Dystocia with the fetal head as the presenting part, also referred to as cephalic dystocia, is the most common type of fetal malposition.

Persistent Occiput Posterior Position and Occiput Transverse Position

When the fetal head engages in the maternal pelvis in the occiput posterior or occiput transverse position, internal rotation occurs as the biparietal diameter of the fetal head reaches the mid-pelvic plane. In most cases, the fetal head rotates anteriorly into an occiput anterior position, allowing the smallest diameter of the head to pass through the narrowest plane of the pelvis, facilitating natural vaginal delivery. However, in cases where after adequate trial labor the occiput fails to rotate anteriorly and remains positioned posteriorly or laterally in the maternal pelvis, this results in labor difficulties, a condition known as persistent occiput posterior position or persistent occiput transverse position. This condition accounts for approximately 5% of all deliveries.

Causes

Abnormal Pelvis and Poor Fetal Head Flexion

These are commonly seen in android pelvis types and anthropoid pelvises, which have a narrower anterior portion and a wider posterior portion of the inlet plane, allowing engagement in the occiput posterior or occiput transverse position.

Both types are frequently associated with mid-pelvic narrowing, which impedes internal rotation of the fetal head, increasing the chances of persistent occiput posterior or transverse positions.

A flat pelvis or a uniformly reduced pelvis facilitates engagement with the occiput transverse position, particularly when poor fetal head flexion and difficulties with internal rotation occur, resulting in the fetal head becoming arrested at the mid-pelvis and leading to a persistent occiput transverse position.

Other Abnormalities

Factors such as cervical myomas, cephalopelvic disproportion, placenta previa, uterine hypotonia, oversized or undersized fetuses, and fetal developmental abnormalities may all disrupt fetal head flexion and internal rotation, resulting in persistent occiput posterior or transverse positions.

Diagnosis

Clinical Manifestations

Engagement in the occiput posterior position leads to poor fetal head flexion and slow descent of the fetal head after the onset of labor, preventing effective cervical dilation. Reflexive stimulation of endogenous oxytocin release may cause uterine contractions to become uncoordinated, prolonging the second stage of labor.

In nulliparous women, labor duration increases by an average of 2 hours, while in multiparous women, the increase is around 1 hour.

Compression of the maternal rectum by the fetal occiput may cause a sensation of rectal pressure and a false urge to defecate before full cervical dilation. Premature bearing down may lead to excessive maternal exhaustion, cervical anterior lip edema, and slowed or arrested descent of the fetal head, further prolonging labor.

Abdominal Examination

Fetal limbs may be easily palpable along the maternal anterior abdominal wall, with the fetal back deviated toward the maternal posterior or lateral side. Fetal heart sounds are usually heard on the same side as the fetal limbs.

Vaginal and Rectal Examination

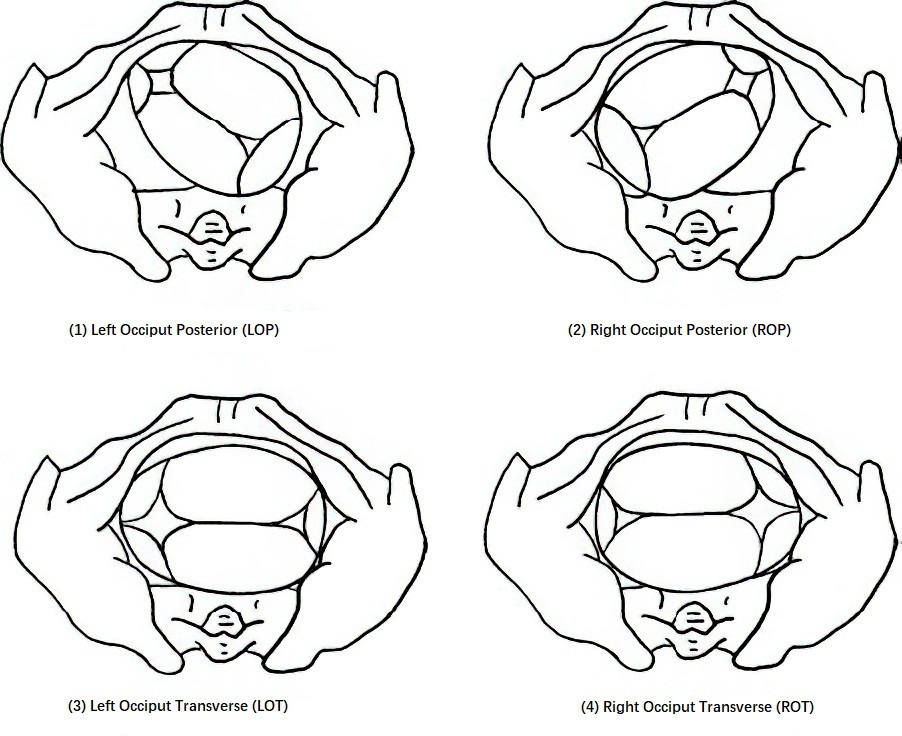

In occiput posterior positions, the posterior pelvis may feel empty. The sagittal suture of the fetal head aligns with the transverse diameter of the maternal pelvis.

If the posterior fontanelle is on the left side, it indicates the left occiput transverse position; if on the right, it indicates the right occiput transverse position.

If the sagittal suture lies along the left oblique diameter of the pelvis with the anterior fontanelle in the right anterior pelvis and the posterior fontanelle in the left posterior pelvis, it indicates the left occiput posterior position; the reverse indicates the right occiput posterior position.

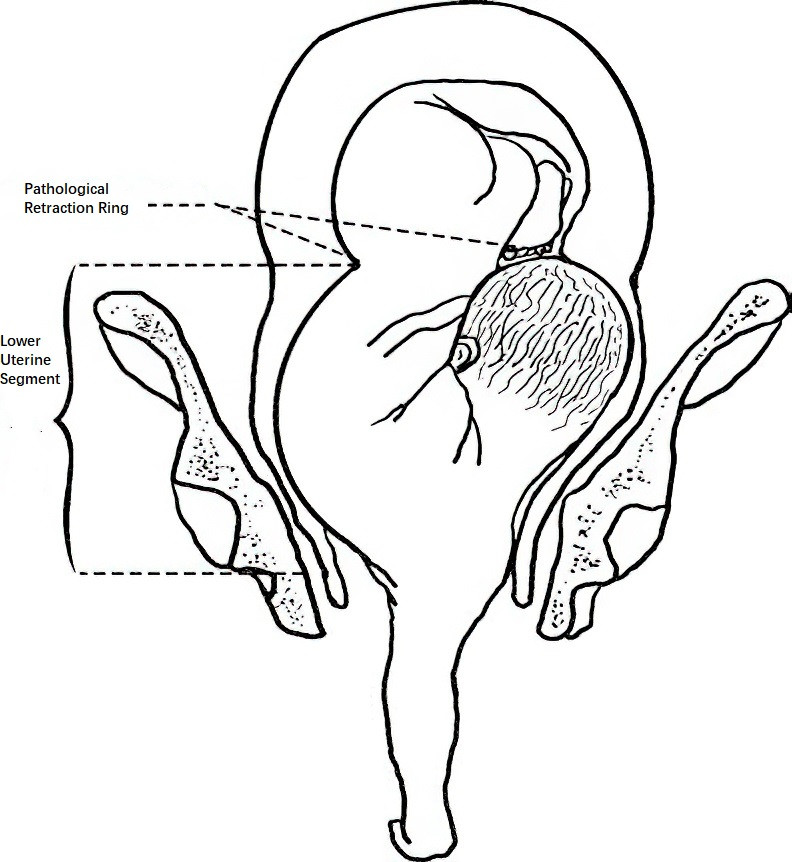

Figure 1 Persistent occiput posterior and occiput transverse positions

Poor flexion of the fetal head is suggested when the anterior fontanelle lies lower than the posterior fontanelle.

When complete cervical dilation occurs, the cephalic sutures and fontanelles may be difficult to palpate due to fetal head edema and overlapping cranial bones. In such cases, the position of the auricle and tragus can be used to determine fetal orientation.

Rectal examination can also be performed to assess the posterior pelvis and confirm fetal orientation. Sterile paper should cover the vaginal opening to prevent fecal contamination, and the examiner should insert a lubricated gloved index finger into the rectum for assessment.

Ultrasound Examination

Ultrasound can clearly identify the position of the fetal occiput and orbits to ascertain the fetal head orientation.

