Abnormalities of the birth canal encompass both bony pelvis and soft tissue abnormalities, with bony pelvis abnormalities being more common. These abnormalities can obstruct the passage of the fetus during delivery. Obstetric evaluations are required during labor to assess the size and shape of the pelvis, determine the type and severity of the contracted pelvis, and comprehensively consider factors such as uterine contractions and fetal characteristics to decide the method of delivery.

Abnormalities of the Bony Pelvis

When the dimensions or shape of the bony pelvis are abnormal, resulting in a pelvic cavity smaller than the dimensions necessary for the presenting part of the fetus to pass through, the condition is referred to as a contracted pelvis. The contraction may involve a single shortened dimension or multiple dimensions simultaneously, and it can affect a single plane or multiple planes. When one dimension is shortened, it is necessary to assess the lengths of other dimensions within the same plane and to comprehensively analyze the overall size and shape of the pelvic cavity for accurate diagnosis.

Classification

Contracted Pelvic Inlet

Contracted pelvic inlet is characterized by reduced anteroposterior diameter at the plane of the pelvic inlet, typically associated with flat pelvis types. The diagonal conjugate is the primary measurement, classified into three grades. The flat pelvis generally includes the following two types:

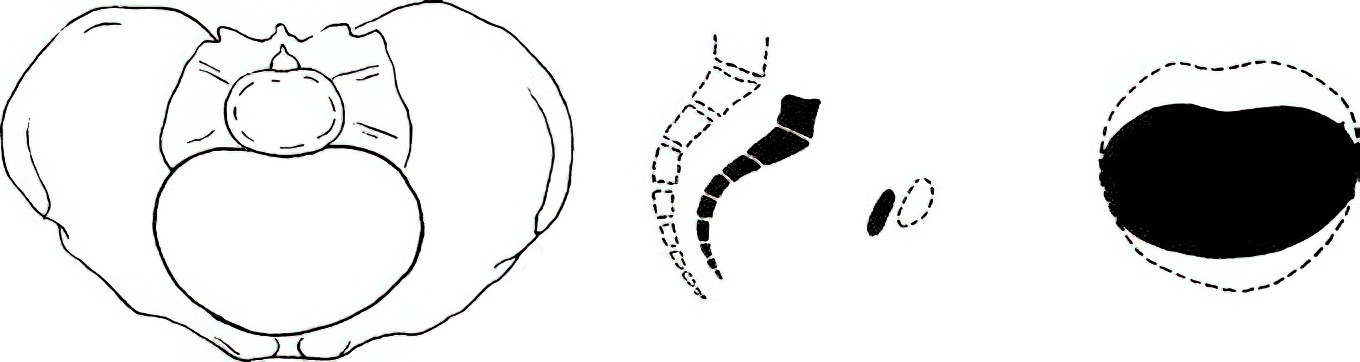

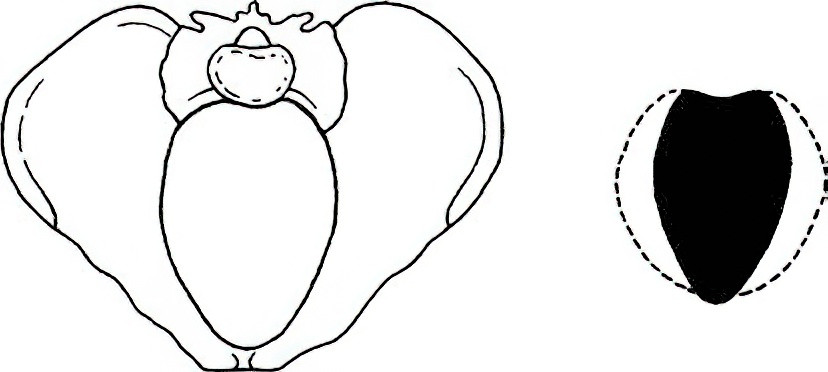

- Simple Flat Pelvis: The pelvic inlet has a transversely oval shape. The sacral promontory protrudes forward and downward, shortening the anteroposterior diameter while leaving the transverse diameter normal.

