First Stage of Labor

The first stage of labor refers to the period from the onset of active labor to full cervical dilation (10 cm). Since it can sometimes be difficult to determine the exact onset of active labor, early hospital admission may result in unnecessary interventions and an increased rate of cesarean delivery. It is generally recommended that nulliparous women be admitted to the hospital after confirmed active labor and complete cervical effacement. For multiparous women, hospital admission should occur soon after the onset of labor.

Clinical Manifestations

The first stage of labor is characterized by regular uterine contractions, cervical dilation, descent of the presenting fetal part, and rupture of membranes.

Regular Uterine Contractions

At the beginning of the first stage, uterine contractions are weak with a short duration of approximately 30 seconds and long intervals of 5–6 minutes. As labor progresses, contraction intensity increases, durations are prolonged, and intervals become shorter. By the time the cervix is fully dilated, contractions may last up to 1 minute with intervals as brief as 1–2 minutes.

Cervical Dilation

Cervical dilation manifests as gradual softening, shortening, and effacement of the cervix, accompanied by progressive enlargement of the cervical opening. Initially, the rate of dilation is slow, but it accelerates during the later stages. Once the cervix is fully dilated (10 cm), the lower uterine segment, cervix, and vaginal walls collectively form a cylindrical, soft birth canal.

Descent of the Fetal Presenting Part

The descent of the presenting part is a critical factor in determining whether a vaginal delivery is possible. As labor progresses, the presenting part gradually descends and, after the cervix dilates to 4–6 cm, descends more rapidly until it reaches the vulva and vaginal opening.

Rupture of Membranes

Following engagement of the presenting part, amniotic fluid is divided into two segments: the amniotic fluid in front of the presenting part is referred to as the forewaters. When intra-amniotic pressure increases during uterine contractions, the membranes may rupture spontaneously, causing the release of the forewaters. In spontaneous vaginal deliveries, rupture of membranes typically occurs when cervical dilation is nearly complete.

Observation and Management During Labor

Throughout the entire labor process, it is important to monitor the progress of labor, closely observe maternal and fetal well-being, identify abnormalities early, and respond appropriately.

Observation and Management of Labor Progress

Uterine Contractions

Uterine contractions include frequency, intensity, duration, interval, and uterine relaxation. Common methods for assessing contractions include abdominal palpation and instrumental monitoring.

Abdominal Palpation

This is the simplest and most essential method. The midwife places the palm on the abdominal wall of the parturient; during contractions, the uterine body feels elevated and firm, while during intervals, it becomes relaxed and soft.

Instrumental Monitoring

The most commonly used is external electronic monitoring. An intrauterine pressure transducer is placed on the uterine body via the abdominal wall and continuously records for 40 minutes. This can display the onset, peak, end, and relative intensity of contractions. Effective labor contractions are defined as 3–5 contractions within 10 minutes, sufficient to efface the cervix, dilate the cervical os, and facilitate descent of the presenting part. More than 5 contractions in 10 minutes is defined as uterine tachysystole.

Cervical Dilation and Descent of the Presenting Part

Vaginal examination is used to assess cervical dilation and fetal descent. During the latent phase, it is suggested to perform a vaginal exam every 4 hours; during the active phase, every 2 hours. The perineum is disinfected, and the examiner uses the index and middle fingers to directly assess the pelvis and birth canal, observe cervical effacement and dilation, fetal station, determine fetal position, and check for the presence of umbilical cord below the presenting part.

Fetal descent accelerates during the active phase, with an average descent rate of 0.86 cm per hour. There are two methods to assess fetal descent:

