Abnormal Development of the External Genitalia

The most common type of external genitalia malformation is imperforate hymen, also known as the absence of a hymenal opening. This occurs during development when the distal portion of the urogenital sinus fails to canalize. Due to the absence of an opening in the hymen, vaginal secretions or menstrual blood during menarche are obstructed and accumulate in the vagina. In some cases, menstrual blood may flow retrograde through the fallopian tubes into the abdominal cavity. Without timely incision and drainage, repeated menstrual bleeding leads to progressive accumulation of blood, causing hematocolpos, hematometra, hematosalpinx, and even pelvic hematoma. Adhesions of the fallopian tubes may result in fimbrial blockages, while retrograde menstrual flow into the pelvic cavity increases the risk of endometriosis. Certain anomalies of hymenal development may also present as cribiform hymen or septate hymen.

The majority of patients exhibit symptoms at puberty, including cyclical lower abdominal pain that progressively worsens, without menstrual bleeding. Severe cases may result in symptoms such as rectal pain, urinary frequency, and difficulties in urination or defecation. Physical examination may reveal a bulging hymen with a bluish-purple surface. Digital rectal examination may detect a cystic mass in the pelvis. Rarely, prepubertal girls may present with an outwardly protruded hymen due to retained mucosal secretions in the vagina. Gynecological ultrasound imaging may show fluid or blood retention in the vaginal cavity. Upon diagnosis, treatment typically involves surgical intervention, most often an X-shaped incision.

Abnormal Development of the Vagina

Vaginal developmental anomalies result from defects during the formation or fusion of the Müllerian ducts (paramesonephric ducts). According to the 1998 classification by the American Society for Reproductive Medicine, vaginal anomalies are categorized as follows:

Müllerian Agenesis or Hypoplasia

This includes cases where the uterus and vagina fail to develop, also known as Mayer-Rokitansky-Küster-Hauser syndrome (MRKH syndrome), or congenital absence of the uterus and vagina.

Urogenital Sinus Dysgenesis

Atypical presentations include partial vaginal atresia.

Müllerian Fusion Abnormalities

These are further divided into vertical fusion defects, such as transverse vaginal septum, and lateral fusion defects, such as longitudinal vaginal septum or oblique vaginal septum syndrome.

Mayer-Rokitansky-Küster-Hauser (MRKH) Syndrome

MRKH syndrome results from bilateral agenesis or hypoplasia of the Müllerian ducts or their caudal ends. The incidence is approximately 1 in 4,000–5,000 females. The condition manifests as congenital absence of the vagina, commonly associated with the absence of the uterus or the presence of only rudimentary uterine structures. Ovarian function is typically normal. Patients present with primary amenorrhea and difficulties in sexual activity.

Physical examination reveals normal physical development, secondary sexual characteristics, and external genitalia, but absence of a vaginal orifice. In some cases, a shallow pit in the posterior vestibule or a short vaginal blind end may be observed. Based on the presence or absence of additional anomalies in the urinary, skeletal, or other systems, MRKH syndrome is classified into Type I (isolated) and Type II (complex) subtypes. The karyotype is 46,XX, and sex hormone levels are consistent with normal female values.

Treatment is typically recommended after the age of 18. Non-surgical methods are the first-line treatment, with the most common method being pressure dilation therapy. This involves the use of a vaginal dilator to press and expand the vaginal dimple to restore a functional vaginal length. In cases where pressure dilation fails or the patient cannot tolerate it, surgical options for vaginoplasty may be considered. Surgical methods create a neovaginal space between the bladder and rectum and may incorporate materials such as biological grafts, peritoneum, or sigmoid colon segments to form the new vaginal lining.

Vaginal Atresia

Vaginal atresia results from distal Müllerian duct anomalies. Based on anatomical characteristics, vaginal atresia is categorized as follows:

Lower Vaginal Atresia

Also known as Type I vaginal atresia, this condition involves developmental anomalies limited to the lower third of the vagina, with normal upper vaginal segments, cervix, and uterus.

Complete Vaginal Atresia

Also known as Type II vaginal atresia, this condition often coexists with cervical hypoplasia, while the uterine body may be normal or exhibit functional endometrial tissue despite deformities.

