Pelvic inflammatory disease (PID) refers to a group of infectious conditions affecting the upper female reproductive tract, primarily including endometritis, salpingitis, tubo-ovarian abscess (TOA), and pelvic peritonitis. The inflammation may be confined to a specific site or involve multiple locations simultaneously, with salpingitis and salpingo-oophoritis being the most common. PID primarily occurs in sexually active women of reproductive age and is rare in premenarchal, sexually inactive, and postmenopausal women. When it does occur in these populations, it is often due to the spread of inflammation from adjacent organs. If left untreated or inadequately treated, PID can lead to infertility, tubal pregnancy, chronic pelvic pain, and recurrent infections, significantly impacting female reproductive health.

Natural Defense Mechanisms of the Female Reproductive Tract

The anatomical, physiological, biochemical, and immunological characteristics of the female reproductive tract provide robust natural defenses against infection. In healthy women, although various microorganisms exist in the vaginal environment, an ecological balance is typically maintained, which prevents inflammatory responses from occurring.

Anatomical and Physiological Characteristics

The labia majora naturally remain closed, covering the vaginal introitus and external urethral orifice.

The contraction of pelvic floor muscles keeps the vaginal introitus closed, and the anterior and posterior vaginal walls remain in close contact. This prevents external contamination, safeguards the normal vaginal microbiota, and maintains vaginal ecological balance, thereby inhibiting the growth of other bacteria.

The internal cervical os is tightly closed, and the endocervical canal is lined with a single layer of columnar epithelium that secretes mucus. The mucosa features folds, ridges, or crypts, which increase the overall mucosal surface area. The endocervical canal secretes a large quantity of mucus that forms a jelly-like mucus plug, acting as a mechanical barrier to prevent upper reproductive tract infections.

The menstrual shedding of the endometrium in women of reproductive age serves as a mechanism for eliminating infections from the uterine cavity.

The ciliary movements of epithelial cells lining the fallopian tubes, which direct toward the uterine cavity, along with tubal peristalsis, act as barriers against the upward migration of pathogens.

Biochemical Characteristics

The cervical mucus plug contains lactoferrin and lysozyme, which inhibit the invasion of pathogens into the endometrium. Both endometrial and tubal secretions also contain lactoferrin and lysozyme, which help eliminate any pathogens that may occasionally enter the uterine cavity or fallopian tubes.

Mucosal Immune System of the Reproductive Tract

The mucosa of the reproductive tract, including the vaginal, endocervical, and endometrial mucosa, contains variable numbers of lymphocytes, including T cells and B cells. Furthermore, neutrophils, macrophages, complement proteins, and various cytokines play significant immunological roles at the local level, providing effective defenses against infections.

When these natural defense mechanisms are disrupted, or when immune function is compromised, hormonal changes occur, or external pathogens invade, inflammation can develop.

Pathogens and Their Characteristics

The pathogens responsible for PID can have exogenous or endogenous origins, with the two often co-occurring. Mixed infections are common, where tissue damage caused by exogenous pathogens such as Chlamydia trachomatis or Neisseria gonorrhoeae facilitates secondary infection by endogenous aerobic or anaerobic bacteria.

Exogenous Pathogens

These are primarily sexually transmitted pathogens, including Chlamydia trachomatis and Neisseria gonorrhoeae. Other pathogens include cytomegalovirus, Trichomonas vaginalis, and Mycoplasma species.

Endogenous Pathogens

These originate from the normal vaginal flora and include both aerobic and anaerobic bacteria. Infections may involve only aerobes or only anaerobes but more commonly consist of mixed infections involving both types. Key aerobic and facultative anaerobic pathogens include Staphylococcus aureus, hemolytic streptococci, Escherichia coli, and Gardnerella vaginalis. Major anaerobic bacteria include Bacteroides fragilis, Peptococcus, Peptostreptococcus, and Prevotella species.

Infections caused by anaerobic bacteria are characterized by a high likelihood of forming pelvic abscesses, septic thrombophlebitis, and foul-smelling purulent discharge that contains gas bubbles.

Modes of Infection

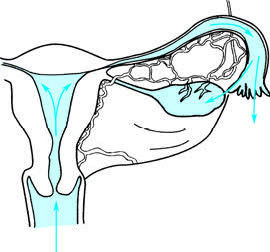

Ascension Along the Reproductive Tract Mucosa

Pathogens may ascend from the vulva and vagina or move from pathogens present in the vagina, spreading along the cervical mucosa, endometrium, and fallopian tube mucosa to reach the ovaries and abdominal cavity. This represents the primary route of infection for pelvic inflammatory disease (PID) outside of pregnancy or the postpartum period. Neisseria gonorrhoeae, Chlamydia trachomatis, and Staphylococcus are common pathogens that spread via this route.

