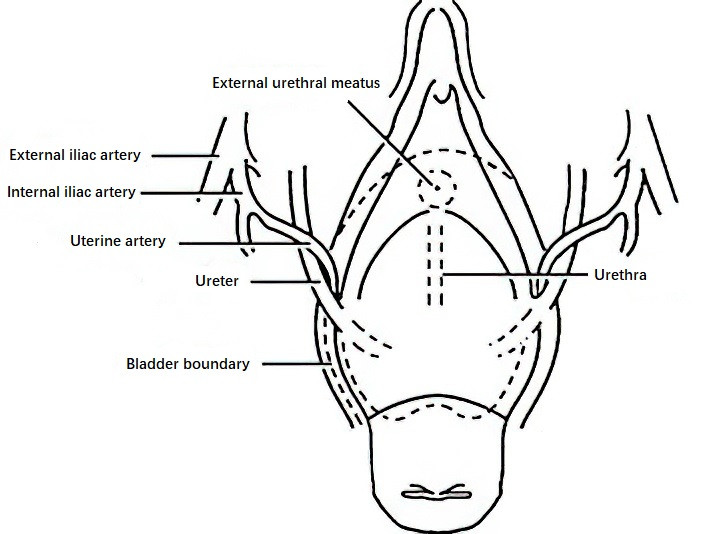

Figure 1 Diagram illustrating anterior vaginal wall prolapse (cystocele)

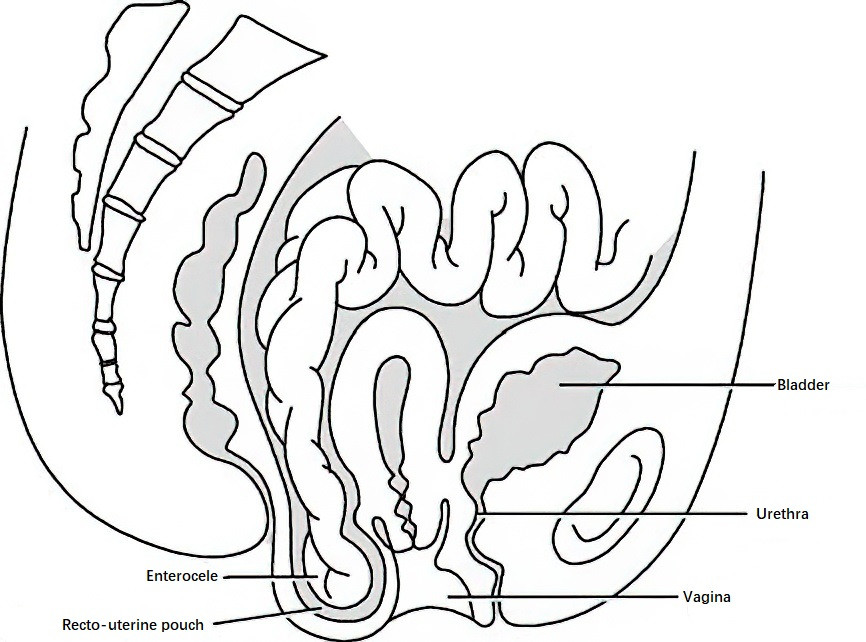

Posterior vaginal wall prolapse, also known as rectocele, often occurs in conjunction with an enterocele involving the rectouterine pouch. If the contents of the prolapsed pouch include bowel loops, it is referred to as an enterocele.

Figure 2 Diagram illustrating posterior vaginal wall prolapse (rectocele)