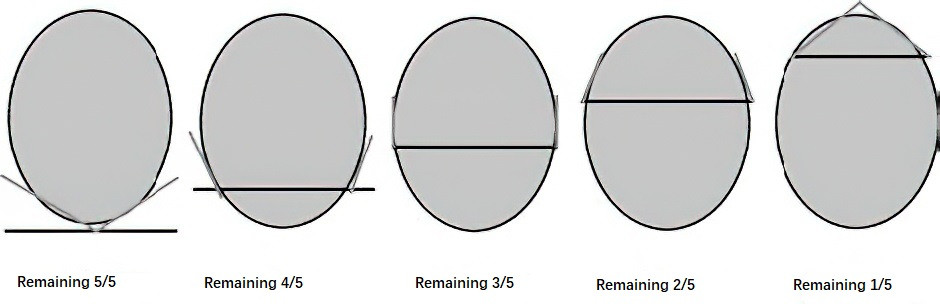

Abdominal Palpation by Fifths Rule

The portion of the fetal head palpable above the pelvic brim is estimated using the international fifths method. When both hands are placed on either side of the fetal head:

- If fingertips meet under the head, 5/5 remains;

- If fingertips converge but do not meet, 4/5 remains;

- If palms are parallel on both sides, 3/5 remains;

- If palms are slightly splayed outward, 2/5 remains;

- If wrists are touching, only 1/5 remains.

Figure 1 International "fifths" method illustration for palpating fetal head engagement at the pelvic inlet plane

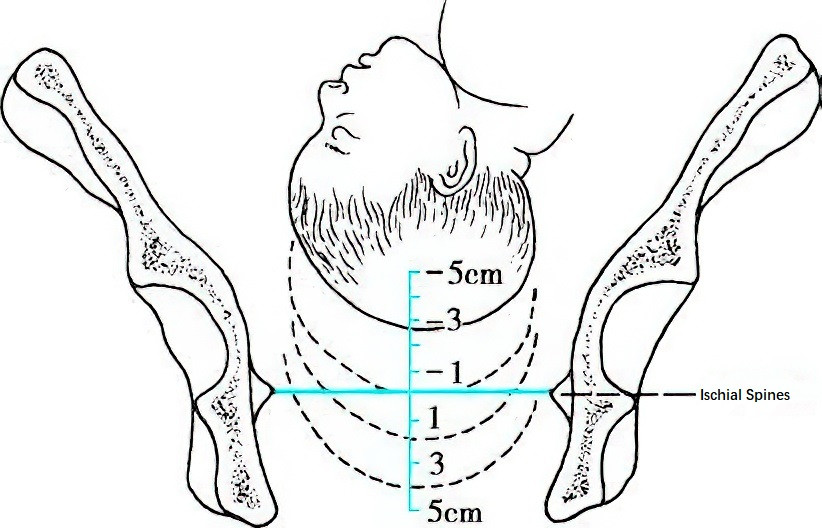

Station Relative to Ischial Spines

The lowest point of the fetal skull is compared with the level of the ischial spines during vaginal examination. When at the level of the spines, it is designated as “0”; 1 cm above is “-1”; 1 cm below is “+1”, and so on.

Figure 2 Illustration of vaginal examination for assessing fetal head station

Rupture of Membranes

Once membranes rupture, fetal heart rate should be monitored immediately, and the amniotic fluid’s characteristics (color and volume) should be observed. The time of rupture should be recorded and maternal temperature measured. If fetal heart abnormalities are detected, a vaginal exam is required to rule out umbilical cord prolapse. After membrane rupture, maternal temperature should be measured every 2 hours. Chorioamnionitis should be considered, and based on clinical indicators, the need for antibiotic prophylaxis or treatment should be determined. If no signs of infection are present, prophylactic antibiotics may be given if labor does not occur within 12 hours post rupture.

Fetal and Maternal Monitoring and Management

Fetal Heart Monitoring

Fetal heart rate should be auscultated during the interval between contractions, and frequency of monitoring should be increased as labor progresses. During the latent phase, fetal heart should be auscultated at least once every 60 minutes, and during the active phase at least once every 30 minutes. For high-risk pregnancies or suspected fetal compromise, or in cases of abnormal amniotic fluid, continuous electronic fetal monitoring is recommended to assess heart rate, baseline variability, and its relationship with uterine contractions, ensuring close surveillance of fetal status.

Maternal Observation and Management

Vital Signs

Maternal vital signs should be measured every 4 hours and recorded. Blood pressure may rise 5–10 mmHg during contractions and return to baseline during intervals. If discomfort, elevated blood pressure, or fever occurs, frequency of monitoring should be increased with appropriate assessment and management. In cases with cardiovascular, respiratory, or other systemic complications, parameters such as respiratory rate, oxygen saturation, and urine output should also be monitored.

