Placental abruption refers to the premature separation of a normally implanted placenta from the uterine wall, partially or completely, after 20 weeks of gestation and before the delivery of the fetus. The incidence is approximately 1%. It is a severe complication in late pregnancy, characterized by rapid progression, and may pose a serious threat to both maternal and fetal lives if not managed promptly.

Etiology

The exact pathogenesis remains unclear, but it is considered to be associated with the following factors:

Vascular Disorders

Conditions such as hypertensive disorders of pregnancy—particularly severe preeclampsia, chronic hypertension, chronic kidney disease, or systemic vascular pathologies—may lead to spasm or sclerosis of the spiral arterioles in the decidua basalis. This can result in distal capillary degeneration, necrosis, or even rupture and bleeding. Hematoma formation between the decidua and placenta causes the placenta to detach from the uterine wall. In mid to late pregnancy or during labor, the gravid uterus may compress the inferior vena cava, reducing venous return and lowering blood pressure. Venous congestion in the uterus may elevate venous pressure, leading to rupture of decidual veins and formation of retroplacental hematoma, contributing to partial or complete placental separation.

Mechanical Factors

Trauma, especially blunt abdominal trauma, can trigger abrupt placental separation due to sudden uterine stretching or contraction. This usually occurs within 24 hours after the injury.

Sudden Reduction in Intrauterine Pressure

Premature rupture of membranes before term; rapid delivery of the first twin in twin pregnancies; or rapid drainage of amniotic fluid following artificial rupture of membranes in cases of polyhydramnios can cause an abrupt drop in intrauterine pressure. This may lead to sudden uterine contraction and displacement of the placenta from the uterine wall.

Other factors

Advanced maternal age, multiparity, and a history of placental abruption significantly increase the risk of recurrence. Additional contributing factors may include smoking, substance abuse, chorioamnionitis, assisted reproductive technology, and a predisposition to thrombosis.

Pathology and Pathophysiology

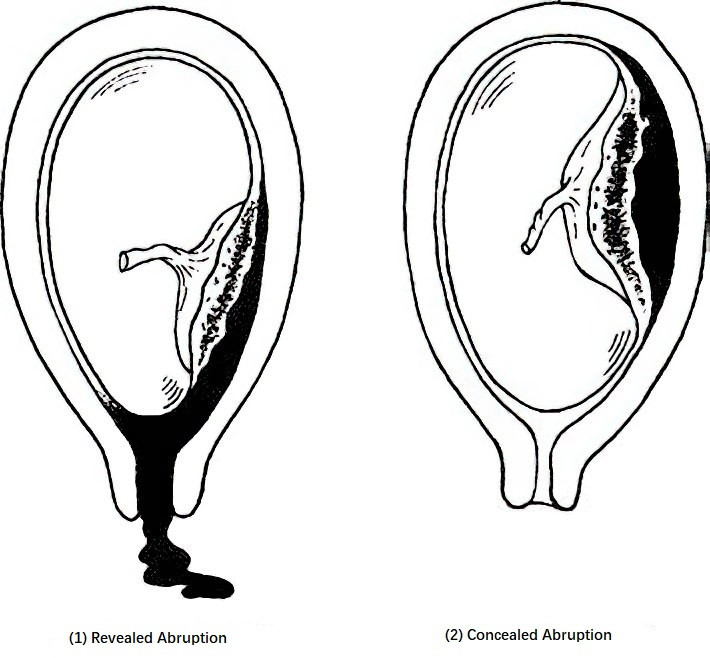

The primary pathological change is hemorrhage in the decidua basalis, resulting in hematoma formation and subsequent separation of the placenta from the uterine wall. When the area of separation is small, bleeding may stop as the blood clots, and clinical symptoms may be absent or mild. Continued bleeding can expand the area of separation and lead to a large retroplacental hematoma. If blood escapes through the edge of the placenta and membranes via the cervical canal, the condition is termed revealed abruption. If the edges of the placenta or membranes remain attached to the uterine wall, or if the fetal head descends into the pelvis and compresses the lower edge of the placenta, accumulated blood remains trapped behind the placenta, with no vaginal bleeding—this is called concealed abruption.

