Ectopic pregnancy refers to the implantation of a fertilized egg outside the uterine cavity, commonly referred to as extrauterine pregnancy. The most frequent type of ectopic pregnancy is tubal pregnancy, accounting for approximately 95% of cases. Less common types include ovarian pregnancy, abdominal pregnancy, cervical pregnancy, and pregnancy within the broad ligament. Additionally, certain rare forms of ectopic pregnancy include pregnancy in a rudimentary uterine horn, cesarean scar pregnancy, and combined intrauterine and extrauterine pregnancy. Ectopic pregnancy is a common cause of acute abdominal emergencies in obstetrics and gynecology, with an incidence of 2–3%. It remains the leading cause of maternal death during early pregnancy. Advancements in early diagnosis and management have significantly improved patient survival rates and the ability to preserve fertility.

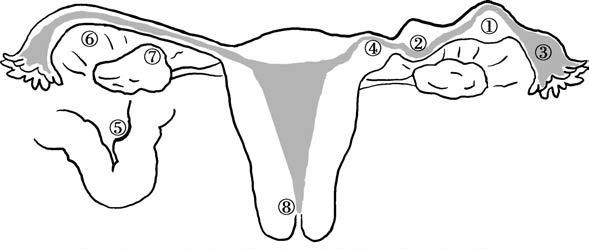

Figure 1 Locations of ectopic pregnancy

1, Ampullary pregnancy of the fallopian tube

2, Isthmic pregnancy of the fallopian tube

3, Fimbrial pregnancy of the fallopian tube

4, Interstitial pregnancy of the fallopian tube

5, Abdominal pregnancy

6, Broad ligament pregnancy

7, Ovarian pregnancy

8, Cervical pregnancy

Tubal Pregnancy

Tubal pregnancy is the most common form of ectopic pregnancy, with implantation most frequently occurring in the ampullary segment of the fallopian tube (approximately 78%). Other sites include the isthmus and fimbrial segments, with the interstitial segment being less common. Rarely, tubal pregnancies may present as ipsilateral or bilateral multiple pregnancies, or as concurrent intrauterine and extrauterine pregnancies, particularly in individuals using assisted reproductive technologies or ovulation induction methods.

Etiology

Tubal Inflammation

Tubal inflammation is the primary cause of tubal pregnancy and can be classified as tubal mucosal inflammation or peritubal inflammation.

- Mild tubal mucosal inflammation may cause adhesions in the mucosal folds, narrowing of the lumen, or impairment of ciliary function, leading to disruption of the transport of the fertilized egg and its eventual implantation within the fallopian tube.

- Peritubal inflammation primarily affects the serosal or muscular layers, often resulting in peritubal adhesions, torsion, luminal narrowing, and reduced peristalsis, which interferes with the passage of the fertilized egg.

- Neisseria gonorrhoeae and Chlamydia trachomatis-induced salpingitis often involves the mucosa, whereas infections following abortion or childbirth typically involve the serosa, contributing to peritubal inflammation.

- Nodular salpingitis isthmica nodosa, a specific form of tubal inflammation, often results from infection with Mycobacterium tuberculosis. In this condition, the tubal mucosal epithelium forms diverticulum-like extensions into the muscular layer, causing nodular hypertrophy of the proximal muscular layer. This impairs tubal peristalsis and increases the risk of tubal pregnancy.

History of Tubal Pregnancy or Surgery

A history of prior tubal pregnancy increases the risk of recurrence to approximately 10% after one episode and over 25% after two or more episodes. The likelihood of tubal pregnancy is elevated following tubal reconstructive surgery and depends on the functionality and condition of the tubal structure, type of surgery, and surgical expertise. The risk of tubal pregnancy is 5–19 times higher among individuals who experience sterilization failure.

Tubal Maldevelopment or Dysfunction

Tubal abnormalities, such as elongated fallopian tubes, underdeveloped muscular layers, absence of ciliated mucosa, dual fallopian tubes, tubal diverticula, or the presence of accessory fimbriae, are all contributing factors to tubal pregnancy. Tubal functions, including peristalsis, ciliary activity, and epithelial secretions, are regulated by estrogen and progesterone. Dysregulation negatively impacts the transport of the fertilized egg. Psychological factors may also induce tubal spasm or abnormal peristalsis, disrupting egg transport and leading to tubal pregnancy.

Assisted Reproductive Technologies (ART)

The use of assisted reproductive technologies has contributed to an increase in the incidence of tubal pregnancy and other less commonly observed types of ectopic pregnancy, such as ovarian, cervical, and abdominal pregnancies.