Vaginal Bleeding

Observation should focus on the presence of abnormal vaginal bleeding, being alert to conditions such as placenta previa, placental abruption, or rupture of vasa previa.

Diet

A low-residue diet in small, frequent meals is recommended to maintain energy and ensure safety if emergency cesarean section and anesthesia are required.

Activity and Rest

If contractions are weak and membranes are intact, the parturient may move around the room. Moderate activity and upright posture in low-risk pregnancies can help shorten the first stage of labor.

Urination

The parturient should be encouraged to void every 2–4 hours to prevent bladder distension, which can interfere with contractions and fetal descent. Catheterization may be necessary if needed.

Emotional Support

Maternal emotional state can influence uterine activity and labor progress. Supporting the parturient in coping with the pain and anxiety of labor, enhancing confidence in natural delivery, and encouraging active cooperation with healthcare providers can contribute to a smoother delivery.

Second Stage of Labor

The second stage of labor refers to the period from full cervical dilation to the delivery of the fetus. Proper assessment and management during this stage are critical for maternal and neonatal outcomes. Since prolonged duration of the second stage is associated with increased adverse outcomes for both mother and fetus—such as postpartum hemorrhage, puerperal infection, severe perineal lacerations, neonatal asphyxia, or infection—the management of this stage should not focus solely on its length. Greater emphasis should be placed on fetal heart rate monitoring, uterine contractions, fetal descent, the presence or absence of cephalopelvic disproportion, and the general condition of the parturient. The goal is to avoid both prematurely changing the delivery method due to insufficient trial of labor and extending the second stage inappropriately, which could increase the risk of complications. The appropriate labor management strategy should be selected at the right time based on comprehensive evaluation.

Clinical Manifestations

Near or after full cervical dilation, the fetal membranes often rupture spontaneously. If they remain intact, fetal descent may be hindered, and artificial rupture of membranes should be performed during the interval between contractions. As the fetal head descends and compresses the pelvic floor, the parturient experiences a reflexive urge to defecate, accompanied by involuntary bearing-down efforts and breath-holding. The perineum becomes distended and thinned, and the anal sphincter relaxes.

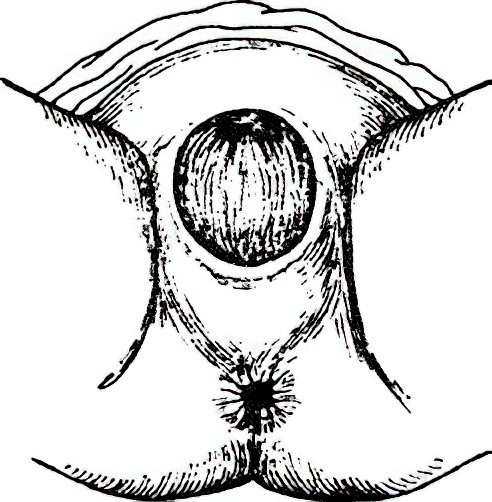

During contractions, the fetal head appears at the vaginal opening and recedes during the interval; this is referred to as “head visible on vulval gapping.” When the biparietal diameter passes the pelvic outlet and the head no longer recedes between contractions, this is called “crowning of the head.” As labor progresses, the head is delivered, followed by restitution and external rotation of the head, then sequential delivery of the anterior and posterior shoulders, and finally the rest of the body, accompanied by the outflow of remaining amniotic fluid. In multiparas, the second stage tends to be shorter, and delivery of the fetal head may occur after only a few contractions.

Figure 3 Crowning of the fetal head

Observation and Management During the Second Stage

Fetal Heart Monitoring

Due to strong and frequent contractions during this stage, the frequency of fetal heart monitoring should be increased. Monitoring should occur after every contraction or at least every 5 minutes, with auscultation performed during the interval phase for no less than 30–60 seconds. When feasible, continuous electronic fetal monitoring is recommended to assess heart rate patterns and their relationship to uterine contractions, and to distinguish fetal heart rate from maternal heart rate. If abnormalities are detected, a vaginal examination should be performed promptly to comprehensively evaluate labor progress and expedite delivery if necessary.