Mechanisms of Delivery

In the absence of cephalopelvic disproportion, the majority of occiput posterior and transverse positions can resolve with strong uterine contractions, allowing the occiput to rotate anteriorly by 90°–135° to become occiput anterior. If spontaneous rotation to the occiput anterior position does not occur during labor, the following delivery mechanisms may be encountered:

Occiput Posterior Position

During internal rotation, the left or right occiput posterior position may rotate posteriorly by 45° to become the direct occiput posterior position. This condition may lead to two outcomes:

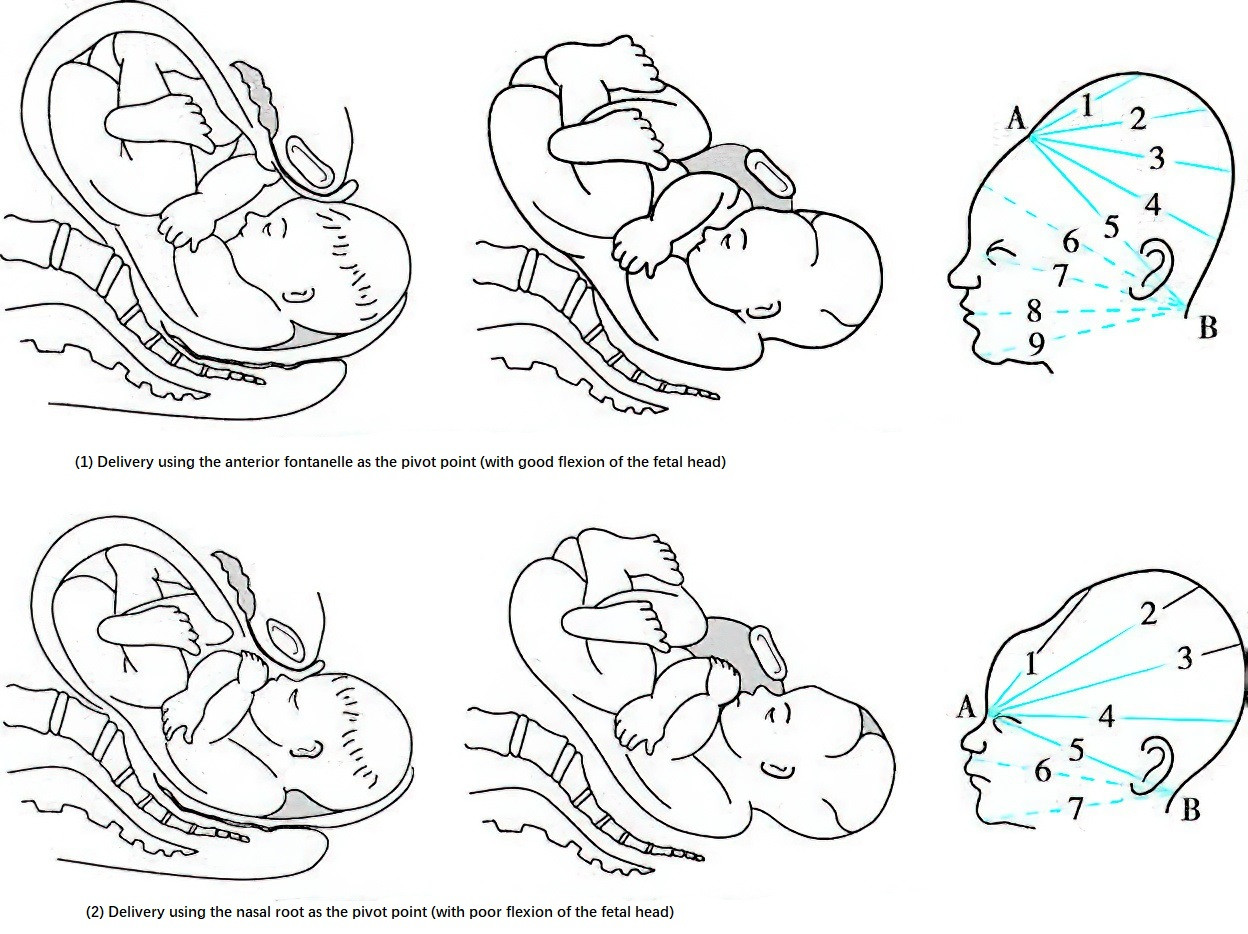

Good Flexion

The fetal head descends until the anterior fontanelle reaches the subpubic arch. The anterior fontanelle becomes the pivot point, allowing the head to flex further, delivering the vertex and occiput beyond the perineum. This is followed by extension of the fetal head to deliver the brow, nose, mouth, and chin sequentially under the subpubic arch. This is the most common mechanism of vaginal assisted delivery for occiput posterior positions.

Poor Flexion

The fetal head rotates with a larger occipitofrontal circumference, making delivery more challenging. Aside from rare instances of strong maternal forces and small fetuses achieving spontaneous delivery, operative assistance is typically required. The forehead may present first, and as the nasal root reaches the subpubic arch, it becomes the pivot point. The head then flexes to deliver the anterior fontanelle, vertex, and occiput, followed by extension to deliver the brow, nose, mouth, and chin sequentially.

Figure 2 Mechanism of delivery in occiput posterior position

Occiput Transverse Position

Delivery is generally possible through the vaginal route but often requires assistance, either manual or with vacuum extraction (or forceps), to rotate the head into the occiput anterior position for delivery. If internal rotation is obstructed or the occiput posterior position rotates forward by only 45°, yielding a persistent occiput transverse position, caution must be exercised.

Impact on Labor, Mother, and Fetus

Impact on Labor Progression

Persistent occiput posterior (or transverse) position often leads to delayed descent or even arrest of the fetal head during the second stage of labor. If not addressed in a timely manner, it can result in prolonged second-stage labor.

Impact on the Mother

This condition frequently causes secondary uterine hypotonia and subsequently prolongs labor. Prolonged fetal head compression on the soft birth canal may result in ischemia, necrosis, or tissue sloughing. Compression of adjacent organs, such as bladder paralysis, can lead to urinary retention and, in severe cases, genital tract injuries or fistula formation. Vaginal assisted deliveries become more common in these cases, increasing the risk of soft birth canal tears, postpartum hemorrhage, and puerperal infections.

Impact on the Fetus

Prolonged second-stage labor and the increased likelihood of operative delivery raise the risk of fetal distress and neonatal asphyxia, leading to a higher perinatal mortality rate.

Management

In cases of persistent occiput posterior or transverse position without pelvic abnormalities or a large fetus, trial labor may be allowed with close monitoring of labor progression, including uterine contraction strength, cervical dilation, fetal head descent, and any changes in fetal heart rate.

First Stage of Labor

Latent Phase

Adequate rest and nutrition for the mother are essential. Administration of pethidine is possible. In cases of uterine hypotonia, oxytocin may be used.

Active Phase

Mothers should avoid bearing down prematurely before full cervical dilation. After ruling out cephalopelvic disproportion, artificial rupture of membranes can be performed when the cervical dilation exceeds 3–5 cm, followed by a vaginal examination to assess pelvic size. Oxytocin infusion may be administered to augment uterine contractions, enabling vaginal delivery if conditions allow. If signs of fetal distress develop during trial labor or if artificial rupture of membranes and oxytocin infusion fail to produce effective progress, defined as cervical dilation increasing by less than 0.5 cm per hour or no progress at all, cesarean delivery should be performed to complete labor.

Second Stage of Labor

If labor progress in the second stage is slow—defined as nearing 2 hours in nulliparous women or 1 hour in multiparous women—a vaginal examination should be conducted to determine fetal position.

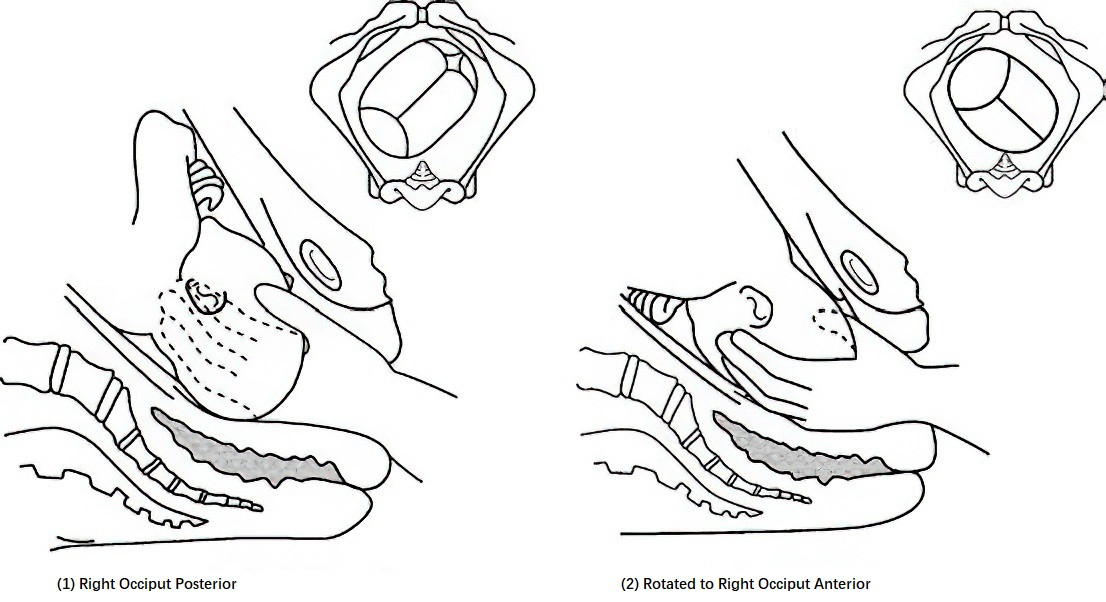

If the station is S+3 or lower (biparietal diameter at or below the ischial spines), manual rotation of the occiput to the anterior position can be attempted. Alternatively, vacuum extraction or forceps may be used to assist fetal head rotation into the occiput anterior position and facilitate vaginal delivery.