Figure 1 Types of placental abruption

In cases of rapidly increasing internal bleeding, accumulated blood behind the placenta elevates pressure, infiltrating the myometrium and causing muscle fiber separation, rupture, or degeneration. When the blood reaches the serosal layer, bluish-purple ecchymoses appear on the uterine surface, most prominently at the site of placental attachment, a condition known as uteroplacental apoplexy or Couvelaire uterus. Blood may also infiltrate the subepithelial layers of the ovaries, the mesosalpinx, and the broad ligament. Large amounts of tissue thromboplastin released from the separated placental villi and decidua enter the maternal circulation, activating the coagulation cascade and impairing blood supply, potentially leading to multiple organ dysfunction. As procoagulant substances continue to enter the bloodstream, the fibrinolytic system is activated, producing a large quantity of fibrin degradation products (FDPs) and causing secondary hyperfibrinolysis. This process consumes large amounts of clotting factors, ultimately resulting in coagulopathy.

Clinical Manifestations and Classification

The typical clinical presentation includes vaginal bleeding and abdominal pain, which may be accompanied by increased uterine tone and uterine tenderness, particularly at the site of placental separation. Vaginal bleeding is typically dark and non-clotting, but the amount may not correlate with the degree of pain or placental separation, especially in concealed abruption involving a posterior placenta. Fetal heart rate abnormalities are often the earliest sign, and the uterus may remain hypertonic between contractions. Fetal position may be difficult to palpate. In severe cases, the uterus becomes board-like and highly tender, fetal heart rate changes or disappears, and symptoms such as nausea, vomiting, sweating, pallor, weak pulse, and hypotension may indicate shock. Clinical evaluation of severity is commonly based on a grading system for placental abruption.

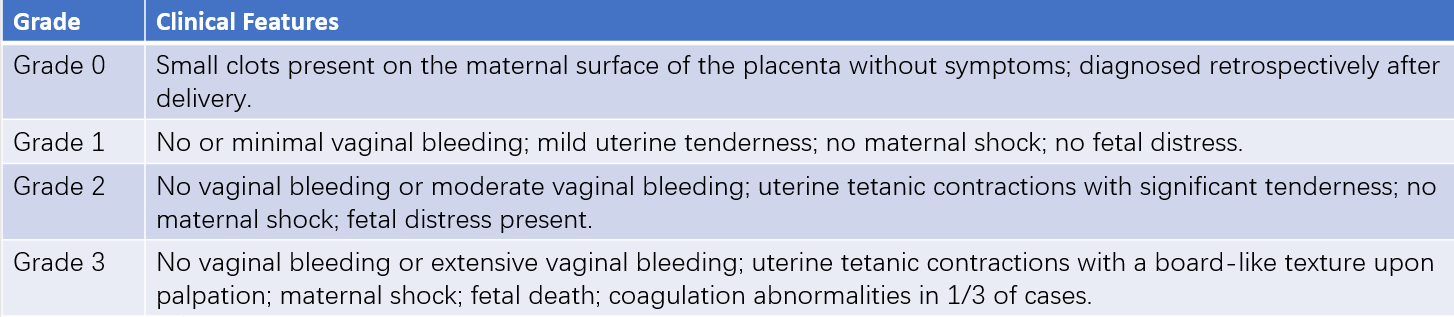

Table 1 Classification criteria for placental abruption

Note: Grade 0 or 1 placental abruption is commonly associated with partial or marginal separation of the placenta, while Grade 2 or 3 abruption is often related to complete or central placental separation.

Auxiliary Examinations

Ultrasound Examination

Ultrasound can provide insights into the location of the placenta and the type of placental abruption, as well as clarify the size and viability of the fetus. Typical sonographic findings may include a hypoechoic area with unclear boundaries between the placenta and the uterine wall, indicative of a retroplacental hematoma, abnormal thickening of the placenta, or "round" separation at the placental edge. It is important to acknowledge that a negative ultrasound result does not completely rule out placental abruption, particularly when the placenta is attached to the posterior uterine wall.

Electronic Fetal Heart Rate Monitoring

This tool aids in assessing the intrauterine status of the fetus. Signs include loss of baseline variability in fetal heart rate, variable decelerations, late decelerations, sinusoidal patterns, or fetal bradycardia.