Contraceptive Failure

The risk of ectopic pregnancy increases following failure of contraceptive methods, including intrauterine device (IUD) failure or emergency contraceptive failure.

Other Factors

Factors such as uterine fibroids or ovarian tumors that compress the fallopian tube may obstruct the lumen, inhibiting the transport of the fertilized egg and increasing the risk of tubal pregnancy. Endometriotic lesions involving the fallopian tube may also elevate the likelihood of tubal implantation of the fertilized egg.

Pathology

Characteristics of the Fallopian Tube

The fallopian tube is characterized by its narrow lumen, thin walls, and lack of submucosal tissue. The fertilized egg rapidly penetrates the mucosal epithelium, reaching or entering the muscular layer. As a result, the development of the fertilized egg or embryo is often abnormal, leading to the following outcomes:

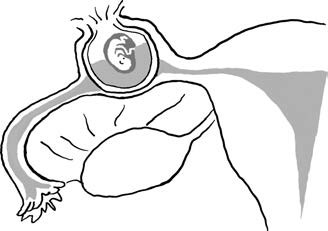

Rupture of Tubal Pregnancy

This is commonly observed around the 6th week of pregnancy, particularly in cases of isthmic tubal pregnancy. The fertilized egg implants between the mucosal folds of the fallopian tube, and as the blastocyst grows, the chorionic villi invade the muscular and serosal layers, eventually breaching the serosa, leading to tubal pregnancy rupture. Given the vascularity of the tubal musculature, rupture often causes a significant amount of intraperitoneal bleeding over a short period, potentially resulting in shock. The volume of bleeding in ruptured tubal pregnancy is typically greater than in tubal abortion, and the associated abdominal pain is severe. Bleeding can also occur intermittently, forming clots within the pelvic and abdominal cavities. The gestational sac may pass into the pelvic cavity through the rupture site. The vast majority of tubal pregnancy ruptures are spontaneous, although they may also occur post-coitus or after a bimanual pelvic examination.

Figure 2 Illustration of fallopian tube rupture in tubal pregnancy

Interstitial tubal pregnancy, though less common, is particularly serious due to the thicker muscular layer and rich vascular supply surrounding the interstitial segment of the fallopian tube. Rupture typically occurs between the 12th and 16th weeks of pregnancy and closely resembles uterine rupture, often resulting in hypovolemic shock within a short time frame. Differentiation is necessary between interstitial tubal pregnancy and cornual pregnancy. In cornual pregnancy, the gestational sac implants at the uterotubal junction within the medial portion of the uterine cornua and is continuous with the uterine cavity, whereas interstitial tubal pregnancy involves implantation at the uterotubal junction lateral to the round ligament and is not continuous with the uterine cavity.

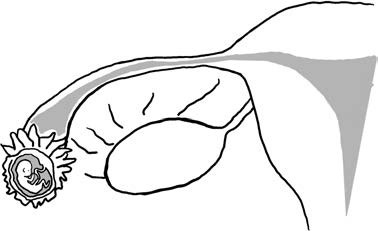

Tubal Abortion

Tubal abortion is commonly seen between the 8th and 12th weeks of pregnancy, particularly in ampullary or fimbrial tubal pregnancies. The fertilized egg implants within the mucosal folds of the fallopian tube, but due to incomplete formation of the decidua, the developing blastocyst frequently projects into the tubal lumen and ultimately causes rupture and bleeding. Separation of the blastocyst from the tubal wall occurs, and if the entire blastocyst detaches and moves into the lumen, reverse peristalsis expels it through the fimbrial end into the abdominal cavity, resulting in a complete tubal abortion. In these cases, bleeding is usually minimal.

Figure 3 Illustration of tubal pregnancy abortion

Incomplete detachment of the blastocyst results in partial expulsion of pregnancy tissue into the abdominal cavity, with some tissue still remaining attached to the tubal wall. This creates an incomplete tubal abortion with continued trophoblastic invasion of the tubal wall, leading to recurrent bleeding. The volume and duration of bleeding depend on the amount of trophoblastic tissue retained in the tubal wall. If the fimbrial end is obstructed and blood cannot flow into the pelvic cavity, the blood accumulates within the tube, forming a hematosalpinx or peritubal hematoma. Persistent bleeding that collects in the rectouterine pouch may form pelvic hematocele or hematoma, occasionally extending into the abdominal cavity. Severe cases can result in hypovolemic shock.