If manual rotation to the anterior position proves difficult, rotation to the direct occiput posterior position may be attempted to enable assisted delivery using forceps. If the fetus is delivered in the occiput posterior position, the poor flexion of the fetal head often results in delivery along the occipitofrontal diameter. To prevent perineal tears, a more extensive mediolateral episiotomy may be performed to assist delivery.

If labor in the second stage is prolonged and the fetal biparietal diameter remains above the ischial spines (above S+2) or if accompanied by fetal distress, cesarean delivery should be considered.

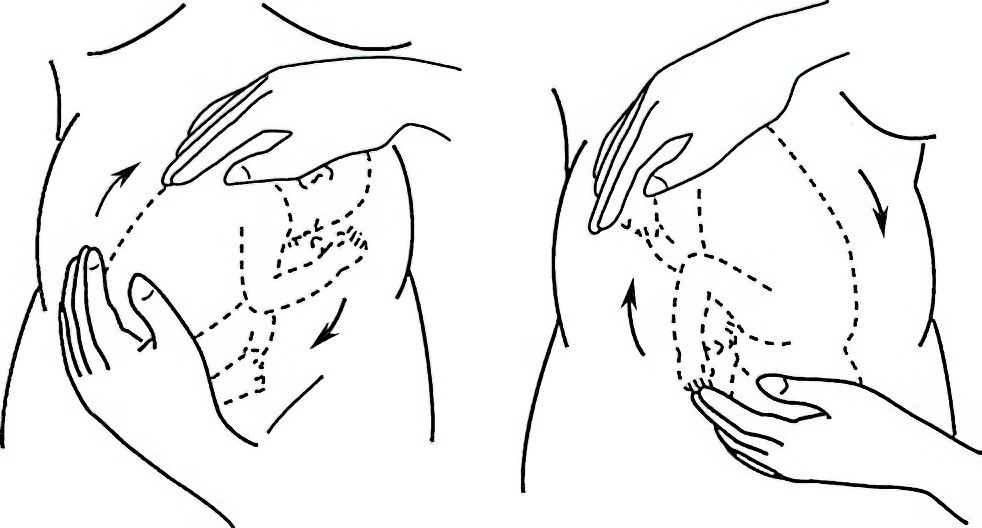

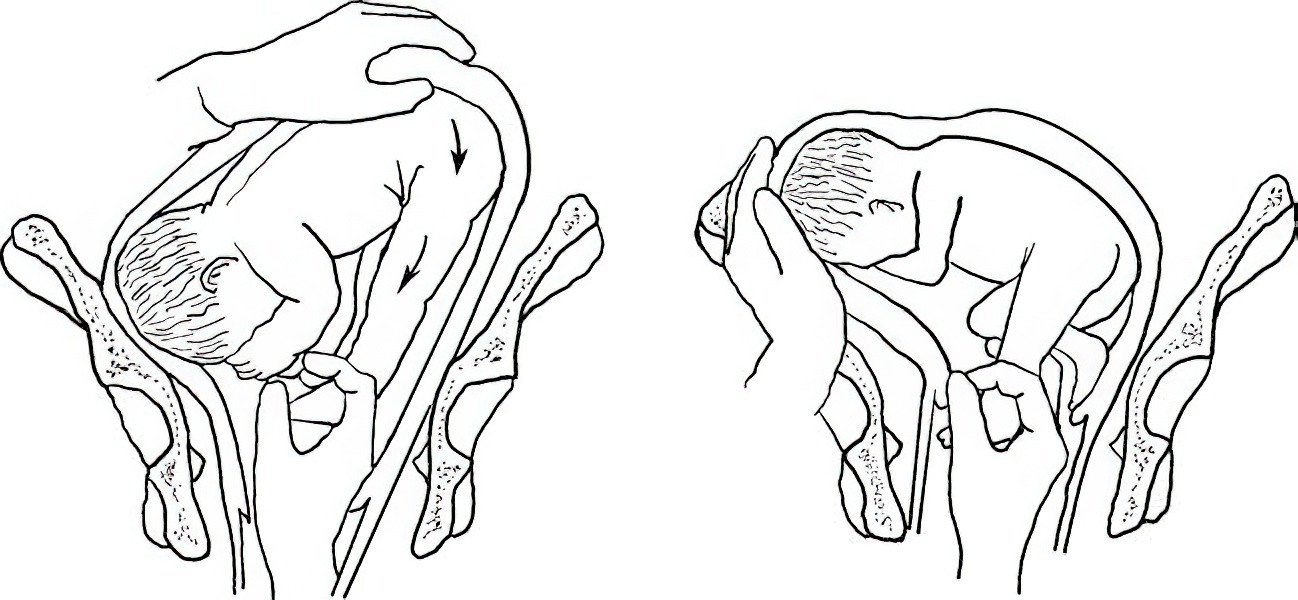

Figure 3 Manual internal rotation of the fetal head

Third Stage of Labor

Preparation for neonatal resuscitation is necessary. Given the increased risk of uterine hypotonia due to prolonged labor, uterotonic agents should be administered immediately after placental delivery to prevent postpartum hemorrhage. If soft birth canal lacerations are present, timely repair should be performed, along with administration of antibiotics to prevent infection.

Persistent Occipitoanterior and Occipitoposterior Positions of the Fetal Head (Sincipital Presentation)

When the fetal head engages in the pelvis in a neutral attitude, neither flexed nor extended, along the occipitofrontal diameter, and the sagittal suture aligns with the anteroposterior diameter of the pelvic inlet, this presentation is referred to as a persistent occipitoanterior or occipitoposterior position, collectively known as sincipital presentation. These include:

- Persistent occipitoanterior position: the occiput of the fetal head is oriented anteriorly toward the pubic symphysis; also referred to as the occipitopubic position.

- Persistent occipitoposterior position: the occiput is directed posteriorly toward the sacral promontory; also called the occipitosacral position.

These presentations account for approximately 1% of all deliveries. They pose significant risks to both mother and fetus and require appropriate management.

Diagnosis

Clinical Features

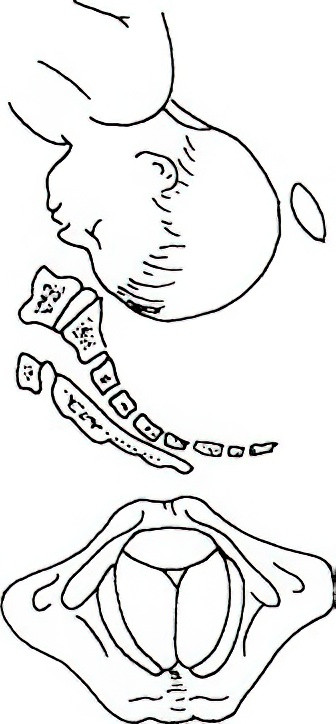

Due to the lack of flexion of the fetal head during labor, the presenting diameter entering the pelvic inlet becomes enlarged, which makes engagement difficult. Cervical dilation during the active phase may be delayed or arrested, and labor may become prolonged. In the occipitoposterior position, the head often fails to engage in the pelvic inlet, and even with full cervical dilation, the presenting part remains high, increasing the risk of labor obstruction, impending uterine rupture, or actual uterine rupture.

Abdominal Examination

In the occipitopubic position, the fetal back typically lies against the maternal abdominal wall, and fetal limbs are not easily palpable. Fetal heart tones are often heard high and close to the midline of the abdomen. In the occipitosacral position, the fetal limbs usually occupy the anterior abdominal wall, and the fetal chin may sometimes be palpated above the pubic symphysis.

Vaginal Examination

Due to the impaction of the fetal head at the pelvic inlet, full cervical dilation is difficult to achieve, often remaining at 3–5 cm. The sagittal suture lies in the anteroposterior diameter of the pelvic inlet, with a deviation of no more than 15°. In the occipitopubic position, the posterior fontanelle lies behind the pubic symphysis, and the anterior fontanelle lies in front of the sacrum. The reverse arrangement indicates an occipitosacral position.

Figure 4 Anterior high-positioned fetal head

Ultrasound Examination

In both persistent occipitoanterior and occipitoposterior positions, the biparietal diameter of the fetal head aligns with the transverse diameter of the pelvic inlet. In the occipitoposterior position, orbital reflections of the fetus may be detected above the pubic symphysis. In the occipitoanterior position, spinal reflections may be seen along the maternal abdominal midline.