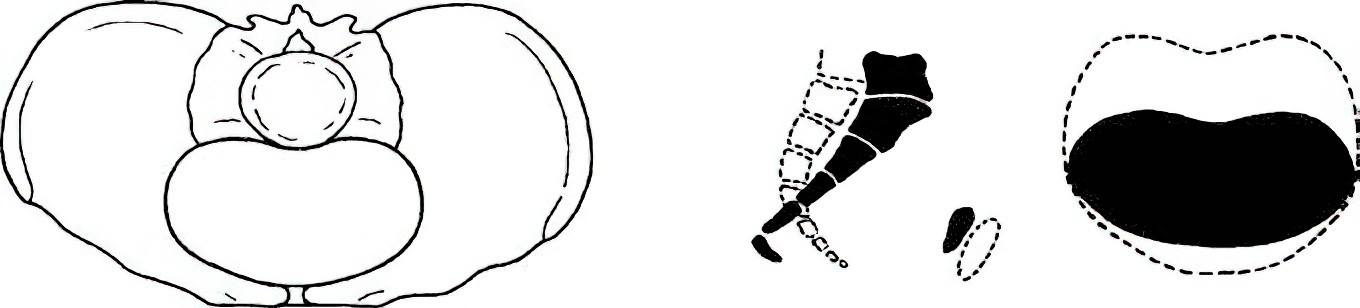

- Rachitic Flat Pelvis: The pelvic inlet has a transversely kidney-shaped appearance. The sacral promontory prominently protrudes forward, further shortening the anteroposterior diameter of the inlet. The sacrum straightens and tilts posteriorly, while the coccyx bends forward towards the outlet plane. The width of the transverse pelvic outlet increases due to outward flaring of the ischial tuberosities and a wider pubic arch angle.

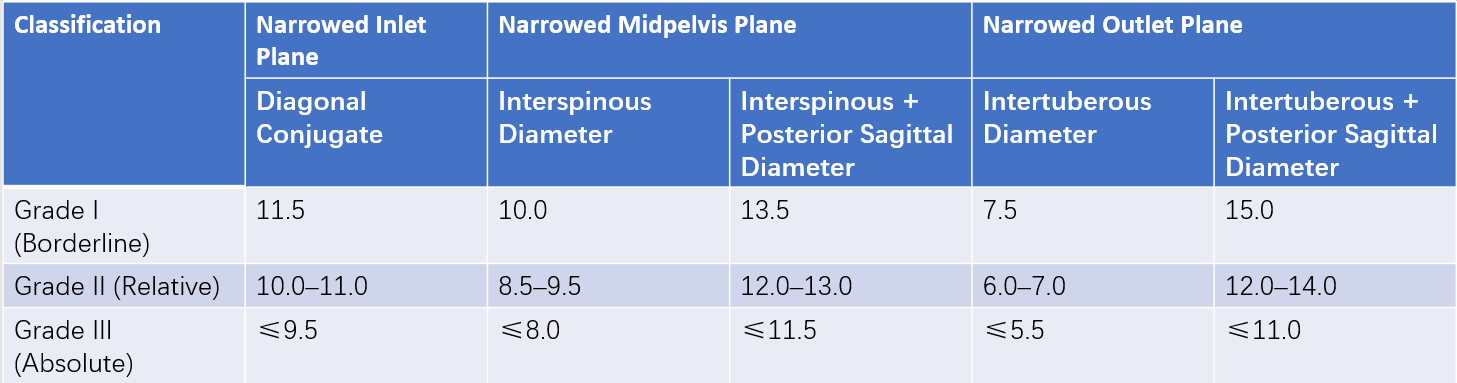

Table 1 Classification of narrowing in the three pelvic planes (unit: cm)

Figure 1 Simple flat pelvis

Figure 2 Rachitic flat pelvis

Contracted Midpelvis

Contraction of the midpelvis plane is more common than contraction of the pelvic inlet. It is typically seen in anthropoid or android pelvis types, and key measurements include the interspinous diameter and the posterior sagittal diameter of the midpelvis. This condition is classified into three grades.

