Viral hepatitis refers to infectious diseases primarily affecting the liver, caused by hepatitis viruses. The causative pathogens include hepatitis A virus (HAV), hepatitis B virus (HBV), hepatitis C virus (HCV), hepatitis D virus (HDV), and hepatitis E virus (HEV). All of these are RNA viruses except for HBV, which is a DNA virus.

Physiological Changes in the Liver During Pregnancy, Delivery, and the Postpartum Period

The liver undergoes structural and functional changes during pregnancy, delivery, and the postpartum period:

- Basal metabolic rate increases during pregnancy, with higher nutrient demands leading to reduced hepatic glycogen storage and decreased glucose tolerance.

- Large amounts of estrogen are metabolized in the liver during pregnancy, which can impair hepatic fat transport and bile excretion, resulting in elevated blood lipid levels.

- The liver is required to metabolize and detoxify fetal metabolic byproducts.

- Labor leads to an increased hepatic burden due to physical exertion, hypoxia, accumulation of acidic metabolic byproducts, and postpartum hemorrhage.

These physiological changes do not increase susceptibility to hepatitis viruses but may accelerate disease progression in individuals with existing hepatitis. Coexisting complications or comorbidities during pregnancy may also lead to liver damage, with clinical presentations potentially overlapping with viral hepatitis, thereby complicating diagnosis and treatment.

Effects on Maternal and Fetal Health

The physiological changes in pregnancy progressively increase hepatic burden as gestation advances, particularly in the second and third trimesters. The risk of developing severe hepatitis increases in this context. Severe hepatitis may result in coagulopathy, with an increased risk of postpartum hemorrhage and, in severe cases, maternal death. Abnormal liver function increases the likelihood of miscarriage, preterm delivery, stillbirth, or neonatal death, with perinatal mortality rates as high as 4.6%. High viral loads during pregnancy and significant viral exposure during delivery increase the risk of vertical transmission. Neonates who do not receive timely vaccination are at greater risk of infection, and given their immature immune function, a significant proportion may become chronic virus carriers after infection.

Vertical Transmission of Hepatitis Viruses

Hepatitis A Virus (HAV)

HAV is transmitted via the digestive tract and does not typically cross the placental barrier to infect the fetus. Vertical transmission is rare but may occur during delivery due to contact with maternal blood, ingestion of amniotic fluid, or contamination with meconium.

Hepatitis B Virus (HBV)

Vertical transmission is the primary cause of chronic HBV infection. More than 80% of neonates or infants infected with HBV develop chronic HBV infection. Although the combined administration of hepatitis B vaccine and hepatitis B immunoglobulin can significantly reduce vertical transmission, there remains a 10%–15% failure rate.

Hepatitis C Virus (HCV)

The rate of vertical transmission for HCV ranges from 4% to 7%, with higher transmission rates correlating with elevated maternal HCV-RNA titers. Of neonates with intrauterine infection, 20%–30% may achieve spontaneous viral clearance within the first year of life.

Hepatitis D Virus (HDV)

HDV depends on HBV for replication and expression, and infection typically co-occurs with HBV. The transmission route is similar to that of HBV.

Hepatitis E Virus (HEV)

There are a few reported cases of vertical transmission. The transmission route is similar to that of HAV.

Diagnosis

Thorough history-taking, clinical evaluation, laboratory tests, and imaging studies are required for a comprehensive diagnosis:

History and Clinical Presentation

A history of close contact with individuals with viral hepatitis or blood product transfusion within the past six months is relevant. The typical incubation periods for hepatitis viruses are:

- HAV: 2–7 weeks,

- HBV: 6–20 months,

- HCV: 2–26 weeks,

- HDV: 4–20 weeks,

- HEV: 2–8 weeks.

Symptoms such as unexplained gastrointestinal discomfort (e.g., loss of appetite, nausea, vomiting, abdominal distention, liver pain) associated with fatigue, chills, fever, jaundice, or dark urine may occur. Physical examination may reveal hepatomegaly and tenderness over the liver area.

Laboratory Tests

These include liver function and virology testing.

Liver Function Tests

Alanine aminotransferase (ALT) is the most sensitive marker of liver cell damage.

Aspartate aminotransferase (AST), bilirubin, and coagulation tests are also evaluated. Total bilirubin levels are more prognostically valuable than ALT or AST. Persistent bilirubin elevation with a decline in transaminase levels ("bilirubin-transaminase dissociation") suggests severe hepatocellular necrosis and poor prognosis in severe hepatitis.

Prothrombin time activity (PTA) serves as a critical indicator of disease severity, with values between 80% and 100% considered normal. A PTA value <40% is an important marker of severe hepatitis.

Virological Tests

HAV

HAV antibodies (HAV-IgM for recent infection, HAV-IgG for convalescence) and HAV-RNA levels are assessed.

