Postpartum hemorrhage (PPH) refers to blood loss of ≥500 ml within 24 hours after vaginal delivery or ≥1,000 ml after cesarean section, or the presence of symptoms or signs of hypovolemia following blood loss. Severe postpartum hemorrhage refers to blood loss of ≥1,000 ml within 24 hours after delivery. According to literature, the incidence of postpartum hemorrhage ranges from 5% to 10%, but clinical estimation of blood loss is often lower than the actual volume, suggesting a higher true incidence. Postpartum hemorrhage is a common complication during childbirth and remains the leading cause of maternal mortality. In recent years, as understanding of the condition has improved, maternal mortality due to postpartum hemorrhage has declined significantly.

Etiology

The major causes of postpartum hemorrhage include uterine atony, placental factors, birth canal lacerations, and coagulation disorders. These factors may coexist, interact, or be causally related.

Uterine Atony

Uterine atony is the most common cause of postpartum hemorrhage. After fetal delivery, contraction and retraction of uterine muscle fibers lead to placental separation and closure of venous sinuses, thus controlling bleeding. Any factor impairing uterine muscle fiber contraction and retraction may result in uterine atony-related bleeding. Common contributing factors include:

- Systemic factors: Excessive maternal anxiety, fatigue, physical weakness, advanced maternal age, obesity, or chronic systemic diseases.

- Obstetric factors: Prolonged labor, precipitous delivery, placenta previa, placental abruption, hypertensive disorders during pregnancy, or intrauterine infection.

- Uterine factors:

- Overdistention of the uterus (e.g., multiple pregnancy, polyhydramnios, macrosomia);

- Uterine wall injury (e.g., prior cesarean section, myomectomy, high parity);

- Uterine abnormalities (e.g., fibroids, uterine malformations, uterine muscle degeneration).

- Medication-related factors: Excessive use of sedatives, anesthetics, or uterine relaxants during labor.

Placental Factors

Retained Placenta

Normally, the placenta is expelled within 15 minutes after delivery. If it is not expelled after 30 minutes, bleeding may occur. Common causes include:

- Bladder distention, which may trap a detached placenta inside the uterine cavity;

- Trapped placenta, in which a constriction ring at the internal cervical os prevents expulsion;

- Incomplete placental separation.

Placenta Accreta

This is classified by depth of invasion into adherent, invasive, and percreta types. Based on the area involved, it may be partial or complete. Partial accreta may result in partial detachment with exposed sinuses and significant bleeding. Complete accreta may involve minimal bleeding due to lack of separation. Placenta accreta can lead to severe postpartum hemorrhage and may cause uterine rupture. Percreta may further involve the bladder or rectum.

Partial Placental Retention

Retained cotyledons, accessory placenta, or membranes can interfere with uterine contraction and cause bleeding.

Birth Canal Lacerations

Lacerations of the birth canal during delivery may lead to postpartum hemorrhage. These include injuries to the perineum, vagina, and cervix. Severe cases may involve the vaginal fornix, lower uterine segment, or even pelvic walls, resulting in retroperitoneal or broad ligament hematomas, or uterine rupture. Contributing factors include instrumental delivery, macrosomia, precipitous labor, varicose veins of the birth canal, vulvar edema, or poor tissue elasticity.

Coagulation Disorders

Any primary or secondary coagulation dysfunction may result in postpartum hemorrhage. Primary thrombocytopenia, aplastic anemia, and liver disease may cause bleeding at surgical sites or the placental separation site due to impaired coagulation. Obstetric complications such as placental abruption, fetal demise, amniotic fluid embolism, and severe preeclampsia may lead to disseminated intravascular coagulation (DIC), resulting in massive uterine bleeding.

Clinical Manifestations

Postpartum hemorrhage typically presents as vaginal bleeding after fetal delivery. In severe cases, signs of hypovolemic shock or severe anemia may develop.

Vaginal Bleeding

Immediate bright red bleeding after fetal delivery suggests birth canal laceration.