Contracted Pelvic Outlet

Contracted pelvic outlet often accompanies midpelvis contraction and is typically observed in android pelvis types. Key measurements include the intertuberous diameter and the posterior sagittal diameter of the pelvic outlet, which are classified into three grades.

The following two types are commonly observed in cases of midpelvis and pelvic outlet contractions:

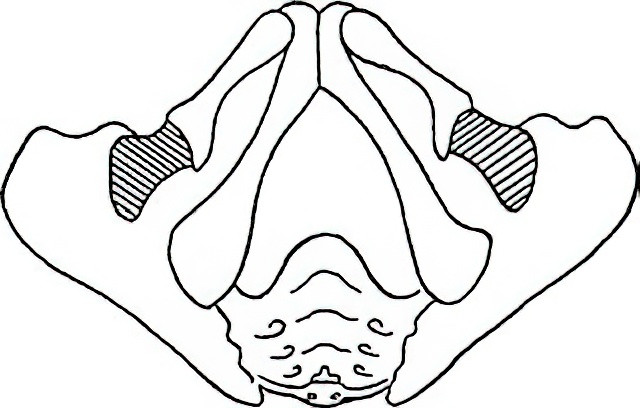

- Funnel-Shaped Pelvis: In this type, the dimensions of the pelvic inlet are normal, but the lateral pelvic walls converge inward, resembling a funnel shape. The midpelvis and pelvic outlet planes are significantly narrowed, shortening the interspinous and intertuberous diameters. The width of the greater sciatic notch (as measured by the sacrospinous ligament width) is less than two transverse fingers. The pubic arch angle is less than 90°, and the combined value of the intertuberous diameter and the posterior sagittal diameter of the outlet is less than 15 cm. This pelvis type is commonly associated with android pelvis.

- Transversely Contracted Pelvis: This type resembles the anthropoid pelvis and is characterized by shortened transverse diameters across all planes of the pelvis. The pelvic inlet plane has a vertically oval shape. The transverse contraction of the midpelvis and outlet planes frequently leads to dystocia.

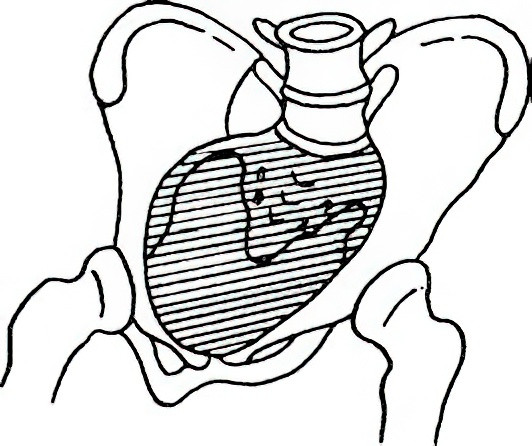

Figure 3 Funnel-shaped pelvis

Figure 4 Pelvis with reduced transverse diameter

Contraction of All Three Pelvic Planes

When the overall shape of the pelvis remains typical of the normal gynecoid pelvis, but all three pelvic planes exhibit contraction with each diameter being 2 cm or more below normal values, the pelvis is referred to as a generally contracted pelvis. This type is more frequently seen in women of short stature with proportionally balanced body shapes.

Deformed and Pathological Pelvis

This category includes pelvises that have lost their normal shape and symmetry due to various deformities, including pelvic asymmetry associated with conditions such as limping or scoliosis, and pelvic fractures leading to structural abnormalities. An asymmetrical pelvis is characterized by a significant difference (>1 cm) between the two lateral oblique diameters (measured from one posterior superior iliac spine to the contralateral anterior superior iliac spine) or between the two lateral straight diameters (measured from the same posterior superior iliac spine to the corresponding anterior superior iliac spine). Pelvic fractures may result in sacrococcygeal fusion or anteriorly displaced fractured coccyx, shortening the anteroposterior diameter of the pelvic outlet and causing pelvic outlet narrowing, which can adversely affect delivery.