In cases of lower vaginal atresia, symptoms appear earlier due to normal endometrial function. Symptoms include upper vaginal dilation and, in severe cases, hematometra, hematocolpos, and even retrograde menstrual flow into the pelvis, potentially causing endometriosis. Gynecological examination may reveal a cystic mass with hematocolpos anterior to the rectum and absence of a vaginal opening in the vestibule. The surface of the atretic mucosa appears normal and does not bulge outward. Digital rectal examination detects a mass projecting toward the rectum, located higher than in cases of imperforate hymen.

Patients with complete vaginal atresia often have coexisting uterine hypoplasia and abnormal endometrial function. Symptoms appear later, and hematocolpos is uncommon, though retrograde menstrual flow into the pelvis frequently leads to endometriosis. Ultrasonography and MRI are valuable tools for diagnosis.

Upon confirmation of the diagnosis, early surgical intervention is recommended to relieve obstruction, reconstruct the vaginal canal, and prevent re-adhesion. Surgical design depends on the length of the atretic segment. If the atretic segment is less than 3 cm, direct pull-through vaginoplasty with temporary use of a vaginal dilator is an option to maintain patency. For atretic segments ≥3 cm, the use of peritoneum, amniotic tissue, or biological grafts for lining the new vaginal canal is recommended, with prolonged dilator placement and regular dilation postoperatively to prevent stricture. Staged surgical approaches may involve initial catheter drainage of menstrual blood, followed by vaginoplasty with dilator placement.

In cases of complete vaginal atresia, thorough evaluation of cervical hypoplasia is necessary. Surgical options include hysterectomy, uterovaginal anastomosis, or cervical canalization procedures.

Transverse Vaginal Septum

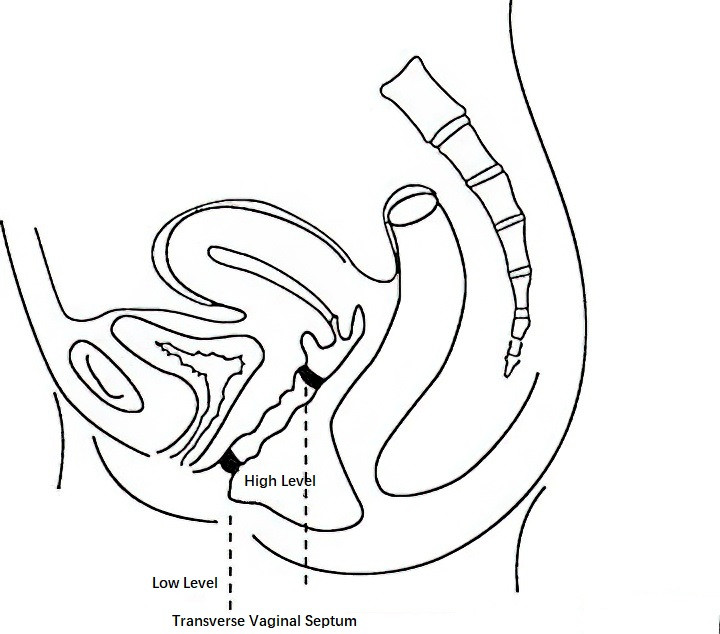

Transverse vaginal septum results from incomplete or partial failure of canalization at the connection between the caudal end of the Müllerian ducts and the urogenital sinus following their fusion. It is rarely associated with anomalies in the urinary system or other organs. The majority of septa are located in the upper or middle third of the vagina. A transverse septum without an opening is classified as a complete septum, while a septum with a small opening is referred to as an incomplete septum.

Figure 1 Diagram of transverse vaginal septum

Incomplete transverse septa located in the upper vagina are often asymptomatic, whereas lower-positioned septa may impair sexual intercourse and, during vaginal delivery, hinder fetal descent. Complete transverse septum may cause primary amenorrhea accompanied by cyclical abdominal pain that progressively worsens. Incomplete septum may be identified during gynecological examination through shortened vaginal length or a blind pouch. A small central opening may be seen in the septum, and digital rectal examination can palpate both the uterine cervix and body. In cases of complete septum, retained menstrual blood may form a mass palpable above the level of the septum.

