Gestational age is calculated from the first day of the last menstrual period, typically two weeks earlier than the time of ovulation or fertilization and three weeks earlier than implantation. Pregnancy lasts approximately 280 days, or 40 weeks. During the first 10 weeks of gestation (8 weeks post-fertilization), the embryo undergoes organ differentiation and formation. From the 11th week of gestation (9 weeks post-fertilization), the term fetus is used, marking a period when organ systems continue to grow and gradually mature.

Features of Embryo and Fetal Development

Embryo and fetal development can be described based on gestational age, grouped into 4-week (1-month) intervals.

- End of 4 weeks: The embryonic disc and body stalk become identifiable.

- End of 8 weeks: The embryo begins to resemble a human form, with a disproportionately large head comprising nearly half of the total body size. Features such as the eyes, ears, nose, mouth, fingers, and toes become distinguishable. Organs are differentiating and developing, and the heart has formed.

- End of 12 weeks: The fetus is approximately 9 cm in overall length and 6–7 cm in crown-rump length. The external genitalia exhibit initial development, allowing early differentiation of sex. Limb movement is detectable.

- End of 16 weeks: The fetus is about 16 cm in overall length and 12 cm in crown-rump length, weighing approximately 110 g. The sex of the fetus can be confirmed based on external genitalia. Hair begins to grow on the scalp, and initial respiratory movements occur. The skin is thin, dark red, and lacks subcutaneous fat. Some pregnant women may begin to perceive fetal movements.

- End of 20 weeks: The fetus is approximately 25 cm in overall length, 16 cm in crown-rump length, and weighs about 320 g. The skin appears dark red and begins to develop vernix caseosa. The entire body is covered with fine lanugo, and some hair growth is evident. The fetus begins to show swallowing and urinary functions. From this point onward, fetal weight increases linearly. Fetal movements become more pronounced, with active movements occurring 10–30% of the time.

- End of 24 weeks: The fetus is about 30 cm in overall length, 21 cm in crown-rump length, and weighs approximately 630 g. All organs are developed, and subcutaneous fat begins to accumulate, though the skin remains wrinkled due to insufficient fat. Eyebrows and eyelashes appear. Though small bronchi and alveoli have formed, primitive alveoli are scarce in fetuses younger than 22 weeks. Fetuses born at this stage may breathe but have an extremely low chance of survival.

- End of 28 weeks: The fetus measures about 35 cm in overall length, 25 cm in crown-rump length, and weighs around 1,000 g. Subcutaneous fat remains minimal. The skin appears pink and is covered with vernix caseosa. The pupillary membranes have disappeared, and the eyes are partially open. The limbs exhibit good movement, and respiratory movements are evident. Although survival becomes possible if born, preterm complications remain high, especially respiratory distress syndrome.

- End of 32 weeks: The fetus measures about 40 cm in overall length, 28 cm in crown-rump length, and weighs around 1,700 g. The skin is still dark red and wrinkled. The survival rate improves significantly.

- End of 36 weeks: The fetus measures about 45 cm in overall length, 32 cm in crown-rump length, and weighs approximately 2,500 g. Subcutaneous fat becomes more abundant, giving the body a fuller appearance. Facial wrinkles disappear, and nails reach the fingertips or toes. The fetus is capable of crying and sucking after birth, with strong survival potential as it approaches full term.

- End of 40 weeks: The fetus is about 50 cm in overall length, 36 cm in crown-rump length, and weighs approximately 3,400 g. The fetus is fully developed, with pink skin and abundant subcutaneous fat. The soles of the feet display creases. Testicles have descended into the scrotum in males, while the labia majora and minora in females are well developed. After birth, the cry is loud, the sucking ability is strong, and survival capabilities are optimal.

Physiological Characteristics of the Fetus

Circulatory System

Nutrients needed by the fetus are supplied by the mother, and metabolic waste products are transported and excreted via the placenta. Due to the high pulmonary vascular resistance and the presence of placental and umbilical circulation, the fetal cardiovascular system functions differently compared to the newborn stage.

