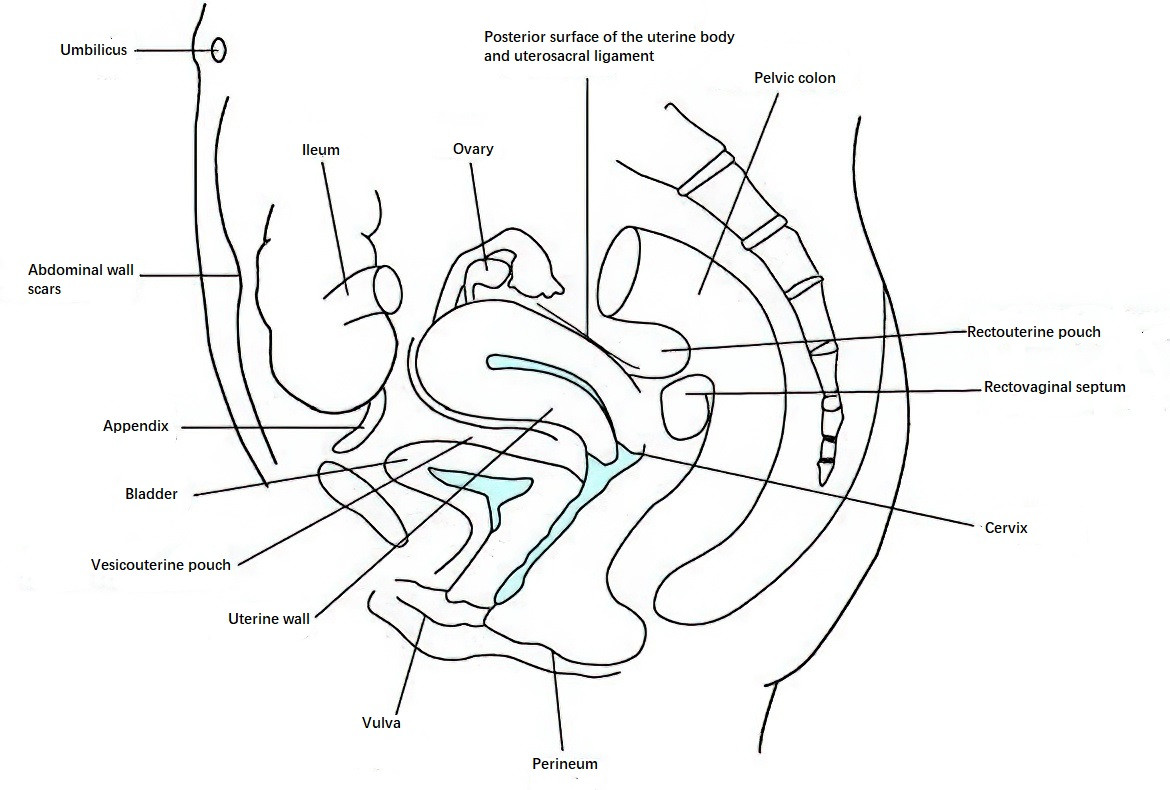

Endometriosis (EMT) is a condition characterized by the presence of endometrial tissue (glands and stroma) outside the uterine cavity. It is commonly referred to as ectopic endometriosis. The ectopic endometrial tissue can invade any part of the body, with the ovaries and uterosacral ligaments being the most common sites. Other frequent locations include the uterus, other visceral and parietal peritoneum, and the rectovaginal septum. Less commonly, endometriotic lesions can be found in locations such as the umbilicus, bladder, kidneys, ureters, lungs, pleura, breasts, and even the arms and thighs. However, the majority of cases occur in the pelvic organs and peritoneum, leading to the description of "pelvic endometriosis." Although the lesions appear benign morphologically, endometriosis is clinically aggressive, prone to recurrence, and displays invasive behavior. Endometriosis is a hormone-dependent disease; during natural or induced menopause (via medication, irradiation, or surgical bilateral oophorectomy), the ectopic lesions often undergo gradual atrophy and absorption. Pregnancy or ovarian suppression therapy using sex hormones can temporarily halt disease progression.