Figure 5 Oblique pelvis

Clinical Manifestations

Contracted Pelvic Inlet Plane

Abnormal Fetal Presentation and Position

Pregnant individuals with contracted pelvises exhibit an incidence of abnormal fetal positions, such as breech, shoulder, or face presentation, more than three times higher than those with normal pelvises. Cases of cephalic presentation often display cephalopelvic disproportion (CPD). Nulliparous women may present with a pointed abdomen, while multiparous women may develop a pendulous abdomen. During labor, fetal descent into the pelvis may be delayed, and a positive “fetal head overlapping at the symphysis” sign is observed. In rare cases, when the pelvic inlet is shallow and flat, the fetal head may give the false impression of molding at the vaginal opening, despite not engaging. If the sacrum and symphysis are palpable above the superior edge of the pubic symphysis, it can indicate a misdiagnosis of low fetal head positioning.

Contracted pelvic inlets are classified into the following:

- Grade I (Critical Narrowing): Most cases permit vaginal delivery.

- Grade II (Relative Narrowing): A significantly increased difficulty with vaginal delivery is observed. Vaginal delivery may be attempted in cases of smaller fetuses and adequate uterine contractions, depending on the outcomes of trial labor.

- Grade III (Absolute Narrowing): Cesarean section is required.

Abnormal Progression of Labor

The degree of pelvic narrowing, fetal position, fetal size, and strength of uterine contractions affect labor progression differently. With relative CPD caused by a narrowed pelvic inlet, labor may be prolonged during the latent phase and the early active phase. In cases where the fetal head eventually engages after adequate trial labor, rapid progression may occur during the late active phase. However, with absolute CPD, fetal engagement cannot occur, even with normal uterine contractions, fetal size, and position, often resulting in uterine inertia, labor arrest, or obstructed labor.

Other Complications

An increased incidence of premature rupture of membranes (PROM) and umbilical cord prolapse is observed. Rarely, patients with contracted pelvic inlets may experience complications such as overactive uterine contractions and obstructed labor, leading to symptoms like abdominal pain, tenderness, difficulty urinating, and urinary retention. Clinical examinations may reveal lower abdominal tenderness, pubic symphysis separation, cervical edema, pathological retraction rings, visible hematuria, or even signs of uterine rupture. Delays in intervention can increase the likelihood of uterine rupture.

Contracted Midpelvis Plane

Abnormal Fetal Position

After the fetal head engages and progresses to the midpelvis plane, rotational movement may be obstructed by transverse narrowing of the midpelvis. This results in persistent occipitoposterior or transverse positions as the biparietal diameter becomes stuck at the narrowed midpelvis, preventing vaginal delivery.

Abnormal Progression of Labor

Internal rotation of the fetal head typically occurs during near-complete cervical dilation. Persistent occipitoposterior or transverse positions often lead to secondary uterine inertia, causing an extended or stalled second stage of labor.

Other Complications

A fetal head obstructed at the midpelvis plane may become deformed due to forced labor or interventions aimed at correcting fetal position. Significant soft tissue swelling, pronounced caput succedaneum, and in severe cases, intracranial hemorrhage, scalp hematomas, or fetal distress may occur. Assisted vaginal delivery in such cases often leads to severe perineal and vaginal trauma or neonatal birth injuries. In cases of severe midpelvis contraction combined with strong uterine contractions, signs of impending uterine rupture or even uterine rupture itself may occur.

Contracted Pelvic Outlet Plane

Contracted pelvic outlet often coexists with midpelvis contraction. It frequently results in secondary uterine inertia and stalling of the second stage of labor, as the biparietal diameter fails to pass through the narrowed pelvic outlet. Forced vaginal delivery is not advisable, as it risks severe soft tissue trauma in the birth canal and neonatal birth injuries.

Diagnosis

During labor, the pelvis is an unchanging structural factor and is a key component in evaluating the ease or difficulty of delivery. Pelvic abnormalities, cephalopelvic disproportion (CPD), and other potential issues need to be assessed during pregnancy to facilitate early diagnosis and determine the appropriate delivery method.

Medical History

A thorough inquiry into the patient’s medical history is necessary. This includes investigating past conditions such as rickets, tuberculosis of the spine or hip joint, poliomyelitis, or bone trauma. For multiparous individuals, a detailed delivery history is needed to ascertain whether there was any history of difficult labor, assisted vaginal delivery, or neonatal birth trauma.