Figure 3 Diagram illustrating enterocele

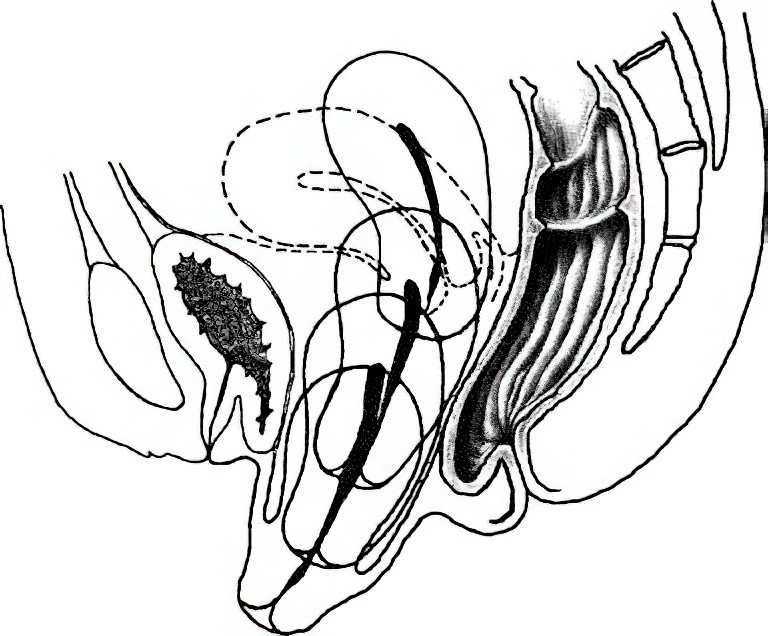

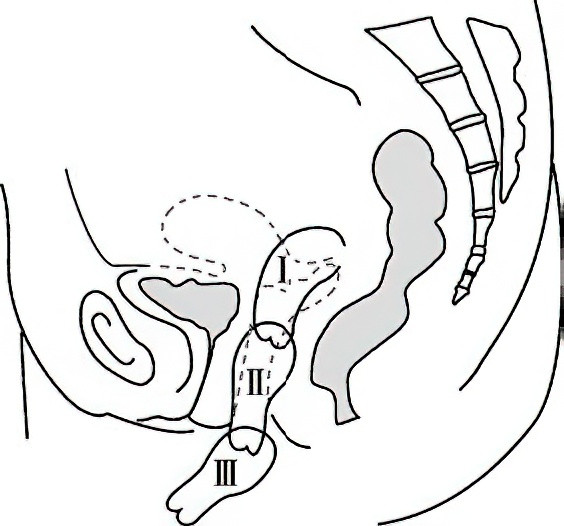

Uterine prolapse occurs when the uterus descends from its normal position along the vaginal canal, with the external cervical os falling below the level of the ischial spines or, in severe cases, the entire uterus protruding beyond the vaginal introitus.

Figure 4 Diagram illustrating uterine prolapse

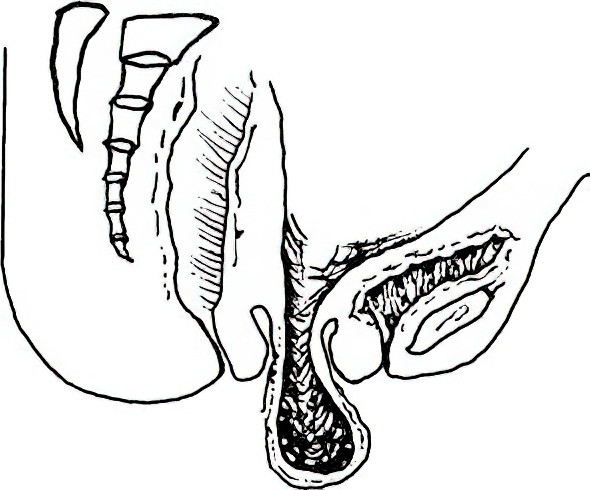

Vaginal vault prolapse may develop following a hysterectomy if the supportive structures of the vaginal apex are compromised.

Figure 5 Diagram illustrating vaginal vault prolapse

Etiology

Pregnancy and Childbirth

Vaginal deliveries, particularly those involving instrumental interventions like forceps or vacuum extraction, may weaken the supportive mechanisms of the pelvic fascia, ligaments, and muscles due to overstretching. Premature engagement in physical activities, especially heavy labor postpartum, can impair the recovery of tension within the pelvic floor and lead to pelvic organ prolapse.

Aging

Supporting structures may undergo atrophy with advancing age, particularly after menopause, and play a significant role in the onset and progression of pelvic floor relaxation.

Increased Intra-abdominal Pressure

Chronic coughing, abdominal ascites, central obesity, persistent heavy lifting, or constipation can increase intra-abdominal pressure, contributing to pelvic organ prolapse.

Iatrogenic Factors

Post-surgical failure to fully correct defects in the pelvic floor support structure can also cause prolapse.

Clinical Presentation

Symptoms

Mild cases are often asymptomatic. Advanced prolapse may result in ligament and fascial tension as well as pelvic congestion, causing varying degrees of lumbosacral discomfort or a dragging sensation in the pelvis. Symptoms typically worsen with prolonged standing or physical exertion and improve with bed rest.