Mechanism of Labor

In the occipitopubic position, the fetal head still has the potential to flex during labor. The inferior part of the fetal occiput may press against the posterior surface of the pubic symphysis as a pivot point. Initially, the anterior fontanelle slides past the sacral promontory, followed by the forehead descending along the sacrum into the pelvic inlet. As descent continues and extreme flexion of the head is corrected, the head may be delivered in an occipitoanterior position without the need for internal rotation or with minimal rotation of approximately 45°.

In contrast, in the occipitosacral position, the fetal spine aligns with the maternal spine, preventing the occipitofrontal diameter from passing through the relatively shorter anteroposterior diameter of the pelvic inlet. This inhibits flexion and descent of the fetal head, leading to a persistently high position. Even if engagement occurs, rotation of 180° to achieve an occipitoanterior position is difficult, making vaginal delivery highly unlikely.

Management

For the occipitopubic position, if there is no pelvic contraction, the fetus is of normal size, and uterine contractions are strong, a trial of vaginal delivery may be considered. Efforts should be made to enhance uterine contractions to aid head engagement and descent. If the trial fails or if there is obvious pelvic contraction, cesarean section should be performed. Once a diagnosis of occipitosacral position is confirmed, cesarean section is indicated.

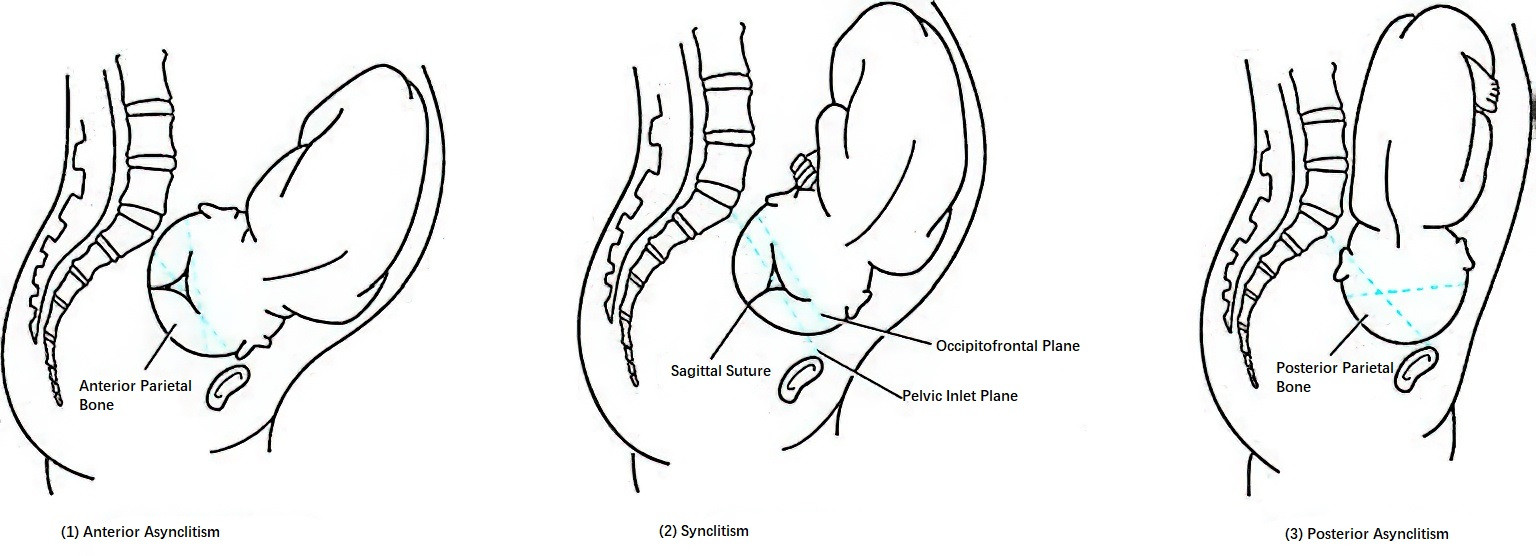

Anterior Asynclitism

When the fetal head in a transverse position enters the pelvis with lateral inclination, allowing the anterior parietal bone to descend first, the presentation is referred to as anterior asynclitism. The incidence is approximately 0.5%–0.8%. It is more likely to occur in cases of cephalopelvic disproportion, excessive pelvic inclination, or abdominal wall laxity.

Diagnosis

Clinical Features

Descent of the fetal head may be arrested due to difficulty of the posterior parietal bone in entering the pelvis after the anterior parietal bone descends first, leading to prolonged labor. If the anterior parietal bone compresses the bladder neck against the pubic symphysis, the mother may experience early signs of urinary difficulty or retention.

Abdominal Examination

The anterior parietal bone descends into the pelvis while the posterior parietal bone fails to engage. The fetal head folds against the fetal shoulders, and the head may not be palpable above the pubic symphysis, falsely suggesting engagement.

Vaginal and Rectal Examination

The sagittal suture aligns with the transverse diameter of the pelvic inlet but deviates posteriorly toward the sacral promontory. Most of the posterior parietal bone remains above the promontory, leaving the posterior pelvic cavity relatively empty. The anterior parietal bone is tightly impacted behind the pubic symphysis. The anterior cervical lip may become edematous due to compression, and the urethra may be compressed, making catheter insertion difficult. Rectal examination can help assess the posterior pelvis and assist in determining fetal position.

Mechanism of Labor

In anterior asynclitism, due to the flat and non-concave surface behind the pubic symphysis, the anterior parietal bone becomes firmly impacted behind it, preventing normal engagement of the fetal head. Cesarean section is therefore required.

Figure 5 Asynclitic engagement of the fetal head

Management

Efforts should be made to prevent engagement of the fetal head in anterior asynclitism prior to labor. In early labor, a seated or semi-recumbent position may help reduce pelvic inclination. Once anterior asynclitism is identified, cesarean section should be performed promptly, except in rare cases involving a small fetus, wide pelvis, and strong uterine contractions, where a brief trial of labor may be considered.

Face Presentation

Face presentation refers to the situation in which the fetal head presents in a state of extreme extension (occipitomental diameter), resulting in the occiput contacting the fetal back and the face becoming the presenting part. It is usually identified after the onset of labor. The incidence ranges from 0.8‰ to 2.7‰, and it is more common in multiparous women than in primiparas. The chin serves as the reference point for determining fetal position, which includes mentoanterior (left/right), mentoposterior (left/right), and mentotransverse (left/right) positions.

Diagnosis

Clinical Features

Engagement of the fetal head is often difficult, and the first stage of labor is frequently prolonged.

Abdominal Examination

In mentoanterior positions, the fetal trunk is extended, bringing the chest closer to the maternal anterior abdominal wall, and fetal heart sounds are more audible in the lower lateral abdomen. In mentoposterior positions, a markedly extended occiput can be palpated on the side of the fetal back. A noticeable groove may be felt between the occiput and back above the pubic symphysis. Fetal heart tones may be distant and faint.

Vaginal Examination

Palpation of the fetal mouth and chin confirms fetal position. The hard, round cranial bones are not palpable. After cervical dilation, only the soft and irregular features of the fetal face—such as the mouth, nose, eyes, zygomatic bones, and orbits—can be felt. When facial tissues such as the lips become edematous, they may be confused with the anus in breech presentation, potentially leading to misdiagnosis.

Ultrasound Examination

Ultrasound can differentiate between face and breech presentations based on the positions of the fetal orbits and occiput, and can confirm fetal position.

