Multiple pregnancy refers to a pregnancy in which the uterine cavity contains two or more fetuses simultaneously, with twin pregnancy being the most common type. The incidence of multiple pregnancy has significantly increased with the widespread use of assisted reproductive technologies. Multiple pregnancies are associated with a higher risk of complications, including hypertensive disorders of pregnancy, intrahepatic cholestasis of pregnancy, anemia, preterm premature rupture of membranes (PPROM), preterm birth, postpartum hemorrhage, and abnormal fetal development. Monochorionic twin pregnancies carry additional risks of unique complications such as twin-to-twin transfusion syndrome (TTTS) and selective intrauterine growth restriction (sIUGR). As a result, multiple pregnancy is classified as a high-risk pregnancy. This discussion will focus specifically on twin pregnancy.

Types and Characteristics of Twin Pregnancy

Dizygotic Twins

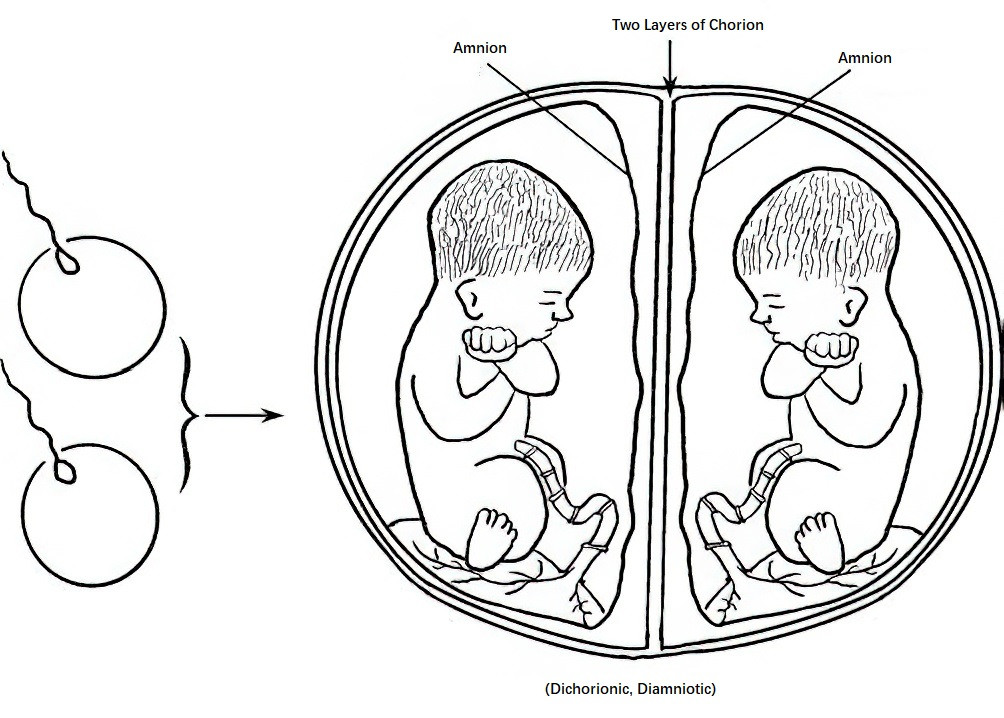

Dizygotic twins result from the fertilization of two separate ova, accounting for approximately two-thirds of twin pregnancies. This type is associated with factors such as ovulation-stimulating medications, multiple embryo transfers during in vitro fertilization (IVF), and genetic predisposition. The fertilization of two ova produces two zygotes, and the resulting fetuses have distinct genetic information. Dizygotic twins may be of the same or different sexes and often exhibit different biological characteristics. Typically, there are two placentas, though these may fuse into a single placenta with independent blood circulations for each fetus. On the fetal side of the placenta, there are two amniotic sacs separated by two layers of chorion and two layers of amnion. Superfecundation, wherein two ova are fertilized at different times within a short period, can also lead to dizygotic twins, even from different paternal origins.