Figure 1 Inflammation spreading upward through the mucosal pathway

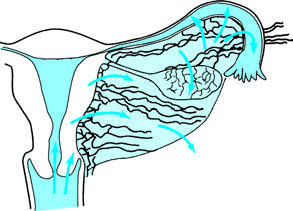

Lymphatic Spread

Pathogens can invade the pelvic connective tissue and other parts of the internal genitalia through lymphatic vessels at the site of trauma in the vulva, vagina, cervix, or uterine body. This is a primary mechanism for postpartum infections, post-abortion infections, and infections following the insertion of intrauterine devices (IUDs). Streptococcus, Escherichia coli, and anaerobic bacteria often spread through this pathway.

Figure 2 Inflammation spreading through the lymphatic system

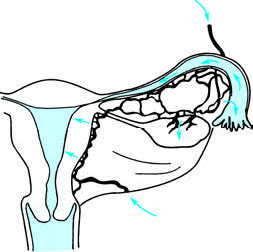

Hematogenous Spread

Pathogens may initially infect other organ systems before spreading to the reproductive tract through the bloodstream. This is the primary mode of dissemination for infections caused by Mycobacterium tuberculosis.

Figure 3 Inflammation spreading via hematogenous dissemination

Direct Spread

Infections from other abdominal organs can directly invade the internal genitalia. For example, appendicitis may result in right-sided salpingitis.

High-Risk Factors

Understanding high-risk factors is crucial for the accurate diagnosis and prevention of pelvic inflammatory disease.

Age

PID is most prevalent among women aged 25–44. Women of reproductive age are particularly susceptible, possibly due to factors such as frequent sexual activity and cervical columnar epithelium ectopy.

Sexual Activity

PID commonly occurs in sexually active women, especially those with early sexual debut, multiple sexual partners, frequent sexual activity, or partners with sexually transmitted infections.

Lower Reproductive Tract Infections

Conditions such as gonococcal cervicitis caused by Neisseria gonorrhoeae, chlamydial cervicitis caused by Chlamydia trachomatis, and bacterial vaginosis are closely associated with the development of PID.

Post-Intrauterine Procedures

Uterine cavity procedures such as curettage, tubal flushing, hysterosalpingography, and hysteroscopy may lead to infections due to damage to the reproductive tract mucosa, bleeding, and necrosis, facilitating the ascension of endogenous pathogens from the lower reproductive tract.

Poor Sexual Hygiene

Practices such as intercourse during menstruation, the use of unclean menstrual pads, and insufficient personal hygiene increase the likelihood of pathogen invasion and subsequent inflammation. Frequent vaginal douching is also associated with a higher incidence of PID.

Inflammation of Adjacent Organs

Conditions such as appendicitis or peritonitis that spread to the pelvic region are typically caused by Escherichia coli.

History of Pelvic Inflammatory Disease

Extensive pelvic adhesions, tubal damage, and reduced tubal defenses caused by past PID episodes increase the risk of reinfection and acute exacerbation.

Pathology and Pathogenesis

Endometritis and Myometritis

The endometrium may exhibit hyperemia, edema, and inflammatory exudates. In severe cases, necrosis and detachment of the endometrium can form ulcers. Microscopically, extensive infiltration by leukocytes is observed, with the inflammation invading deeper tissues, leading to myometritis.

Salpingitis, Pyosalpinx, and Tubo-Ovarian Abscess

The inflammatory changes in the fallopian tubes vary depending on the pathogen and the route of transmission:

Ascending Infection via the Endometrium

This initially causes mucosal inflammation of the fallopian tubes, characterized by mucosal swelling, stromal edema, hyperemia, and massive neutrophil infiltration. Severe cases may result in degenerative changes or extensive shedding of the tubal epithelium, leading to mucosal adhesions and occlusion of the tubal lumen and fimbrial ends. The accumulation of purulent material in the tubal lumen forms pyosalpinx. Pathogens such as Neisseria gonorrhoeae, Escherichia coli, Bacteroides, and Prevotella not only directly damage the tubal epithelium but also release endotoxins like lipopolysaccharides, causing extensive ciliary loss and impairing tubal transport function. Cross-immune reactions triggered by Chlamydia-associated heat shock proteins may further damage the tubal mucosal structure and function, leading to widespread pelvic adhesions.