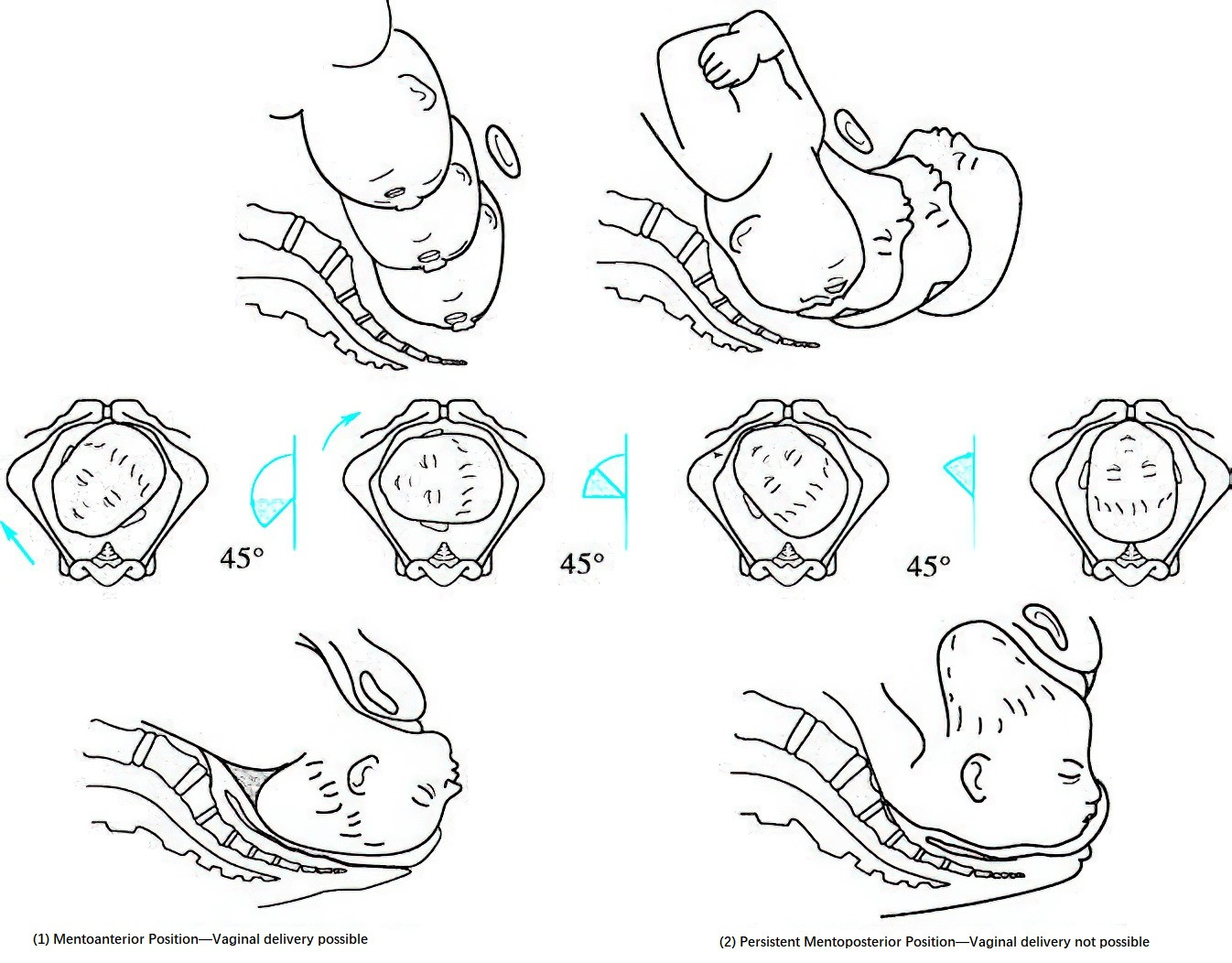

Mechanism of Labor

Face presentation rarely occurs at the pelvic inlet. It typically results from progression of brow presentation, where further extension of the fetal head during descent leads to face presentation.

Figure 6 Mechanism of labor in face presentation

Mentoanterior Position

In mentoanterior positions such as right mentoanterior, the occipitomental diameter aligns with the left oblique diameter of the pelvic inlet and descends to the mid-pelvis. The chin becomes the leading point and rotates 45° anteriorly to pass under the pubic arch. As the presenting part reaches the pelvic floor and the chin engages beneath the pubic arch, the fetal head undergoes gradual flexion, allowing sequential delivery of the mouth, nose, eyes, forehead, vertex, and occiput through the perineum. After restitution and external rotation, the shoulders and trunk are delivered.

Mentoposterior Position

After the fetal face reaches the pelvic floor, successful internal rotation of 135° can lead to delivery in a mentoanterior position. However, in some women, this rotation is restricted and the fetal neck remains hyperextended, resulting in persistent mentoposterior position. This cannot adapt to the pelvic curve, making vaginal delivery unfeasible and requiring cesarean section.

Mentotransverse Position

Most cases rotate 90° forward into a mentoanterior position and are delivered vaginally. Persistent mentotransverse positions cannot be delivered vaginally.

Management

Face presentation typically develops after labor has begun. In cases of prolonged or arrested labor, vaginal examination should be promptly conducted to confirm diagnosis. In mentoanterior positions, if uterine contractions are strong, there is no cephalopelvic disproportion, and fetal heart rate remains normal, a trial of labor may be allowed. In cases of secondary uterine inertia, artificial rupture of membranes and intravenous oxytocin infusion may be considered. If the second stage is prolonged, assisted delivery with forceps may be performed, usually requiring a generous episiotomy. For mentoanterior position with cephalopelvic disproportion, signs of fetal distress, or persistent mentoposterior position, cesarean section is indicated.

Breech Presentation

Breech presentation accounts for 3%–4% of all full-term deliveries and is the most common and easily diagnosed form of fetal malpresentation. In breech presentation, the sacrum is used as the reference point for determining fetal position, which includes six positions: left (or right) sacroanterior, left (or right) sacrotransverse, and left (or right) sacroposterior.

Etiology

Fetal Developmental Factors

The incidence of breech presentation is higher at earlier gestational ages. It is more common in late miscarriages and preterm births than in full-term births. Breech presentation typically converts to cephalic presentation between 28 and 32 weeks of gestation and then stabilizes. Regardless of gestational age, congenital anomalies such as anencephaly and hydrocephalus, or low birth weight, are associated with a significantly increased incidence of breech presentation.

Factors Affecting Fetal Movement Space

Excessive or restricted fetal movement can contribute to breech presentation. The condition is more frequent in multiple pregnancies than in singleton pregnancies. Abnormalities in amniotic fluid volume—polyhydramnios or oligohydramnios—can affect fetal mobility and increase the incidence of breech presentation. In multiparous women, excessive abdominal wall laxity, uterine anomalies (e.g., unicornuate or septate uterus), a short umbilical cord—especially when combined with fundal or cornual placental implantation or placenta previa—may lead to breech presentation. Additionally, pelvic tumors (e.g., lower uterine segment or cervical fibroids) or a contracted pelvis may obstruct the birth canal and result in breech presentation.

Classification

Breech presentation is categorized based on the position of the fetal lower limbs into mixed breech, frank breech, and footling presentation:

Mixed Breech Presentation (Complete Breech)

This is relatively common. Both hips and knees are flexed, and the presenting part includes the buttocks and both feet.

Frank Breech Presentation

This is the most common type. The hips are flexed while the knees are extended, with the fetal buttocks as the presenting part.

Footling Presentation (Incomplete Breech)

This is less common. The fetus presents with one or both feet, one or both knees, or a combination of one foot and one knee. Knee presentation is usually transient and often converts to footling presentation once labor begins.

Diagnosis

Clinical Features

In late pregnancy, women may experience discomfort in the upper abdomen during fetal movements. During labor, because the fetal buttocks and feet do not fit tightly against the lower uterine segment, cervix, and paracervical nerve plexus, cervical dilation is slower, labor is prolonged, and uterine inertia is more likely. Footling presentation is prone to premature rupture of membranes and umbilical cord prolapse.

Leopold’s Maneuvers

The fetal head, round and firm with a ballotable quality, is usually palpable in the uterine fundus. A broad and flat fetal back can be palpated on one side of the abdomen, and irregular small parts on the opposite side. If not engaged, soft, irregular buttocks may be felt above the pubic symphysis and are often mobile. Fetal heart sounds are usually heard loudest on the back side, just above the umbilicus. After engagement, fetal heart sounds are most prominent below the umbilicus.

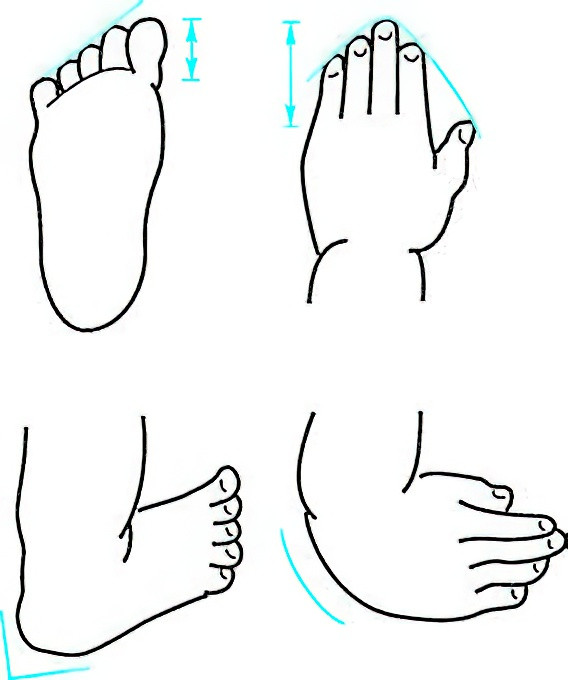

Vaginal Examination

Once the membranes rupture and the cervix dilates beyond 3 cm, the fetal buttocks can be palpated, including the anus, ischial tuberosities, and sacrum. The sacrum is key to confirming fetal position. In complete breech, the feet may also be felt, and identifying toes helps differentiate between left and right foot. Fetal toes are short and aligned, with a heel present, while fingers are longer and more irregularly spaced. As descent progresses, external genitalia may be palpated. In incomplete breech, when fetal lower limbs are felt, the possibility of cord prolapse should be assessed.

Figure 7 Differentiation between fetal hand and foot

Ultrasound Examination

Ultrasound helps determine the type of breech presentation and estimates fetal size.