Figure 1 Diagram of placenta and fetal membranes in dizygotic twins

Monozygotic Twins

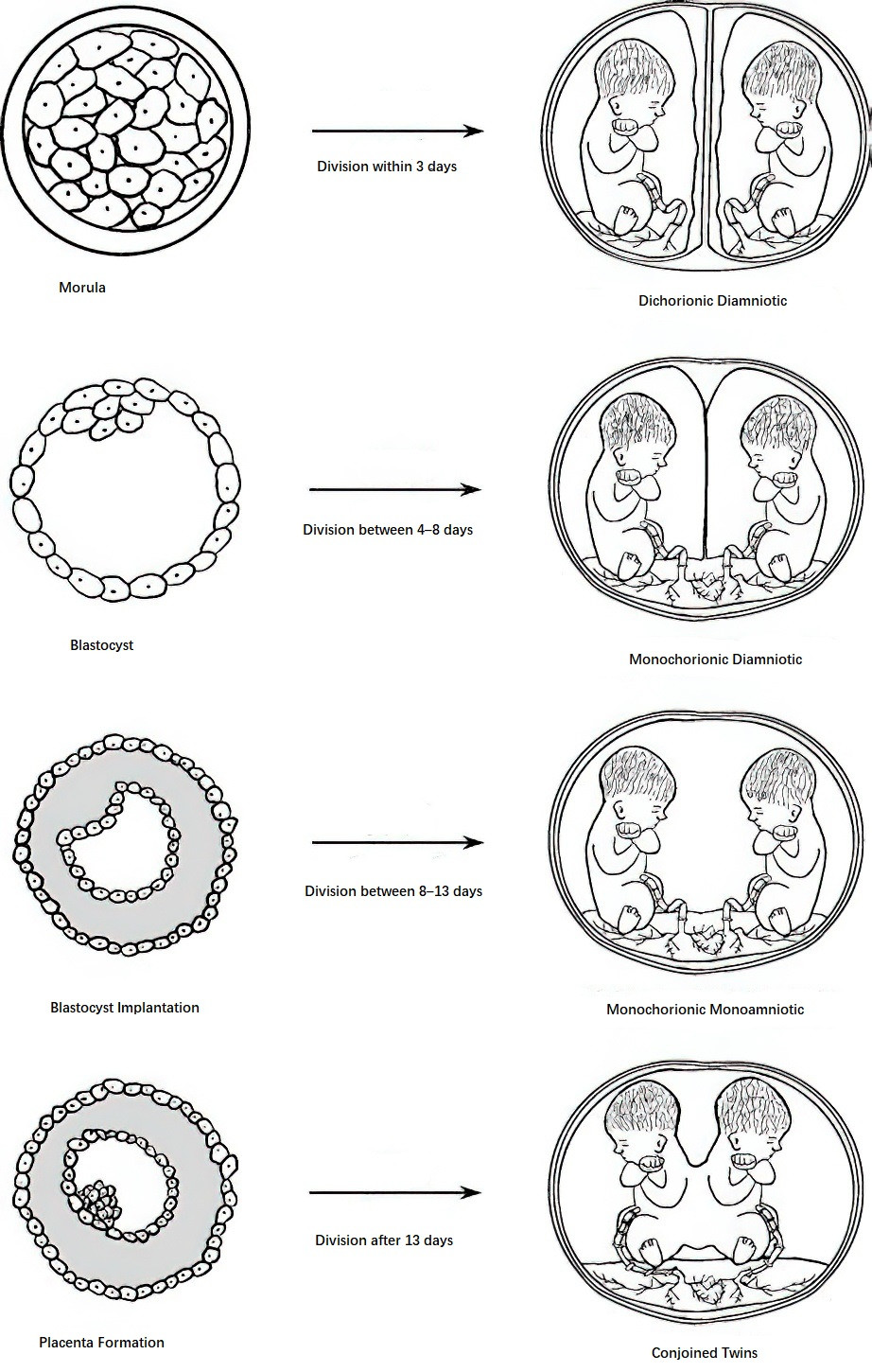

Monozygotic twins originate from the division of a single fertilized ovum and account for approximately one-third of twin pregnancies. The exact cause remains unknown and appears unaffected by race, maternal age, or parity. A single fertilized ovum splits to form two fetuses with nearly identical genetic information, which are usually of the same sex and exhibit similar biological characteristics. Depending on the timing of the division during early embryonic development, four types of monozygotic twins can form:

Figure 2 Types of fetal membranes in monozygotic twins formed at different stages of zygote division

Dichorionic Diamniotic (Di-Di) Twins

Division occurs during the morula stage (early blastocyst stage) within three days after fertilization. Each embryo develops independently, forming two amniotic sacs separated by two chorionic layers and two amniotic layers. The placentas may be two separate entities or may fuse into one. This type constitutes approximately one-third of monozygotic twins.