General Examination

Observations should focus on whether the body structure or gait shows abnormalities. Individuals shorter than 145 cm should be considered at risk for a generally contracted pelvis. Assessments include checking for spinal or hip joint deformities and examining the symmetry of the Michaelis rhomboid (a diamond-shaped area on the lower back).

- Spinal scoliosis or limping may suggest asymmetrical pelvis.

- A stocky skeletal structure and a short neck may indicate a funnel-shaped pelvis.

- If the Michaelis rhomboid is symmetrical but overly flattened, it may suggest a flat pelvis; if too narrowed, it may indicate midpelvic contraction.

- Symmetrically prominent and narrowed posterior superior iliac spines may suggest features of an anthropoid pelvis; if asymmetrical, with one posterior superior iliac spine more pronounced, it may indicate an asymmetrical pelvis.

Abdominal Examination

Observations include the shape of the abdomen. Pointed abdominal shapes in nulliparous individuals may suggest contracted pelvic inlet. Measurements of fundal height and abdominal girth, along with Leopold’s maneuvers, can help evaluate the fetal presentation, position, and whether the presenting part is engaged. Ultrasound imaging may assist in confirming these findings. During labor, dynamic monitoring of fetal station and potential signs such as a positive “fetal head above pubis” sign are necessary for further evaluation.

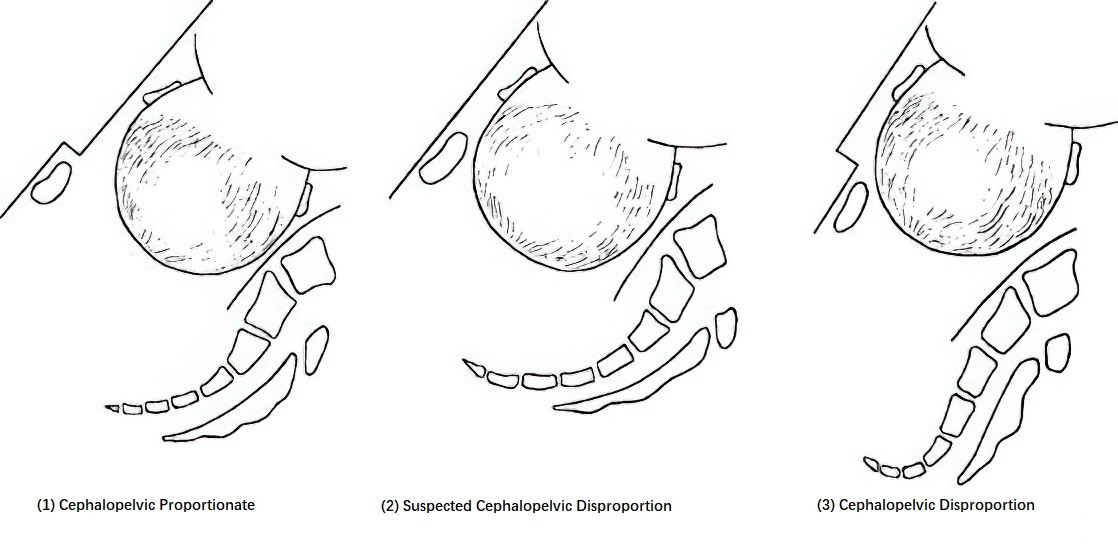

Examination Procedure

After advising the patient to empty the bladder and lie supine with legs extended, the examiner places one hand above the symphysis pubis and uses the other hand to push the fetal head toward the pelvic cavity.

- Negative Sign: The fetal head is below the level of the symphysis pubis, indicating engagement.

- Suspicious Positive Sign: The fetal head is at the same level as the symphysis pubis, suggesting potential CPD.

- Positive Sign: The fetal head is above the level of the symphysis pubis, indicating CPD.

A positive “fetal head above pubis” sign alone is insufficient to make a clinical diagnosis. CPD generally indicates the possibility of relative or absolute pelvic narrowing. Assessing CPD also depends on pelvic tilt and fetal position; therefore, final diagnosis can only be confirmed by observing labor progression or through trial of labor.