Lymphatic Dissemination via the Cervix

This mode primarily affects the serosal layer of the fallopian tubes through periglandular connective tissue, progressing to peri-salpingitis and then the muscular layer. Mucosal involvement may be mild or absent. Tubal interstitial inflammation often results in luminal narrowing due to thickening of the muscular wall, although the passage often remains intact. Mild cases exhibit slight hyperemia, swelling, and minimal thickening of the fallopian tube, while severe cases involve pronounced thickening, tortuosity, and extensive fibrino-purulent exudates, causing adhesions to surrounding tissues. Ovarian involvement usually occurs concurrently with inflamed fimbriae adhering to the ovary, resulting in peri-oophoritis, commonly referred to as adnexitis. Inflammation may invade the ovary through ovulation sites, leading to intraparenchymal ovarian abscesses. When pyosalpinx adheres to and perforates the inflamed ovary, this forms a tubo-ovarian abscess. Tubo-ovarian abscesses are often located behind the uterus, within the broad ligament posterior leaf, or in adhesions between the bowel segments. Rupture of the abscess into the rectum or vagina can cause a sudden relief of symptoms, while rupture into the peritoneal cavity results in diffuse peritonitis.

Pelvic Peritonitis

Severe infections of the pelvic reproductive organs often extend to the pelvic peritoneum, resulting in hyperemia, edema, and the presence of serofibrinous exudates. This may cause adhesions among pelvic organs. Accumulation of large amounts of purulent exudates within adhesion spaces can lead to scattered abscesses or localized pelvic abscesses, commonly in the recto-uterine pouch. These abscesses may rupture into the rectum or vagina, alleviating symptoms, or into the abdominal cavity, leading to diffuse peritonitis.

Pelvic Cellulitis

Pathogens spreading through lymphatic vessels into the pelvic connective tissue cause hyperemia, edema, and neutrophil infiltration. Parametritis is the most common form of pelvic cellulitis, which initially presents with local thickening, softening, and poorly defined boundaries, later spreading fan-shaped along the pelvic walls. Suppuration of the connective tissue can result in extraperitoneal abscesses that may spontaneously rupture into the rectum or vagina.

Sepsis

Sepsis is a life-threatening organ dysfunction caused by a dysregulated host response to infection. Severe cases of tubo-ovarian or pelvic abscesses may result in sepsis.

Perihepatitis

Perihepatitis involves inflammation of the hepatic capsule without damage to the liver parenchyma. It is commonly associated with Neisseria gonorrhoeae or Chlamydia infections. Hepatic capsule edema can cause right upper quadrant pain during inspiration. Purulent or fibrinous exudates may be present on the liver capsule. Early stages result in loose adhesions between the hepatic capsule and anterior abdominal peritoneum, while late stages form violin string-like adhesions. Perihepatitis occurs in 5–10% of salpingitis cases, presenting clinically as right upper quadrant pain following lower abdominal pain or concurrent lower and upper abdominal pain.

Clinical Presentation

The clinical manifestations of pelvic inflammatory disease (PID) vary depending on the severity and extent of the inflammation. Mild cases may be asymptomatic, while more severe cases can present with the following:

Symptoms

Lower Abdominal Pain and Increased Vaginal Discharge

These are the most common symptoms. Abdominal pain is typically persistent and worsens after physical activity or sexual intercourse.

Menstrual Abnormalities

Onset during menstruation may be associated with increased menstrual flow or prolonged menstrual periods.

Gastrointestinal Symptoms

When accompanied by peritonitis, symptoms such as loss of appetite, nausea, vomiting, abdominal distension, and diarrhea may occur. In cases involving abscesses in the posterior uterine region, rectal irritation symptoms, including diarrhea, tenesmus, and difficulty defecating, may be present.

Urinary Symptoms

Coexisting urinary tract infections may present with urgency, frequency, and dysuria. If an abscess forms anterior to the uterus, difficulty in urination may occur.

Systemic Symptoms

In severe cases, fever, high fever, chills, headache, fatigue, and other systemic symptoms may be observed.

Physical Signs

The presentation varies significantly among patients. Mild cases may exhibit no overt abnormalities, with gynecological examination revealing only cervical motion tenderness, uterine tenderness, or adnexal tenderness. Severe cases may present with acute systemic illness, including fever, tachycardia, and lower abdominal tenderness accompanied by rebound tenderness and muscle guarding. Abdominal distension and decreased or absent bowel sounds may also occur.