Anterior vaginal wall prolapse is frequently associated with urinary symptoms, such as frequent urination, difficulty voiding, increased post-void residual, and, in some cases, stress urinary incontinence. Interestingly, stress urinary incontinence may resolve as the extent of the prolapse increases, and some patients may need to manually compress the anterior vaginal wall to facilitate voiding. This condition can also lead to recurrent urinary tract infections.

Posterior vaginal wall prolapse is often accompanied by constipation, with some patients requiring manual compression of the posterior vaginal wall to aid defecation.

In cases of pelvic organ prolapse, the prolapsed organs may spontaneously retract with bed rest in mild cases, while they may remain irreducible in severe cases. Long-term exposure of the prolapsed cervix and vaginal mucosa to friction from clothing can lead to ulceration and bleeding. Secondary infections can result in purulent discharge.

Uterine prolapse, regardless of severity, typically does not interfere with menstruation. Mild uterine prolapse does not usually affect conception, pregnancy, or delivery.

Signs

The anterior and posterior vaginal walls, the cervix, or the uterine body may protrude through the vaginal introitus. The mucosa covering the prolapsed structures often becomes thickened and keratinized, with potential ulceration or bleeding.

With posterior vaginal wall prolapse, rectal examination may reveal the rectum bulging into the vaginal lumen, forming a blind-sac-like structure. An enterocele presents as a spherical protrusion in the posterior fornix, with loops of bowel palpable within the hernia sac during rectal examination.

Uterine prolapse in younger patients is often accompanied by cervical elongation and hypertrophy. As the prolapsed uterus descends, the bladder and ureters are displaced downward, aligning with the urethral orifice to form a triangular configuration.

Figure 6 Diagram illustrating ureter displacement

Clinical Staging

There are various methods for clinical staging, with the pelvic organ prolapse quantification (POP-Q) system being the most widely used internationally. Clinical practice does not strictly mandate a single method of staging. Consistent use of the same method before and after surgical treatment is sufficient. Prolapse severity is assessed based on the maximum degree of descent during the Valsalva maneuver. Uterine prolapse is categorized into three degrees:

- First-degree (mild): The external cervical os is less than 4 cm from the hymenal ring and has not reached it.

- First-degree (severe): The cervix has reached the hymenal ring and is visible at the vaginal introitus.

- Second-degree (moderate): The cervix has descended beyond the vaginal introitus, but the uterine body remains within the vaginal canal.

- Second-degree (severe): A portion of the uterine body has prolapsed beyond the vaginal introitus.

- Third-degree (severe): Both the cervix and the uterine body have fully prolapsed outside the vaginal introitus.

Anterior vaginal wall prolapse is also divided into three degrees:

- First-degree: The anterior vaginal wall forms a bulge that reaches the hymenal ring but remains within the vaginal canal.

- Second-degree: The vaginal wall flattens or disappears, and part of the anterior vaginal wall protrudes beyond the vaginal introitus.

- Third-degree: The entire anterior vaginal wall has prolapsed beyond the vaginal introitus.

Posterior vaginal wall prolapse is categorized similarly:

- First-degree: The posterior vaginal wall has descended to the hymenal ring but remains within the vaginal canal.

- Second-degree: A portion of the posterior vaginal wall has prolapsed beyond the vaginal introitus.

- Third-degree: The entire posterior vaginal wall has prolapsed beyond the vaginal introitus.