Uterine Contraction Monitoring

During the second stage, contractions may last up to 60 seconds with intervals of 1–2 minutes. The quality of contractions is closely related to the duration of the second stage. Oxytocin may be used when necessary to strengthen uterine contractions.

Vaginal Examination

Vaginal examinations should be conducted every hour or when abnormalities arise to assess amniotic fluid characteristics, fetal position, fetal descent, the presence of caput succedaneum, and fetal head molding. Fetal descent should first be evaluated through abdominal palpation, followed by vaginal examination to exclude cephalopelvic disproportion.

Perineal Care

Warm compresses or perineal massage may help preserve perineal integrity and reduce the risk of severe perineal lacerations. These interventions can be applied as appropriate based on the parturient’s condition.

Guidance on Bearing Down

It is recommended to provide guidance on bearing down only after the parturient naturally feels the urge to push, in order to make effective use of intra-abdominal pressure. However, for primiparas using neuraxial analgesia, bearing-down efforts should begin at the onset of the second stage under guidance to reduce the risk of chorioamnionitis and neonatal acidosis. If fetal descent is abnormal, the effectiveness of the bearing-down technique should be evaluated and corrected as needed. The method involves having the parturient place both feet against the delivery bed, hold the bed handles, inhale deeply during contractions, and bear down as if having a bowel movement to increase intra-abdominal pressure. During contraction intervals, the parturient should breathe freely and relax all muscles. When the next contraction begins, the same bearing-down maneuver is repeated to facilitate labor progression.

Delivery

Preparation for Delivery

When the cervix is fully dilated in primiparas or dilated to more than 5 cm in multiparas with regular and effective contractions, the parturient should be transferred to the delivery bed for preparation. The neonatal radiant warmer should be preheated in advance. Typically, the parturient is positioned supine on the delivery bed with the head elevated and feet lowered, legs flexed and separated to expose the perineal area. The perineum is disinfected 2 to 3 times in the following order: labia majora, labia minora, mons pubis, inner upper third of the thighs, perineum, and area around the anus. Sterile drapes are placed beneath the buttocks.