Bleeding occurring a few minutes after delivery, appearing dark red, often indicates placental issues.

Heavy bleeding after placental delivery is suggestive of uterine atony or retained placental tissue.

Persistent bleeding after delivery of the fetus or placenta with non-clotting blood suggests a coagulation disorder.

When signs of hypovolemia are apparent but vaginal bleeding is minimal, hidden soft tissue injury (e.g., vaginal hematoma) should be suspected.

During cesarean section, postpartum hemorrhage typically presents as diffuse bleeding from the placental separation site, with some cases involving severe bleeding from the uterine incision.

Signs of Hypotension

Symptoms may include dizziness, pale complexion, rapid breathing, thready pulse, cold and clammy skin, and restlessness.

Diagnosis

The key to diagnosing postpartum hemorrhage lies in accurately measuring and estimating the amount of blood loss. Underestimation may result in missed opportunities for timely intervention. Accurate estimation of blood loss is essential to confirm the diagnosis, identify the cause, and initiate prompt management.

Estimation of Blood Loss

Several methods are commonly used:

Weighing Method

Blood loss (ml) = [wet weight of blood-soaked materials after delivery (g) – dry weight before use (g)] ÷ 1.05 (specific gravity of blood in g/ml).

Volumetric Method

Blood is collected in a container and then measured using a graduated measuring cup.

Surface Area Method

Blood loss is estimated based on the surface area of blood-soaked gauze.

Shock Index (SI) Method

Shock Index = Heart Rate / Systolic Blood Pressure.

In postpartum women, a normal SI ranges from 0.7 to 0.9, indicating stable blood volume.

- SI = 1.0 suggests blood loss of about 20% (1,000 ml);

- SI = 1.5 indicates 30% loss (1,500 ml);

- SI = 2.0 implies ≥50% loss (≥2,500 ml).

Hemoglobin Measurement

A decrease of 10 g/L in hemoglobin concentration is roughly equivalent to a loss of 400–500 ml of blood.

However, early in postpartum hemorrhage, hemoglobin levels may not accurately reflect true blood loss due to hemoconcentration.

It should be noted that each method has its limitations and may underestimate the actual blood loss. A combination of methods is often needed for a more reliable assessment. Additionally, the rate of bleeding serves as an important indicator of severity.

Determination of the Cause of Hemorrhage

The timing of vaginal bleeding in relation to delivery of the fetus and placenta, along with the volume of bleeding, may provide clues to the underlying cause. Causes of postpartum hemorrhage often overlap or contribute to one another.

Uterine Atony

Normally, after placental delivery, the uterine fundus is located at or just below the level of the umbilicus, and the uterus feels firm and globular. In cases of uterine atony, the fundus rises, the uterus feels soft and indistinct, and vaginal bleeding is profuse. When uterine massage and administration of uterotonic agents result in firming of the uterus and reduction or cessation of bleeding, uterine atony can be diagnosed.

Placental Factors

If heavy vaginal bleeding occurs after fetal delivery and the placenta has not been expelled, placental causes should be considered. Common issues include partial separation, entrapment, partial adhesion or accreta, and retained tissue.

Routine inspection of the placenta and membranes after delivery is essential to check for completeness. If torn blood vessels are observed on the fetal side of the placenta, the possibility of a retained accessory lobe should be considered. During manual removal, if the placenta cannot be separated from the uterine wall and traction on the umbilical cord results in inward retraction of the uterine wall with the placenta, placenta accreta is likely and manual removal should be stopped immediately.

Birth Canal Lacerations

Suspected lacerations require immediate and thorough examination of the cervix, vagina, and perineum.

Cervical Lacerations

These are more likely after delivery involving a large fetus, instrumental assistance, or breech extraction. Lacerations typically occur at the 3 o’clock and 9 o’clock positions and may extend into the lower uterine segment or vaginal fornix.