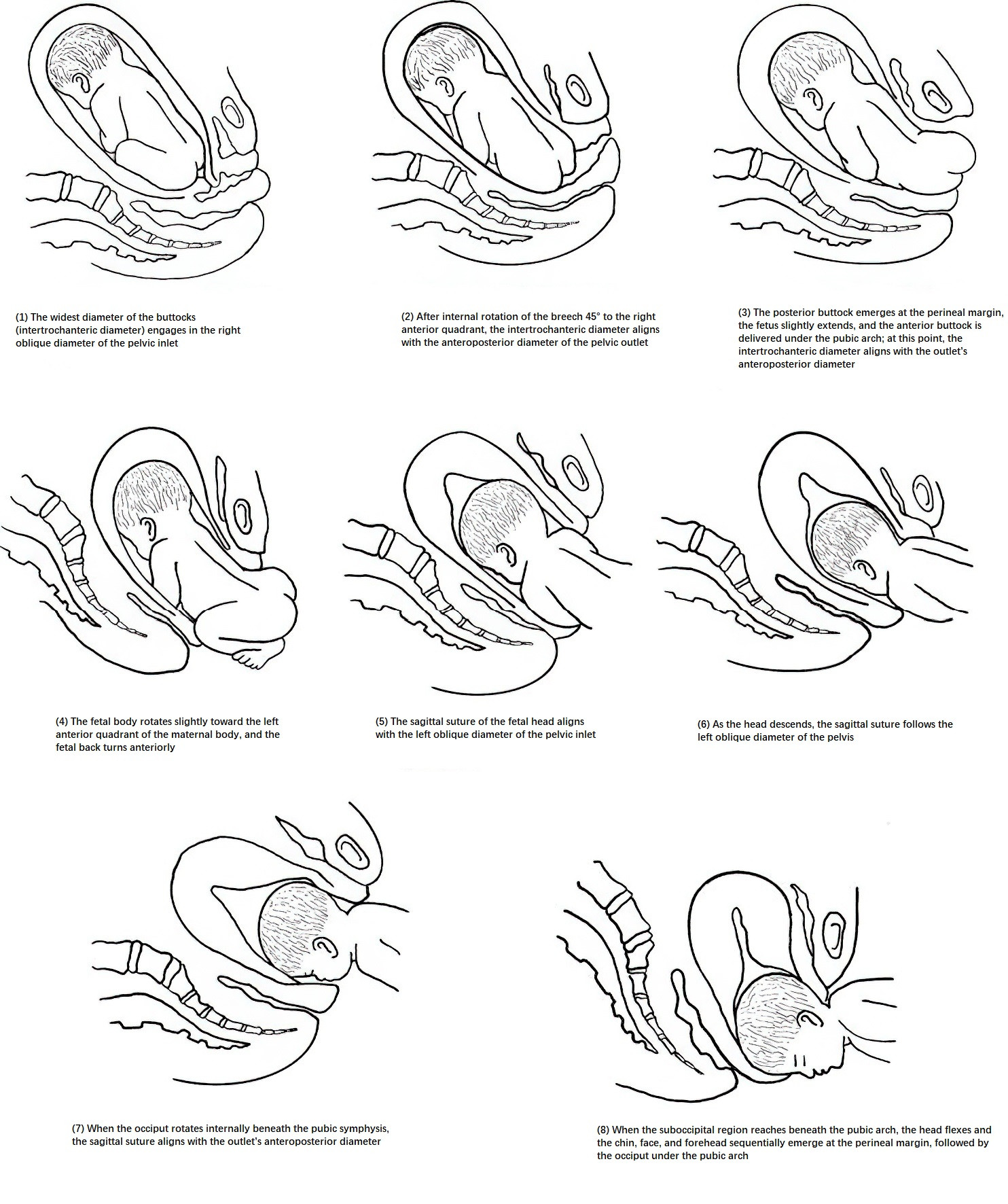

Mechanism of Labor

The relatively small and soft buttocks are delivered first, while the larger fetal head may encounter difficulty passing through the birth canal, often resulting in obstructed labor. The delivery mechanism is explained here using the example of right sacroanterior position:

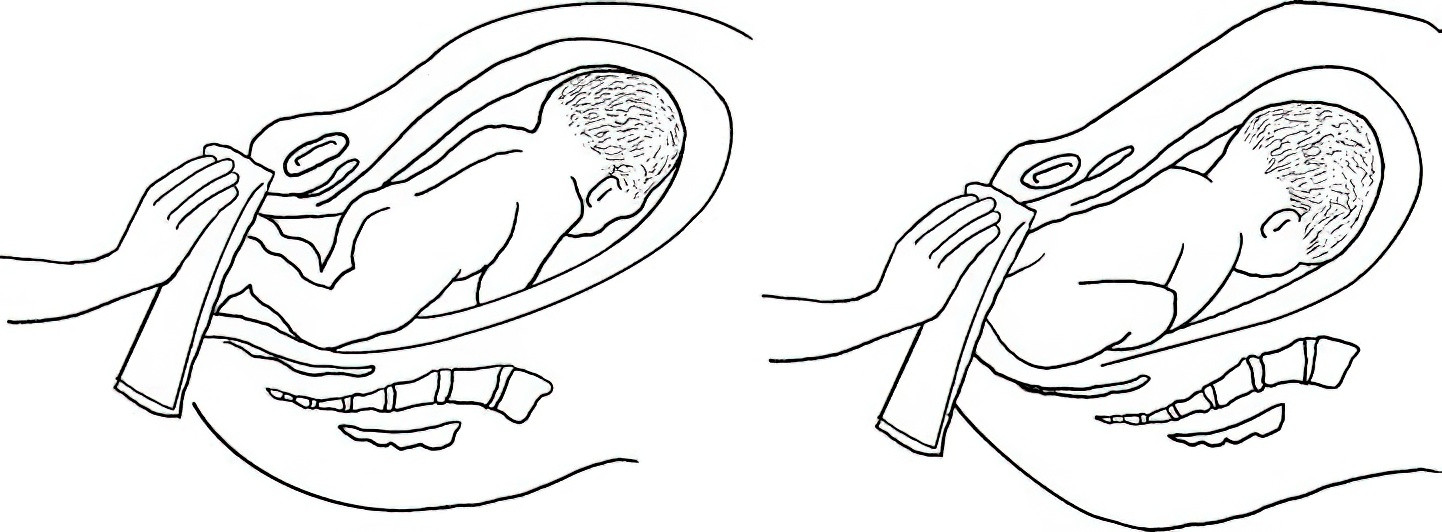

Figure 8 Mechanism of breech delivery

Delivery of the Buttocks

After labor begins, the widest part of the fetal buttocks (the bi-trochanteric diameter) engages in the right oblique diameter of the pelvic inlet. As descent continues, the anterior buttock reaches the pelvic floor first, then rotates 45° internally toward the maternal right anterior quadrant, bringing the anterior buttock under the pubic symphysis. The bi-trochanteric diameter then aligns with the anteroposterior diameter of the pelvic outlet. The posterior buttock is delivered first at the perineal margin as the fetal trunk undergoes lateral flexion, followed by the delivery of the anterior buttock beneath the pubic arch. The legs and feet follow.

Delivery of the Shoulders

After the buttocks are delivered, the fetal trunk rotates slightly to the maternal left anterior side. As the fetal back turns anteriorly, the biacromial diameter engages in the right oblique or transverse diameter of the pelvic inlet. When the shoulders reach the pelvic floor, the anterior shoulder rotates 45° toward the maternal right anterior quadrant, positioning it beneath the pubic arch. The shoulders then align with the anteroposterior diameter of the pelvic outlet. The posterior shoulder and arm are delivered first at the perineal margin, followed by the anterior shoulder and arm beneath the pubic arch.

Delivery of the Head

After the shoulders reach the perineum, the sagittal suture of the fetal head aligns with the left oblique or transverse diameter of the pelvic inlet. As the occiput reaches the pelvic floor, it rotates 45° to the maternal left anterior quadrant, bringing the occiput beneath the pubic symphysis. With the suboccipital region as the pivot point, the fetal head flexes, and the chin, face, and forehead are delivered sequentially over the perineum, followed by the occiput under the pubic arch.

Impact on Labor and Maternal-Fetal Outcomes

Impact on Labor

Because the buttocks have a smaller circumference than the head and do not fit snugly against the lower uterine segment and internal cervical os, cervical dilation may be delayed or arrested, prolonging the active phase of labor.

Impact on the Mother

The irregular shape of the buttocks and uneven pressure from the forewaters increase the risk of premature rupture of membranes, leading to a higher chance of puerperal infection. Breech presentations apply less pressure to the cervix and paracervical nerves than cephalic presentations, increasing the risk of secondary uterine inertia and postpartum hemorrhage. Both vaginal and cesarean breech deliveries contribute to a higher rate of operative interventions. Forceful traction before full cervical dilation may result in cervical lacerations or even lower uterine segment rupture.