Figure 7 Diagram illustrating uterine prolapse staging

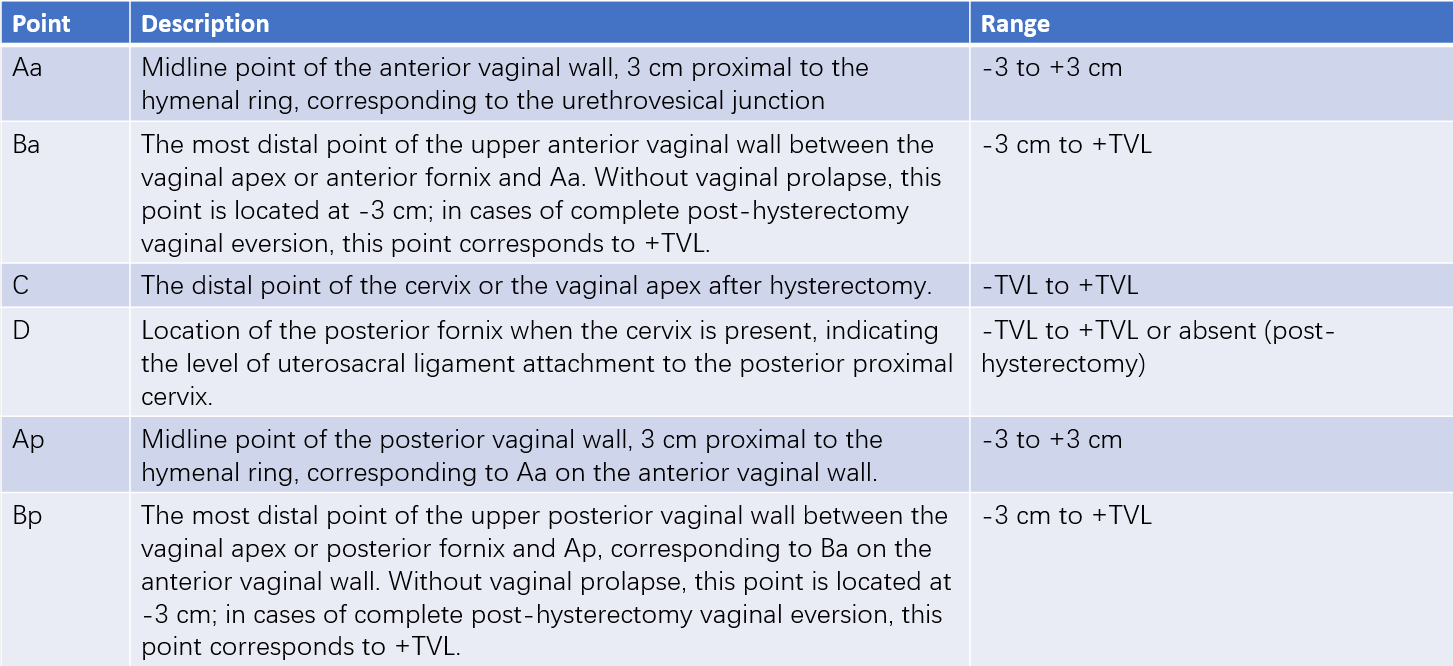

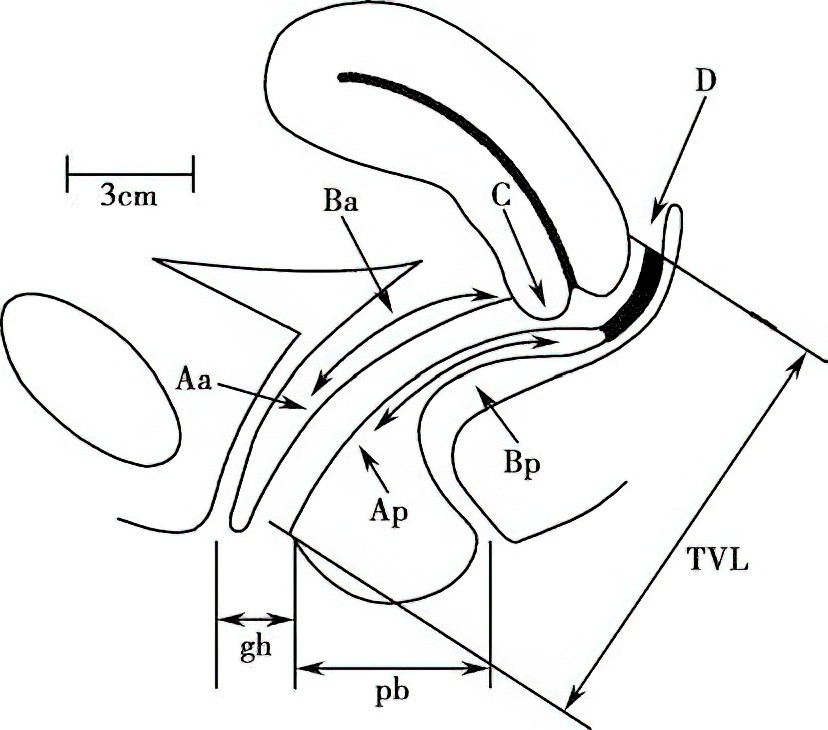

The POP-Q system proposed by Bump is commonly used internationally for the quantification of pelvic organ prolapse. This system evaluates prolapse by referencing six anatomical points on the anterior vaginal wall, vaginal apex, and posterior vaginal wall relative to the hymenal ring. The hymenal plane is designated as 0, with points above the hymen assigned negative values and points below assigned positive values.