Gynecological examination may reveal purulent and foul-smelling vaginal discharge, cervical congestion, and edema. Cleaning the cervical os may reveal purulent discharge emanating from the cervical canal, indicating acute inflammation of the cervical mucosa or uterine cavity. Cervical motion tenderness, uterine enlargement with tenderness, restricted uterine mobility, and marked bilateral adnexal tenderness may be observed. In cases of isolated salpingitis, thickened fallopian tubes with prominent tenderness may be palpable. With pyosalpinx or tubo-ovarian abscess, palpable adnexal masses with marked tenderness and restricted mobility are often noted.

Parametritis may present as unilateral or bilateral thickening of the parametrium or pronounced hypersensitivity and thickening of the uterosacral ligaments. In cases of low-lying pelvic abscesses, posterior fornix tenderness may be significant. Adnexal masses with fluctuation may be palpated in the rectouterine pouch, and bimanual rectovaginal examination offers additional insights into the presence of pelvic abscess and its relationship with nearby organs.

Diagnosis

Diagnosis is generally based on the patient’s medical history, symptoms, physical signs, and laboratory test results. Because of the variable clinical presentations of PID, the accuracy of clinical diagnosis is relatively limited. Compared to laparoscopic findings, the positive predictive value of a clinical diagnosis is approximately 65%–90%. As no single characteristic symptom, sign, or highly sensitive and specific laboratory test currently exists for PID, early clinical diagnosis is challenging. Diagnostic delays can contribute to long-term complications.

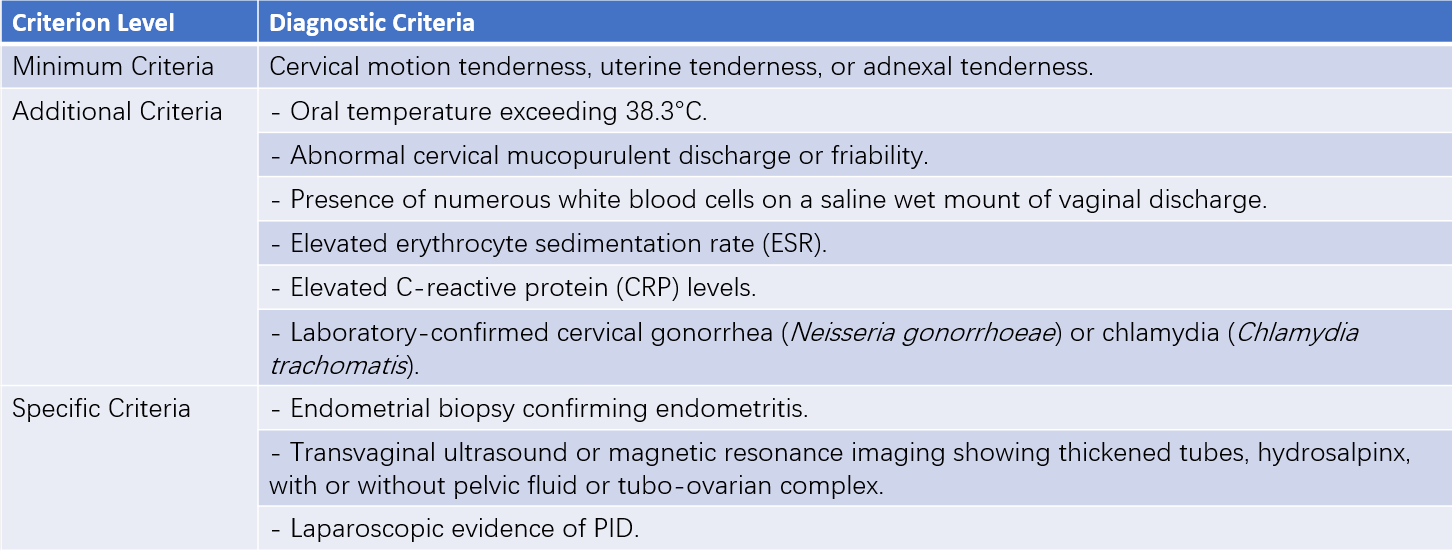

The diagnostic criteria for PID established by the U.S. Centers for Disease Control and Prevention (CDC) in 2021 aim to raise awareness of PID in young women presenting with abdominal pain and/or abnormal vaginal discharge or irregular vaginal bleeding. These criteria facilitate further evaluation of suspected cases and prompt treatment, thereby reducing the likelihood of complications.