Delivery Process

Key Points

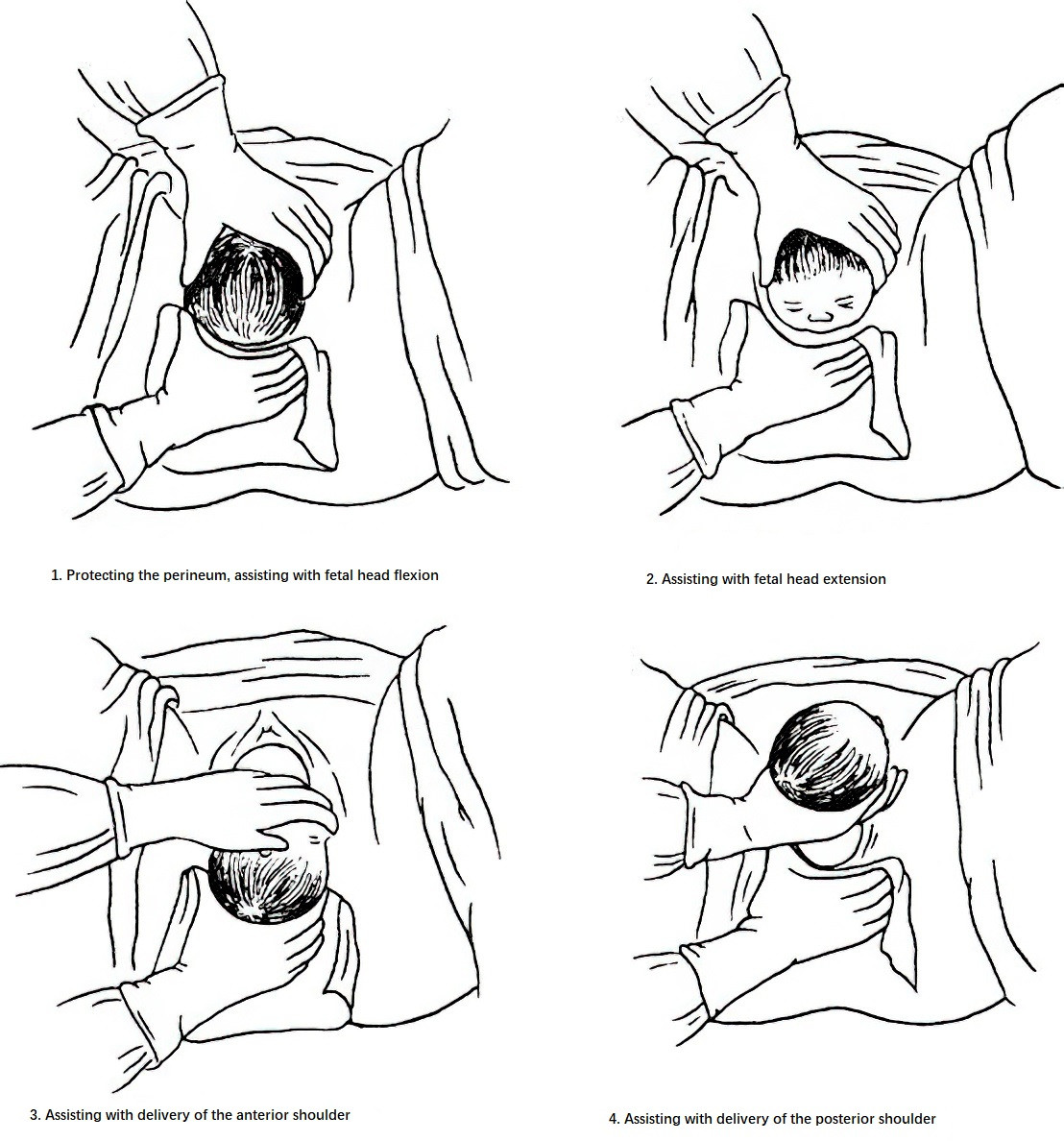

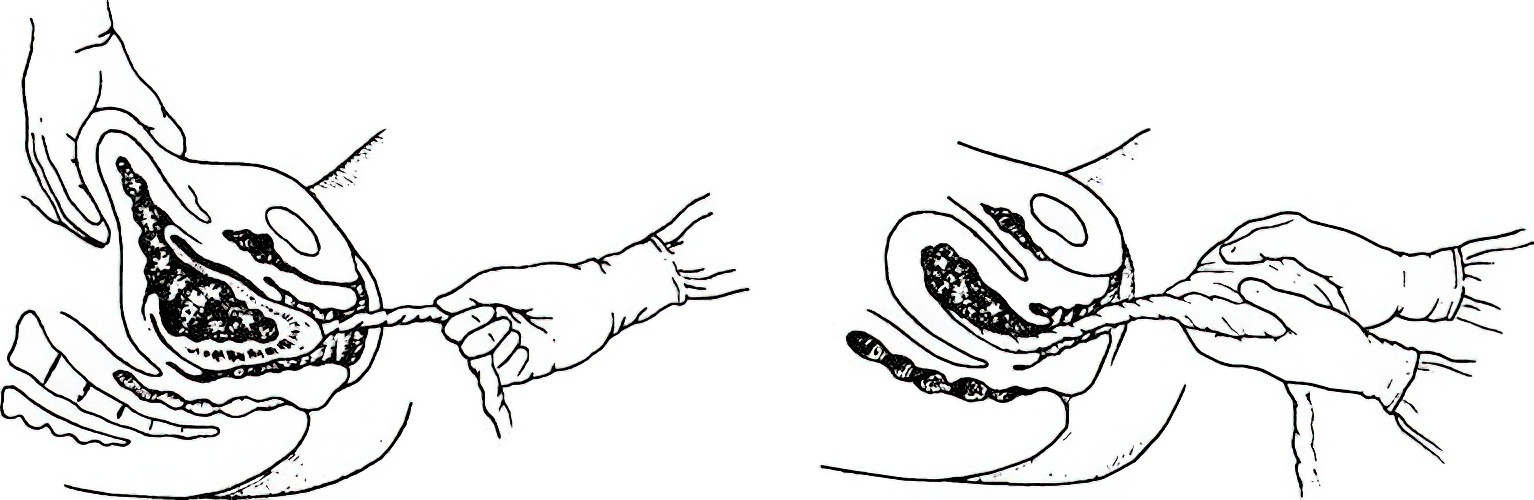

It is important to provide an explanation of the delivery process to gain the parturient’s cooperation. During delivery, the practitioner assists in promoting flexion of the fetal head, controls the speed of delivery, and protects the perineum appropriately. The goal is to allow the smallest diameter of the fetal head (suboccipitobregmatic diameter) to pass slowly through the vaginal opening to reduce the risk of severe perineal lacerations.

Delivery Steps

The practitioner stands facing the parturient. When a contraction begins and the parturient feels a bearing-down urge, guidance on how to push is provided. At crowning, instructions on when to push and when to breathe are given. Factors such as perineal edema, tight perineum, inflammation, low pubic arch, large fetus, or rapid delivery can increase the risk of perineal lacerations. A preliminary assessment should be made before delivery. Individualized guidance on pushing is provided during delivery, with manual control of the head’s delivery. The left hand gently presses on the occiput to assist with flexion, allowing the biparietal diameter to emerge gradually. If delivery is too rapid, there is a risk of perineal tearing. When the occiput is visible under the pubic arch, the parturient is guided to bear down gently during the contraction interval while the left hand assists in extending the head for a slow delivery. The mouth and nose are cleared of mucus.

Figure 4 Delivery steps

After the head is delivered, the shoulders should not be delivered immediately. It is better to wait for the next contraction to allow spontaneous restitution and external rotation, aligning the shoulders with the anteroposterior diameter of the pelvic outlet. During the next contraction, the right hand supports the perineum while the left hand gently pulls downward on the fetal neck to deliver the anterior shoulder under the pubic arch. Then, by lifting the neck upward, the posterior shoulder is delivered from the front edge of the perineum. After both shoulders are delivered, the perineal support is released and both hands assist in delivering the rest of the body. After the fetus is delivered, a container is placed beneath the buttocks to measure postpartum blood loss.