Impact on the Fetus and Newborn

Premature rupture of membranes increases the risk of preterm birth. Umbilical cord prolapse is 10 times more common than in cephalic presentation. During delivery of the aftercoming head, molding is required for the head to pass through the pelvis. Compression of the cord between the head and cervix or pelvic wall may cause fetal hypoxemia and acidosis, potentially leading to neonatal asphyxia or death. The Apgar score at 1 minute is significantly lower in breech than cephalic deliveries. Additionally, delivery of the trunk may occur before full cervical dilation, and forced extraction of the head can cause direct trauma to the fetal head and cervical nerves and muscles, resulting in complications such as tentorial tears, spinal injury, intracranial hemorrhage, brachial plexus injury, sternocleidomastoid hematoma, or stillbirth.

Management

During Pregnancy

Before 36 weeks of gestation, most breech presentations convert spontaneously to cephalic presentation, and no intervention is generally required. If breech presentation persists beyond 36 weeks, corrective measures may be considered. Available options include:

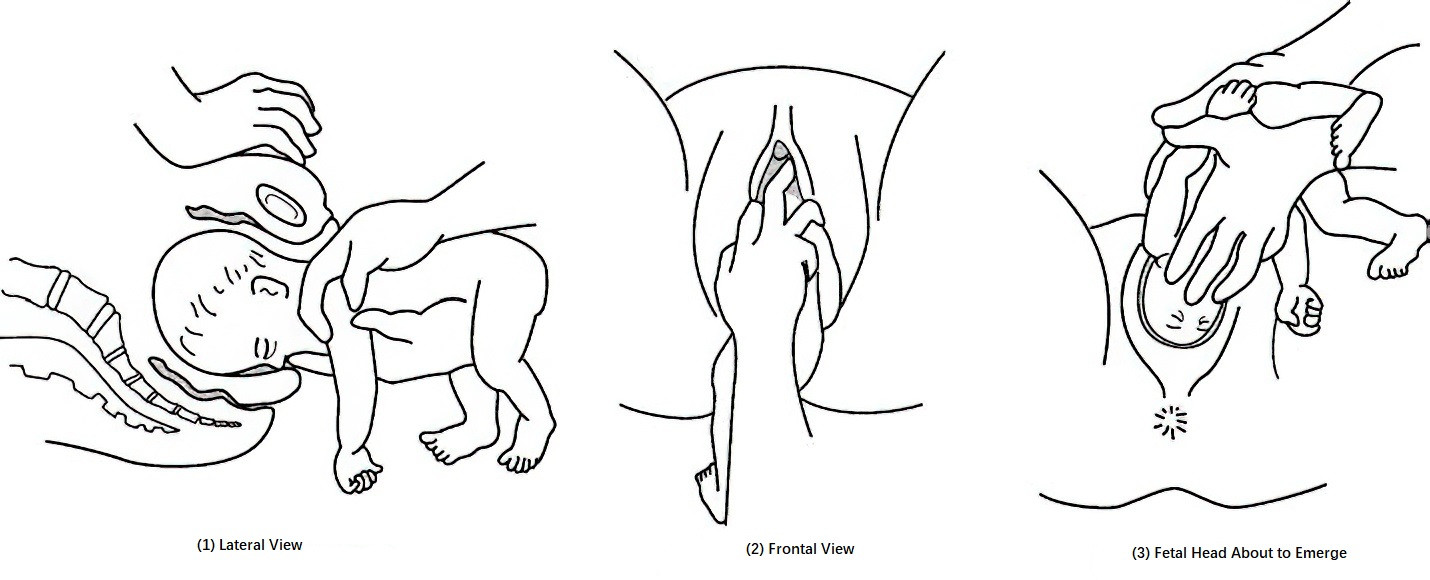

External Cephalic Version (ECV)

This involves manually applying pressure to the maternal abdomen to rotate the fetus forward or backward, converting a breech or transverse lie into a cephalic presentation. Although there are potential risks—such as placental abruption, fetal distress, premature rupture of membranes, and preterm birth—these are relatively rare. ECV is typically recommended after 36–37 weeks of gestation. It should only be performed in the absence of contraindications to vaginal delivery, with the administration of tocolytics beforehand, preparation for emergency cesarean delivery, and under ultrasound and electronic fetal monitoring.

Figure 9 External cephalic version for breech presentation

During Labor

Before labor begins, decisions about the mode of delivery should be made based on factors such as maternal age, current pregnancy course, parity, pelvic type, breech type, estimated fetal weight, fetal viability and development, and any complications. In clinical practice, most women opt for cesarean delivery.

Indications for Scheduled Cesarean Section

These include contracted pelvis, uterine scar, estimated fetal weight over 3,500 g, fetal growth restriction, fetal distress, extended fetal head position, history of obstructed labor, pregnancy complications, cord presentation, incomplete breech, and lack of provider experience with breech deliveries.

Vaginal Delivery

This should be managed by experienced obstetricians and midwives familiar with breech delivery techniques.

First Stage of Labor

Premature rupture of membranes should be avoided. The mother should rest in a lateral decubitus position and limit standing or walking. Adequate hydration and nutrition should be ensured. Enemas should be avoided, vaginal examinations should be minimized, and labor should not be induced with medication. Once membranes rupture, fetal heart tones should be monitored immediately. If abnormalities are detected, umbilical cord prolapse should be ruled out. In cases of prolapsed cord and incomplete cervical dilation, and if fetal heart tones are still reassuring, cesarean section should be performed promptly to rescue the fetus. If no cord prolapse is present, fetal heart rate and labor progression should be closely monitored. When fetal feet become visible at the vaginal opening during contractions, the cervix is often only dilated to 4–5 cm. This should not be mistaken for full dilation. During contractions, a sterile drape and the palm should be used to apply gentle pressure over the vaginal opening to prevent premature delivery of the buttocks and allow full cervical and vaginal dilation. During this process, fetal heart tones should be monitored every 10–15 minutes, and cervical dilation checked to prepare for delivery.

Figure 10 Blocking the breech to assist cervical dilation

Second Stage of Labor

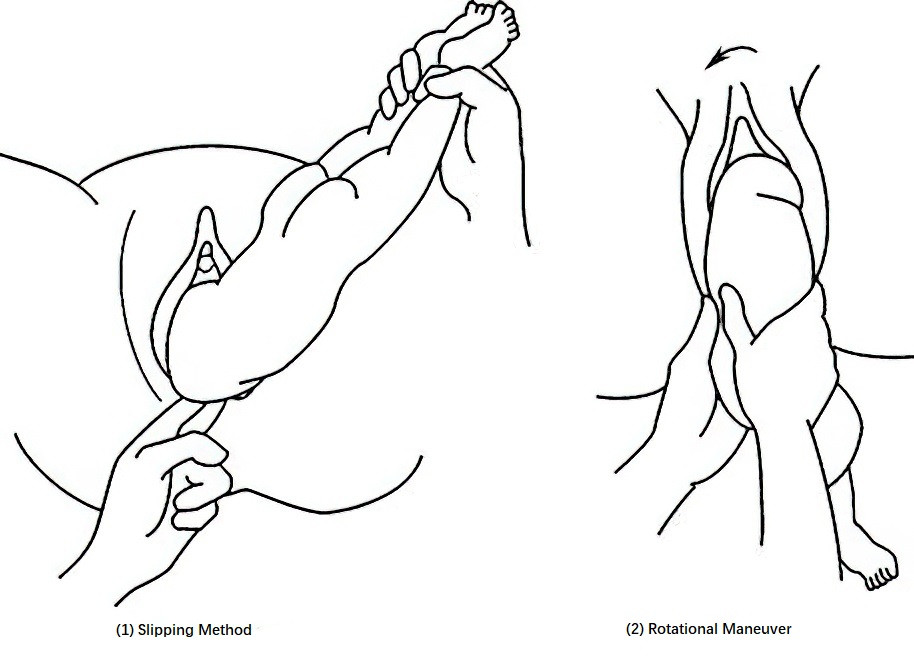

Preparations for delivery should include emptying the bladder. In primiparas, a mediolateral episiotomy should be performed. Three methods may be used:

Figure 11 Assisted delivery of the shoulders in breech presentation

Figure 12 Assisted delivery of the head in breech presentation

A. Assisted Breech Delivery

After spontaneous delivery of the breech to the umbilicus, the shoulders and head are assisted by the provider. For shoulder delivery, the sliding method may be used: the provider lifts both fetal legs with the right hand to flex the fetal trunk, exposing the posterior shoulder. The index and middle fingers of the left hand slide along the posterior shoulder and upper arm into the vagina to flex the elbow, guiding the fetal arm forward across the chest and out of the vagina. The posterior shoulder is delivered first, then the anterior shoulder emerges under the pubic arch as the trunk is gently extended downward. Alternatively, the rotating method may be used: the provider grasps the fetal buttocks with both hands and rotates the body counterclockwise while gently pulling downward to deliver the anterior shoulder under the pubic arch, followed by clockwise rotation to deliver the posterior shoulder.