Table 1 Diagnostic criteria for pelvic inflammatory disease (PID)

Minimal Diagnostic Criteria

For sexually active young women or high-risk individuals for sexually transmitted infections (STIs) presenting with lower abdominal pain, a clinical diagnosis of PID may be considered if no other cause for the symptoms is identified and minimal diagnostic criteria are met upon gynecological examination. In such cases, antimicrobial therapy can be initiated.

Additional Diagnostic Criteria

Additional diagnostic criteria may increase specificity. Most PID patients present with mucopurulent endocervical discharge, or vaginal saline wet mount slides reveal a significant number of leukocytes. If cervical discharge appears normal and no leukocytes are observed microscopically in vaginal specimens, the diagnosis of PID requires re-evaluation, and alternative causes of abdominal pain should be considered. Vaginal discharge testing can also identify concurrent infections, such as bacterial vaginosis or trichomoniasis.

Specific Diagnostic Criteria

Specific criteria, while diagnostic for PID, often rely on invasive procedures and are generally reserved for selected cases. Ultrasonography (US) and magnetic resonance imaging (MRI) are non-invasive alternatives, but findings from laparoscopic investigations remain the gold standard. The diagnostic criteria for salpingitis via laparoscopy include:

- Significant hyperemia of the fallopian tube surface.

- Edema of the fallopian tube wall.

- Purulent exudates on the fimbrial or serosal surface of the fallopian tube.

Laparoscopy offers high diagnostic accuracy for salpingitis and allows direct sampling of infectious exudates for microbiological culture. However, it has certain limitations in routine clinical practice. Diagnostic sensitivity is reduced for mild salpingitis, and laparoscopy lacks diagnostic utility for isolated endometritis. Therefore, not all suspected PID cases require laparoscopic evaluation.

Microbiological testing to confirm the causative pathogen is recommended following a PID diagnosis. Endocervical discharge and posterior fornix aspirated fluid can be analyzed using smears, cultures, and nucleic acid amplification tests. Samples of infectious exudate can also be obtained via exploratory laparotomy or laparoscopy for culture and antibiotic susceptibility testing. Gram staining may be used on smear preparations to identify bacterial morphology and guide empirical antimicrobial therapy. Bacterial cultures and susceptibility testing provide data to select optimal antimicrobial agents. In addition to pathogen testing, clinical features, medical history (e.g., high-risk sexual activity), and epidemiological context can assist in the preliminary identification of causative organisms.

Differential Diagnosis

PID needs to be distinguished from other acute abdominal emergencies, including acute appendicitis, ruptured or aborted tubal pregnancy, and ovarian cyst torsion or rupture.

Treatment

The primary approach to treatment involves antimicrobial therapy, with surgical intervention adopted in necessary cases. Antimicrobial therapy aims to eradicate pathogens, alleviate symptoms and signs, and reduce the likelihood of complications. With prompt and appropriate antimicrobial treatment, the vast majority of pelvic inflammatory disease (PID) cases can be completely cured. The principles of antimicrobial therapy include timeliness, broad-spectrum coverage, and individualized care:

- Timely administration of antimicrobial therapy is essential, with treatment initiated immediately after diagnosis. Starting therapy within 48 hours of diagnosis significantly lowers the risk of long-term complications associated with PID.

- Broad-spectrum antimicrobials are preferred, as PID often involves polymicrobial infections. Selected medications should cover all potential pathogens, including Neisseria gonorrhoeae, Chlamydia trachomatis, Mycoplasma, anaerobes, and aerobes.

- Individualized treatment decisions should consider factors such as safety, efficacy, cost-effectiveness, and patient adherence. The choice between intravenous (IV) and non-IV routes depends on the severity of the disease. While antimicrobial selection based on culture and sensitivity testing is ideal, initial therapies are guided by local epidemiology and clinical features when specific test results are unavailable.

Non-Intravenous Treatment Regimens

Non-IV treatment may be suitable for patients with mild symptoms, stable general condition, and the ability to tolerate oral antimicrobials. Outpatient care, including oral or intramuscular antibiotics, is appropriate for such cases, provided follow-up is feasible.