Laboratory Tests

Tests include a complete blood count, platelet count, coagulation profile, liver and kidney function tests, and electrolyte levels. For grade 3 cases, renal function and blood gas analysis should be assessed. Suspicious results from screening for disseminated intravascular coagulation (DIC) warrant confirmation through fibrinolysis tests (including thrombin time, euglobulin lysis time, and protamine sulfate test). Plasma fibrinogen levels below 250 mg/dL are abnormal, with levels under 150 mg/dL being diagnostic for coagulopathy. In emergency situations, 2 mL of blood can be drawn from the cubital vein into a dry test tube; the absence of clot formation or the presence of soft, easily fragmented clots after 7 minutes suggests coagulation dysfunction.

Diagnosis and Differential Diagnosis

Clinical diagnosis relies on the patient's medical history, symptoms, signs, and findings from laboratory and ultrasound examinations. When placental abruption is suspected, recording uterine fundal height on the abdominal surface can assist in monitoring changes.

Clinical presentations of grade 0 and grade 1 abruption are atypical. Ultrasound can aid diagnosis, and differentiation from placenta previa may be necessary. Close observation of symptom progression and coagulation status is essential.

Grade 2 and grade 3 abruption typically have more pronounced symptoms and signs, making diagnosis easier, with the primary differentiation from impending uterine rupture.

Complications

Fetal Distress or Fetal Death

Large areas of placental detachment and significant hemorrhage can lead to fetal distress or death due to hypoxia or ischemia.

Disseminated Intravascular Coagulation (DIC)

Placental abruption is the most common obstetric cause of coagulation disorders. Clinical manifestations include bleeding from the skin, mucosa, or injection sites; prolonged vaginal bleeding with incomplete clot formation or soft clots; and, in severe cases, hematuria, hemoptysis, or hematemesis. High mortality rates are associated with DIC, so prevention is crucial.

Hemorrhagic Shock

Significant blood loss, whether from external (revealed) or internal (concealed) bleeding, can lead to shock. Uteroplacental apoplexy can impair uterine muscle contraction, resulting in severe postpartum hemorrhage. Coagulopathy exacerbates bleeding, and DIC complications make postpartum hemorrhage difficult to control, causing shock, multi-organ failure, pituitary and adrenal cortical necrosis, and potentially leading to Sheehan syndrome.

Acute Kidney Failure

Massive blood loss from placental abruption may severely reduce renal perfusion, causing ischemic necrosis of the renal cortex or tubules.

Amniotic Fluid Embolism

Amniotic fluid may enter maternal circulation through the open uterine vessels at the site of placental detachment, triggering amniotic fluid embolism.

Impact on the Mother and Fetus

Placental abruption has significant adverse effects on both the mother and fetus. There is an increased rate of cesarean sections, anemia, postpartum hemorrhage, and DIC. Acute fetal hypoxia caused by placental abruption-related hemorrhage results in markedly elevated rates of neonatal asphyxia, preterm birth, and stillbirth. Perinatal mortality is approximately 11.9%, 25 times higher than that of pregnancies without placental abruption. More severely, surviving neonates may suffer from long-term neurological developmental impairments and other complications.

Treatment

Placental abruption poses a severe risk to maternal and fetal life. The prognosis for both depends on whether management is timely and appropriate. The principles of treatment involve early recognition, correction of shock, prompt termination of pregnancy, and prevention and management of complications.

Correction of Shock

Continuous monitoring of maternal vital signs is necessary. Aggressive blood transfusion, rapid replenishment of blood volume, and clotting factors help stabilize systemic circulation. The type of blood products to be transfused, including red blood cells, plasma, platelets, and cryoprecipitate, is determined based on hemoglobin levels. Early correction of coagulation dysfunction is crucial in cases of disseminated intravascular coagulation (DIC). Hematocrit levels should be maintained above 0.30, hemoglobin levels at approximately 100 g/L, and urine output above 30 mL/h.

Monitoring of Fetal Intrauterine Status

Continuous monitoring of fetal heart rate is essential for assessing intrauterine fetal well-being. Pregnant individuals with a history of trauma and suspected placental abruption need continuous fetal heart rate monitoring to identify placental abruption early.