Figure 1 Locations of endometriosis lesions

Prevalence

Epidemiological surveys indicate that endometriosis is a common and prevalent disease among women of reproductive age, affecting approximately 10% of this population. Among these cases, 76%–85% occur in individuals aged 25–45 years, consistent with the hormone-dependent nature of the disease. Endometriosis is associated with infertility in 20%–50% of affected individuals and with chronic pelvic pain in 71%–87% of cases. There are also reports of endometriosis in postmenopausal individuals undergoing hormone replacement therapy. The incidence is higher in those with fewer pregnancies or delayed childbirth compared to individuals with multiple or earlier pregnancies. In recent years, the incidence of endometriosis has increased significantly. This trend has been correlated with higher socioeconomic status, rising cesarean section rates, and increased occurrences of abortions and hysteroscopic procedures.

Contributing Factors

The specific origins of ectopic endometrial tissue remain unclear. Several hypotheses have been proposed to explain the etiology of endometriosis.

Implantation Theory

In 1927, Sampson proposed the implantation theory, which posits that ectopic endometrial tissue originates from the uterine endometrial lining. Endometrial cells are believed to migrate outside the uterus, implant in other locations, grow, and form lesions. The proposed mechanisms of dissemination include the following:

- Retrograde Menstruation: During menstruation, endometrial glandular epithelial cells and stromal cells may travel backward with menstrual blood through the fallopian tubes into the pelvic cavity, where they implant on the ovaries and adjacent peritoneal surfaces. These lesions then grow and spread, leading to pelvic endometriosis. This is known as the retrograde menstruation hypothesis.

- Lymphatic and Venous Spread: Endometrial cells may metastasize through the lymphatic or venous systems, leading to ectopic implantation in distant organs. Endometriosis in remote sites, such as the lungs or the skin and muscles of the extremities, may result from hematogenous or lymphatic dissemination.

- Iatrogenic Implantation: Endometriosis may occur at surgical sites, such as abdominal incisions following cesarean sections or episiotomy sites, due to the transfer and direct implantation of endometrial cells during surgery.

Coelomic Metaplasia Theory

This theory, proposed by the eminent 19th-century pathologist Robert Meyer, suggests that the surface epithelium of the ovaries and the peritoneum of the pelvis, which are derived from embryonic coelomic epithelial cells with high metaplastic potential, can be transformed into endometrial-like tissue. This process may be triggered by repeated stimulation from ovarian hormones, menstrual blood, or chronic inflammation.

Induction Theory

According to this theory, undifferentiated peritoneal tissue can develop into endometrial tissue under the influence of endogenous biochemical factors. Ectopic endometrial tissue is thought to secrete chemical substances that induce undifferentiated mesenchymal tissue to form additional ectopic lesions.

Genetic Factors

Endometriosis has been associated with genetic susceptibility and familial clustering. First-degree relatives of individuals with endometriosis have a sevenfold increased risk of developing the condition compared with those without a family history. Studies of monozygotic twins indicate that when one twin has endometriosis, the probability of the other twin being affected reaches approximately 75%. Additionally, genetic polymorphisms in genes such as glutathione S-transferase, galactosyltransferase, and estrogen receptor genes have been implicated in the development of endometriosis.

Immune and Inflammatory Factors

Disorders in immune regulation play a crucial role in the development and progression of endometriosis. Reduced immune surveillance and weakened cytotoxic activity of immune cells impair the clearance of ectopic endometrial cells. In individuals with endometriosis, elevated levels of macrophages, pro-inflammatory cytokines, growth factors, and pro-angiogenic substances have been detected in peritoneal fluid. Prostaglandin E2 (PGE2) contributes to abnormal aromatase expression, promoting localized inflammation and the progression of lesions.

Other Factors

In-Situ Endometrium Determinants Theory suggests that the biological properties of eutopic endometrial tissue, such as its increased adhesion, invasiveness, and angiogenic potential, are key determinants in the development of endometriosis. Local microenvironmental factors may further influence this process. Environmental toxins, such as polychlorinated biphenyls (PCBs) and dioxins, have also been implicated in the potential pathogenesis of endometriosis.

Pathology

The primary pathological change in endometriosis involves ectopic endometrial tissue undergoing cyclic bleeding in response to ovarian hormone fluctuations. Repeated local bleeding and the slow absorption of lesions lead to fibrosis, cyst formation, and adhesions in the surrounding tissues. Lesions often appear as purplish-brown spots or vesicles and eventually develop into nodules or masses of varying sizes with a purplish-brown appearance. Endometriosis can be classified into different pathological types based on its location.