HBV

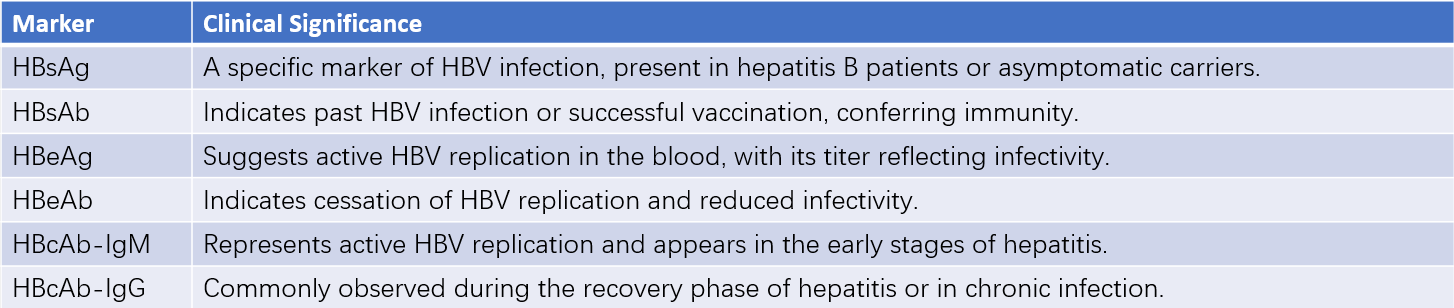

HBV serological markers are evaluated for specific diagnostic significance (refer to clinical guidelines for details).

Table 1 Serological markers of hepatitis B and their clinical significance

Note:

HBsAg: Hepatitis B surface antigen

HBsAb: Hepatitis B surface antibody

HBeAg: Hepatitis B e antigen

HBeAb: Hepatitis B e antibody

HBcAb: Hepatitis B core antibody

IgM: Immunoglobulin M

IgG: Immunoglobulin G

HCV

HCV antibodies suggest past infection, while HCV-RNA indicates active infection.

HDV

Both HDV antibodies and HBV serological markers are tested simultaneously.

HEV

Antibody (anti-HEV-IgM and anti-HEV-IgG) and RNA testing are performed, but HEV antigen tests remain challenging, and antibody detection may be delayed during the acute phase. Negative antibodies do not entirely exclude the diagnosis.

Imaging Studies

Ultrasound is typically used to assess the size of the liver and spleen, as well as the presence of complications such as cirrhosis, ascites, or fatty liver. Magnetic resonance imaging may be conducted if necessary.

Severe Hepatitis During Pregnancy

Severe hepatitis should be considered if any of the following are observed:

- Severe gastrointestinal symptoms,

- Total serum bilirubin >171 μmol/L (10 mg/dL) or a rapid increase of 17.1 μmol/L per day,

- Coagulopathy with a bleeding tendency (PTA <40%),

- Liver shrinkage, hepatic fetor, or significant liver dysfunction,

- Hepatic encephalopathy,

- Hepatorenal syndrome.

- Clinical diagnosis of severe hepatitis is established if three criteria are met:

- Symptoms such as fatigue, loss of appetite, or nausea/vomiting,

- PTA <40%,

- Total serum bilirubin >171 μmol/L.

Differential Diagnosis

Intrahepatic Cholestasis of Pregnancy

This condition is characterized by itching and elevated bile acids in the second and third trimesters of pregnancy. Transaminase levels may be mildly to moderately elevated, while bilirubin levels may be normal or elevated. Serological tests for viral hepatitis are negative. Clinical symptoms and liver function abnormalities typically resolve within a few days to weeks postpartum.

Acute Fatty Liver of Pregnancy (AFLP)

AFLP commonly occurs in late pregnancy, with clinical manifestations resembling severe hepatitis. Key features for differentiation include:

- Hepatitis markers are generally negative in AFLP.

- Transaminase levels are higher in severe hepatitis.

- Urine bilirubin is typically negative in AFLP but positive in severe hepatitis.

- AFLP often stabilizes and improves approximately one week after delivery, whereas the recovery period for severe hepatitis may take several months.

HELLP Syndrome

Occurs in the context of pregnancy-associated hypertensive disorders and is characterized by elevated liver enzymes, intravascular hemolysis, and thrombocytopenia. The condition can improve rapidly after delivery.

Liver Damage Due to Hyperemesis Gravidarum

Severe appetite loss, nausea, and vomiting during early pregnancy may result in mild liver dysfunction. Symptoms improve after electrolyte and acid-base imbalances are corrected, with liver function normalizing. Jaundice is absent, and serological testing for viral hepatitis is negative, aiding in differentiation.

Drug-Induced Liver Injury

A history of using hepatotoxic drugs, such as chlorpromazine, promethazine, barbiturate sedatives, methimazole, isoniazid, or rifampin, can point to drug-induced liver injury. Liver function typically recovers after discontinuing the offending agent.