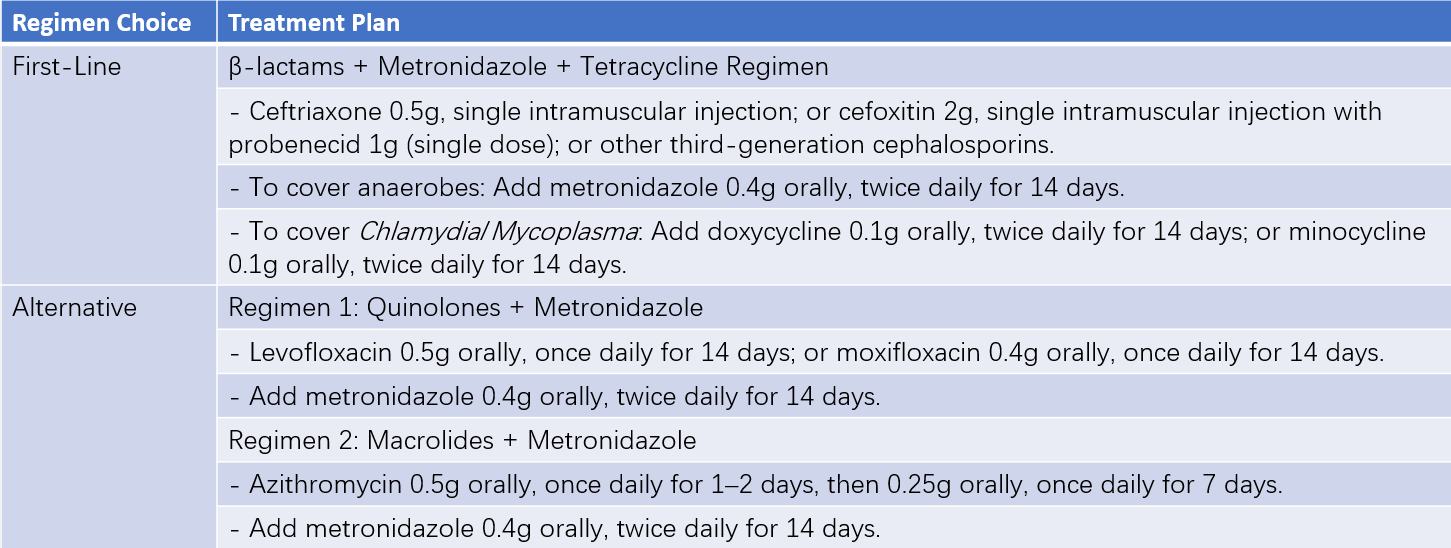

Table 2 Non-intravenous medication regimens for PID

Intravenous Treatment Regimens

IV therapy is indicated for patients with severe disease or poor general condition, when emergency surgical intervention cannot be ruled out, or in the presence of tubo-ovarian abscess, high fever, nausea, vomiting, or pregnancy. It is also indicated when outpatient treatment fails, oral antimicrobials cannot be tolerated, or when the diagnosis remains uncertain. Comprehensive inpatient management is preferred in such scenarios, with IV antimicrobials forming the cornerstone of therapy.