Vaginal Lacerations

The examiner should use the index and middle fingers to apply pressure to both sides of the episiotomy and inspect for tears and their severity, as well as for active bleeding. A tense, tender, fluctuant mass with skin discoloration suggests a vaginal hematoma.

Perineal Lacerations

These are classified into four degrees:

- First-degree: Tear of the perineal skin and vaginal mucosa with minimal bleeding.

- Second-degree: Involves fascia and muscle of the perineal body, possibly extending laterally and superiorly; bleeding may be significant.

- Third-degree: Extends to the anal sphincter, but the rectal mucosa remains intact.

- Fourth-degree: Complete disruption involving the rectum, anus, and vagina, exposing the rectal lumen. Despite extensive tissue damage, bleeding may be minimal.

Coagulation Disorders

These are most commonly secondary to excessive blood loss, though a small number of cases arise from primary disorders. Clinical features include continuous vaginal bleeding with non-coagulating blood, bleeding at multiple body sites, and skin ecchymosis. Diagnosis can be confirmed based on clinical presentation and laboratory tests such as platelet count, fibrinogen levels, and prothrombin time.

Management

Principles of Management

Treatment should target the underlying cause of bleeding, promptly control hemorrhage, restore blood volume, correct hypovolemic shock, and prevent infection.

General Management

While identifying the cause of postpartum hemorrhage, general supportive measures are essential. These include mobilizing medical personnel, cross-matching blood, establishing two intravenous lines to restore blood volume aggressively, ensuring airway patency with supplemental oxygen if necessary, monitoring vital signs and blood loss, inserting a urinary catheter to track urine output, and performing routine laboratory tests (e.g., complete blood count, coagulation profile) with ongoing monitoring.

Use of Tranexamic Acid

Tranexamic acid exerts an anti-fibrinolytic effect and is suitable for postpartum hemorrhage of various causes. It should be administered as early as possible, ideally within 3 hours postpartum. The recommended dose is 1 g by slow intravenous infusion over at least 10 minutes. If bleeding is not controlled after 30 minutes or recurs within 24 hours, a second dose may be given.

Management According to the Cause of Postpartum Hemorrhage

Uterine Atony

Enhancing uterine contraction is key to rapid hemostasis. After emptying the bladder via catheterization, the following approaches may be employed:

Uterine Massage or Compression

Abdominal Uterine Massage

After placental delivery, the practitioner massages and compresses the uterine fundus through the abdominal wall using rhythmic and firm hand movements—thumb in front and other fingers behind—helping expel intrauterine blood and promoting contraction.

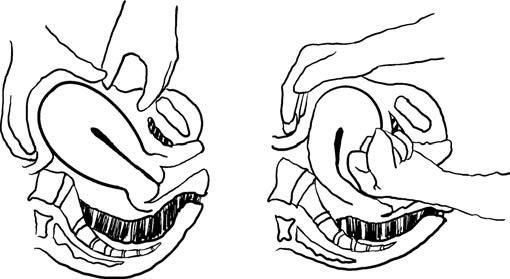

Bimanual Compression

One gloved hand is inserted into the vagina, with a fist pressing against the anterior uterine wall through the vaginal fornix. The other hand compresses the uterus from the abdomen, pressing the uterine body forward. Both hands work together to rhythmically compress and massage the uterus.

Effective massage should result in a clearly defined uterine contour, palpable firmness with ridges, and reduced bleeding from the vagina or uterine incision. Compression should be continued until normal uterine tone is restored and maintained, ideally in combination with uterotonic agents.

Figure 1 Abdominal uterine massage and bimanual abdominal-vaginal uterine massage

Administration of Uterotonic Agents

Oxytocin is the first-line medication for preventing and treating postpartum hemorrhage. Other agents may be selected based on the clinical scenario.

Oxytocin

This may be administered by continuous intravenous infusion (5–10 U/h) after dilution, or as 10 U via intramuscular, intramyometrial, or intracervical injection. The total dose should not exceed 60 U within 24 hours.