Figure 6 Assessing cephalopelvic disproportion

Pelvic Measurement

Pelvic size is primarily assessed through obstetric examinations. Measurements include the diagonal conjugate, anteroposterior diameters of the midpelvis and pelvic outlet, posterior sagittal diameter of the outlet, intertuberous diameter, and pubic arch angle. Additional evaluations involve assessing sacral promontory prominence, the width of the greater sciatic notch, degree of ischial spine protrusion, curvature of the sacral hollow, and sacrococcygeal joint mobility.

- A reduction in pelvic dimensions of 2 cm or more below normal values indicates a generally contracted pelvis.

- A diagonal conjugate less than 11.5 cm along with a prominent sacral promontory suggests a contracted pelvic inlet, characteristic of flat pelvis.

- The width of the greater sciatic notch indirectly reflects the length of the midpelvis posterior sagittal diameter.

Midpelvis and pelvic outlet contraction often coexist. Evaluations include intertuberous diameter, posterior sagittal diameter of the outlet, pubic arch angle, ischial spine protrusion, and width of the greater sciatic notch to indirectly determine the degree of midpelvic contraction.

- Intertuberous diameter < 8 cm.

- Combined intertuberous diameter and posterior sagittal diameter < 15 cm.

- Pubic arch angle < 90°.

- Greater sciatic notch width < two transverse fingers, indicating midpelvis and pelvic outlet contraction, associated with a funnel-shaped pelvis.

Dynamic Monitoring of Fetal Position and Labor Progression

Situations potentially indicative of a contracted pelvis include the following:

- In nulliparous individuals, a lack of fetal head engagement or abnormal presentations (e.g., breech, shoulder presentation) after labor onset.

- Cephalic presentations with asynclitism or obstructed fetal head rotation.

- Slow labor progression despite normal uterine contractions and fetal positioning.

These cases necessitate timely evaluation to determine the degree of CPD and whether vaginal trial labor is feasible.

Effects on Labor and Maternal-Fetal Health

Effects on Labor Progression

A contracted pelvis can cause labor to be prolonged or arrested.

A contracted pelvic inlet hinders engagement of the presenting part, increasing the risk of abnormal fetal presentations.

A contracted midpelvis slows fetal descent and can lead to prolonged active phase and second stage of labor.

A contracted pelvic outlet impedes fetal descent, prolonging the second stage of labor.

Effects on Maternal Health

A contracted pelvic inlet affects engagement, heightening the risk of abnormal fetal presentations.

A contracted midpelvis hinders internal fetal rotation, often resulting in persistent occipitoposterior or occipitotransverse positions.

Obstruction of fetal descent increases the likelihood of secondary uterine inertia, prolonged or arrested labor, and necessitated operative delivery.

Prolonged compression of the birth canal can lead to severe complications such as vesicovaginal or rectovaginal fistulas.

Severe obstructed labor accompanied by strong uterine contractions may result in pathological retraction rings, signs of impending uterine rupture, or actual rupture.

The risk of postpartum infection increases due to frequent vaginal exams, assisted delivery, premature rupture of membranes, and prolonged labor.

Effects on Fetal and Neonatal Health

A contracted pelvic inlet increases risks of a high-floating fetal head, PROM, cord presentation, and cord prolapse.

Prolonged labor raises the likelihood of fetal hypoxia or ischemia due to prolonged compression in the birth canal.

Efforts to force the fetus through the narrowed birth canal or assisted deliveries elevate the risk of neonatal intracranial hemorrhage, birth trauma, infections, and other complications.

Management of Labor

Absolute pelvic contraction has become rare, while borderline or relatively contracted pelvises are more commonly encountered in clinical practice. Management of labor requires determining the type and degree of pelvic contraction, assessing uterine contraction strength (labor force), fetal position, fetal size, fetal heart rate, degree of cervical dilation, fetal descent, and membrane status. A comprehensive analysis, incorporating factors such as obstetric history, parity, and maternal age, is used to determine the appropriate mode of delivery.

Management of Contracted Pelvic Inlet Plane

Absolute Pelvic Inlet Contraction

A diagonal conjugate measurement of ≤9.5 cm indicates the need for cesarean delivery.