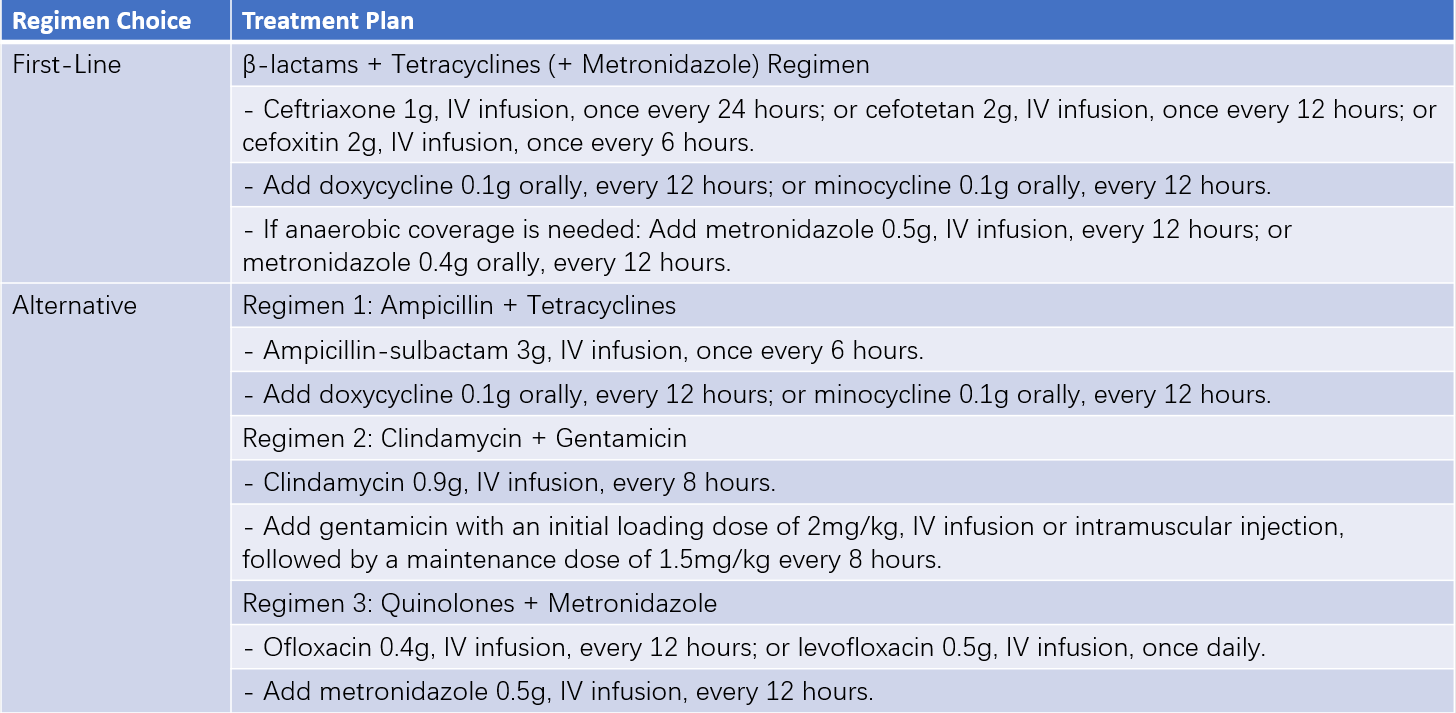

Table 3 Intravenous medication regimens for PID

Supportive Care

Measures include bed rest in a semi-recumbent position to localize inflammatory exudates in the rectouterine pouch, thereby limiting disease spread. Patients may receive high-calorie, high-protein, and high-vitamin liquid or semi-liquid diets, with fluid supplementation and correction of electrolyte imbalances and acid-base disturbances as required. Physical cooling methods are used to manage high fever.

Antimicrobial Therapy

Initial therapy typically involves IV administration for rapid effect. Following clinical improvement, IV antibiotics should be continued for at least 24 hours before transitioning to oral therapy, which should be continued for a total duration of at least 14 days.

For infections by Neisseria gonorrhoeae, cephamycins or cephalosporins are the first-line choices. Quinolones are no longer recommended due to the emergence of quinolone-resistant Neisseria gonorrhoeae strains. Exceptions may be made for populations where gonococcal prevalence is low, follow-up conditions are favorable, and cephalosporins are contraindicated (e.g., due to allergy). In these cases, quinolones may be considered, but gonococcal culture and susceptibility testing should be conducted prior to treatment initiation.

Image-Guided Aspiration Therapy

Image-guided aspiration therapy, in combination with antimicrobial therapy, is a treatment option for pelvic abscesses. Common imaging modalities include ultrasonography and CT. The approach (transabdominal, transvaginal, transrectal, or transgluteal) is determined by the abscess location. Techniques such as aspiration or catheter drainage may be employed. Indications for aspiration therapy include:

- Large abscesses and/or poor response to antimicrobial therapy.

- Residual yet localized masses after symptoms are alleviated through medication, requiring consolidation therapy.

- Recurrent abscesses or extensive adhesions due to multiple prior pelvic or abdominal surgeries, making surgical intervention challenging.

- Elderly patients with poor constitution or comorbid cardiac or pulmonary dysfunction that precludes surgical tolerance.

Care must be taken during the procedure to avoid injury to the bowel, major blood vessels, and critical organs.

Surgical Treatment

Surgical intervention is typically reserved for cases in which antimicrobial therapy proves inadequate to control tubo-ovarian or pelvic abscesses.

Surgical Indications

These include:

- Lack of response to medical therapy: Surgery should be performed if tubo-ovarian or pelvic abscesses fail to respond to medication within 48–72 hours, with persistent fever, worsening systemic toxicity, or increasing mass size, to prevent abscess rupture.

- Persistent or recurrent abscess: Surgery is indicated for persistent or recurrent masses after improvement with medical or aspiration therapy, to avoid acute exacerbation in the future.

- Abscess rupture: Signs such as sudden exacerbation of abdominal pain, chills, high fever, nausea, vomiting, abdominal distension, abdominal tenderness, or symptoms of septic shock warrant suspicion of abscess rupture. Delays in diagnosis and treatment of ruptured abscesses result in high mortality rates. Immediate exploratory surgery is required alongside antimicrobial therapy once rupture is suspected.