Monochorionic Diamniotic (Mo-Di) Twins

Division occurs between 4 to 8 days post-fertilization, when trophoblast differentiation has begun but before amnion formation. A single placenta is shared, with two amniotic sacs separated only by two layers of amnion. This type accounts for approximately two-thirds of monozygotic twins.

Monochorionic Monoamniotic (Mo-Mo) Twins

Division occurs between 8 to 13 days after fertilization, after the amniotic sac has formed. Both fetuses share a single amniotic cavity and a single placenta. This very rare type constitutes 1% to 2% of monozygotic twin pregnancies.

Conjoint Twins

Division occurs after 13 days post-fertilization, when the primitive embryonic disc has already formed, preventing complete separation of the embryos. This extremely rare type results in various forms of conjoined twins, such as shared thoracic or cranial structures. Parasitic twins, a subtype of conjoined twins, occur when a poorly developed inner cell mass becomes enclosed within a normally developing twin, often located in the upper retroperitoneal region of the dominant twin’s abdomen. The incidence of conjoined twins is approximately 1 in 1,500 monozygotic twin pregnancies.

Diagnosis

Medical History and Clinical Presentation

Dizygotic twins may be associated with a family history of twinning, prior use of ovulation-stimulating drugs, or multiple embryo transfers during in vitro fertilization. However, not all twins resulting from embryo transfer are dizygotic; cases exist in which one of the transferred embryos fails to survive, and the remaining embryo splits into monochorionic twins. Twin pregnancies are often associated with more severe nausea and vomiting during early pregnancy. After the second trimester, maternal weight gain is significant, abdominal enlargement is pronounced, and compression symptoms such as leg edema and varicose veins occur earlier and more severely. In late pregnancy, shortness of breath and limited physical mobility are common.

Obstetric Examination

Findings during examination may include a uterine size larger than expected for gestational age, palpation of multiple small fetal parts or three or more fetal poles in the second or third trimester, and smaller-than-expected fetal head sizes relative to uterine size. Two fetal heartbeats may be auscultated in distinct locations, separated by a zone without heart sounds. Common fetal presentations in twin pregnancies include both heads presenting or one head and one breech.

Ultrasound Examination

Ultrasound has important applications in determining chorionicity, prenatal screening and diagnosis, fetal growth assessment, and monitoring fetal well-being during twin pregnancies.

Chorionicity Assessment

Chorionicity assessment is crucial, particularly in early pregnancy, as monochorionic twins are associated with higher rates of complications. Between 6 to 10 weeks of gestation, the number of gestational sacs within the uterine cavity can provide clues: two sacs typically suggest dichorionic twins, while a single sac indicates a greater likelihood of monochorionic twins. Between 10 to 14 weeks, the “lambda sign” or “T-sign” at the membrane-placenta interface allows for differentiation: the former often suggests dichorionic twins, while the latter is more indicative of monochorionic twins. After the first trimester, determining chorionicity becomes more challenging and requires evaluating factors such as fetal sex, inter-amniotic membrane thickness, and whether there are separate placentas.

Prenatal Screening and Diagnosis

First-trimester ultrasound screening at 11 to 13+6 weeks can measure nuchal translucency (NT) to assess the risk of Down syndrome and detect certain severe fetal abnormalities. Screening strategies differ between twins and singletons:

- Conventional serum screening in early or mid-pregnancy is not recommended due to a high false-positive rate.

- Ultrasound NT measurements combined with maternal age or early-pregnancy serum screening can assess the risk of Down syndrome.

- Fetal cell-free DNA testing from maternal plasma offers high sensitivity and specificity for Down syndrome in twin pregnancies, with screening performance comparable to singleton pregnancies.

Indications for invasive prenatal diagnosis in twins are similar to those for singletons. In dichorionic twins, sampling is performed for both fetuses. In monochorionic twins, sampling may be done for one fetus, but if structural abnormalities or significant growth discrepancies are present, both fetuses may require sampling.