Management

Pre-Pregnancy Management

Women of childbearing age infected with HBV should undergo liver function tests, HBV-DNA quantification, and liver ultrasound before pregnancy. The optimal time for conception is when liver function is normal, serum HBV-DNA levels are low, and no significant abnormalities are detected on ultrasound. For individuals undergoing antiviral therapy with interferon, pregnancy is advised six months after discontinuation. For those on long-term nucleos(t)ide analog therapy, tenofovir is recommended for preconception planning and can be continued during pregnancy.

Management During Pregnancy

For mild cases of acute hepatitis, individuals who improve with active treatment may continue with the pregnancy. Treatment plans should be formulated in consultation with specialists, with key measures including liver protection, symptomatic treatment, and supportive therapies. Regular monitoring of liver function and coagulation markers is essential during treatment. Pregnant individuals with chronic active hepatitis whose condition worsens and does not respond well to treatment should consider pregnancy termination.

Management During Delivery

Comprehensive evaluations of liver function and coagulation status are essential before delivery, and blood products should be prepared as needed. Continuous monitoring during labor is required, with the avoidance of prolonged labor. Individuals with viral hepatitis during pregnancy are at higher risk of postpartum hemorrhage, necessitating effective preventive and therapeutic strategies.

Postpartum Management

Attention to rest and liver care is needed during the postpartum period. Antibiotics with minimal liver toxicity should be chosen to prevent and treat infections. For HBsAg-positive mothers, regardless of HBeAg status, breastfeeding is permissible if the newborn has received appropriate active and passive immunization, without the need to test breast milk for HBV-DNA. For individuals whose condition does not permit breastfeeding, milk suppression may be achieved with oral malt or external application of sodium sulfate to the breasts, while avoiding estrogen-based medications that could harm the liver.

Management of Severe Hepatitis

Hospital admission and multidisciplinary management are required for individuals with disease progression toward severe hepatitis.

Liver Protection Therapy

The primary goals are to prevent hepatocyte necrosis, promote hepatocyte regeneration, and reduce jaundice. Common treatments include hepatoprotective drugs, hepatocyte membrane stabilizers, detoxifying liver-protective agents, and choleretic medications.

Management of Associated Complications

The management includes:

- Prevention and treatment of hepatic encephalopathy: This involves addressing precipitating factors (e.g., severe infection, bleeding, electrolyte imbalance), maintaining bowel regularity, reducing intestinal absorption of toxic byproducts like ammonia, adjusting nutrient intake as necessary, and use of ammonia-lowering agents or therapies to improve brain function, including artificial liver support systems when required.

- Addressing coagulation abnormalities: Fresh frozen plasma and cryoprecipitate may be used to improve coagulation function.

- Prevention and treatment of hepatorenal syndrome: Maintaining effective circulating blood volume and electrolyte balance is essential, avoiding medications that could harm the liver and kidneys.

- Infection prevention and control: Individuals with severe hepatitis are prone to bile duct, abdominal, and pulmonary infections. Empirical anti-infective treatment may be initiated while awaiting pathogen identification, with adjustments made based on microbiological findings and susceptibility testing results.

Obstetric Management

While stabilizing the condition, pregnancy should be terminated promptly. Cesarean delivery is often preferred. Postpartum hemorrhage risk is high for individuals with severe hepatitis, requiring active prevention and management. In cases of refractory postpartum hemorrhage unresponsive to various treatments, hysterectomy may be indicated.

Prevention of Vertical Transmission of Hepatitis Viruses

Hepatitis A Virus (HAV)

Individuals at risk of HAV infection may receive intramuscular immunoglobulin within seven days of exposure. Newborns at risk of infection may also receive intramuscular immunoglobulin post-delivery to prevent infection. Breastfeeding is contraindicated during the acute phase of HAV infection.

Hepatitis B Virus (HBV)

Measures to prevent vertical transmission of HBV include:

- Prenatal screening of serum HBV markers for all pregnant individuals.

- For those with HBV-DNA levels >2×105 IU/ml in the second or third trimester, tenofovir may be initiated at 28 weeks of gestation, with informed consent, to reduce vertical transmission.

- Elective cesarean delivery is not recommended solely to prevent vertical transmission of HBV.