Carbetocin

A dose of 100 μg is administered via slow intravenous or intramuscular injection. Onset occurs within 2 minutes, with a half-life of 40–50 minutes.

Ergometrine

A dose of 0.2 mg is administered intramuscularly. It may be repeated every 2–4 hours if necessary, with a maximum of five doses. It is contraindicated in patients with hypertensive disorders of pregnancy or certain cardiovascular conditions.

Prostaglandins

This group includes carboprost tromethamine, misoprostol, and sulprostone. Intramuscular injection is generally the preferred route.

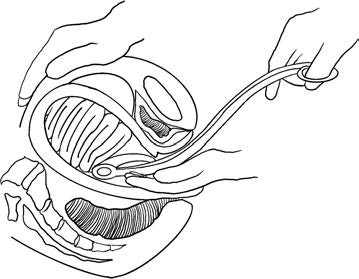

Intrauterine Tamponade

This involves packing the uterine cavity with gauze or using a balloon tamponade. Retained products of conception and uterine rupture must be excluded beforehand. Balloon tamponade is preferred after vaginal delivery, while either balloon or gauze may be used during cesarean section. Close monitoring of bleeding volume, uterine fundal height, and vital signs is necessary. Blood counts and coagulation profiles should be monitored. Tamponade materials are typically removed within 24 hours. Infection prophylaxis and concurrent use of uterotonic agents are advised.

Figure 2 Intrauterine gauze packing

Figure 3 Intrauterine balloon tamponade

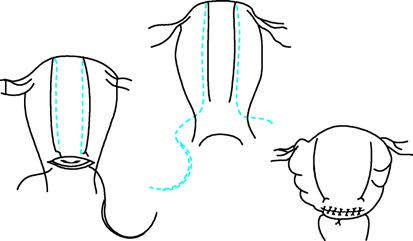

Uterine Compression Sutures

These are indicated when uterotonics and uterine massage are ineffective, especially in cases of uterine atony. The B-Lynch suture is commonly used. Other techniques include Hayman, Cho, and Pereira sutures. The choice depends on specific clinical needs.

Figure 4 Uterine compression suture technique

Pelvic Vessel Ligation

If the above measures fail, ligation of the ascending and descending branches of the uterine artery, or internal iliac artery ligation, may be considered.

Transcatheter Arterial Embolization (TAE)

This is an option in hospitals equipped with interventional radiology. It is appropriate for patients with stable vital signs who have not responded to conservative treatment. A catheter is inserted through the femoral artery into the internal iliac or uterine artery, where gelatin sponge particles are injected to embolize the artery. The embolic material is typically absorbed within 2–3 weeks, allowing vessel recanalization.

Hysterectomy

When active management fails and the patient’s life is at risk, subtotal or total hysterectomy should be performed without delay to save the patient’s life.

Placental Causes

If retained placenta is suspected after fetal delivery, immediate intrauterine examination is necessary.

If the placenta has already separated, it should be removed immediately.

If the placenta is adherent, gentle manual separation may be attempted.

If separation is difficult and placenta accreta is suspected, further attempts should cease. Management should be guided by the degree of bleeding and area of placental adherence, with either conservative approaches or hysterectomy considered.

Conservative Management

This is suitable for patients in stable condition without active bleeding, and when the area of placental invasion is small, uterine tone is good, and bleeding is minimal. Management may include partial resection, TAE, or medications such as mifepristone or methotrexate. During conservative management, color Doppler ultrasound should be used to monitor blood flow around the placenta. Vaginal bleeding should also be closely observed. If bleeding increases, curettage or hysterectomy may be required.

Hysterectomy

Hysterectomy is considered when active bleeding persists, the condition worsens, or in cases of placenta percreta. Complete placenta accreta may be associated with minimal or no active bleeding; in such cases, forceful manual removal of the placenta should be strictly avoided due to the risk of massive hemorrhage. Direct hysterectomy may be performed instead. Special attention is required in cases of a scarred uterus with coexisting placenta previa, especially when the placenta is attached at the site of the uterine scar. These cases are clinically challenging and may require timely referral to a facility equipped for advanced management.