Surgical Approach and Scope

The surgical approach and extent of intervention should be based on the severity of symptoms, size of the abscess, extent of disease involvement, patient’s general condition, and reproductive considerations. Options include laparoscopy or open surgery, with procedures ranging from abscess drainage and ipsilateral adnexectomy to total hysterectomy with bilateral salpingo-oophorectomy.

Treatment of Sexual Partners

Sexual partners who had contact with the patient within 60 days prior to symptom onset should undergo evaluation and treatment. If the last sexual contact occurred more than 60 days prior, the most recent partner should be evaluated and treated. During the patient’s treatment for PID, unprotected sexual intercourse is discouraged.

Follow-Up

For patients undergoing antimicrobial therapy, follow-up should occur within 72 hours to assess for clinical improvement. Effective antimicrobial treatment is expected to result in symptom alleviation within this timeframe, such as a reduction in fever, abdominal tenderness, rebound tenderness, cervical motion tenderness, uterine tenderness, and adnexal tenderness. If symptoms fail to improve during this period, further evaluation and reassessment are required, and in some cases, laparoscopic exploration may be necessary.

For patients with infections caused by Chlamydia trachomatis or Neisseria gonorrhoeae, regardless of whether their sexual partners receive treatment, retesting is recommended 4–6 weeks and again at 3–6 months after treatment. If retesting does not occur at 3–6 months, it should be conducted during any visit within one year post-treatment.

Sequelae of Pelvic Inflammatory Disease (PID)

Untreated or improperly managed PID may lead to sequelae characterized by significant pathological changes, including tissue destruction, extensive adhesions, hyperplasia, and fibrosis. These changes manifest with various complications:

- Chronic Salpingitis: Tubal inflammation may cause fallopian tube obstruction or thickening.

- Tubo-Ovarian Adhesions: Formation of tubo-ovarian complexes through adhesions.

- Hydrosalpinx: The fimbrial end of the fallopian tube may become occluded, with serous exudates accumulating to form hydrosalpinx. Following the absorption of pus in conditions such as pyosalpinx or tubo-ovarian abscess, serous exudates may lead to hydrosalpinx or tubo-ovarian cyst formation.

- Pelvic Connective Tissue Involvement: Proliferation and thickening of the cardinal and uterosacral ligaments may occur. Extensive involvement can lead to uterine fixation.

Clinical Manifestations

Infertility

Tubal adhesion or obstruction can result in infertility, with a post-PID infertility rate of 20%–30%.

Chronic Pelvic Pain

Adhesions, scarring, and pelvic congestion caused by inflammation may lead to pelvic heaviness, pain, and lumbosacral aches, which often worsen with exertion, sexual activity, or around menstruation. Approximately 20% of patients develop chronic pelvic pain within 4–8 weeks after acute PID episodes.

Ectopic Pregnancy

The ectopic pregnancy risk following PID is 8–10 times higher than in unaffected women.

Recurrent PID

Structural damage to the fallopian tubes and reduced local immune defense mechanisms caused by previous PID increase the likelihood of recurrence when high-risk factors persist. Approximately 25% of patients with a history of PID experience recurrent episodes.

Physical Examination

Tubal Lesions

Thickened, cord-like fallopian tubes with mild tenderness may be palpable on one or both sides of the uterus.

Hydrosalpinx or Tubo-Ovarian Cyst

Cystic masses may be palpated in the pelvis on one or both sides, often with restricted mobility.

Pelvic Connective Tissue Lesions

The uterus may exhibit retroversion and retroflexion, with limited mobility or adhesive fixation. Unilateral or bilateral thickening and tenderness may be noted, with the uterosacral ligaments appearing thickened and hardened with associated tenderness.

Treatment

Treatment strategies for PID sequelae should be individualized:

Infertility

Assisted reproductive technologies are often necessary to achieve pregnancy.

Chronic Pelvic Pain

Effective treatments are limited; symptomatic management and other comprehensive approaches are considered. Conditions such as endometriosis must be ruled out before treatment.

Recurrent PID

In addition to antimicrobial therapy, surgical intervention may be required based on the specific clinical situation.

Prevention

Maintaining sexual hygiene can help reduce the incidence of sexually transmitted infections (STIs). Screening and treating women at high risk for Chlamydia trachomatis infections can lower the likelihood of developing PID.

Early treatment of lower genital tract infections is important.

Public health education plays a critical role in raising awareness about reproductive tract infections and emphasizing the importance of prevention.

Strict adherence to surgical indications in gynecological procedures, thorough preoperative preparation, and adherence to aseptic techniques during surgery can minimize infection risks.

Timely treatment of PID is essential to prevent subsequent complications and sequelae.