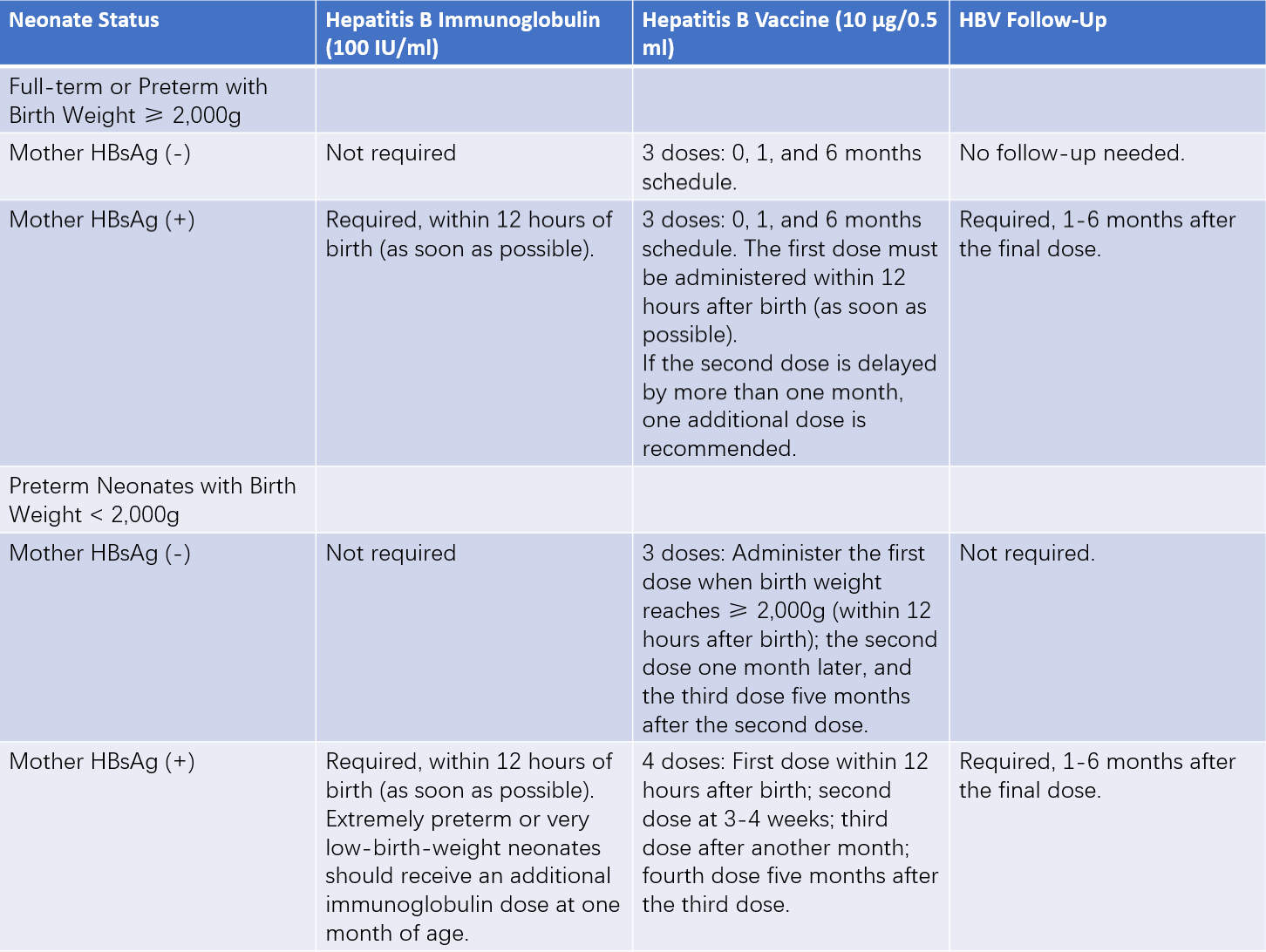

- Newborns require active and passive immunization for mother-to-child transmission prevention.

Table 2 HBV mother-to-child transmission prevention strategy for neonates

Notes:

1, If maternal HBsAg status is unknown, the neonate should be managed as if the mother is HBsAg-positive, particularly in cases where there is a family history of hepatitis B.

2, For HBsAg-negative mothers with neonates weighing less than 2,000g, the first hepatitis B vaccine dose should be delayed until the neonate reaches a weight of 2,000g. If discharge occurs before reaching this weight, the first vaccine dose should be administered before discharge. For neonates born to HBsAg-positive mothers, vaccination should proceed as soon as the neonate is stable, regardless of weight.

3, For neonates born to HBsAg-positive mothers, regardless of prematurity or medical condition (including cases requiring resuscitation), administration of a single dose of hepatitis B immunoglobulin should occur within 12 hours after birth, completed as quickly as possible, preferably within minutes.

4, For neonates born to HBsAg-positive mothers, the first dose of the hepatitis B vaccine should be administered as soon as the neonate is stable, regardless of prematurity or birth weight. If the neonate requires resuscitation or is in critical condition, vaccination may be delayed until one week after stabilization.

Hepatitis C Virus (HCV)

No specific immunization methods exist. Reducing iatrogenic transmission remains key to prevention. Passive immunization with immunoglobulin may be considered for at-risk populations.