Restrictive Episiotomy

Routine episiotomy in primiparas is not recommended. Perineal protection is preferred to reduce trauma. Episiotomy should only be considered under certain conditions, such as a tight perineum or a large fetus when tearing is deemed inevitable, or when pathological conditions in the mother or fetus require expedited delivery. The decision to perform an episiotomy during forceps or vacuum-assisted delivery depends on maternal-fetal conditions and the experience of the practitioner. It is usually performed at crowning or when operative delivery is planned to minimize bleeding.

Episiotomy and Suture

After pudendal nerve block combined with local anesthesia of the perineum becomes effective, two common types of episiotomy are used:

- Postero-lateral Episiotomy: Most commonly performed on the left side. During a contraction, the practitioner inserts the index and middle fingers of the left hand into the vagina to support the left vaginal wall. Using scissors in the right hand, an incision is made at a 45° angle from the midline of the posterior commissure toward the left and rear, measuring 4–5 cm in length.

- Median Episiotomy: During a contraction, a vertical incision about 2 cm long is made from the posterior commissure along the midline. This method results in less tissue damage, minimal bleeding, and less postoperative swelling and pain. However, it carries a risk of spontaneous extension into the anal sphincter. It is not suitable for large fetuses or less experienced practitioners. Gauze is applied to the incision site to stop bleeding before fetal delivery. After the delivery of the fetus and placenta, the incision is sutured with attention to hemostasis and anatomical restoration.

Delayed Umbilical Cord Clamping

It is recommended that umbilical cord clamping be delayed by at least 30 to 60 seconds after birth in term and preterm infants who do not require resuscitation. This facilitates placental blood transfer to the newborn, increases neonatal blood volume and hemoglobin concentration, helps stabilize circulation in preterm infants, and reduces the risk of intraventricular hemorrhage.