Relative Pelvic Inlet Contraction

A diagonal conjugate of 10.0–11.0 cm, combined with an appropriately sized fetus, normal uterine contractions, normal fetal position, and reassuring fetal heart rate, suggests that trial of labor under close monitoring may be considered. The primary criteria for evaluating the adequacy of trial labor are the degree of cervical dilation and uterine contraction intensity. Trial labor in cases of pelvic inlet contraction may proceed once the cervix is dilated to 4 cm or more. For cases with unruptured membranes, artificial rupture of membranes may be performed when the cervical dilation exceeds 3–5 cm. If, following membrane rupture, uterine contractions are strong and labor progresses smoothly, vaginal delivery is often achievable. In cases of uterine inertia during trial labor, oxytocin infusion may be administered to enhance contractions. If the fetal head persists above the pelvic inlet without descent, cervical dilation is arrested, or signs of fetal distress emerge, cesarean delivery should be performed promptly to conclude labor.

Management of Contracted Midpelvis Plane

Midpelvis contraction primarily leads to difficulties with fetal head flexion and internal rotation, frequently resulting in persistent occipitotransverse or occipitoposterior positions. Clinical manifestations commonly include prolonged or arrested labor during the active phase or second stage, accompanied by secondary uterine inertia. If the cervix is fully dilated and the fetal biparietal diameter has descended to or below the ischial spine level, manual rotation of the fetal head to an occipitoanterior position may be attempted to facilitate spontaneous delivery. Alternatively, forceps-assisted delivery or vacuum extraction may be performed. If the biparietal diameter has not descended to the ischial spine level, or signs of fetal distress are present, cesarean delivery is necessary to complete labor.

Management of Contracted Pelvic Outlet Plane

Trial labor in cases of pelvic outlet contraction should be approached with caution. Clinicians often estimate pelvic outlet size based on the combined measurement of the intertuberous diameter and the posterior sagittal outlet diameter.

- When the combined measurement exceeds 15 cm, vaginal delivery is typically feasible, though forceps-assisted delivery or vacuum extraction may occasionally be required.

- When the combined measurement is ≤15 cm, it is difficult for a full-term fetus to pass through the vaginal canal, and cesarean delivery is indicated.

Management of Generally Contracted Pelvis

If the fetus is estimated to be small, uterine contractions are adequate, the fetal position is normal, and cephalopelvic proportion is favorable, trial labor may be pursued. If the fetus is large and cephalopelvic disproportion is evident, cesarean delivery is recommended.

Management of Abnormal Pelvis

Management depends on the type and degree of pelvic deformity, as well as fetal size and uterine contraction strength. Severe pelvic deformities with obvious cephalopelvic disproportion necessitate cesarean delivery.

Abnormalities of the Soft Birth Canal

The soft birth canal consists of the vagina, cervix, lower uterine segment, and pelvic floor soft tissues. Abnormalities in the soft birth canal can also result in abnormal labor. These abnormalities may arise from congenital developmental defects or acquired pathological conditions.

Vaginal Abnormalities

Transverse Vaginal Septum

Transverse vaginal septa are often located in the upper or middle portions of the vagina. These septa usually have a small opening, centrally or slightly off-center, which can be mistaken for the external cervical os. During labor, careful examination allows for diagnosis.

Transverse vaginal septa can obstruct the descent of the presenting part. When the septum becomes thin due to stretching, an X-shaped incision can be made at the opening under direct visualization. Remaining portions of the septum may be excised after delivery and the residual edges sutured using absorbable sutures, either intermittently or continuously.

If the septum is thick and high, significantly blocking the descent of the presenting part, cesarean delivery is required.

Longitudinal Vaginal Septum

In cases where a longitudinal vaginal septum is accompanied by a duplicated uterus and double cervix, the fetus from one uterine cavity generally descends through the corresponding vaginal canal, while the septum is pushed to the opposite side. Labor often proceeds without difficulty.

If a longitudinal vaginal septum is present with a single cervix and the septum is located anterior to the presenting part, it may spontaneously rupture if it is thin, allowing for normal labor. However, if the septum is thick and obstructs the descent of the presenting part, a midline incision may be made in the septum. Any residual septum can be excised, and the edges sutured after delivery with absorbable sutures.