Surgical treatment involves excision of the septum with hemostatic suturing. Alternatively, a serrated incision followed by staggered suturing may reduce the risk of postoperative stricture formation, and the placement of a vaginal mold can help prevent such complications.

During childbirth, if the septum is thin, it may be incised when the fetal presenting part compresses the septum; the septum is then excised after delivery of the fetus. In cases of thicker septa, cesarean section is preferred. Postoperatively, regular vaginal dilation or mold placement is required to prevent stricture formation.

Longitudinal Vaginal Septum

Longitudinal vaginal septum occurs due to incomplete or partial regression of the vertical partition at the caudal end of the Müllerian ducts following their fusion. It is often accompanied by uterine anomalies such as double uterus or double cervix. Longitudinal septa may be classified as complete or incomplete; the former extends to the vaginal introitus, while the latter does not.

Complete longitudinal septa are frequently asymptomatic but may lead to dyspareunia due to narrowed vaginal space. Incomplete septa can cause discomfort or difficulties during sexual activity and may obstruct fetal descent during labor. Vaginal examination reveals the presence of a mucosal wall dividing the vagina into two longitudinal channels, with the upper end of the partition near the cervix. For women whose sexual function is affected by the septum, surgical removal of the longitudinal septum is recommended.

If a longitudinal vaginal septum is discovered during vaginal delivery, it may be bisected in the middle when the fetal presenting part compresses it, and the septum is completely excised after the fetus is delivered.

Oblique Vaginal Septum Syndrome (OVSS)

The exact cause of oblique vaginal septum syndrome is unclear, but it may result from failure of one Müllerian duct to extend downward to meet the urogenital sinus, forming a blind end. It is commonly associated with ipsilateral urinary system anomalies, such as absence of the kidney on the same side as the septum, along with anomalies such as double uteri and double cervices.

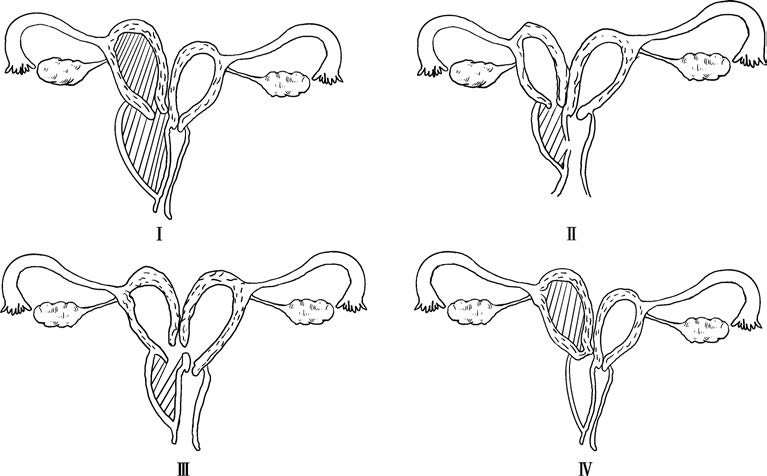

Figure 2 Diagram of the four types of oblique vaginal septum syndrome

According to expert consensus on the nomenclature and definition of female reproductive tract anomalies, OVSS is classified into four types:

- Type I: Imperforate oblique septum. The uterus on the side of the septum is completely isolated from the external environment and the contralateral uterus, leading to hematometra within the cavity behind the septum.

- Type II: Perforate oblique septum. A small opening is present on the septum, allowing limited drainage of menstrual blood from the isolated uterine cavity; however, drainage remains inadequate.

- Type III: Imperforate oblique septum with cervical fistula. A small fistula connects the cervical regions of both uteri or the vaginal cavity behind the septum to the cervix of the contralateral uterus. Menstrual blood from the isolated side may drain through the fistula; however, drainage remains insufficient.

- Type IV: Cervical atresia type. The cervix on the atretic side is underdeveloped, and the vaginal cavity behind the oblique septum is narrow with no hematometra; in some cases, this vaginal cavity may even be absent.