Cessation of Embryonic Development and Absorption

Embryonic growth may cease, with subsequent resorption in a tubal pregnancy. This condition often goes unnoticed clinically and is diagnosed through detection of low levels of human chorionic gonadotropin (hCG). Low hCG levels may lead to a diagnosis of pregnancy of unknown location (PUL), which can be challenging to distinguish from biochemical pregnancy.

Chronic Ectopic Pregnancy

Chronic ectopic pregnancy arises when repeated internal bleeding from tubal rupture or abortion leads to the formation of a pelvic hematoma that fails to resolve over time. The hematoma undergoes organization, hardening, and adhesion to surrounding tissues. In some cases, calcification occurs, forming a lithopedion (stone baby). Organized masses from chronic ectopic pregnancies can persist for years.

Secondary Abdominal Pregnancy

In cases of tubal rupture or tubal abortion, the embryo may be expelled into the abdominal cavity or the broad ligament. Most embryos die in these situations, but rarely they may survive. If the surviving embryo attaches to an original site or re-implants within the abdominal cavity and obtains nutrients, it may continue to grow, resulting in a secondary abdominal pregnancy.

Uterine Changes

Similar to normal pregnancy, in tubal pregnancy, syncytiotrophoblast cells produce hCG, which supports the corpus luteum and increases steroid hormone secretion. This leads to the cessation of menstruation, uterine enlargement, and softening, as well as the development of a decidual reaction in the endometrium.

If the embryo is abnormal or dies, the activity of trophoblast cells diminishes, and the decidua detaches from the uterine wall, resulting in vaginal bleeding. On occasion, the decidua may detach completely and be expelled as a triangular decidual cast; in other cases, it is expelled as fragments. The expelled tissue lacks chorionic villi, and histological examination reveals no trophoblast cells, with a concurrent decline in blood hCG levels.

Endometrial morphology varies under these circumstances. If the embryo has been deceased for an extended period, the endometrium may revert to a proliferative phase. Occasionally, Arias-Stella (A-S) reactions may be observed under microscopic examination. This involves the hyperplasia and hypertrophy of glandular epithelial cells, loss of polarity, large and deeply stained nuclei, cytoplasmic vacuolation, and glandular outgrowth into the lumen in a papillary configuration. This excessive endometrial proliferation is thought to result from prolonged steroid hormone stimulation. If some chorionic villi deeply implanted in the muscular layer remain alive after embryonic death, delayed regression of the corpus luteum may occur, and the endometrium may continue to exhibit secretory phase changes.

Clinical Manifestations

The clinical presentation of tubal pregnancy is associated with the implantation site of the fertilized ovum, whether rupture or abortion occurs, and the volume and duration of bleeding. In early-stage tubal pregnancy, if no abortion or rupture has occurred, symptoms are often non-specific and resemble those of early pregnancy or threatened abortion.

Symptoms

The typical symptoms include amenorrhea, abdominal pain, and vaginal bleeding—collectively referred to as the classic triad of ectopic pregnancy.

Amenorrhea

Most patients report 6 to 8 weeks of missed menstruation. However, in interstitial tubal pregnancy, the duration of amenorrhea tends to be longer. About 20%–30% of patients do not report amenorrhea, often mistaking the irregular vaginal bleeding of ectopic pregnancy for menstruation or dismissing delayed menstruation of only a few days as unremarkable.

Abdominal Pain

Present in 95% of cases, it is the primary symptom. Before rupture or abortion, pain is often experienced as dull or aching in the lower abdomen on one side, resulting from gradual enlargement of the embryo within the tube. In cases of rupture or abortion, there is sudden tearing pain in the lower abdomen on one side, frequently accompanied by nausea and vomiting. If the bleeding remains localized, pain is limited to the lower abdomen. When blood accumulates in the rectouterine pouch, a sensation of rectal fullness may occur. As blood disperses from the lower abdomen to the upper abdomen, pain may radiate throughout the abdomen. Diaphragmatic irritation by blood may result in referred shoulder or chest pain.

Vaginal Bleeding

This is seen in 60%–80% of cases. After embryonic demise, irregular vaginal bleeding is usually dark red or brown, scant, and spotty, generally not exceeding the amount seen with menstruation. A minority of patients may have heavier bleeding, resembling menstrual flow. Vaginal discharge may contain decidual casts or fragments due to detachment of decidua from the uterus. Vaginal bleeding often ceases only after the ectopic tissue is resolved or trophoblastic cells are completely necrotized and absorbed.