Vaginal Masses

Vaginal masses may include vaginal cysts, tumors, or extensive condyloma acuminata.

If a vaginal cyst is large enough to obstruct the descent of the presenting part, puncturing and aspirating the cyst contents may temporarily resolve the issue, with definitive management undertaken postpartum.

If a tumor in the vagina prevents the descent of the presenting part and cannot be removed vaginally, cesarean delivery is required, and the tumor can be addressed after delivery.

Large or extensive condyloma acuminata may obstruct the birth canal, and vaginal delivery could result in severe vaginal tears. A cesarean delivery is recommended in such cases.

Cervical Abnormalities

Cervical Adhesions and Scarring

Cervical adhesions and scarring may result from dilatation and curettage, infections, surgical procedures, or physical treatments. These can cause cervical dystocia.

Mild membranous adhesions may respond to separation, mechanical dilation, or radial cervical incisions. Severe cervical adhesions or scarring often necessitate cesarean delivery.

Rigid Cervix

A rigid cervix is often observed in elderly primigravidas. Causes include poor cervical maturation, lack of elasticity, or excessive cervical contraction driven by psychological tension. These factors make cervical dilation slow and difficult.

Injection of 5–10 ml of 0.5% lidocaine on each side of the cervix has been reported to aid dilation. In cases where no improvement occurs, cesarean delivery remains necessary.

Cervical Edema

Cervical edema is often seen with a flat pelvis, persistent occipitoposterior position, or prolonged latent labor. Premature bearing down before full cervical dilation can compress the anterior cervical lip between the fetal head and the symphysis pubis, impairing blood flow and causing edema. This condition interferes with cervical dilation.

Mild cases may improve by elevating the maternal hips to reduce pressure on the cervix. Injection of 5–10 ml of 0.5% lidocaine on each side of the cervix may also help. Once the cervix is nearly fully dilated, the edematous anterior lip can be manually pushed over the fetal head, facilitating vaginal delivery.

If these measures prove ineffective, cesarean delivery is required.

Cervical Cancer

Cervical malignancies are hard and fragile. Vaginal delivery poses a significant risk of cervical tears, hemorrhage, and tumor dissemination. Cesarean delivery is recommended.

Uterine Abnormalities

Uterine Malformations

Uterine malformations, such as septate uterus, bicornuate uterus, or uterus didelphys, significantly increase the risk of labor complications. These include higher incidences of abnormal fetal positions and placental abnormalities, uterine inertia, prolonged labor, slow cervical dilation, and uterine rupture.

Pregnant individuals with uterine malformations require close monitoring during labor. Indications for cesarean delivery often need to be expanded in these cases.

Scarred Uterus

A scarred uterus can result from previous cesarean delivery, deep myomectomy, cornual or interstitial tubal resection, uteroplasty, or other surgeries. Pregnancy and labor in women with a scarred uterus carry an elevated risk of uterine rupture.

Not all individuals with a history of cesarean delivery require a subsequent cesarean section. Vaginal birth after cesarean (VBAC) can be considered on a case-by-case basis. Factors influencing VBAC eligibility include the type and indication for the previous cesarean, postoperative complications (e.g., infection), the interval between deliveries (at least 18 months), uterine incision type (e.g., low transverse incision), fetal size and position, and labor progression. With the aforementioned favorable conditions, successful VBAC rates are relatively high.

Pelvic Tumors

Uterine Fibroids

Small fibroids that do not obstruct the birth canal generally allow for vaginal delivery, with fibroid management deferred until after delivery.

Larger fibroids in the lower uterine segment or cervix can occupy the pelvis or obstruct the pelvic inlet, preventing descent of the presenting part. These cases necessitate cesarean delivery.

Ovarian Tumors

Ovarian tumors during pregnancy, due to uterine elevation, uterine contractions, and descending pressure from the presenting part, carry a higher risk of torsion or rupture.

When an ovarian tumor obstructs engagement at the pelvic inlet, cesarean delivery is required, and the ovarian tumor can be excised simultaneously.