Prompt Termination of Pregnancy

Confirmed cases of grade 2 or grade 3 placental abruption require immediate termination of pregnancy. The mode of delivery depends on the severity of the maternal condition, fetal status, progression of labor, and fetal presentation.

Vaginal Delivery

This is appropriate for patients with grades 0 to 1 abruption who are in generally good condition, whose cases are mild and primarily involve external bleeding, and where cervical dilation suggests delivery will be completed in a short time. Artificial rupture of membranes may be performed, allowing amniotic fluid to drain slowly to reduce uterine volume. Oxytocin infusion might be utilized to shorten the second stage of labor if needed. Continuous monitoring of heart rate, blood pressure, uterine fundal height, vaginal bleeding, and fetal status during labor is critical. If abnormalities occur, cesarean delivery may be indicated.

For pregnancies between 20–34 weeks gestation with grade 1 abruption and stable intrauterine fetal status, conservative management can be used to prolong gestation. Antenatal corticosteroids may be administered before 34 weeks to promote fetal lung maturation. Close monitoring of placental abruption progression is mandatory, with immediate delivery initiated upon significant vaginal bleeding, uterine hypertonicity, coagulopathy, or signs of fetal distress.

Cesarean Section

This is indicated in:

- Grade 1 abruption with signs of fetal distress;

- Grade 2 abruption in cases where vaginal delivery cannot be completed shortly;

- Grade 3 abruption with maternal deterioration, intrauterine fetal death, or the inability to deliver vaginally;

- Lack of progress in labor following membrane rupture;

- Severe maternal deterioration threatening life irrespective of fetal viability.

During cesarean section, oxytocin is administered immediately after the fetus and placenta are delivered to promote uterine contraction, and the placenta is manually removed if necessary. For uteroplacental apoplexy, uterine massage and warm saline gauze packs can be applied to the uterus to improve contraction and reduce bleeding. In cases of intractable bleeding and DIC, aggressive blood transfusion and coagulation factor supplementation are critical, with hysterectomy as a last resort if bleeding remains uncontrolled.

Management of Complications

Postpartum Hemorrhage

Uterotonics such as oxytocin, prostaglandin preparations, or methylergometrine should be administered after delivery. Efforts must be made to facilitate placental separation and prevent DIC. Persistent uterine bleeding or soft, uncoagulated clots should be addressed as coagulopathy. Additional interventions such as uterine compression, arterial ligation, embolization, or hysterectomy may be required if bleeding persists.

Coagulopathy

Prompt termination of pregnancy and interruption of procoagulant substances entering maternal circulation is necessary. Coagulation dysfunction should be corrected through blood volume and clotting factor replenishment, along with the transfusion of proportional amounts of red blood cells, plasma, and platelets as needed. Cryoprecipitate may be administered to supplement fibrinogen if necessary.

Acute Kidney Failure

Oliguria (<30 mL/h) or anuria (<100 mL/24h) indicates insufficient blood volume, necessitating prompt fluid resuscitation. If urine output remains below 17 mL/h despite adequate resuscitation, intravenous furosemide (20–40 mg) may be administered, with additional doses repeated as required. Electrolyte and acid-base balance should be monitored closely. Persistent reductions in urine output, combined with rising blood urea nitrogen, creatinine, and potassium levels and reduced carbon dioxide-binding capacity, suggest impending kidney failure. Hemodialysis is warranted if uremia develops.

Prevention

Strengthening the maternal healthcare system, particularly in the management and treatment of preeclampsia, chronic hypertension, and kidney disease during pregnancy, is essential. Pregnant individuals should adopt healthy lifestyle habits, prevent intrauterine infections, and avoid abdominal trauma. External cephalic version is not recommended for cases with high-risk breech pregnancies. When performed, maneuvers for correcting fetal position should be gentle. Amniocentesis should be conducted under ultrasound guidance, avoiding the placenta if possible. In late pregnancy or during labor, pregnant individuals should engage in moderate physical activity and avoid prolonged supine positioning. Artificial rupture of membranes should occur during uterine contraction intervals, with amniotic fluid drainage slowed to prevent rapid uterine contraction.