Syncope and Shock

Fainting or hemorrhagic shock may occur due to intraperitoneal bleeding and severe abdominal pain. The greater and faster the blood loss, the more rapid and severe the symptoms. However, the severity of symptoms is not necessarily proportional to the amount of vaginal bleeding.

Abdominal Mass

If hematoma persists for a long period after tubal pregnancy rupture or abortion, blood clots may adhere to surrounding structures (such as the uterus, fallopian tubes, ovaries, intestines, or omentum), forming a mass. When the mass is large or located higher, it may be palpable through the abdominal wall.

Signs

General Condition

When intra-abdominal bleeding is limited, compensatory elevation in blood pressure may occur. With more extensive bleeding, signs such as pallor, rapid and thready pulse, tachycardia, and hypotension may be present, indicative of shock. Body temperature is usually normal but may be slightly low during shock. A slight increase in temperature, not exceeding 38°C, may be observed as intraperitoneal blood is absorbed.

Abdominal Examination

There is marked tenderness and rebound tenderness in the lower abdomen, more pronounced on the affected side, while muscular guarding tends to be mild. If there is significant bleeding, shifting dullness may be detected upon percussion. In some cases, a mass may be palpable in the lower abdomen; with recurrent bleeding and accumulation, the mass may enlarge and become firmer.

Gynecological Examination

A small amount of blood is often seen in the vaginal canal, originating from the uterine cavity. In unruptured or non-aborted tubal pregnancies, aside from a slightly enlarged and softened uterus, careful examination may detect an enlarged and tender fallopian tube. In cases of tubal pregnancy rupture or abortion, fullness and tenderness of the posterior vaginal fornix may be found. Elevation or lateral movement of the cervix elicits severe pain—referred to as cervical motion tenderness—one of the main clinical signs of tubal pregnancy, due to increased peritoneal irritation. With significant intra-abdominal bleeding, the uterus may feel mobile. A mass may be palpated on one side or behind the uterus, with variable size, shape, texture, and indistinct borders; tenderness is usually marked. If the condition persists, the mass may become firm and well-demarcated due to organization. In interstitial tubal pregnancy, uterine size generally corresponds with the duration of amenorrhea, but asymmetry is present, with one uterine cornua protruding. The signs of rupture closely resemble those of uterine rupture.

Diagnosis

Clinical manifestations of tubal pregnancy are not obvious when abortion or rupture has not occurred, making diagnosis challenging. Diagnosis often requires the use of auxiliary investigations. With the widespread use of blood hCG testing and transvaginal ultrasound, many tubal pregnancies can now be diagnosed early, prior to abortion or rupture.

Diagnosis is usually not difficult after tubal abortion or rupture. If the diagnosis is unclear, close observation of symptom progression may provide clarity. Persistent vaginal bleeding, worsening abdominal pain, enlargement of pelvic masses, or a declining trend in hemoglobin levels may aid in confirming the diagnosis. The following diagnostic methods can be utilized to assist with diagnosis:

Ultrasound Examination

Ultrasound examination is essential for the diagnosis of ectopic pregnancy and can help determine the location and size of the pregnancy. Transvaginal ultrasound is more accurate than transabdominal ultrasound and is the preferred diagnostic method for suspected ectopic pregnancies.

Sonographic characteristics of ectopic pregnancy include the absence of a gestational sac in the uterine cavity. If an abnormal low-echo region is detected in the adnexal area and a yolk sac, embryo, or primitive fetal heartbeat is observed, ectopic pregnancy can be confirmed. If a mixed echogenic mass is detected in the adnexal area and free-fluid zones are observed in the rectouterine pouch but no embryo or fetal heartbeat is visible, ectopic pregnancy should still be highly suspected. Even if no abnormal echoes are detected outside the uterus, ectopic pregnancy cannot be ruled out. A pseudo-gestational sac (caused by decidual casts or blood) may occasionally be observed within the uterine cavity, necessitating differentiation to avoid misdiagnosis as an intrauterine pregnancy. Additionally, fluid accumulation in the rectouterine pouch alone does not confirm ectopic pregnancy. Combining ultrasound findings with hCG measurements can significantly improve diagnostic accuracy.

hCG Measurement

Urine or blood hCG testing is critical for the early diagnosis of ectopic pregnancy. hCG levels in ectopic pregnancy cases are lower than those in intrauterine pregnancy, but more than 99% of patients with ectopic pregnancies have positive hCG results, except for rare cases of old ectopic pregnancy where results may be negative. If blood hCG is positive, transvaginal ultrasound can confirm the pregnancy location by detecting a gestational sac, yolk sac, or embryo. If no sac or embryo is found in either the uterine or adnexal region, the condition is classified as a pregnancy of unknown location (PUL), raising suspicion for ectopic pregnancy. Serum hCG levels can help further evaluate PUL cases. hCG levels equal to or exceeding 3,500 IU/L should prompt suspicion of ectopic pregnancy, while levels below 3,500 IU/L require monitoring of hCG trends. Persistently rising hCG levels may warrant repeat transvaginal ultrasound to determine the pregnancy location. When hCG fails to rise or rises only slowly, curettage can be performed for pathological examination of the endometrium.