Gross Examination

Ovarian Endometriosis

The ovaries are the most common site of ectopic endometrial invasion. Unilateral involvement occurs in 80% of cases, while bilateral involvement is observed in 50%. Ovarian endometriosis lesions can be classified into two types:

- Microscopic Lesions: These are superficial lesions on the ovarian surface, appearing as red, blue, or brown spots or small cysts, which are only a few millimeters in size. Microscopic lesions often cause adhesions between the ovaries and surrounding tissues. When punctured during surgery, thick, coffee-colored fluid may drain from the cysts.

- Typical Lesions (Cystic Type): Also known as cystic ovarian endometriosis, these lesions involve the growth of ectopic endometrial tissue within the ovarian cortex, forming single or multiple cysts. These cysts typically have a gray-blue surface and vary in size, with an average diameter around 5 cm but can reach 10–20 cm. Old blood accumulates inside these cysts, forming thick, coffee-colored fluid reminiscent of chocolate, leading to their nickname "chocolate cysts of the ovary." The cyclic bleeding within the cysts increases internal pressure, making the cyst walls prone to rupture. Ruptured cyst contents irritate the peritoneum, triggering localized inflammatory responses and fibrosis, resulting in firm adhesions between the ovary and adjacent organs or tissues. These adhesions restrict cyst mobility. Large cyst rupture, either spontaneously or due to external force, can cause significant spillage into the pelvic and abdominal cavities, inducing peritoneal irritation and acute abdominal symptoms.

Peritoneal Endometriosis

This type involves lesions on the pelvic peritoneum and the surfaces of various organs, with the uterosacral ligaments, rectouterine pouch, and the lower serous layer of the uterine posterior wall being the most common sites. In the early stages, scattered purple-brown hemorrhagic spots or granular nodules can be observed locally. As the disease progresses, adhesions may form between the posterior wall of the uterus and the anterior wall of the rectum, resulting in a shallow or obliterated rectouterine pouch. Involvement of the fallopian tube serosal layer is common, while the mucosal layer is less frequently affected. Tubal adhesions and twisting can impair normal peristalsis, and severe cases may result in tubal obstruction, contributing to infertility associated with endometriosis.

Peritoneal endometriosis can be further divided into:

- Pigmented Lesions: These are the classic blue-purple or brown ectopic nodules on the peritoneum, which are relatively easy to identify during surgery.

- Non-Pigmented Lesions: These represent early-stage lesions of ectopic endometrial tissue, which are more common and exhibit greater growth activity compared to pigmented lesions. Non-pigmented lesions are highly variable in appearance and can be further classified into red lesions and white lesions based on their gross morphology. Red lesions are rich in blood vessels and composed of endometrial glands or stromal cells, while white lesions are composed of connective tissue that forms after the absorption of hemorrhagic material.

Deep Infiltrating Endometriosis (DIE)

This subtype refers to endometriosis with lesions infiltrating to a depth of ≥5 mm. Commonly involved sites include the uterosacral ligaments, rectouterine pouch, vaginal fornix, rectovaginal septum, and the walls of the rectum or colon. The bladder wall and ureters may also be affected.

Endometriosis in Other Sites

Examples include scar endometriosis (e.g., lesions occurring at abdominal wall or perineal incision sites) and rare distant cases of endometriosis affecting the lungs or pleura.

Microscopic Examination

Typical ectopic endometrial tissue exhibits the presence of four components under the microscope: endometrial glands, stromal cells, fibrin, and red blood cells or hemosiderin-laden macrophages. Repeated bleeding may damage these structures, making them difficult to detect and leading to cases where clinical symptoms are suggestive of endometriosis but histological evidence is insufficient. The presence of even small numbers of endometrial stromal cells or hemosiderin-laden macrophages under the microscope is sufficient to confirm the diagnosis of endometriosis. Additionally, endometrial glands and stromal cells identified in histologically normal peritoneal tissue are referred to as microscopic endometriosis, with an incidence rate of approximately 10%–15%.

Clinical Presentation

The clinical manifestations of endometriosis vary greatly depending on the individual and the location of the lesions. Symptoms are closely linked to the menstrual cycle, although 25% of patients may experience no symptoms.

Symptoms

Lower Abdominal Pain and Dysmenorrhea

These are the primary symptoms of endometriosis and may present as dysmenorrhea, chronic pelvic pain, dyspareunia, or acute abdominal pain.

