Uterine rupture refers to a tear in the uterine body or lower uterine segment occurring during pregnancy or labor. It is a rare but severe obstetric complication that can endanger both maternal and fetal life. Most cases occur during labor and constitute a major cause of maternal and perinatal mortality.

Etiology

History of Uterine Surgery (Scarred Uterus)

This is the most common cause of uterine rupture in recent years. Procedures such as cesarean section, myomectomy, cornual resection, removal of interstitial ectopic pregnancy, uterine reconstruction, focused ultrasound ablation, and repeated surgical abortions can result in uterine scarring. During late pregnancy or labor, increased intrauterine pressure may cause scar dehiscence or rupture. The risk increases with a history of postoperative infection, poor incision healing, or a short interdelivery interval.

Obstructed Labor

Though now less common clinically, obstructed labor still requires attention. It is typically associated with cephalopelvic disproportion, macrosomia, malpresentation, or fetal anomalies.

Uncoordinated or Excessive Uterine Contractions

These may be spontaneous or induced by uterotonic agents such as oxytocin or prostaglandins, leading to incoordinate or hypertonic contractions.

Obstetric Instrumental Injury

Use of forceps before full cervical dilation, mid- to high-forceps delivery, or breech extraction may result in cervical laceration extending to the lower uterine segment. Additionally, acquired factors such as placental accreta may contribute to rupture if attempts are made to forcibly remove an adherent placenta.

Other Causes

Congenital uterine anomalies resulting in thinning of the myometrium in localized areas may predispose to spontaneous rupture.

Clinical Manifestations

Uterine rupture primarily occurs during labor, though some cases arise in late pregnancy. Based on the extent of the tear, it can be classified as complete or incomplete. Most cases follow a progressive course, often starting with signs of impending rupture.

Fetal distress is a common manifestation, with most cases showing abnormal fetal heart rate patterns. Other typical signs include abnormal electronic fetal monitoring (EFM), persistent abdominal pain between contractions, abnormal vaginal bleeding, hematuria, cessation of contractions, abnormal presentation, changes in abdominal contour, maternal tachycardia, and hypotension.

Impending Uterine Rupture

This frequently occurs in women with prolonged labor or obstructed labor. Clinical signs may include:

- Rigid or spastic uterine contractions, maternal restlessness, rapid respiration and heart rate, and severe lower abdominal pain.

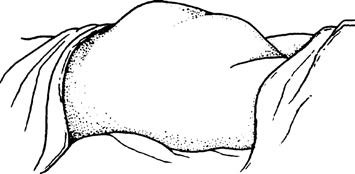

- Descent of the fetal presenting part is obstructed, leading to strong contractions and thickened, shortened upper uterine muscles, while the lower segment becomes thin and stretched, forming a pathological retraction ring that may ascend to or above the umbilicus with marked tenderness.

- Bladder compression and congestion causing dysuria and hematuria.

- Strong, frequent contractions may make it difficult to palpate fetal parts; fetal heart rate may become tachycardic, bradycardic, or inaudible.

Figure 1 Appearance of the abdomen during impending uterine rupture

Uterine Rupture

Incomplete Uterine Rupture

The myometrial layer is torn while the serosal layer remains intact, and there is no communication between the uterine and peritoneal cavities. The fetus and placental tissues remain within the uterus. This is most commonly seen in lower uterine segment cesarean scar dehiscence. Prodromal symptoms may be absent, with only localized tenderness over the rupture site. If the rupture extends to the uterine vasculature, acute hemorrhage may occur. If located in the uterine sidewall between the leaves of the broad ligament, a broad ligament hematoma may develop.

Complete Uterine Rupture

The rupture involves the entire uterine wall, including the serosal layer, resulting in communication between the uterine and abdominal cavities, with or without extrusion of the fetus or placenta. It usually occurs suddenly, with the mother experiencing a tearing sensation in the lower abdomen and an abrupt cessation of contractions. Abdominal pain may briefly subside, but continuous diffuse abdominal pain soon develops due to peritoneal irritation by amniotic fluid and blood, often accompanied by signs of hypovolemic shock.

There is marked abdominal tenderness and rebound pain. Fetal parts may be palpated easily through the abdominal wall, and the uterus may be displaced laterally. Fetal heart sounds and movements disappear. Vaginal bleeding may be present; the presenting part retracts upward, and the previously dilated cervix may close. If the rupture is low, the tear may be palpated via vaginal examination. These signs may follow symptoms of impending rupture. However, rupture at the site of a uterine body scar is often complete and may occur without typical prodromal symptoms. In cases of placenta percreta, rupture may present as persistent abdominal pain with abnormal fetal heart rate patterns, and it may be misdiagnosed as another acute abdominal condition or preterm labor.

Diagnosis

The diagnosis of typical uterine rupture is usually not difficult when based on medical history, clinical symptoms and signs, and imaging studies. In cases of uterine scar rupture where symptoms and signs are less apparent, a comprehensive assessment should be made by considering a history of previous cesarean section, tenderness over the lower uterine segment, abnormal fetal heart rate, elevation of the presenting part, and cervical regression. Ultrasonography can assist in diagnosis.

Differential Diagnosis

Uterine rupture often presents with abdominal pain, uterine tenderness, and abnormal fetal heart rate, and should be differentiated from conditions such as placental abruption, intrauterine infection, and fetal distress.

Management

The key to managing uterine rupture lies in early diagnosis and timely intervention.

Impending Uterine Rupture

Uterine contractions should be suppressed immediately, and surgery should be performed as soon as possible. General anesthesia may be used.

Uterine Rupture

While resuscitating for shock, surgical treatment should proceed without delay, regardless of fetal viability.

If the uterine tear is clean, of short duration, and there is no significant infection, uterine repair may be performed.

If the rupture is large, irregular, or associated with significant infection, a subtotal hysterectomy should be performed.

In cases where the rupture is extensive and involves the cervix, a total hysterectomy is indicated.

Broad-spectrum antibiotics should be administered in adequate dosage and duration before and after surgery to control infection. In cases of severe shock, stabilization and resuscitation should be carried out on-site whenever possible. If transfer to another facility is necessary, it should only be done after ensuring stable vital signs and adequate blood transfusion and fluid resuscitation.

Prevention

Adequate prenatal care should be provided, and patients with high-risk factors for uterine rupture should be admitted in advance for observation before labor.

Labor progress should be closely monitored, with vigilance for early signs of impending uterine rupture to enable prompt intervention.

The use of uterotonic agents should follow strict indications, with designated personnel monitoring and closely observing to prevent uterine hyperstimulation. For women with a scarred uterus undergoing trial of labor, continuous monitoring and the availability of emergency surgical capabilities are essential.

Obstetric indications and procedures for operative vaginal delivery should be strictly followed. After vaginal instrumental delivery, careful examination of the uterine cavity and birth canal is necessary to identify and repair any trauma.