Serum Progesterone Measurement

Serum progesterone measurement has limited predictive value for the diagnosis of ectopic pregnancy.

Laparoscopy

Laparoscopy is no longer the "gold standard" for diagnosing ectopic pregnancy, as 3–4% of cases may be missed due to small gestational sacs, and tubal dilation or color changes may lead to false-positive diagnoses. Laparoscopy is now rarely used as a diagnostic tool and is more commonly employed as a surgical treatment method.

Culdocentesis

Culdocentesis is a simple and reliable diagnostic method for suspected intraperitoneal bleeding. Blood tends to accumulate in the rectouterine pouch, even when bleeding is minimal. Culdocentesis may reveal dark, non-coagulating blood, indicating hemoperitoneum. If the needle inadvertently enters a vein, brighter blood that coagulates within approximately 10 minutes will be observed. Failure to aspirate blood does not rule out ectopic pregnancy, as minimal bleeding, higher-positioned hematomas, or adhesions in the rectouterine pouch may prevent the collection of blood. Negative culdocentesis results, therefore, do not exclude ectopic pregnancy. Abdominal puncture may be considered in cases of pronounced intraperitoneal bleeding or positive shifting dullness.

Diagnostic Curettage

This method is rarely performed and is primarily used for differential diagnosis in cases where the pregnancy location is uncertain or to distinguish between non-viable intrauterine pregnancy and ectopic pregnancy. Pathological examination of uterine contents can confirm intrauterine pregnancy by detecting chorionic villi. The absence of villi and the presence of decidual tissue alone suggest ectopic pregnancy.