- The anterior vaginal wall is measured at points Aa and Ba,

- The vaginal apex is measured at points C and D,

- The posterior vaginal wall is measured at points Ap and Bp, which correspond to Aa and Ba on the anterior vaginal wall.

Additional parameters include:

- Genital hiatus (gh): The midline distance from the external urethral meatus to the posterior margin of the hymenal ring.

- Perineal body (pb): The distance from the posterior margin of the genital hiatus to the midpoint of the anus.

- Total vaginal length (TVL): The total length of the vaginal canal.

All measurements are recorded in centimeters.

Table 1 Pelvic organ prolapse assessment points (POP-Q technique)

Note: POP-Q staging involves measuring the farthest extent of prolapse during maximal Valsalva maneuver. Results are recorded using positive or negative values relative to the hymenal plane.

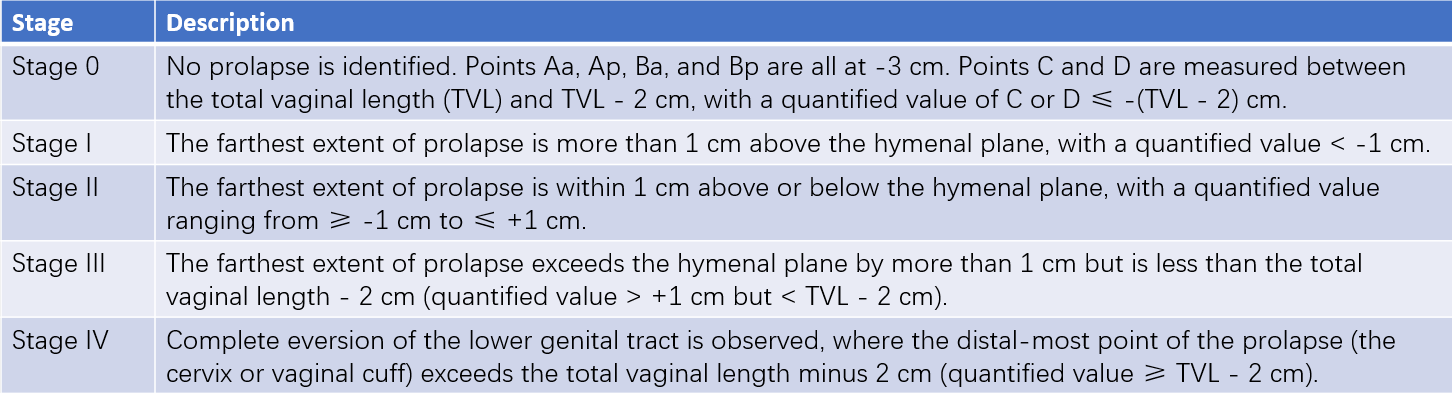

Table 2 Pelvic organ prolapse quantification (POP-Q staging)

Note: POP-Q staging is based on the farthest extent of prolapse during maximal Valsalva maneuver. Prolapse should be assessed and quantified for each point in a 3×3 grid, followed by classification into the respective stage. To account for vaginal elasticity and inherent measurement error, a 2 cm margin is permitted in TVL values for stages 0 and IV.

The POP-Q system records these measurements in a 3×3 grid, providing an objective representation of prolapse at various anatomical sites.

Figure 8 Illustration of pelvic organ prolapse quantification (POP-Q)

In addition to anatomical staging, assessing symptom severity and functional impairments caused by pelvic organ prolapse is vital. Pre- and post-operative evaluations should include inquiries into urinary, bowel, and sexual symptoms. The Pelvic Floor Impact Questionnaire Short Form 7 (PFIQ-7) and the Pelvic Organ Prolapse/Urinary Incontinence Sexual Questionnaire (PISQ) are recommended for evaluating symptom severity and the impact on quality of life. These tools allow for more accurate assessment of pelvic floor function and surgical outcomes.