Features of Fetal Blood Circulation

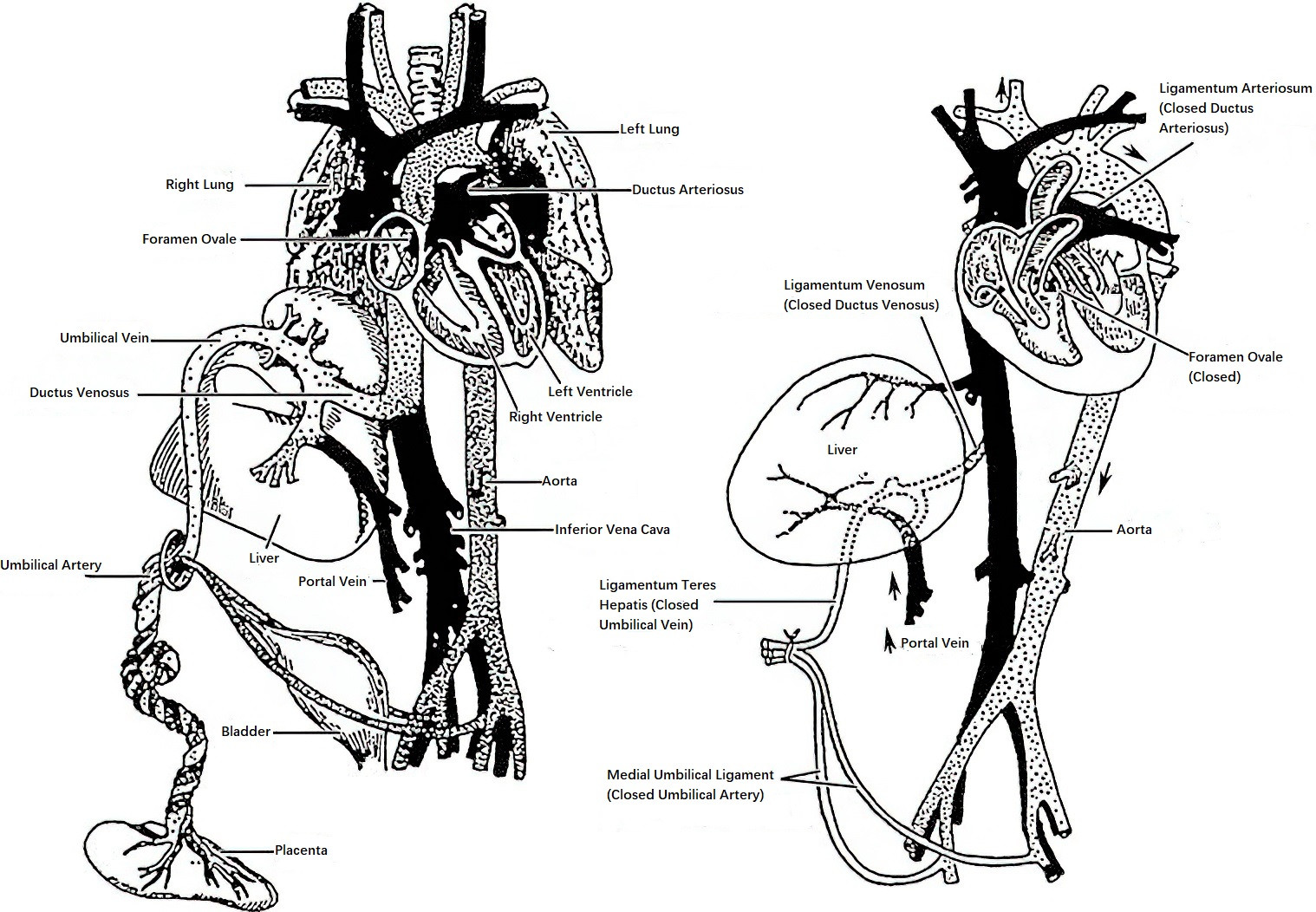

Blood from the placenta enters the fetus through three pathways: (1) directly into the liver, (2) into the liver after merging with the portal vein, with both pathways entering the inferior vena cava via the hepatic vein, and (3) directly into the inferior vena cava through the ductus venosus. The ductus venosus is a short vessel unique to the fetal period that connects the umbilical vein to the proximal inferior vena cava, serving as a crucial channel for fetal blood circulation. After birth, the ductus venosus obliterates and becomes the ligamentum venosum. The blood in the inferior vena cava is mixed, containing oxygen-rich blood from the umbilical vein and oxygen-depleted blood from the lower half of the fetus.

The foramen ovale, located between the right and left atria, enables the majority of the blood entering the right atrium from the inferior vena cava to flow directly into the left atrium. Blood entering the right atrium from the superior vena cava flows into the right ventricle and then into the pulmonary artery.

Due to the high resistance of the pulmonary circulation, most pulmonary arterial blood bypasses the lungs and enters the aorta through the ductus arteriosus, with a smaller portion of blood entering the left atrium via the pulmonary veins. Blood in the left atrium flows to the left ventricle, is pumped into the aorta, and eventually reaches the entire body. Afterward, blood travels via the umbilical arteries into the placenta to exchange gases and nutrients with maternal blood.

Fetal blood circulation lacks purely oxygenated arterial blood, as blood throughout the body is a mixture of oxygenated and deoxygenated blood. Blood that supplies the liver, heart, head, and upper extremities has relatively higher oxygen content and nutrient levels to meet the metabolic and growth needs of the fetus. Blood supplied to the lungs and lower half of the body has relatively lower oxygen and nutrient levels.