All four types are associated with dysmenorrhea, with Type I and Type IV causing more severe pain. Persistent unilateral lower abdominal pain is often observed. Types II and III are associated with prolonged menstrual periods and occasional intermenstrual spotting. Infections may lead to purulent discharge. Regular menstrual cycles are observed across all four types.

Gynecological examination may identify a cystic mass in one vaginal fornix or vaginal wall. Types I and IV are marked by firm masses and may be accompanied by uterine enlargement or adnexal masses. Types II and III typically present with masses of lower tension, and compression of the mass may result in the discharge of old blood. Diagnosis is confirmed by aspirating retained blood from the mass after local disinfection and puncture of the lower portion of the mass. Ultrasonography may detect hematometra in one uterine cavity, a vaginal cyst, and ipsilateral renal agenesis. Evaluation of the urinary system with imaging is recommended when necessary.

Oblique vaginal septum can be treated with a vaginal or hysteroscopic septum resection procedure. The key to surgery is complete removal of the septum and ensuring unobstructed drainage. Postoperatively, measures should be taken to prevent adhesions at the surgical site. For patients with Type IV, removal of the obstructed uterus and fallopian tube is recommended after confirmation of the diagnosis.

Cervical and Uterine Developmental Abnormalities

These conditions primarily arise from abnormalities in the development or fusion of the Müllerian ducts at the uterine segment.

Congenital Cervical Dysplasia

Congenital cervical dysplasia encompasses a range of anomalies including agenesis of the cervix, cord-like cervix, cervical atresia, cervical remnants, congenital cervical canal stenosis, cervical angulation abnormalities, congenital cervical elongation with cervical canal stenosis, and duplication of the cervix. These anomalies are clinically rare. If endometrial function is present, blood accumulation within the uterine cavity may cause cyclical abdominal pain after the onset of puberty. Retrograde menstrual flow through the fallopian tubes into the peritoneal cavity may result in pelvic endometriosis. Ultrasound and magnetic resonance imaging (MRI) are useful for diagnosis. Uterine-cervical continuity may be established through surgical interventions to create an artificial uterovaginal canal, but complications such as postoperative cervical adhesions and stenosis are common, and additional surgeries may be required.

Uterine Hypoplasia

Uterine hypoplasia consists of:

Primordial Uterus

This form occurs when development halts shortly after the fusion of the Müllerian ducts. The uterus remains extremely small, often with either no uterine cavity or a solid muscular uterus without endometrial tissue.

Infantile Uterus (Hypoplastic Uterus)

This condition occurs when development ceases after the fusion of the Müllerian ducts and the formation of the uterus. The uterine cavity is present and contains endometrial tissue.

In both cases, ovarian function is normal. Primordial uterus is asymptomatic and is often diagnosed upon evaluation for amenorrhea after puberty. No specific treatment is usually required. For infantile uterus, if menstrual blood retention or retrograde flow causes cyclical abdominal pain, surgical intervention to remove the affected uterus may be necessary.

Unicornuate Uterus and Rudimentary Uterine Horn

Unicornuate Uterus

This form results when only one Müllerian duct develops normally, forming a single uterine cavity. The ovary on the same side is typically functional, whereas the opposite Müllerian duct fails to develop or canalize, leading to the absence of the ovary, fallopian tube, and often the kidney on the undeveloped side.

Rudimentary Uterine Horn

This anomaly occurs when one side of the Müllerian duct partially develops, resulting in a rudimentary uterine horn. A normal ovary and fallopian tube may be present on this side, but this condition is often accompanied by abnormalities of the ipsilateral urinary system. The rudimentary uterine horn can be classified into:

- A horn with a uterine cavity that communicates with the unicornuate uterus;

- A horn with a uterine cavity that does not communicate with the unicornuate uterus;

- A non-cavitary horn that is a solid fibrous structure connected to the unicornuate uterus by a fibrous band.

Unicornuate uterus is typically asymptomatic. Rudimentary horns containing functional endometrial tissue but lacking communication with the unicornuate uterus may cause dysmenorrhea, hematometra, or retrograde bleeding, potentially leading to endometriosis. Imaging techniques such as hysterosalpingography, ultrasound, and MRI assist in diagnosis. Unicornuate uteri are not typically treated. Rudimentary horns without functional endometrium do not require treatment, whereas functional rudimentary horns should be surgically removed along with the ipsilateral fallopian tube after diagnosis.