Diagnosis

A diagnosis is straightforward based on the patient’s history and physical examination findings. Before a gynecological examination, patients should be instructed to perform a Valsalva maneuver to determine the maximum degree of prolapse and appropriate staging. The presence, location, size, and depth of any ulcers, as well as signs of infection, should also be noted.

Patients should be observed for stress urinary incontinence by asking them to cough while their bladder is full. Cervical length should be assessed, and cervical cytology performed. In cases of severe uterine prolapse, uterine size should be palpated, and the prolapsed uterus should be manually reduced to perform a bimanual exam for adnexal masses. A single-blade speculum may assist in a thorough vaginal examination. Compression of the anterior vaginal wall during the Valsalva maneuver may reveal an enterocele or rectocele.

Pelvic floor muscle examination should include assessments of levator ani muscle strength and genital hiatus width. In cases of bowel incontinence, rectal examination should evaluate the function of the anal sphincter.

Differential Diagnosis

Vaginal Wall Masses

Vaginal wall masses are fixed and confined within the vaginal wall, with well-defined borders. In cystocele, a hemispherical protrusion is observed on the anterior vaginal wall, which is soft. Rectal examination may reveal the cervix and uterine body overlying the mass.

Cervical Elongation

Bimanual examination reveals an elongated cervix within the vaginal canal, with the uterine body remaining in the pelvic cavity and no descent during the Valsalva maneuver.

Submucosal Uterine Fibroids

Patients often have a history of menorrhagia. A red, firm mass protrudes from the external cervical os, with no visible cervical os in its center. However, the thin and distended edges of the cervix can usually be palpated around the mass.

Treatment

Non-Surgical Therapy

Non-surgical treatment is typically applied to symptomatic patients with POP-Q stage I to II prolapse. It is also suitable for patients seeking to preserve fertility, those unable to tolerate or unwilling to undergo surgery, and those with severe prolapse (POP-Q stage III to IV) or mild to moderate prolapse as defined by conventional staging systems. The goal of non-surgical therapy is to alleviate symptoms, enhance the strength, endurance, and support of the pelvic floor muscles, prevent the progression of prolapse, and avoid or delay the need for surgical intervention. Current non-surgical treatment options include the use of pessaries, pelvic floor rehabilitation, and behavioral guidance.

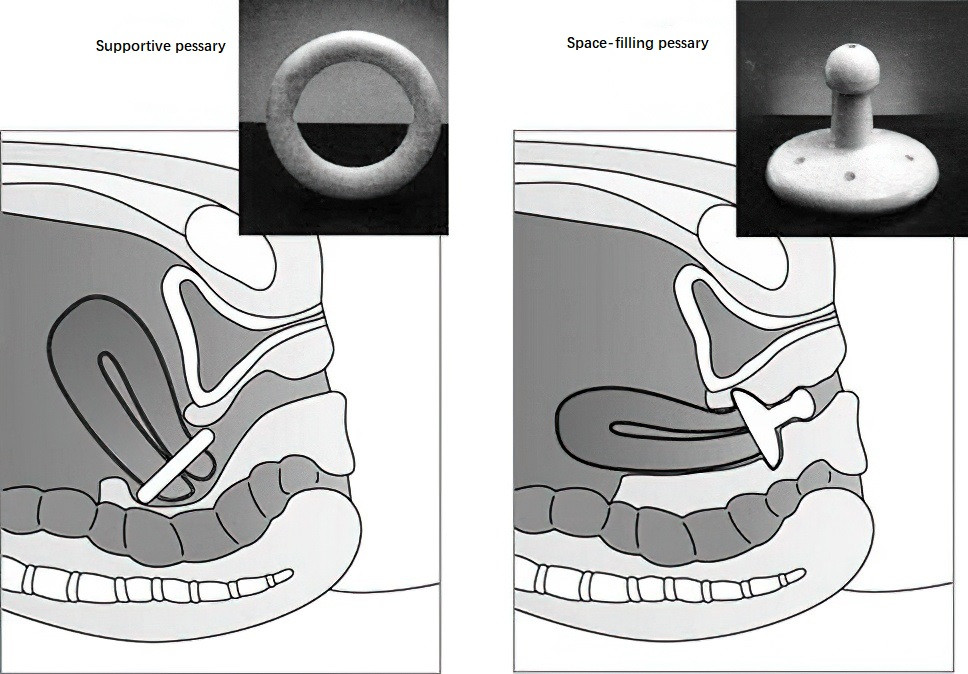

Pessaries are support devices designed to maintain the uterus and vaginal walls within the vaginal canal. They are classified into supportive and space-filling types and serve as the first-line therapy for pelvic organ prolapse. Pessaries are particularly useful for situations such as poor overall health precluding surgery, pregnancy or postpartum, or ulceration of the prolapsed tissue, where they promote healing prior to surgery.