Dysmenorrhea

Dysmenorrhea is typically secondary and progressive. Pain often begins 1–2 days before menstruation, peaks on the first day of menstruation, and is localized to the lower abdomen and lumbosacral area. Pain may radiate to the perineum, anus, or thighs. The severity of pain is not necessarily proportional to the size of the lesions. For example, patients with severe adhesions from ovarian endometriotic cysts may not experience pain, while small scattered pelvic lesions can cause unbearable pain. However, dysmenorrhea is not a required diagnostic feature, as 27%–40% of patients do not experience this symptom.

Chronic Pelvic Pain (CPP)

Some patients experience chronic pelvic pain that worsens during menstruation.

Dyspareunia

This is often seen in cases where ectopic lesions are located in the rectouterine pouch or where local adhesions cause fixed retroversion of the uterus. This typically presents as deep dyspareunia, with the most pronounced pain occurring before menstruation.

Acute Abdominal Pain

In cases of large ovarian endometriotic cysts, significant rupture may cause cyst contents to leak into the pelvic and abdominal cavities, resulting in sudden and severe abdominal pain, accompanied by nausea, vomiting, and rectal pressure. Ruptures typically occur around the time of menstruation and are often preceded by sexual activity or other situations that increase intra-abdominal pressure.

Infertility

The infertility rate among patients with endometriosis is as high as 50%. Infertility may result from various factors, including extensive pelvic adhesions and anatomical abnormalities that lead to fallopian tube obstruction or distortion, impairing sperm-egg interaction and transport. Altered pelvic microenvironments and immune dysfunction can increase anti-endometrial antibodies, disrupting endometrial metabolism and physiological functions. Ovarian dysfunction may lead to ovulation disorders or poor luteal formation. Additionally, the natural miscarriage rate among endometriosis patients reaches 40%. Luteinized unruptured follicle syndrome (LUFS) also has a high prevalence among patients with endometriosis.

Menstrual Irregularities

Approximately 15%–30% of patients experience increased menstrual volume, prolonged menstruation, persistent spotting, or premenstrual spotting. These symptoms may be linked to ovarian parenchymal lesions, anovulation, luteal dysfunction, or coexisting conditions such as adenomyosis or uterine fibroids.

Other Specific Symptoms

Endometriotic lesions outside the pelvic region may exhibit localized cyclic pain, bleeding, and lump formation, accompanied by related symptoms. Intestinal endometriosis may cause abdominal pain, diarrhea, constipation, or cyclic rectal bleeding, with severe cases resulting in intestinal obstruction due to mass compression. Bladder endometriosis may present with dysuria, frequent urination, or hematuria, particularly around menstruation. Lesions invading or compressing the ureters may cause ureteral stricture or obstruction, leading to flank pain, hematuria, hydronephrosis, or secondary renal atrophy. Respiratory tract endometriosis may exhibit hemoptysis or pneumothorax during menstruation. Patients with scar endometriosis often experience cyclic pain and swelling at scar sites months or years after caesarean section or perineal episiotomy, with symptoms worsening over time.

Physical Signs

In cases of typical pelvic endometriosis, bimanual or combined bimanual-rectovaginal examinations may reveal specific signs. Findings may include a fixed retroverted uterus and tenderness in nodules felt in the rectouterine pouch, uterosacral ligaments, or lower posterior uterine wall. Cystic-solid masses with limited mobility may also be palpable in one or both adnexa. When cyst rupture occurs, signs of peritoneal irritation may be present. If the lesion involves the rectovaginal space, palpable nodules or localized tenderness may be observed on the posterior vaginal wall, sometimes with visible small protrusions or purple-blue spots in the affected area.

Diagnosis

Endometriosis is often associated with diagnostic delays, which can exacerbate the condition, further impact treatment and prognosis, and reduce the patient's quality of life. Therefore, early diagnosis of endometriosis is crucial. Current diagnostic approaches include clinical diagnosis and surgical diagnosis. Clinical diagnosis plays a vital role in early intervention for endometriosis. A preliminary diagnosis can be made based on clinical presentations, while imaging studies and biomarker assessments provide supportive evidence. A definitive diagnosis can be achieved through laparoscopy.

Clinical Presentation

Endometriosis can be clinically diagnosed in reproductive-age women presenting with secondary and progressively worsening dysmenorrhea, infertility, chronic pelvic pain, or dyspareunia. The diagnosis may be supported by gynecological examination findings, such as palpable tender nodules in the pelvis.