Complications

Maternal and Fetal Complications

Hypertensive Disorders of Pregnancy

The incidence is three to four times higher than that of singleton pregnancies. Onset is often earlier, and severity is greater, with a higher likelihood of complications involving the heart and lungs, as well as eclampsia.

Intrahepatic Cholestasis of Pregnancy (ICP)

The incidence is approximately twice that of singleton pregnancies. Bile acid levels can exceed normal values by over tenfold, increasing the risks of preterm delivery, fetal distress, stillbirth, and a higher perinatal mortality rate.

Anemia

The risk of anemia is 2.4 times higher than in singleton pregnancies, often caused by deficiencies in iron and folic acid.

Polyhydramnios

Polyhydramnios occurs in approximately 12% of cases. Acute polyhydramnios, often observed in monochorionic twin pregnancies during mid-gestation, is associated with twin-to-twin transfusion syndrome (TTTS) or fetal malformations.

Preterm Premature Rupture of Membranes (PPROM)

The incidence is about 14%, which may be related to increased intrauterine pressure.

Uterine Atony

Overstretching of the uterine muscle fibers can result in primary uterine atony, leading to prolonged labor.

Placental Abruption

Placental abruption is a leading cause of antepartum hemorrhage in twin pregnancies. This may be related to the higher incidence of hypertensive disorders of pregnancy. Sudden reduction of the uterine cavity volume after the delivery of the first fetus is another common cause.

Postpartum Hemorrhage (PPH)

The average amount of postpartum bleeding in vaginal deliveries involving twin pregnancies is ≥500 mL. This is associated with uterine overdistension leading to uterine atony, as well as the increased surface area of placental attachment.

Miscarriage and Preterm Birth

The risk of miscarriage is two to three times higher than in singleton pregnancies, which may be linked to embryonic abnormalities, placental development issues, placental circulation disorders, limited uterine space, and elevated intrauterine pressure. The risk of preterm delivery in twin pregnancies is approximately seven to ten times greater than in singleton pregnancies. For monochorionic and dichorionic twin pregnancies, the risk of miscarriage between 11 and 24 weeks is approximately 10% and 2%, respectively, while the risk of preterm delivery before 32 weeks is 10% and 5%, respectively.

Umbilical Cord Abnormalities

Monochorionic monoamniotic twin pregnancies are prone to complications such as umbilical cord entanglement or twisting, which can lead to fetal death. Umbilical cord prolapse is another common complication in twin pregnancies, often occurring when the membranes rupture in cases of fetal malpresentation, unengaged presenting parts, or between the delivery of the first and second twins. This is a major cause of acute fetal hypoxia and death.

Locked Twin and Fetal Head Impaction

Locked twin occurs when the first fetus presents as breech and the second as cephalic. During labor, the head of the first fetus becomes locked with the head of the second fetus, causing obstructed labor. Fetal head impaction occurs when both fetuses present cephalically and simultaneously descend into the pelvis, leading to obstructed labor.

Fetal Malformations

The risk of fetal malformations in dizygotic twins is similar to that in singleton pregnancies. However, monozygotic twins have a two- to threefold higher incidence of fetal malformations. Common anomalies include cardiac defects, neural tube defects, facial malformations, gastrointestinal abnormalities, and gastroschisis. Certain defects are unique to monozygotic twins, such as conjoined twins and acardia.

Unique Complications of Monochorionic Twin Pregnancies

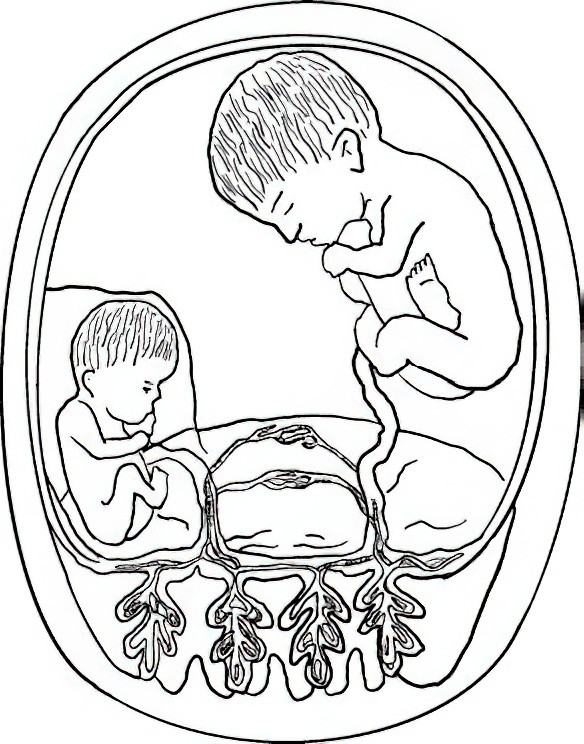

Monochorionic twins share a single placenta, with vascular anastomoses between the fetuses’ circulations, increasing the likelihood of both serious complications and higher perinatal morbidity and mortality rates.