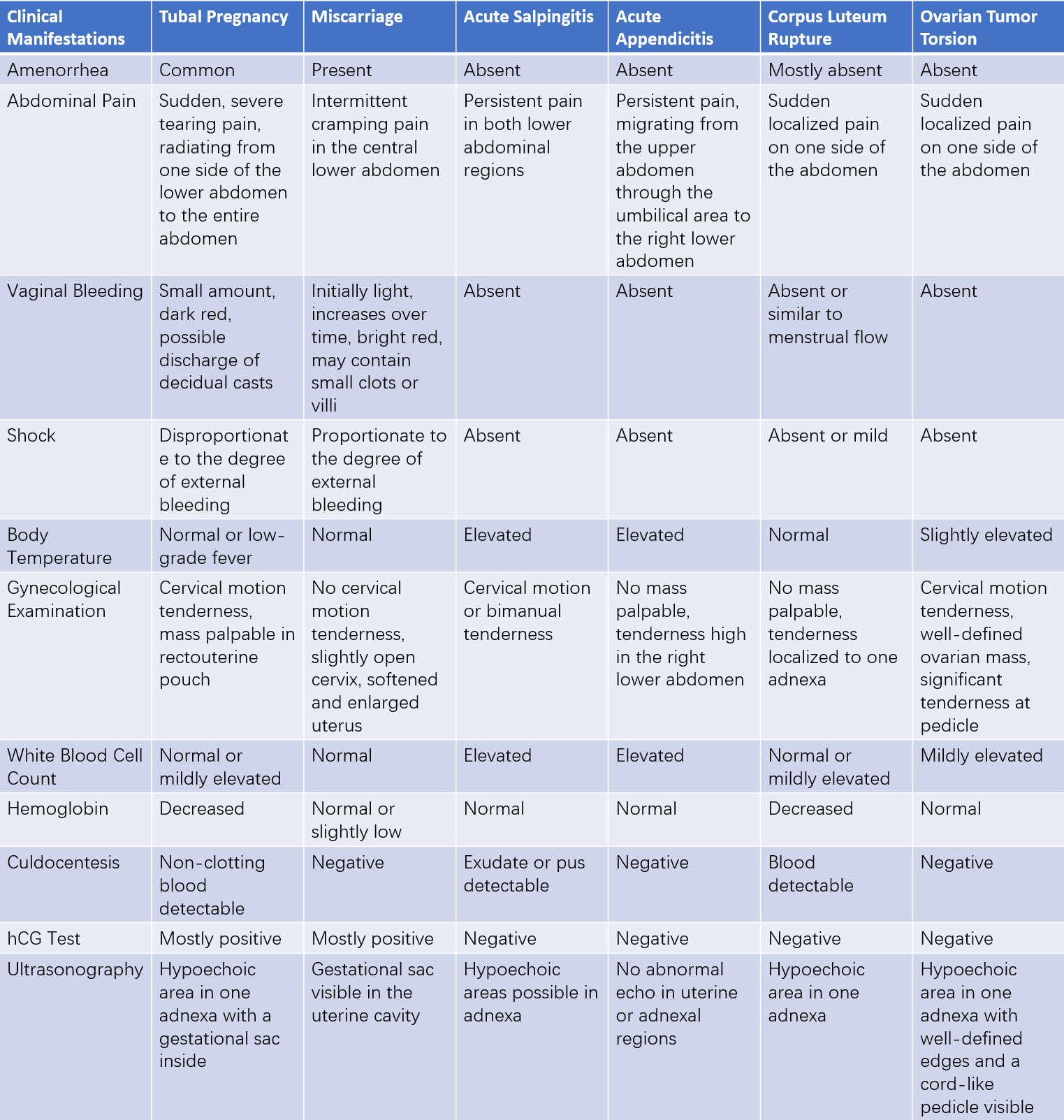

Differential Diagnosis

Tubal pregnancy must be differentiated from spontaneous abortion, acute salpingitis, acute appendicitis, corpus luteum rupture, and torsion of ovarian tumor pedicles.

Table 1 Differential diagnosis of ectopic pregnancy

Treatment

The treatment of tubal pregnancy includes surgical treatment, medical therapy, and expectant management.

Surgical Treatment

Surgical treatment is divided into conservative surgery and radical surgery, depending on whether the affected fallopian tube is preserved. This approach is suitable for patients who meet the following criteria:

- Unstable vital signs or signs of intraperitoneal bleeding.

- Progression of ectopic pregnancy (e.g., serum hCG > 3,000 IU/L, persistent elevation of hCG, presence of fetal cardiac activity, or a large adnexal mass).

- Unreliable follow-up or monitoring.

- Contraindications to or failure of medical therapy.

- Persistent ectopic pregnancy.

Conservative Surgery

Conservative surgery is recommended for young women who wish to preserve fertility, particularly if the contralateral fallopian tube has been removed or is significantly diseased. With advancements in early diagnosis, an increasing number of tubal pregnancies are being identified before rupture or abortion, resulting in a rise in conservative surgical interventions.

Depending on the implantation site and condition of the affected fallopian tube, different surgical techniques are used:

- Fimbrial Pregnancy: The gestational products may be expelled through milking of the fallopian tube.

- Ampullary Pregnancy: Salpingostomy, involving the removal of the embryo through an incision in the tube followed by repair, is performed.

- Isthmic Pregnancy: Resection of the affected segment and end-to-end anastomosis is performed.

Following conservative surgery for tubal pregnancy, there is a risk of persistent ectopic pregnancy, characterized by continued growth of residual trophoblastic tissue, which may cause recurrent bleeding, abdominal pain, and related symptoms. The incidence of persistent ectopic pregnancy ranges from 3.9% to 11.0%. Postoperative monitoring of serum hCG levels is necessary, with weekly follow-up until levels normalize. Persistent ectopic pregnancy can be diagnosed if serum hCG fails to decline, increases after surgery, or does not drop to less than 50% of preoperative levels by day 1 post-surgery or less than 10% by day 12 post-surgery. Persistent ectopic pregnancy can be treated with methotrexate (MTX), with additional surgery as needed. Factors related to the development of persistent ectopic pregnancy include high preoperative serum hCG levels, rapid increases in hCG, or large fallopian tube masses.

Radical Surgery

This approach is recommended for patients with no fertility requirements or in emergency cases such as intra-abdominal bleeding with shock. Current evidence-based guidelines support salpingectomy (removal of the affected fallopian tube) when the contralateral fallopian tube is normal. In severe cases, following stabilization for shock, the affected tube is removed, and the contralateral tube is evaluated as needed.