Imaging Studies

Ultrasound is an important diagnostic tool for identifying ovarian endometriotic cysts, as well as bladder and rectal endometriosis. It can help determine the location, size, and shape of ectopic cysts. Endometriotic cysts often appear round or oval and show adhesions to surrounding organs, particularly the uterus. The cyst walls are typically thick and rough, with fine flocculent echoes visible inside. Pelvic CT and MRI are valuable for evaluating the extent of deep endometriotic lesions involving the bowel, bladder, or ureters. However, they are not first-line diagnostic methods. In cases of early-stage endometriosis, imaging findings are often nonspecific or absent, meaning a normal ultrasound or MRI does not rule out endometriosis.

Biomarker Assessment

Currently, no peripheral blood or endometrial biomarker is available for the accurate diagnosis of endometriosis. Patients with the condition may have elevated serum levels of carbohydrate antigen 125 (CA125), which are more pronounced in severe cases. CA125 can be useful for identifying advanced endometriosis or suspected deep lesions. However, CA125 levels may also be elevated in other conditions, such as ovarian cancer or pelvic inflammatory disease, and its sensitivity and specificity for diagnosing endometriosis are relatively low. Therefore, CA125 is not considered a standalone diagnostic marker but can assist in monitoring disease progression, evaluating treatment effectiveness, and predicting recurrence.

Laparoscopy

Laparoscopy is the internationally recognized gold standard for the surgical diagnosis of endometriosis. It allows for a comprehensive evaluation of the location and extent of the lesions and enables pathological confirmation through biopsy of suspicious tissue. Laparoscopy also facilitates the determination of clinical staging and subtypes of endometriosis during surgery, as well as assessment of fertility potential.

Other Specialized Examinations

In cases suspected of bladder or intestinal endometriosis, cystoscopy or colonoscopy with tissue biopsy can confirm the diagnosis.

Differential Diagnosis

Endometriosis may be confused with the following conditions and should be differentiated accordingly:

Ovarian Malignancies

Early ovarian cancer is often asymptomatic; when symptoms appear, they typically include persistent abdominal pain and distension. The disease progresses rapidly, with a poor general condition. Ultrasound often shows mixed cystic-solid or solid masses. Serum levels of CA125 and human epididymis protein 4 (HE4) are usually significantly elevated. Laparoscopy or exploratory laparotomy can aid in differentiation.

Pelvic Inflammatory Masses

A history of acute or recurrent pelvic infections is often present. Pain lacks a cyclical pattern and may include persistent lower abdominal discomfort, often accompanied by fever and elevated white blood cell counts. Symptoms usually improve with antibiotic therapy.

Adenomyosis

The dysmenorrhea associated with adenomyosis resembles that of endometriosis but tends to be localized to the midline of the lower abdomen and is often more severe. The uterus is usually uniformly enlarged and firm, with significant tenderness during menstruation. Adenomyosis often coexists with endometriosis.