Figure 9 Diagram illustrating various types of pessaries

However, pessary use may result in vaginal irritation and ulceration. Intermittent removal, cleaning, and reinsertion of the device are necessary to prevent severe complications such as fistula formation, impaction, and infections.

Pelvic floor rehabilitation aims to improve the tone of the pelvic floor muscles. Pelvic muscle (levator ani) exercises are effective for patients with mild prolapse (domestic grading) or POP-Q stage I or II prolapse. These exercises can also serve as adjunctive therapy before and after surgery in severe cases. Kegel first proposed self-guided exercises, where patients contract their anal muscles and hold the contraction for at least 3 seconds before relaxing. These exercises are repeated for 10–15 minutes, 2–3 times daily. Pelvic muscle training with biofeedback has shown even greater efficacy.

Surgical Therapy

Surgical intervention may be considered for symptomatic patients with prolapse extending beyond the hymenal ring. Treatment plans should be individualized based on the patient's age, reproductive desires, and overall health status. The primary objectives of surgery are to alleviate symptoms, restore normal anatomy and organ function, maintain satisfactory sexual function, and achieve durable outcomes. Common surgical procedures include those targeting anatomical correction and combined approaches for coexisting stress urinary incontinence, such as bladder neck suspension or mid-urethral sling procedures. Surgery can be categorized into vaginal closure procedures and reconstructive procedures.

Vaginal Closure Surgery

This includes partial vaginal closure (LeFort procedure) and total vaginal closure. During these procedures, rectangular areas of mucosa are excised from the anterior and posterior vaginal walls, and the resulting raw surfaces are sutured together to partially or completely close the vaginal canal. These surgeries result in the loss of sexual function and are thus reserved for elderly, frail patients unable to tolerate more extensive procedures.

Pelvic Floor Reconstructive Surgery

Reconstructive procedures focus on repairing the middle pelvic compartment. Vaginal vault tissue or uterosacral ligaments may be suspended and anchored to the sacrospinous ligament, sacral promontory, or anterior longitudinal ligament of the sacrum using sutures, mesh, or slings. Uterine preservation or removal may be considered depending on individual cases. These surgeries can be performed vaginally, laparoscopically, or via open abdominal approaches. Common procedures include sacrocolpopexy, sacrospinous ligament suspension, and uterosacral ligament suspension.

Autologous Tissue Repair and Reconstruction

This involves:

- Sacrospinous ligament fixation: Reconstructs level I support by suspending the vaginal apex to the sacrospinous ligament.

- Uterosacral ligament suspension: Achieves level I support by shortening and suturing the uterosacral ligaments for apex suspension.

- Anterior and posterior vaginal wall repair: Focuses on fascial repair to address level II defects.

Manchester Operation

This procedure is suitable for younger patients with uterine prolapse due to cervical elongation and involves anterior and posterior vaginal wall repair, uterosacral ligament shortening, and partial cervical amputation.

Abdominal or Laparoscopic Uterine/Vaginal Sacrocolpopexy

This reconstructs level I support by suspending the apex to the anterior longitudinal ligament of the sacrum.

Vaginal Mesh Surgery

This involves the use of a mesh implant to achieve level I apex support by anchoring the tape to the sacrospinous ligament and level II fascial reinforcement via insertion into the anterior and posterior vaginal walls. Although this approach achieves favorable clinical outcomes, severe complications related to mesh use have been reported. The United States FDA has banned the use of vaginal mesh due to safety concerns, and its application remains controversial within the field.

Postoperative Management and Follow-Up

Measures to prevent intra-abdominal pressure increases and heavy lifting should be taken for three months following surgery. Sexual activity should be avoided for three months or until the vaginal mucosa has healed completely. Regular lifelong follow-up is recommended to identify recurrences and address surgical complications promptly.

Prevention

Conditions and labor activities that increase intra-abdominal pressure should be avoided. For patients undergoing hysterectomy with concurrent uterine prolapse, apical reconstruction should be performed simultaneously to prevent postoperative vault prolapse or enterocele formation.