Third Stage of Labor

The third stage of labor refers to the placental delivery period, beginning after the fetus is born and ending with the expulsion of the placenta. This stage typically lasts 5 to 15 minutes and should not exceed 30 minutes.

Clinical Manifestations

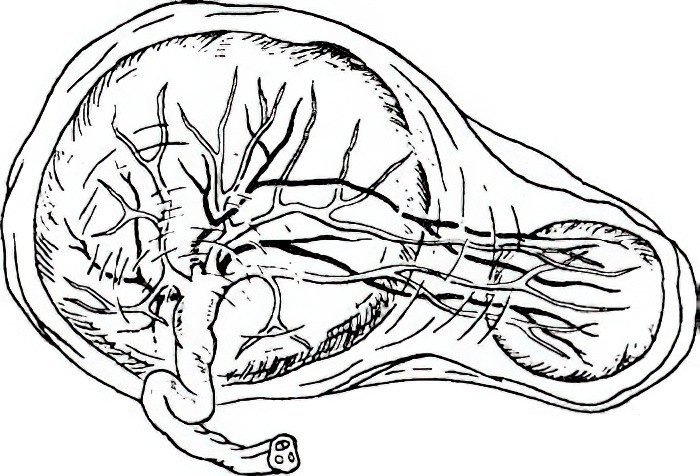

After delivery of the fetus, the uterine cavity volume decreases significantly, causing a mismatch between the placenta and the uterine wall, leading to placental separation. Bleeding from the separation site forms a hematoma, and continued uterine contractions result in complete placental detachment and expulsion.

Figure 5 Uterine shape during placental separation

Signs of placental separation include:

- The uterus becomes firm and globular; after separation, the placenta descends into the lower uterine segment, causing it to distend while the uterine body becomes elongated and rises upward, with the fundus reaching above the umbilicus.

- The portion of the umbilical cord visible at the vaginal opening lengthens on its own.

- A small amount of vaginal bleeding occurs.

- When the ulnar side of the hand is used to gently press the lower uterine segment just above the pubic symphysis, the uterus rises and the umbilical cord does not retract.

Once separated, the placenta is expelled through the vagina.

There are two modes of placental separation and expulsion:

- Fetal-Side Presentation (Schultze mechanism): This is more common. Separation begins from the center of the placenta, and the fetal side presents first. It is typically characterized by placental expulsion followed by a small amount of bleeding.

- Maternal-Side Presentation (Duncan mechanism): Less common. Separation starts from the edge, and the maternal side presents first. Blood flows along the separation plane, resulting in more vaginal bleeding before placental expulsion.

Management

Neonatal Care

General Care

After birth, the newborn is placed under a radiant warmer, dried, and kept warm.

Airway Clearance

If there is excessive secretion in the oral cavity or airway obstruction, a suction bulb may be used to remove mucus and amniotic fluid. If the airway is clear but the newborn does not cry, gentle back rubbing or tapping the soles of the feet may stimulate breathing. Once the newborn cries, umbilical cord care can proceed.