Twin-to-Twin Transfusion Syndrome (TTTS)

TTTS is a severe complication specific to monochorionic diamniotic twins. Blood is shunted unidirectionally from the artery of one twin (the donor) to the vein of the other twin (the recipient) via arteriovenous anastomoses within the placenta. The donor twin develops anemia, hypovolemia, reduced renal perfusion, oligohydramnios, and may die due to malnutrition. The recipient twin experiences hypervolemia, congestive heart failure, fetal hydrops, and polyhydramnios. Diagnostic criteria include: (i) presence of monochorionic twins, and (ii) discordant amniotic fluid volumes, with a maximum vertical pocket (MVP) >8 cm (or >10 cm after 20 weeks) in one twin and <2 cm in the other. TTTS is staged according to the Quintero system:

- Stage I: Amniotic fluid discordance only.

- Stage II: Donor twin’s bladder not visualized on ultrasound.

- Stage III: Abnormal Doppler studies for the umbilical artery, umbilical vein, or ductus venosus.

- Stage IV: Hydrops in either fetus.

- Stage V: Death of one or both fetuses.

Figure 3 Twin-to-twin transfusion syndrome (TTTS)

Without treatment, the fetal mortality rate for TTTS developing before 24 weeks and reaching Stage II or above exceeds 90%.

Selective Intrauterine Growth Restriction (sIUGR)

sIUGR is another severe complication unique to monochorionic twins. It is diagnosed when the estimated weight of one fetus falls below the 10th percentile for gestational age, and there is a 25% or greater weight discordance between the fetuses. Unequal placental sharing, along with marginal or velamentous umbilical cord insertion in the growth-restricted fetus, are the primary causes. sIUGR is classified into three types:

- Type I: Normal umbilical artery blood flow in the smaller fetus.

- Type II: Absent or reversed diastolic flow in the umbilical artery of the smaller fetus.

- Type III: Intermittent changes in umbilical artery diastolic flow in the smaller fetus.

sIUGR can be confused with TTTS during diagnosis, but they differ. Diagnostic criteria for TTTS include amniotic fluid discordance, while sIUGR is identified based on fetal weight discordance and growth restriction without amniotic fluid changes.

Twin Reversed Arterial Perfusion (TRAP) Sequence

Also known as acardiac twin, this rare anomaly occurs in 2.6% of monochorionic pregnancies, equating to approximately 1 in 10,000 pregnancies overall. One twin lacks a functional heart or has an absent heart entirely. Blood supply for the acardiac twin is provided by an arterial-arterial anastomosis from the normal pump twin. Without intervention, the pump twin can experience heart failure and death.

Twin Anemia-Polycythemia Sequence (TAPS)

TAPS represents a chronic form of twin-to-twin transfusion in monochorionic diamniotic twins, characterized by significant hemoglobin differences between the fetuses but without amniotic fluid discordance. Diagnosis relies on measuring the middle cerebral artery peak systolic velocity (MCA-PSV), with anemia defined as MCA-PSV >1.5 multiples of the median (MoM) in the donor twin and <1.0 MoM in the recipient twin. Optimal diagnostic criteria remain under debate.

Monochorionic Monoamniotic Twins (Mo-Mo)

Mo-Mo twins share a single amniotic sac without a separating membrane, leading to increased risks of cord entanglement and knotting that can result in in-utero complications.

Management

Management and Monitoring During Pregnancy

Adequate nutrition is essential, with a focus on consuming foods rich in protein, vitamins, and essential fatty acids. Iron, folic acid, and calcium supplements are particularly important to prevent anemia and hypertensive disorders of pregnancy.