For interstitial pregnancies, surgical intervention is recommended before rupture to prevent potentially life-threatening heavy bleeding. The procedure typically involves cornual wedge resection and removal of the affected fallopian tube, with or without hysterectomy. In cases where patients desire to preserve fertility, embryo removal through a limited incision may be performed when the clinical condition allows.

Tubal pregnancy surgeries are typically performed laparoscopically unless unstable vital signs necessitate rapid access to control bleeding and complete the procedure. Laparoscopic surgery offers advantages such as shorter hospital stays and quicker postoperative recovery.

Medical Therapy

Medical therapy is primarily used for stable tubal pregnancies as well as for cases of persistent ectopic pregnancy following conservative surgery. This approach is appropriate for confirmed ectopic pregnancies after excluding intrauterine pregnancy. Candidate criteria include:

- No contraindications to medical therapy.

- No rupture of the ectopic pregnancy.

- Adnexal mass diameter less than 4 cm.

- Low serum hCG levels (< 5,000 IU/L).

- No significant intraperitoneal bleeding.

Major contraindications include unstable vital signs, ruptured ectopic pregnancy, adnexal mass diameter ≥ 4.0 cm (or ≥ 3.5 cm with fetal cardiac activity), drug allergies, chronic liver disease, blood disorders, active pulmonary disease, immunodeficiencies, or peptic ulcers.

Methotrexate (MTX) is commonly used, with a mechanism involving the inhibition of trophoblastic cell proliferation and destruction of villi, leading to embryonic necrosis, resorption, and expulsion. Routes of administration include systemic treatment via injection and local application to the gestational sac under ultrasound or laparoscopic guidance.

Systemic treatment protocols include single-dose, two-dose, and multi-dose regimens, although no consensus exists on the optimal protocol. The single-dose regimen typically involves intramuscular injection of 50 mg/m2 MTX.

During MTX treatment, close monitoring with ultrasound and hCG testing is essential, along with attention to clinical progression and potential toxic side effects. Therapeutic success is indicated by a 14-day hCG decrease to below detectable limits after three consecutive negative tests, resolution or significant improvement of abdominal pain, and cessation or reduction of vaginal bleeding. Failure to respond to MTX or the occurrence of acute abdominal symptoms such as rupture requires immediate surgical intervention.

Expectant Management

Expectant management is suitable for patients with stable clinical conditions and no significant or only mild abdominal pain. Ultrasound findings include the absence of significant intraperitoneal bleeding, an adnexal mass with a mean diameter not exceeding 3.0 cm, and no fetal cardiac activity. Serum hCG levels should be less than 2,000 IU/L and demonstrate a downward trend. During expectant management, close surveillance with ultrasound and hCG testing is necessary, with careful attention to clinical progression.

Other Forms of Pregnancy

Ovarian Pregnancy

Ovarian pregnancy refers to the implantation and development of a fertilized egg within the ovary. Its incidence is approximately 1 in 7,000–50,000 pregnancies. Diagnostic criteria for ovarian pregnancy include:

- Intact fallopian tube.

- Ectopic pregnancy located within the ovarian tissue.

- Ectopic pregnancy connected to the uterus via the ovarian ligament.

- Ovarian tissue present on the wall of the gestational sac.

The clinical features of ovarian pregnancy are similar to those of tubal pregnancy, with common symptoms including amenorrhea, abdominal pain, and vaginal bleeding. Most ovarian pregnancies rupture in the early stages; however, rare cases have been reported where pregnancy progresses to full term, occasionally resulting in fetal survival. Rupture can lead to massive intraperitoneal hemorrhage and even shock. Consequently, ovarian pregnancy is often preoperatively diagnosed as tubal pregnancy or misdiagnosed as corpus luteum rupture. Definitive diagnosis typically occurs intraoperatively following careful exploration, and excised tissues must undergo routine pathological examination for confirmation.

Treatment mainly involves surgical intervention, with procedures tailored to the extent of the lesion. Appropriate methods include partial ovarian resection, wedge resection, total ovarian resection, or removal of adnexa on the affected side.

Abdominal Pregnancy

Abdominal pregnancy refers to a pregnancy wherein the embryo or fetus develops within the abdominal cavity, outside the fallopian tubes, ovaries, or broad ligaments. Its incidence is approximately 1 in 10,000–25,000 pregnancies, with a maternal mortality rate of about 5% and fetal survival rate as low as 1 per 1,000. Abdominal pregnancies are classified as primary or secondary:

- Primary Abdominal Pregnancy occurs when the fertilized egg directly implants on structures such as the peritoneum, mesentery, or omentum. These cases are extremely rare.