Apgar Score and Umbilical Arterial Blood Gas Analysis

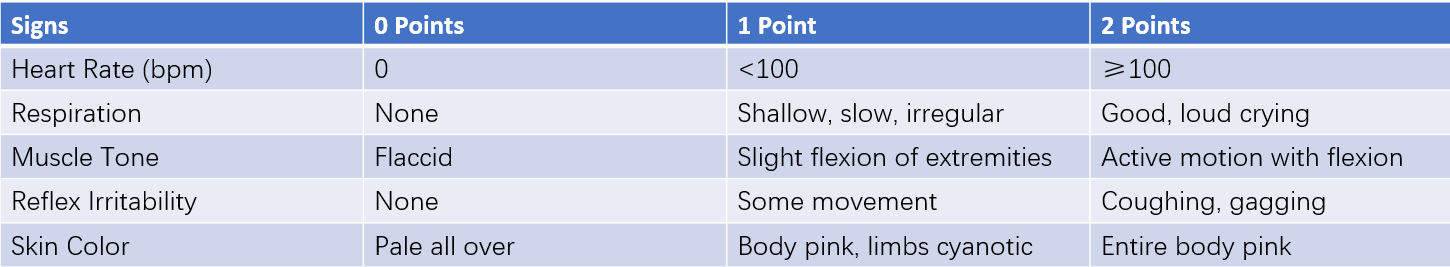

The Apgar score is a rapid method to assess the newborn's general condition and guide resuscitation. It consists of five components: heart rate, respiration, muscle tone, reflex irritability, and skin color. Each item is scored 0, 1, or 2, and the total is the Apgar score.

- The 1-minute Apgar score reflects the newborn’s condition at birth and intrauterine status, but resuscitation should not be delayed to wait for the score.

- The 5-minute score reflects the effectiveness of resuscitation and correlates with both short- and long-term prognosis.

Table 1 Newborn Apgar scoring system

Umbilical artery blood gas analysis reflects the fetus's acid–base status during labor and provides objective and specific information on hypoxia and acidosis, representing the physiological basis of asphyxia more precisely than the Apgar score.

Criteria for Neonatal Asphyxia:

- 1- or 5-minute Apgar score ≤7 with ineffective spontaneous respiration.

- Umbilical arterial pH <7.15.

- Exclusion of other causes of low Apgar score.

- Presence of prenatal high-risk factors for asphyxia.

The first three are necessary conditions; the fourth is a reference.

Umbilical Cord Care

After cutting the cord, it should be tied 0.5 cm above the umbilical stump using silk thread, an elastic ring, or a cord clamp. The stump is then disinfected and wrapped with sterile gauze. Secure tying is essential to prevent bleeding.

Other Care Measures

A physical examination is conducted, and footprints of the newborn and a thumbprint of the mother are recorded in the medical chart. An identification band is placed on the newborn’s wrist and swaddling cloth, indicating gender, weight, time of birth, and mother’s name. Early breastfeeding is supported.

Assisting Placental Expulsion

Proper management of placental delivery is essential to prevent postpartum hemorrhage. After the anterior shoulder of the fetus is delivered, 10–20 units of oxytocin diluted in 250–500 ml of normal saline should be infused rapidly intravenously. Controlled cord traction is applied once placental separation is confirmed. The uterine fundus is stabilized with the left hand—thumb on the anterior wall and other fingers on the posterior wall—while the right hand gently pulls the umbilical cord. When the placenta reaches the vaginal opening, it is cupped with both hands and gently rotated in one direction to assist the membranes in detaching and delivering intact. If the membranes tear during expulsion, the torn edge is grasped with a hemostat and traction is continued in the same direction until complete expulsion is achieved.

Figure 6 Assisting with delivery of placenta and membranes

Inspection of Placenta and Membranes

The placenta is spread flat for inspection. The maternal surface is checked for any missing lobules. The membranes are lifted to verify completeness. The fetal side is inspected, especially the edges, for ruptured vessels and any evidence of accessory (succenturiate) lobes.

Figure 7 Accessory placenta

Examination of the Soft Birth Canal

Following placental delivery, the perineum, inner labia, area around the urethral opening, vaginal wall, and cervix should be examined for lacerations. Any identified tears should be sutured promptly.

Prevention of Postpartum Hemorrhage

To minimize postpartum blood loss, uterotonic agents such as oxytocin should be administered after the delivery of the anterior shoulder and combined with uterine massage to enhance uterine contractions. Blood loss should be carefully monitored and accurately measured.

Observation of General Postpartum Condition

The two hours following placental expulsion constitute a high-risk period for postpartum hemorrhage, often referred to as the "fourth stage of labor." During this time, the parturient should be observed in the delivery room for general condition, facial appearance, conjunctival and nail bed color, blood pressure, pulse, and vaginal bleeding. Uterine contractions, fundal height, bladder distension, and the presence of perineal or vaginal hematomas should be noted. Any abnormalities should be managed promptly. If no issues arise after two hours, the mother and newborn may be transferred to the ward.