Prevention and management of preterm labor are critical aspects of prenatal care for twin pregnancies. Physical activity should be appropriately reduced. If symptoms of preterm labor occur before 34 weeks of gestation, tocolytic agents may be required. Hospitalization is recommended in the event of uterine contractions or vaginal fluid leakage.

Early diagnosis and treatment of pregnancy complications are important, given that twin pregnancies are associated with an increased risk of conditions such as hypertensive disorders of pregnancy and intrahepatic cholestasis of pregnancy.

Monitoring fetal growth and development, as well as fetal position, is necessary. Termination of pregnancy is considered in cases of fetal malformations, particularly conjoined twins. For dichorionic twin pregnancies, fetal growth should be assessed with ultrasound every four weeks. For monochorionic twin pregnancies, ultrasound evaluation should begin at 16 weeks of gestation and continue every two weeks, with increased frequency as needed in late pregnancy. Follow-up assessments should include fetal growth and development, estimated weight differences, amniotic fluid levels, and Doppler flow studies. Although fetal position abnormalities detected via ultrasound are generally not corrected, determining fetal positions in late pregnancy is useful when planning the mode of delivery.

Time to Delivery

Dichorionic twin pregnancies without complications should ideally continue to 38 weeks, with delivery considered by 39 weeks at the latest. Monochorionic diamniotic twin pregnancies without complications can be managed under close monitoring until delivery at 35–37 weeks. Delivery for monochorionic monoamniotic twin pregnancies is typically planned between 32 and 34 weeks. In complicated twin pregnancies, such as those involving TTTS, sIUGR, or TAPS, individualized delivery plans depend on the maternal and fetal conditions.

Intrapartum Management

For twin pregnancies undergoing planned vaginal delivery, approximately 20% of cases involve a change in the fetal position of the second twin. Therefore, preparations for assisted delivery or cesarean delivery of the second twin are essential. Vaginal delivery is possible when the first twin presents cephalically. However, if the first twin presents cephalically and the second twin does not, there is a higher risk of requiring assisted delivery or cesarean delivery for the second twin. When the first twin presents breech, umbilical cord prolapse is more likely to occur upon rupture of membranes. Additionally, if the second twin presents cephalically, there is a risk of fetal head entrapment or locked twins; therefore, the criteria for cesarean delivery are often expanded.

During labor, the following considerations are important:

- Maternal energy levels must be maintained, with attention given to adequate nutritional intake and rest.

- Continuous monitoring of fetal heart rates is necessary.

- Uterine contractions and labor progression should be closely observed. Artificial rupture of membranes during early labor may be performed in cases with engaged fetal heads to accelerate labor progress. If uterine contractions are inadequate, oxytocin may be administered intravenously under close monitoring to enhance labor.

- Episiotomy, particularly a mediolateral or posterior episiotomy, may be performed during the second stage of labor to reduce pressure on the fetal head.

After delivery of the first twin, the umbilical cord on the placental side must be clamped immediately to prevent blood loss from the second twin. The position of the second twin should be stabilized to a longitudinal lie through abdominal manipulation, and fetal heart rate, uterine contractions, and vaginal bleeding should be carefully monitored. Vaginal examination is advised to assess fetal position, rule out umbilical cord prolapse, and detect placental abruption. In the absence of complications, spontaneous delivery of the second twin typically occurs within 20 minutes. If no uterine contractions occur within 15 minutes, artificial rupture of membranes and intravenous oxytocin may be used to stimulate contractions. Regardless of whether delivery is vaginal or cesarean, active measures to prevent and manage postpartum hemorrhage are necessary.

Management of Monochorionic Twin Pregnancies and Their Unique Complications

The outcome of twin pregnancies depends on chorionicity rather than zygosity. Monochorionic twin pregnancies have higher rates of perinatal complications and mortality. For TTTS diagnosed between 16 and 26 weeks (Quintero stages II–IV and some cases of stage I), fetoscopic laser ablation is the preferred treatment. When TTTS is detected at a later stage and is accompanied by polyhydramnios, rapid amniotic fluid reduction may be performed. In cases of severe sIUGR or monochorionic twin pregnancies with one fetus presenting congenital anomalies or TRAP sequence, selective fetal reduction (using techniques such as radiofrequency ablation or umbilical cord coagulation) may be performed to remove the growth-restricted or malformed fetus.