Birth Canal Trauma

Complete hemostasis and repair of lacerations are necessary.

Superficial cervical tears without active bleeding do not require suturing.

Deep cervical tears with active bleeding should be sutured. The first suture should be placed at least 0.5 cm above the apex of the tear, usually using interrupted sutures.

If the laceration extends to the lower uterine segment, it may be repaired via an abdominal approach, with care taken to avoid injury to the bladder and ureters.

Vaginal and perineal lacerations should be repaired layer by layer according to anatomical planes, ensuring no dead space is left and avoiding penetration of the rectal mucosa.

In cases of soft tissue hematoma, the hematoma should be incised, blood evacuated, bleeding vessels ligated, and the wound sutured. A rubber drain may be placed if necessary.

Coagulopathy

Coagulation factors should be replenished promptly, and shock corrected. Commonly used blood products include fresh frozen plasma, cryoprecipitate, platelets, fibrinogen, prothrombin complex concentrate, and specific clotting factors. If disseminated intravascular coagulation (DIC) is present, treatment should follow DIC management protocols.

Hypovolemic Shock

Vital signs should be closely monitored. Measures include maintaining body temperature, administering oxygen, summoning assistance, and ensuring thorough documentation.

Blood volume should be rapidly and adequately replenished. Central venous pressure measurement can guide transfusion and fluid resuscitation in equipped hospitals.

Vasopressors and corticosteroids may be used temporarily in the presence of hypotension to support cardiac and renal function.

Arterial blood gas analysis should be performed as needed during resuscitation to correct acidosis in a timely manner.

Measures should be taken to prevent renal failure. If urine output falls below 25 ml/h, fluid replacement should be aggressive and urine output closely monitored.

Cardiac function should be protected. In cases of heart failure, cardiotonic agents and diuretics such as furosemide (20–40 mg intravenously) may be used. Repeat dosing may be considered after 4 hours if necessary.

Infection Prevention

Broad-spectrum antibiotics are typically administered to prevent infection.

Blood Transfusion Therapy for Postpartum Hemorrhage

Transfusion decisions should be based on clinical context to ensure timely and appropriate administration. Hemoglobin levels below 60 g/L usually require transfusion. When hemoglobin is below 70 g/L, transfusion may be considered. If ongoing bleeding is expected, transfusion thresholds may be adjusted accordingly.

Component therapy is commonly used:

- Packed Red Blood Cells

- Coagulation Factors, including fresh frozen plasma, cryoprecipitate, platelets, and fibrinogen.

Massive Transfusion Protocol (MTP)

A widely recommended regimen is to transfuse red blood cells, plasma, and platelets in a 1:1:1 ratio (e.g., 10 units of packed red cells + 1,000 ml of fresh frozen plasma + 1 unit of apheresis platelets).

With advances in laboratory and point-of-care testing, a Targeted Transfusion Protocol (TTP) may also be used. This involves individualized replacement of specific blood components based on the patient’s clinical condition and laboratory findings. In capable facilities, autologous blood salvage with filtration and reinfusion may also be utilized.

Prevention

Antenatal Prevention

Perinatal care should be strengthened. Anemia should be prevented and treated. General and emergency referral systems should be in place for patients identified as high-risk for postpartum hemorrhage.

Intrapartum Prevention

Labor progression should be closely monitored to prevent prolonged labor. Proper management of the second stage and active management of the third stage are crucial. The prophylactic use of uterotonic agents is the most important measure during the third stage of labor.

Postpartum Prevention

As most postpartum hemorrhage occurs within the first 2 hours after delivery, vital signs—including blood pressure, pulse, vaginal bleeding, uterine height, and bladder distention—should be closely monitored after placental delivery to allow early detection of bleeding and shock. Mothers should be encouraged to empty their bladders and engage in early skin-to-skin contact and breastfeeding, as this can reflexively stimulate uterine contractions and reduce bleeding.