After full delivery of the shoulders and upper limbs, the fetal back is rotated anteriorly, and the fetus is placed astride the provider's left forearm. The provider’s left index and ring fingers support the fetal maxilla on both sides (avoiding the supraclavicular fossa), while the right middle finger presses the occiput to assist with flexion. The fetal chin, mouth, nose, eyes, and forehead are sequentially delivered using the occiput as a pivot point. If descent of the fetal head is difficult, forceps may be applied to the aftercoming head. This reduces the risk of clavicle fracture, cervical dislocation, and sternocleidomastoid hematoma from excessive manual traction. The forceps must be applied over the occipitomental diameter, and the fetal head fully flexed prior to delivery.

B. Breech Extraction

The entire fetus is delivered by traction. This method is rarely used due to a higher risk of fetal injury.

C. Spontaneous Breech Delivery

This is rare, and usually seen in multiparas with small fetuses, strong uterine contractions, and a wide birth canal.

After the umbilicus is delivered, the entire delivery should be completed within 8 minutes to avoid fetal death from cord compression. The fetal head should not be pulled forcefully to prevent excessive traction on the neck, which may cause brachial plexus injury or severe cranial deformation leading to tentorial or cerebellar dural tears and intracranial hemorrhage.

Third Stage of Labor:

Secondary uterine inertia may prolong labor and lead to postpartum hemorrhage. Intramuscular oxytocin or prostaglandins should be administered to prevent bleeding, and active resuscitation should be provided for neonatal asphyxia. The soft birth canal should be routinely examined, and any injuries promptly repaired. Antibiotics should be given to prevent infection.

Shoulder Presentation

When the presenting part of the fetus is the shoulder, it is referred to as shoulder presentation, which is considered the most unfavorable fetal position for both mother and fetus. In this situation, the fetal body lies transversely above the pelvic inlet, with its longitudinal axis perpendicular to that of the mother. Shoulder presentation accounts for approximately 0.25% of all full-term deliveries. Using the scapula as the reference point, there are four fetal positions: left anterior, left posterior, right anterior, and right posterior scapular positions. Except in cases of fetal demise or preterm delivery where the fetus may be compressible, vaginal delivery of a full-term living fetus is not feasible. Without timely management, uterine rupture may occur, posing serious risks to maternal and fetal life.

Etiology

The causes are similar to those of breech presentation but are not entirely the same. Common factors include:

- Excessively lax abdominal walls in multiparous women, such as pendulous abdomen causing the uterus to tilt forward and the fetal axis to deviate from the birth canal, resulting in an oblique or transverse lie.

- Preterm fetus that has not yet turned to a cephalic presentation.

- Placenta previa.

- Uterine malformations or tumors.

- Polyhydramnios.

- Pelvic stenosis.

Diagnosis

Abdominal Examination

The uterus appears transversely elliptical, with fundal height lower than expected for gestational age. Neither the fetal head nor breech can be palpated at the fundus or above the pubic symphysis, which appears empty. The uterine transverse diameter is wider than in normal pregnancies. One side may reveal the fetal head, and the other the breech. In anterior shoulder positions, the fetal back is aligned with the maternal abdominal wall and feels flat; in posterior positions, irregular limbs may be palpable. Fetal heart tones are best heard on both sides of the umbilicus.

Vaginal Examination

This is conducted when membranes have ruptured and the cervix is significantly dilated. In labor with a transverse lie, membranes are often already ruptured, and palpation may reveal the scapula, acromion, ribs, or axilla. The axillary apex points toward the fetal head and shoulder, helping determine if the head is on the left or right side of the maternal pelvis. If the scapula faces posteriorly, the presentation is posterior; otherwise, it is anterior. If the fetal hand prolapses into the vagina, the "handshake method" can help determine whether it is the left or right hand—the examiner can only shake hands with the fetus using the same side of their own hand. According to the “anterior-opposite, posterior-same” rule: for left anterior shoulder presentation, a prolapsed right hand would match the examiner’s right hand; for left posterior shoulder presentation, a prolapsed left hand would match the examiner’s left hand.

Ultrasound Examination

Ultrasound can confirm shoulder presentation by identifying the fetal head, spine, and heart, and can also determine the specific fetal position.

Impact on Labor and Maternal-Fetal Outcomes

Impact on Labor

With shoulder presentation, the fetal body becomes impacted above the pelvic inlet, and the cervix is unable to fully dilate. If a second twin presents in a transverse lie after the first is delivered and no measures are taken, the presenting part may become arrested, prolonging the second stage of labor.

Impact on the Mother

Shoulder presentation prevents effective cervical dilation and increases the risk of uterine inertia. Uneven pressure on the forewaters may lead to premature rupture of membranes. After rupture, the uterine cavity shrinks, increasing the chance of fetal entrapment or folding. As labor progresses, the fetal shoulder and part of the thorax may be forced into the pelvic inlet. The fetal neck may become further flexed laterally, folding the head toward the fetal abdomen and causing impaction in one iliac fossa, while the breech becomes lodged in the opposite iliac fossa or folds into the upper uterine cavity. The presenting arm may prolapse into the vagina, forming a neglected (impacted) shoulder presentation—the most dangerous form for the mother—obstructing labor and causing arrest. Continued contractions may lead to a pathological contraction ring, a sign of impending uterine rupture. In cases of impacted shoulder presentation, full-term fetuses, whether alive or deceased, cannot be delivered vaginally, increasing the risk of cesarean section, intraoperative hemorrhage, and infection.

Figure 13 Impacted shoulder presentation and pathological retraction ring

Impact on the Fetus

Ineffective engagement of the presenting part and uneven pressure on the forewaters may cause premature rupture of membranes, cord prolapse, and prolapse of the upper limb, significantly increasing the risk of fetal distress or death. For full-term living fetuses, surgical delivery is necessary. Delayed management in impacted shoulder presentation increases delivery difficulty and risk of trauma.

Management

During Pregnancy

Regular prenatal checkups can help detect and correct shoulder presentation early. Management is similar to that for breech presentation. External cephalic version may be attempted. If unsuccessful, the patient should be hospitalized in advance for monitoring and delivery planning.

During Labor

Delivery decisions should be based on fetal size, parity, fetal viability, degree of cervical dilation, membrane status, and presence of complications.

Live Fetus

In primiparous women, cesarean section is indicated regardless of cervical dilation or membrane status. In multiparous women, cesarean section is also preferred. If the cervix is dilated more than 5 cm, membranes have ruptured, amniotic fluid is not completely lost, and the fetus is not large, internal version under general or epidural anesthesia may be attempted to convert to breech presentation for delivery. In twin pregnancies, if the second fetus turns to a shoulder presentation after delivery of the first due to sudden uterine cavity shrinkage and fetal repositioning, internal version should be performed immediately to convert to breech or cephalic presentation.

Figure 14 Internal version maneuver

Signs of Impending or Actual Uterine Rupture

Regardless of fetal viability, cesarean section is required to save the mother’s life. In cases of large uterine rupture or infection, hysterectomy may be necessary.

Intrauterine Fetal Demise without Signs of Impending Uterine Rupture

If the cervix is fully dilated, destructive procedures under general anesthesia may be considered. Postoperative examination of the lower uterine segment, cervix, and vaginal canal should be performed to check for lacerations. Any injuries should be repaired promptly, and measures should be taken to prevent postpartum hemorrhage and puerperal infection.

Compound Presentation

When the fetal head or breech presents together with an extremity (upper or lower limb) entering the pelvic inlet simultaneously, it is referred to as compound presentation. The incidence is approximately 0.08% to 0.1%. It most commonly occurs in preterm labor, with the combination of the fetal head and one hand or forearm being the most frequent presentation.

Etiology

Compound presentation typically occurs when the presenting part is not well engaged in the pelvic inlet, leaving space that allows an extremity to slip into the pelvis. Common contributing factors include a high-floating fetal head, pelvic stenosis, malpresentation, premature rupture of membranes, preterm birth, polyhydramnios, lax abdominal walls in multiparous women, and multiple gestation.

Diagnosis

Labor tends to progress slowly, and compound presentation is often identified during vaginal examination. The most common type involves the fetal head and hand. It is important to distinguish this condition from shoulder and breech presentations.

Management

When compound presentation is diagnosed, cephalopelvic disproportion should first be ruled out. If no cephalopelvic disproportion is present, the woman may be positioned in lateral recumbency on the side opposite the prolapsed limb, which often leads to spontaneous retraction of the limb. If both presenting parts have already entered the pelvis, and the cervix is nearly or fully dilated, the limb may be gently repositioned upward, and downward pressure can be applied to the uterine fundus to assist fetal head descent and facilitate vaginal delivery. If repositioning is unsuccessful and the compound presentation obstructs fetal descent, cesarean section is considered appropriate. If the breech and hand present together, it usually does not interfere with delivery and does not require special intervention. In cases of clear cephalopelvic disproportion or signs of fetal distress, early cesarean section is recommended.