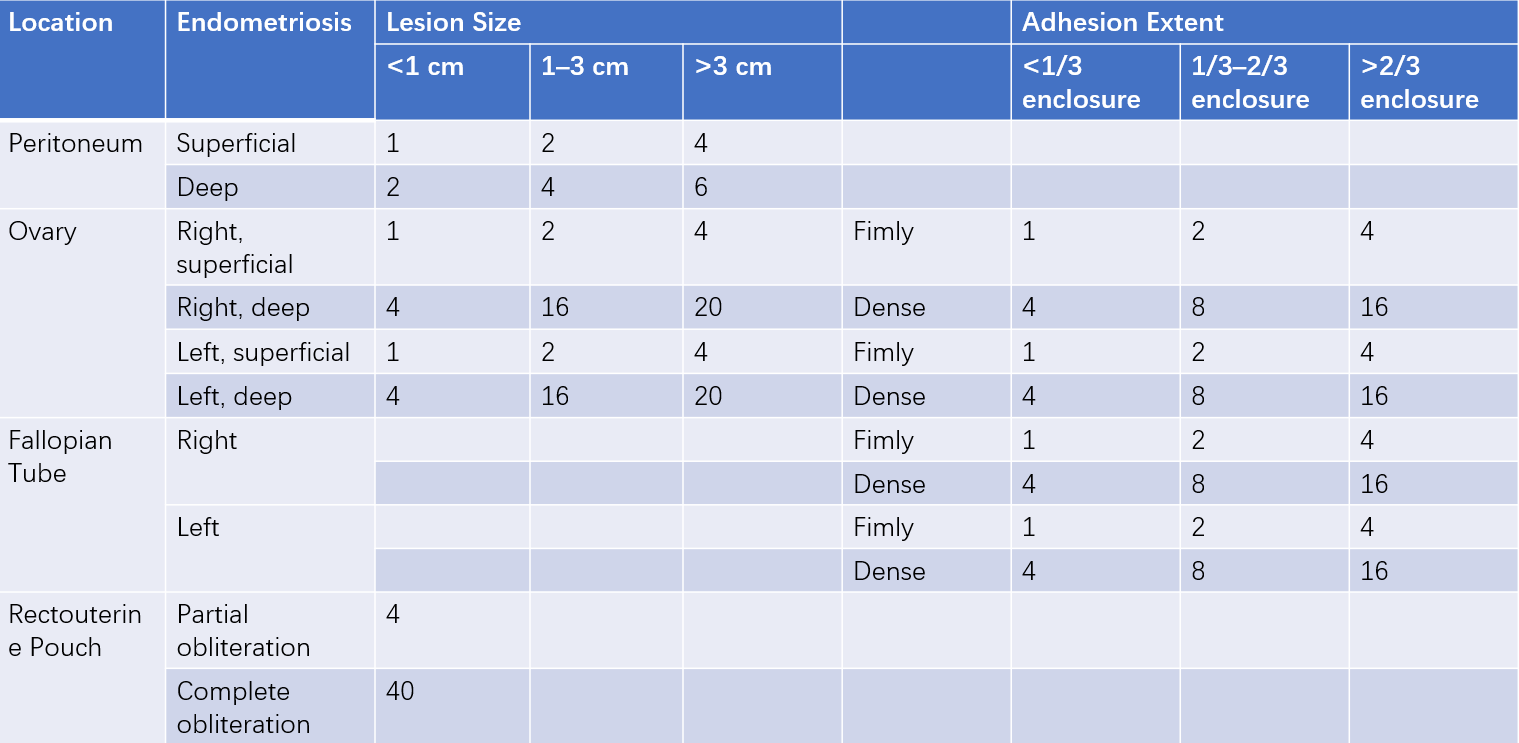

Clinical Staging

The revised staging system proposed by the American Society for Reproductive Medicine (ASRM) is currently used for endometriosis staging. Initially introduced in 1985 and revised in 1997, this staging system relies on laparoscopic or exploratory surgical findings. Detailed observation of lesion location, number, size, and degree of adhesions is required, followed by scoring. The staging system is helpful for assessing the severity of the disease, selecting appropriate treatment plans, accurately comparing and evaluating the efficacy of different treatments, and predicting patient prognosis.

Table 1 Revised ASRM staging of endometriosis (1997) (Units: points)

Treatment

The treatment goals for endometriosis include eliminating lesions, alleviating pain, promoting fertility, and reducing recurrence. The treatment principles involve individualized approaches based on the patient's age, symptoms, lesion location and extent, and fertility aspirations. Early empirical pharmacological treatment can begin following a clinical diagnosis. The selection of surgical indications, appropriate timing, and surgical techniques should consider preserving ovarian function and fertility. Postoperative comprehensive treatment is used to prevent recurrence, along with regular follow-ups and vigilance for malignant transformation. Long-term management of endometriosis is essential.

Pharmacological Treatment

Pharmacological treatment is suitable for patients with pelvic pain without infertility or adnexal masses, patients with adnexal masses less than 4 cm in diameter, or as preoperative therapy to shrink and soften lesions, facilitating surgery and minimizing surgical extent.

Nonsteroidal Anti-Inflammatory Drugs (NSAIDs)

NSAIDs are anti-inflammatory, antipyretic, and analgesic drugs that do not contain corticosteroids. Their primary mechanism involves inhibiting prostaglandin synthesis to alleviate pain. Administration is based on need with an interval of no less than six hours. Gastrointestinal side effects are common, with rare cases of liver and kidney dysfunction. Long-term use requires caution regarding the potential for gastric ulcers.

Progestins

Synthetic high-efficiency progestins suppress pituitary secretion of gonadotropins, inducing a low-estrogen state without cyclic fluctuations. Combined with endogenous estrogen, they cause high-progestin amenorrhea and decidualization of the endometrium, mimicking pregnancy. Various formulations have similar efficacy. Dienogest (2 mg/day, oral), medroxyprogesterone acetate (30 mg/day, oral), dydrogesterone (10–20 mg/day, oral, taken from day 5 to day 25 of the menstrual cycle), and the levonorgestrel-releasing intrauterine system (LNG-IUS) are commonly used. Side effects include nausea, mild depression, fluid retention, weight gain, and irregular vaginal spotting. Dienogest is preferred for long-term management due to its low daily dose, minimal impact on liver and kidney function and metabolism, and good tolerability.