Pregnancies located in a rudimentary horn discovered during early or mid-gestation require surgical excision of the horn to prevent uterine rupture. If diagnosed during late gestation, excision is performed after cesarean delivery.

Uterus Didelphys

Uterus didelphys occurs when the two Müllerian ducts fail to fuse, resulting in the development of two separate uteri and two cervices. In some cases, one cervix may be underdeveloped or absent. This condition may also coexist with longitudinal or oblique vaginal septa. Examination may reveal a bifurcated uterus. Hysteroscopy or hysterosalpingography may reveal the presence of two uterine cavities. Typically, no treatment is necessary.

Bicornuate Uterus and Arcuate Uterus

Bicornuate Uterus

This condition arises when partial fusion of the two Müllerian ducts results in two independent uterine horns connected by a common uterine cavity. Typically, there is one cervix, and the uterine fundus exhibits a serosal indentation greater than 1 cm. Based on whether the septal tissue extends to the internal os, bicornuate uteri are classified as complete or partial. This condition is often asymptomatic, though some cases may involve heavy menstrual bleeding and dysmenorrhea. Examination may detect a depression in the uterine fundus. Ultrasound, MRI, or hysterosalpingography supports diagnosis. Generally, treatment is not required.

Arcuate Uterus

This condition is characterized by a mild concavity of the uterine fundus, with an intramyometrial indentation less than 1 cm. It does not meet the criteria for diagnosing a septate uterus. Arcuate uterus is usually asymptomatic and is not associated with adverse pregnancy outcomes, so treatment is unnecessary.

Septate Uterus

Septate uterus is the most common form of uterine anomaly. It is divided into two types:

Complete Septate Uterus

In this type, the septum extends to or beyond the internal os, resembling the appearance of a uterus with two cervices.

Incomplete Septate Uterus

Here, the septum ends above the level of the internal os.

Symptoms are typically absent. However, in women of reproductive age, this condition may affect pregnancy outcomes, including recurrent miscarriage, preterm birth, and premature rupture of membranes, with recurrent pregnancy loss being the most common complication. Transvaginal ultrasound is currently the most frequently used diagnostic method, with 3D ultrasound considered more accurate for measurement. Imaging typically shows two endometrial echo patterns without significant indentation at the uterine fundus. The length of the intrauterine septum exceeds 1 cm when measured from a line connecting the tubal ostia, and the angle of the septum is ≤90°.

Current evidence does not support routine prophylactic removal of a septate uterus. However, for women with a history of recurrent pregnancy loss or infertility, surgical treatment via hysteroscopic septum resection is the preferred option. Pregnancy is typically viable two months after surgery.

Developmental Abnormalities of the Fallopian Tubes

Developmental abnormalities of the fallopian tubes are rare and arise from incomplete development of the cranial ends of the Müllerian ducts. Isolated agenesis of the fallopian tubes is almost non-existent and is typically accompanied by abnormalities in the uterus and cervix. These anomalies are often detected incidentally during surgeries performed for other conditions. Common types include:

- Agenesis or Rudimentary Fallopian Tube: Complete absence or presence of a remnant of the fallopian tube.

- Hypoplasia of the Fallopian Tube: Underdevelopment of one or both fallopian tubes.

- Accessory Fallopian Tube: An additional, often anomalous fallopian tube structure.

- Unilateral or Bilateral Double Fallopian Tubes: Duplication of one or both fallopian tubes.

Developmental Abnormalities of the Ovaries

Developmental abnormalities of the ovaries include:

- Ovarian Agenesis or Dysplasia: Cases of ovarian dysplasia are also referred to as streak ovaries, which are typically observed in individuals with gonadal dysgenesis.

- Ectopic Ovary or Failure of Ovarian Descent: Ovaries remain in various positions along the descent pathway of the primordial gonadal ridge, failing to reach the pelvic cavity. This condition is closely associated with the connection between the ovary and ligament structures attached to the Müllerian ducts.

- Supernumerary Ovary: Presence of an additional ovary, separate from the usual pair.