- Secondary Abdominal Pregnancy commonly results from tubal pregnancy rupture or abortion, but may occasionally follow ovarian pregnancy or uterine pregnancy when uterine defects are present, such as rupture of a scarred uterus or uterine peritoneal fistula.

Patients often present with amenorrhea and early pregnancy symptoms, typically accompanied by a history of symptoms associated with tubal pregnancy abortion or rupture, including abdominal pain and vaginal bleeding, which may gradually resolve. Over time, abdominal enlargement is observed, and fetal movements may cause abdominal pain. Physical examination often reveals unclear uterine contours, easy palpation of fetal limbs, abnormal fetal positions, high-floating presentation, and distinctly audible fetal heart tones. Gynecological examination typically notes upward displacement of the cervix, uterine size smaller than expected for the gestational age and shifted to one side, while the fetus is located on the opposite side. As the pregnancy nears term, false labor-like contractions may occur; however, the cervical os does not dilate, and fetal presentation cannot be palpated through the cervix.

Ultrasound imaging may reveal an empty uterine cavity, separation of the fetus from the uterus, absence of uterine muscle layer between the fetus and bladder, abnormal fetal position or uterine anomalies, and placental tissue located outside the uterus. Magnetic resonance imaging (MRI) and computed tomography (CT) may further assist in diagnosis.

Once abdominal pregnancy is confirmed, cesarean section is performed to extract the fetus. Placental management depends on the site of attachment and the duration since fetal demise or survival. If the placenta is attached to the uterus, fallopian tubes, or broad ligament, the placenta and associated organs may be removed together. When placental attachment is to the peritoneum or mesentery and the fetus is viable or recently deceased (within 4 weeks), the placenta is typically left in situ, with the umbilical cord ligated close to the placenta. Absorption of the retained placenta usually occurs over approximately six months; however, if infection arises or absorption fails, reoperation may be necessary for removal or drainage. If fetal demise occurred long ago, attempts can be made to remove the placenta, though difficulties may necessitate leaving the placenta in situ. Routine administration of antibiotics is required postoperatively to prevent infection. For retained placentas, follow-up using ultrasound and blood hCG monitoring is performed to assess placental regression and absorption.

Cervical Pregnancy

Cervical pregnancy refers to implantation and development of a fertilized egg within the cervical canal. This condition is extremely rare, with an incidence of approximately 1 in 8,600–12,400 pregnancies. Recent increases in the use of assisted reproductive technologies have led to higher rates of cervical pregnancy. It is more commonly observed in multiparous women and is characterized by amenorrhea and early pregnancy symptoms. Due to the implantation within the fibrous tissues of the cervix, pregnancy generally does not progress beyond 20 weeks. The primary symptoms include painless vaginal bleeding or blood-tinged discharge, typically starting as minor spotting and progressively increasing; intermittent massive vaginal bleeding may also occur.

Examination reveals a significantly enlarged, barrel-shaped cervix that appears softened and bluish in color. The external cervical os is dilated with thin margins, while the internal os remains closed. The body of the uterus is normal-sized or slightly enlarged. Ultrasound diagnostic criteria for cervical pregnancy include cervical canal dilation, visualization of a gestational sac or placenta within the canal (often showing fetal heart activity or blood flow signals), absence of intrauterine pregnancy, and observable uterine endometrial lines. Dynamic ultrasound imaging of persistent cervical-specific changes facilitates diagnosis and differentiation from inevitable miscarriage.

Surgical treatment consists of cervical curettage or suction curettage. Preoperative measures include local injection of vasopressin into the cervix or vaginal ligation of cervical branches of the uterine artery to reduce bleeding risk. Blood transfusion preparations should be made before surgery, and uterine artery embolization may be performed to prevent or minimize intraoperative bleeding. In cases of uncontrolled bleeding, cervical wound tamponade with gauze or balloon compression may be applied. Rare circumstances necessitate bilateral internal iliac artery ligation or even hysterectomy to preserve life.

Patients with hemodynamically stable cervical pregnancies may undergo preoperative treatment with MTX. Treatment options include MTX intramuscular injection of 20 mg daily for 5 days, single-dose intramuscular injection of 50 mg/m2 MTX, or direct injection of 50 mg MTX into the gestational sac. If fetal heart activity is present, 2 ml of 10% potassium chloride (KCl) may first be injected into the gestational sac. Following MTX treatment, embryonic death occurs, leading to necrosis of surrounding villous tissue and significantly reducing bleeding during subsequent curettage.