Oral Contraceptives

Oral contraceptives were among the earliest hormonal treatments for endometriosis. They lower pituitary gonadotropin levels and directly affect endometrial and ectopic endometrial tissue, causing atrophy and reducing menstrual flow. Prolonged continuous use leads to artificial amenorrhea resembling pregnancy ("pseudopregnancy therapy"). This approach is ideal for mild endometriosis. Commonly, low-dose combined estrogen-progestin pills are taken daily for six to nine months. Side effects include nausea and vomiting, with attention warranted concerning the risk of thrombosis.

Gonadotropin-Releasing Hormone Agonists (GnRH-a)

GnRH-a initially stimulates short-term gonadotropin release (LH and FSH) from the pituitary, followed by sustained suppression of gonadotropin secretion, significantly reducing ovarian hormone levels and inducing temporary amenorrhea. This method, referred to as "medical oophorectomy," uses drugs such as leuprolide (3.75 mg injected subcutaneously on day 1 of menstruation, repeated every 28 days for three to six cycles) and goserelin (3.6 mg, similar administration). Amenorrhea typically begins in the second month of treatment, relieving dysmenorrhea. Ovulation usually resumes shortly after discontinuation. Side effects include menopausal symptoms such as hot flashes, vaginal dryness, decreased libido, and bone loss, which subside after treatment cessation. Bone loss, however, takes about a year to recover. Add-back therapy with estradiol valerate (0.5–1.0 mg) combined with medroxyprogesterone acetate (2 mg daily) or tibolone (1.25 mg/day) during GnRH-a treatment for 3–6 months can help prevent vascular symptoms and bone loss associated with hypoestrogenism.

Progesterone Receptor Antagonists

Mifepristone has five times the affinity for uterine progesterone receptors compared to progesterone itself. It exhibits strong antiprogestogenic effects and reduces lesions by inducing amenorrhea. The dosage typically ranges from 25–100 mg/day. Long-term efficacy needs further validation.

Androgen Derivatives

Agents such as gestrinone and danazol are rarely used in clinical practice. Gestrinone, a 19-nortestosterone steroid, has anti-progestin, moderate anti-estrogen, and anti-gonadotropic effects, inducing a pseudo-menopausal state. It is administered twice weekly (2.5 mg per dose), starting on the first day of menstruation, with a treatment course of six months. Danazol, a synthetic derivative of 17α-ethynyl testosterone, suppresses FSH and LH surges, reducing ovarian steroid hormone synthesis and causing endometrial atrophy and amenorrhea.

Surgical Treatment

Surgery is indicated for cases unresponsive to medication, infertility, or adnexal masses with diameters ≥4 cm. Laparoscopic surgery is the preferred method. Surgical options include:

Fertility-Preserving Surgery

This involves excision or destruction of all visible ectopic lesions, adhesiolysis, and restoration of normal anatomy while preserving the uterus and at least part of the ovarian tissue. This approach is suitable for younger patients with infertility needs or resistance to medical treatment. For endometriotic ovarian cysts, especially in patients over 35 years old, cystectomy is recommended. Although ovarian reserve may decline after surgery, preoperative evaluation of potential impacts on ovarian reserve is necessary. Surgical techniques should aim to protect normal ovarian tissue. Postoperative recurrence rates are high (approximately 40%). Patients with fertility plans are advised to attempt conception within 6–12 months post-surgery, as this is the optimal period for pregnancy. If fertility is not immediately desired, medication and long-term management should follow. Repeated surgeries for recurrent cysts are generally discouraged.

Ovarian Function-Preserving Surgery

This procedure removes pelvic lesions and the uterus while retaining part of the ovaries. It is recommended for patients with stage III or IV endometriosis, significant symptoms, and no fertility desires under 45 years old. The recurrence rate is approximately 5%.

Radical Surgery

This approach removes the uterus, bilateral adnexa, and all pelvic ectopic lesions. It is suitable for severe cases in patients over 45 years old. Recurrence is rare if estrogen replacement therapy is not used post-surgery.

Treatment for Other Special Cases of Endometriosis

Management of Endometriosis-Associated Infertility

For patients with endometriosis and infertility, a comprehensive infertility evaluation is necessary following established diagnostic pathways, including:

- Assessment of disease severity (previous treatments, size of ovarian cysts, and presence of adenomyosis).