Features of Newborn Blood Circulation

After birth, placental and umbilical circulation cease, and the lungs begin to function for respiration, leading to decreased pulmonary vascular resistance and gradual changes in neonatal blood circulation:

- The umbilical vein becomes the ligamentum teres hepatis, and its terminal ductus venosus obliterates to form the ligamentum venosum.

- The umbilical arteries close, forming the medial umbilical ligaments along with the obliterated hypogastric arteries.

- The ductus arteriosus located between the pulmonary artery and the aortic arch fully closes within 2–3 months postnatally to become the ligamentum arteriosum.

- Increasing left atrial pressure induces the closure of the foramen ovale, which is typically completely sealed by 6 months after birth.

Figure 1 Blood circulation of the placenta, fetus, and neonate

Hematological System

Erythropoiesis

By the 5th week of gestation, hematopoiesis begins in the yolk sac, and later the liver, bone marrow, and spleen gradually acquire hematopoietic functions. At term, 90% of red blood cells are produced in the bone marrow. By the 32nd week of gestation, significant amounts of erythropoietin are produced, leading to an increased red blood cell count in newborns born after 32 weeks of gestation, which is approximately 6.0×1012/L. Fetal red blood cells have a short lifespan of about 90 days and require continuous production.

Hemoglobin Production

During the first half of gestation, hemoglobin is mostly fetal hemoglobin. In the final 4 to 6 weeks of gestation, the amount of adult hemoglobin increases, and by the time of delivery, fetal hemoglobin only accounts for about 25%.

Leukopoiesis

Granulocytes appear in the fetal circulation after 8 weeks of gestation. By the 12th week of gestation, lymphocytes are produced by the thymus and spleen, serving as the primary source of antibodies in the body. At term, white blood cell counts can reach (15–20)×109/L.

Respiratory System

During the fetal period, the placenta substitutes for lung function, allowing maternal-fetal blood to exchange gases within the placenta. Prior to birth, the fetus develops respiratory structures, including the airways (from the trachea to the alveoli), pulmonary circulation, and respiratory muscles. Fetal chest wall movements can be observed via ultrasound as early as 11 weeks of gestation, and by 16 weeks, respiratory-like movements occur, facilitating the flow of amniotic fluid in and out of the airways. After birth, alveoli expand, enabling functional respiration. Immature lungs at birth can lead to respiratory distress syndrome, affecting neonatal survival. Fetal lung maturation encompasses both structural and functional development, with the latter involving the production of surfactant in the lamellar bodies of type II alveolar cells. Surfactant components include lecithin and phosphatidylglycerol, which reduce alveolar surface tension and aid alveolar expansion. The degree of lung maturity can be assessed by measuring lecithin and phosphatidylglycerol levels in amniotic fluid. Glucocorticoids promote surfactant production.

Nervous System

The fetal brain grows and develops progressively during gestation. During the embryonic period, the spinal cord fills the vertebral canal, though its growth slows subsequently. Starting at six months of gestation, myelination of nerve roots in the brainstem and spinal cord begins, although most myelination occurs within the first year after birth. By mid-gestation, the inner ear, outer ear, and middle ear are formed, and by 24 to 26 weeks of gestation, the fetus can perceive sounds. At 28 weeks, the fetal eyes begin to respond to light, although visual perception of shapes and colors develops gradually after birth.

Digestive System

Gastrointestinal Tract

Between 10 and 16 weeks of gestation, the gastrointestinal system is functionally established. The fetus is capable of swallowing amniotic fluid and absorbing water, amino acids, glucose, and other soluble nutrients.

Liver

The fetal liver lacks many enzymes and is unable to conjugate the large amounts of free bilirubin produced by the breakdown of red blood cells. Bilirubin is excreted into the small intestine via the bile ducts, where it is oxidized into biliverdin. The degradation products of biliverdin give meconium its dark green coloration.

Urinary System

By 11 to 14 weeks of gestation, fetal kidneys have developed the ability to produce urine, and by 14 weeks, urine is present in the fetal bladder. The fetus contributes to amniotic fluid circulation through urination.

Endocrine System

Thyroid development begins at the 6th week of gestation, and by 10 to 12 weeks, the thyroid can synthesize thyroid hormones. Thyroid hormones are crucial for the normal development of fetal tissues and organs, especially the brain. From the 12th week of gestation, iodine uptake by the fetal thyroid surpasses that of the maternal thyroid, necessitating cautious iodine supplementation during pregnancy. The fetal adrenal glands are well-developed, with the adrenal cortex primarily consisting of the fetal zone, capable of producing large amounts of steroid hormones. Together with the fetal liver, placenta, and maternal body, the fetus participates in the synthesis of estriol. By 12 weeks of gestation, the fetal pancreas begins secreting insulin.

Reproductive System and Gonadal Differentiation and Development

The details can be seen in “Development of Female Reproductive Organs.”