- Evaluation of fertility potential (age, antral follicle count, anti-Müllerian hormone levels, and baseline endocrine parameters).

- Testing for tubal patency.

- Assessment of ovulatory function.

- Semen analysis of the male partner.

Treatment approaches include:

- For patients older than 35 years with infertility, abnormalities in the male partner's semen, gamete transport issues, or ovarian suspected endometriotic cysts, in-vitro fertilization and embryo transfer (IVF-ET) is recommended directly.

- For patients aged 35 years or younger without male factor infertility, combined laparoscopy and hysteroscopy followed by the evaluation of the Endometriosis Fertility Index (EFI) is indicated. Patients with an EFI score ≥5 may be monitored for six months post-laparoscopy, offering an opportunity for natural conception. Those with an EFI score ≤4 are advised to proceed directly with IVF-ET.

Management of Recurrent Endometriosis

Recurrent endometriosis is characterized by the reappearance of clinical symptoms or lesions after initial resolution through standard surgical or pharmacological treatment. Symptoms or lesion severity return to pre-treatment levels or worsen. Recurrence rates average at 20% within two years and 50% within five years. High-risk factors for recurrence include younger age, history of prior treatment for endometriosis (medication or surgery), advanced-stage disease, severe dysmenorrhea, incomplete initial surgery, deep infiltrating endometriosis (DIE), absence of postoperative hormonal therapy, and coexisting adenomyosis.

Treatment approaches include:

- For recurrent endometriosis patients with fertility desires, conservative pharmacological treatment is recommended to preserve ovarian reserve, provided malignancy is excluded. Repeated surgeries should be avoided due to the potential for further reduction in ovarian reserve.

- For patients without fertility desires, recurrent pain following surgery is typically addressed with pharmacological treatment. In cases of recurrent endometriotic ovarian cysts, early progestin therapy can delay subsequent surgeries. For patients over 45 years of age or those whose disease progresses despite medication and without fertility requirements, hysterectomy with bilateral salpingo-oophorectomy may be considered.

Management of Malignant Transformation in Endometriosis

The risk of malignant transformation in endometriosis is approximately 0.5%–1%. Most malignancies arise from the glandular epithelium, predominantly affecting the ovaries. Common histological types include endometrioid carcinoma and clear cell carcinoma of the ovary.

The following clinical scenarios warrant vigilance for potential malignant transformation:

- Age ≥45 years.

- Postmenopausal status.

- Disease duration of 10 years or more.

- Endometriosis-associated infertility.

- Changes in the pattern of pain.

- Ovarian cysts with a diameter ≥8 cm.

- Imaging findings suggesting cystic masses with solid or papillary structures, rich blood flow, and low resistance.

- Coexisting endometrial pathologies.

Treatment follows the principles for ovarian cancer management. Patients with malignancies arising from endometriosis tend to be younger, have earlier-stage disease, and generally have a better prognosis compared to ovarian cancer unrelated to endometriosis.

Prevention

The exact cause of endometriosis remains unclear, so preventive measures are limited. The following strategies may help reduce the risk of developing the condition:

Prevention of Retrograde Menstruation

Early identification and treatment of conditions leading to menstrual blood retention, such as congenital obstructive reproductive tract anomalies, secondary cervical adhesions, or vaginal stenosis, are advised.

Pharmacological Contraception

Oral contraceptives can suppress ovulation, promote endometrial atrophy, and reduce the risk of endometriosis. It may be a suitable option for individuals with a family history of endometriosis or those prone to ectopic implantation.

Prevention of Iatrogenic Endometrial Dissemination

Minimizing repeated uterine surgeries is important. For intrauterine procedures, care should be taken to avoid suture passage through the endometrial layer, and the abdominal wall incision should be irrigated following surgery. Tubal patency tests should not be performed premenstrually to avoid introducing endometrial fragments into the peritoneal cavity. Surgeries involving the cervix or vagina should also be avoided before menstruation to prevent implantation of endometrial fragments into surgical wounds. During suction curettage for induced abortion, intrauterine pressure should not be excessively high, and sudden withdrawal of the suction catheter should be avoided.

Prevention of Recurrence

Postoperative pharmacological therapy, such as combined oral contraceptives (COC), progestins, GnRH agonists (recommended for six months), and the LNG-IUS, can be effective in reducing the risk of recurrence.